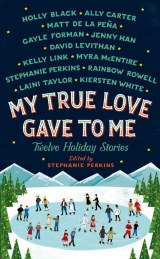

Текст книги "My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories"

Автор книги: Stephanie Perkins

Жанр:

Рассказ

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

It is the custom on the Isle of Feathers for young men to leave small gifts for their sweethearts on each of the twenty-four days of Advent.

Having no sweetheart and desiring none, Neve Ellaquin woke on the first of December without expectations. Well, that’s not strictly true. She expected rain, because rain was as sure a feature of a December day as hungry foxes. And she expected quiet, because that’s what she’d had in abundance since the twins died together in late summer, leaving her alone in this benighted place. She expected, roundly, a heaping spoonful of the same dolorous drear that November had served up, only colder. That was the way of things as Neve knew them: there were no good surprises, only bad. In the evening, when she took her single, cherished book out of the chest to read by the fire, it would hold the same stories it always had, and so would her days, until they ended.

Her feet fell off the bed’s edge like lead weights, and the morning’s first sitting-up breath was a sigh.

“It’s too early in the day for sighs,” she said aloud. She talked to herself all the time now; she used her voice to slice the heavy air into strips so it wouldn’t smother her. “If I spend all my disappointment before breakfast, what will I go on for the rest of the day?” And she smiled at herself for being such a sour thing. She thought of Dame Somnolence at the factory, whose advice to the girls was to “live bitter, so the crows will have no taste for you when you’re dead.”

“And why should I deprive them of nourishment?” Neve had countered, because before this summer she’d still had it in her to be saucy. “Don’t they deserve a treat, too?”

“And you want to be that treat?”

“Why not?” Neve had asked. “What do I care for my carcass once I’m done with it?” And ever since, Dame Somnolence had called her Crow Food instead of her name. Never mind that it no longer suited her. Neve thought she had to be the bitterest snack of flesh on the island these days—especially now, with Christmas coming and the twins gone and gone.

The twins. Ivan and Jathry. With Neve, they’d been part of the batch of kids brought here twelve years back: plague orphans from the Failed Colony, bought cheap and worked hard, the boys in the field, the girls in the factory, their food thin and their beds thinner, out in the wind-taunted sheds behind Graveyard Farm. The light at the end of the tunnel for the lot of them: they were free once they reached Age. “Age,” they all called it, that simple, like it was the only one that mattered. Age was eighteen, and as for “free,” what does free mean to work orphans turned loose with their pockets full of air, on an island in the middle of the blasted great Gliding? Ship’s passage cost more than their lives were worth, and some boys chose to pay that price, just to get away. Signing themselves over to a crew on a contract they’d be lucky to pay off before they saw fifty—and what sailor on the Gliding ever saw fifty?

So most of the boys stayed on the Isle of Feathers, and all the girls did, because though a ship would have been happy to take them, it was on a different kind of contract, and no girl—none—could ever hate the island enough to make that choice. So “freedom” for a girl meant one thing only: freedom to marry, and so that’s what they did. The lucky ones caught the eye of a boy from a First Settlement family—or perhaps not a boy but a man (there being no shortage of widowers on the Isle of Feathers)—and the less lucky, one of the late-come tradesmen who’d hung up shingles in the harbor town. The least lucky of all? One of Neve’s own caste, a “plague boy” with nothing to his name but a pair of work-rough hands.

The First Settlement families owned all the good land, so those girls got real houses whose walls didn’t moan and sway, and gardens that grabbed the best sun, and maybe even a ribbon of clear water slipping across their plot, as aglint with green-gold fish as the mosaics of the church floor. And some of the tradesmen did well enough and some didn’t, so those girls might end up in one of the skinny, gabled row houses on the pitched streets of the harbor town, or else in a flat above a shop, or the cellar beneath a pub, or some place like that. And the orphans’ brides? Well, there were parcels of land to be had for free in Fog Cup—the valley in the middle of the isle so named because it was little more than a cup for fog—and no one would call it good land, but most years it was enough to make a life on. Most years. If you didn’t have too many mouths to feed, and you didn’t mind the damp.

I ask you, who doesn’t mind the damp?

Still, that had been Neve’s plan: Fog Cup, with the twins. They’d thought, once upon a time, that they’d be married all three together. Why not? Back then, to them, marriage just looked like grownups living in their own house and making up their own rules, and what else had they wanted since setting foot off the stinking ship that brought them here? Later on, though, Bill Childbreaker told them—in more detail than was necessary or decent—what went on betwixt husbands and wives, and they’d stared at each other, red-faced, their innocence dissolving like scoops of beached sea foam.

Not marriage, then.

If Ivan and Jathry had been one boy instead of two, then Neve guessed she would have married him, but choosing between them was never an option. When they walked down a road, Neve walked in the middle. That’s just how it was. And when they grew up enough that the carnal secrets of marriage no longer shocked them, well. If either Ivan or Jathry felt husbandly toward her, Neve never knew it, and she had no wifely stirrings herself. They were strong boys with good faces, and they’d been part of her heart since home—true home, long lost—but it wasn’t like that between them. There were no glimmering moments where their looks hooked on to each other and grew hot, and no catching sight of one of the boys in a ray of sun and thinking, I wonder what his skin tastes like. There was never a hint of a blush, nary a tingle, never any of the things the other girls talked of at the factory, breathless and blushing and purring with longing.

Oh, and today would be rife with blushing and purring, Neve knew, and with crowing and gloating from girls who got the best gifts, and weeping and sulking from those who got none, or worse: a gift from the wrong fellow, some drunk or lecher, or maybe that shameless nose-picker “Three-Knuckle” Mickle-Jon Herring, perish the thought.

And then there was Reverend Spear, a category of threat all his own.

A cold weight settled in Neve at the thought of the island’s tall, handsome preacher. He was fire and brimstone, a man possessed, and his sermons were like travelogues of Hell. This lake of fire, this pit of the damned, these gnawing serpents, and all the ingenious implements in the hands of demons who would spend an eternity peeling you like fruit and slowly devouring you, only then to begin afresh, and savor you for another thousand years. If children didn’t wake screaming on Sabbath nights, he considered the sermon a failure and the next week’s was worse. Once, when a farm boy was caught with a potato in his pocket, the reverend convinced Bill Childbreaker to lash him as an example, and when a clatch of girls were found swimming by moonlight at Song Beach—in their petticoats, not even their birthday suits!—he had them shut in their houses for the whole rest of the summer, with signs on all their doors that said INDECENCY IS AN AFFRONT TO GOD.

He’d lost his third wife this year—to the same fever that took Ivan and Jathry—and he made it no secret that he’d be choosing another for Advent. Why pay a charwoman for work a wife would do for free? And besides, wives were more than just unpaid charwomen, weren’t they? Neve saw him looking the girls over in church like they were his own box of chocolates—eeny meeny, who am I in the mood for next?—and she’d felt his gimlet eye settle on herself a few too many times for comfort.

His pupils always looked tiny to her, like painted-on dots.

She told herself she didn’t have to worry. Spear liked to claim that pretty girls made troublesome wives, he’d learned it from experience, and had even said once, for all to hear, “Beauty is free to the eye to enjoy, and the bedroom is dark, after all. But just try pretending your dinner unburned, or your house clean and your children tended.”

In essence, wasn’t their good man of God saying to close your eyes and picture some other man’s wife while you grunt atop the poor homely slave who’s your own?

Neve hated him, and she was honestly sorry for whoever got his gift this morning, but she didn’t think it would be herself. She knew she was pretty, and if she’d never had cause to be grateful for it before, here was proof that there’s a first time for everything. Maybe she’d be the one he pictured in the dark, and that was a notion vile enough to choke on, but she wouldn’t be the one he courted.

She just wouldn’t.

She dressed herself. The shed was frigid; dressing quick was an art learned early. Washing quick was harder; you had to really care to even bother. Neve cared, Lord knows why. At least her basin wasn’t skimmed with ice yet. That would come by January and last through April. Still, this water was kissing cousins to ice, and she was shaking with chill when she yanked on her stockings and slip, her dress and kirtle, her many-pocketed apron, her old, dull boots. Even numb-fingered, it was the work of a minute to bind up her hair, honeysuckle bright, and cover it with a kerchief the color of mud.

And then what? She glanced at the door. On a normal morning, she’d tromp out to the henhouse first thing—not that her sad hen Potpie had been laying of late, but she still checked as a matter of course—but she found herself hesitating and knew well enough why. She was wondering at the state of her porch.

Was it as empty as she’d left it the night before?

“Please God,” she whispered, and right away it struck her as the wrong plea. If there was a god, then Neve’s whole life was a crime He had committed against her, and she dared attract no more of his attention.

She looked to the milking stool that served her for a bed stand and drew some strength from what lay upon it.

A dead flower.

How many girls on the Isle of Feathers had a dead flower ready this morning? And then, how many knew there was no courtship so bad that she could afford to reject it?

That was how it worked: You woke on the first of December to find—or not find—a token of affection on the porch. A paper cone of sweets or a whittled bird or a posey, maybe. To reject the suit, you left a dead flower in the spot for the fellow to find the next night. Acceptance was tacit. You did nothing, just rose each morning to see what your future husband had left for you, twenty-four days in a row until the Christmas Eve gather in Scarman’s Hall. That’s where the couples came together under a lacework of paper snowflakes and frosted lamps and sealed their fates with a dance. You set your hand in his and that was it: contract sealed with the clamminess of a girl’s despairing sweat.

How romantic.

Neve had no expectations, but she had a dead flower ready, just in case. It was a thorn lily, left over from summer.

From before the fever.

She lifted it gently. It was crisp as paper, light as nothing. When this flower was alive, Ivan and Jathry were too. Neve had picked it on a Sunday when the three of them climbed up to Fog Cup to inspect the land the boys were going to take. They’d been closing in on Age, though Neve still had nine months to go; the three of them were the youngest and last of the plague orphans, she herself the very youngest, the very last. She’d always known she’d be alone here at the Graveyard sheds for a time before they set her “free” too, but that would have been a different kind of alone: just waiting, just biding time before she could claim her own plot up by the boys’.

She was still going to take the plot, even if it didn’t make sense anymore. The boys had been the farmers. What was she good for? Needlework. That was what they did at the factory. They embroidered lace tablecloths for ships to carry to rich folk on every shore of the Gliding, and Neve was better than passing fair; she was better than good. She was an artist. Even Dame Somnolence said so, calling her “Crow Food” with at least a hint of respect. But a great lot of good were needle and thread when it came to building a house in a drear damp valley and tilling stony soil without a mule, and all the other things she’d have to do to live.

If you could call it living.

Neve was scared clear down to a deep place inside where a part of herself was caged like a creature, mute and huddled and numb. She’d been numb since the heat of August mingled with the heat of fevers, but even so she knew that as long as she kept breathing, life would keep coming at her—like the swarms of beetles when you’re harried enough to take the shortcut through Nasty Gully in springtime. They come flying in your face, loud and buzzing, and get tangled in your hair and in your skirts. They even push their way into your mouth.

Life would do the same. Neve couldn’t pretend otherwise. In truth, she dreaded the lonely penury of Fog Cup almost as much as she dreaded the breathing weight of a man she couldn’t love, and if there was a token on her porch, she knew in her secret heart she’d be a fool not to consider it. But she didn’t want to consider it. She wanted to be free, and if she could never be free, at least she wanted to be brave—brave enough not to sell herself, no matter what the payment, or the cost of refusing.

Holding the dead flower, she squared her shoulders. Brave, she thought, and went to the door. Brave, she thought as she opened it.

But brave she was not when she saw what was sitting there, incongruously fine against the buckled boards of her rotting, charity-shed porch.

It was a Bible bound in red leather and stenciled all over in gold.

Only one man would leave such a gift. One man had done so, in fact, three times before—three times for three wives whose graves now stood in a row, and with plenty of space at the end for that row to grow and keep adding to its collection. Who’s next? called the cemetery earth. Why, the last of the orphans, the artist, the girl with the honeysuckle hair.

Neve clutched her frail lily and stared at the Bible whose pages had been thumbed by dead women. So Spear wanted her after all. In that place inside where her fear was caged like a creature, something stirred and rose, and she spoke a new plea without pausing to think. Not to God, Spear’s coconspirator. God was a newcomer here, carried over on the same stinking ships as the orphans and livestock.

There were older powers in the world than Him.

“Please, Wisha,” whispered Neve, and she felt the forbidden word part the air like the wings of a bird and go forth from her. Wisha. Dreamer, it meant in the old tongue. It was an execration to speak it, but it didn’t feel like one. It felt like power, like the birth of a small wind. Neve imagined it skirring its way into the world, new-alive and wild with her own desperate thrum, kicking up eddies of air that might grow, some day, into thunderheads and sink a fleet of ships half a world away. But what good was that to her? Much nearer and in that instant, at the threshold of her freezing shed while rain hissed at the roof and the heavy air pressed down, dense with its absence of voices, she saw something happen. The red leather cover of that unwanted Bible flapped open in a violent gust. Pages riffled and came loose, rising into the air like a flock of something freed. First the pages, then the rest.

All of it rising, swirling, gone.

“Please,” Neve whispered in its wake. “I am alone.” If her fear were a creature, this would be its bones. Alone. Alone. This was the fear that wore all other fears like skin. Her next words sounded like a bastard version of the catechisms she’d been forced to recite for twelve long years, but they felt truer. Cleaner. “To your protection I commend myself, soul of this land. Wisha.”

And there came a change in the atmosphere, a … tautening, as though the land itself were baring its teeth. Neve felt it.

She welcomed it.

Wisha.

* * *

When the first ship made landfall here two hundred years ago, its crew found no sign of folk—nary a chopped tree nor a circle of stones to hint that men had ever walked here. The land was fertile and primal and deepest green, untilled, ungroomed, and as wild as the Gliding itself. But for one thing.

The black hill.

It was perfectly symmetrical, wider than it was tall, and taller by ten than a haystack. It looked, at a distance, like a miniature volcano, and its true curiosity was its covering. It was dressed all over in strange plumage: feathers, oil-black and overlapping as neat as fish scales. Far too large for crows, each plume was as long as a man’s arm, and some said that only a bird as big as a man could have plumes so very long. Of course, no such bird existed, and because of that—and because of what was inside the hill, under the plumes—the sailors set fire to it.

And died.

It was the smoke, said the survivors. Oil-black as the feathers themselves, it … writhed.

It hunted.

The sailors who were upwind of the fire saw what it did, and ran for their ship.

Some of them made it.

It was a full twenty years before another ship came, and this one came ready, armed with God and shovels, and they didn’t burn the feathers this time but buried them, and they built a church on the hill and filled it with saints’ bones and imprecations against evil. They divvied the dark green land among themselves, taming the place with prayer as they shaped it with labor, and the long black feathers became a thing of myth. Children might play at “quicksmoke,” chasing each other with burning crow feathers and acting out gruesome deaths, but the true accursed plumes had not been seen for near two centuries.

No one was afraid anymore, not really.

On this first morning of Advent, though, as the isle folk stirred awake and girls darted barefoot onto porches to find what was left for them, the isle stirred too. Only a little, and only Neve felt it. The old hill—long since defeathered—was a lonesome spot, far from any farms, and its bare stone church saw visitors but rarely. It would be Christmas day before the damage was discovered—the floor caved in, a pocket of deep, dark air opened underneath—and by then the events of this Advent would be done and known.

By then, everyone would know that the Dreamer had awakened.

* * *

In the harbor town, the folk were decorating. Swags of limp tinsel wove down both sides of the high street, and dames were up ladders, skirts tucked tween their knees as they stretched to hang up fishing floats and old baubles of scratched mirror glass. Every door wore a wreath and red ribbon, and hunchback Scoot Finster was making his way from shop to shop with stencils and a bucket, dabbing scenes onto glass with his own recipe of fake snow.

The harbor folk loved their Christmas, and it was no secret that they loved it like pagans. They wanted to dance and drink, put on their oversize saints’ masks and caper about frightening babies. Unlike the First Settlers, who were of Charis stock and came into the world, so they said, with their hands folded in prayer, these latecomers were mostly descended from Jhessians, those sharp-eyed folk of old tongue and older gods, and they wore their civility as light as summer shawls. But life was hard here and the myths were dark, and the Church kept them proper, most days.

“Mornin’, maidy,” Scoot called to Neve as she passed him on her way to the factory. “Find ought on your porch this drizzle-blasted morning?”

His smile seemed genuine, so Neve guessed he didn’t know. The fishwife behind him, though, sucked in one cheek to chew and looked caught between pity and envy, and that’s how Neve knew the word was out.

She didn’t answer. She couldn’t very well lie and say no, but neither could she bring herself to admit it, at least not without making clear how she felt about it, which would simply not do. Girls were supposed to be happy that someone wanted them, as though they were kittens in a basket, and any left by day’s end would be drowned in the pond.

Scoot misread her silence. “Well, maybe the ghosts of your boys haunted off all your suitors,” he said kindly. “It’s the only explanation, a sip of honey like you.”

Neve murmured some response, though she couldn’t have afterward said what. She cast down her eyes and kept going, glancing back at the turning of the lane to see the fishwife talking in the hunchback’s ear, and him looking rueful after her, like she was a kitten already sinking beneath the water.

Was she?

No.

Because she was going to refuse.

“You’re going to what?” demanded Keillegh Baker when Neve told her.

It was midmorning, and they were at their hoops in the longroom, needles busy. All down the row girls blushed and purred and crowed and gloated and wept and sulked, just as Neve had known they would. Irene had a length of lace from her sweetheart, Camilla a comb from hers. May’s too-straight back told her tale of woe, while Daisy Darrow had gifts from three boys, and the delicious drama of a tussle on her porch, too, when they bumped into each other at midnight, all surly fists and mayhem.

“I thought Caleb would kill Harry,” said Daisy, eyes shining with the thrill of it. “But then Davis broke a pot over his head. Oh, Mam was mad. It was her strawberry pot from Cayn.”

Neve did not join in, but only whispered her news to Keillegh, the baker’s daughter, who was the closest she had to a friend anymore, and not quite a friend at that. The thing about having friends who are as close as blood, as true as your own heart—as the twins had been to her—is you don’t bother much with other people. And if you’ve the misfortune to get left behind, well, you’ve made yourself a lonely nest to sit in.

“I’m going to refuse him,” Neve repeated.

Keillegh was shocked, and Neve in turn was shocked by her shock. “Do you really think I could say yes?” she asked, incredulous. “To him?”

“Yes, I think you could say yes! What else will you do? You’re not still thinking of killing yourself at Fog Cup.”

“Not killing myself, no.”

“Not outright maybe. Just a slow death by mildew, if you don’t starve first. Ilona Blackstripe lost the rest of her toes, did you know that? And have you ever seen sicklier babies?”

“Well, I won’t be having babies, so it’s not my main worry.”

“No babies.” Keillegh shook her head, fingering the little silver chain that was her gift from her own boy. “I’ll never understand you, Neve. It’s like you’re another species. You had those two strapping boys out there and you never even kept warm with them, and you don’t want babies either? What do you want, may I ask?”

What did Neve want? Oh, wings and a hatful of jewels, why not? Her own ship, with sails of spider silk. Her own country, with a castle in it and horses to ride and beehives in the trees, dripping honey. What use was wanting when a full belly was as remote as a hatful of jewels? And she did want babies, truth be told, but in the same way as she wanted wings: in a fairy-tale version of life, where they wouldn’t look like those poor Blackstripe sicklings, and she wouldn’t be digging tiny graves every couple of years and pretending life went on.

And what about love? Did she want that, too? It seemed an even wilder fairy wish than wings. “Nothing I can have,” she replied, before the sparkle of senseless wanting could grow too bright.

Keillegh was blunt. “So take Spear and count your blessings. He may be a misery of a man, but his house is warm, and I happen to know he eats meat every week.”

Meat every week. As though Neve would sell herself for that! The rumble of her tummy just then was happenstance—a result of forgetting breakfast in all her nerves that morning, not to mention that her hen had dried up, poor Potpie, destined soon to fulfill the promise of her name.

The reverend, Neve knew, had a dozen hens and a strutting rooster to rule them.

The reverend had a cow.

Butter, thought Neve. Cheese. “That’s all lovely,” she said, settling her grumblesome tummy with a firm press of her palm. “But there is the matter of that row of graves. How many wives should a man get to put in the ground before someone tells him to get a new hobby?”

“So suppose you put him in the ground.”

“Keillegh!”

“What? I don’t mean by murdering him. Only outlasting him. It has to be easier than Fog Cup.”

Maybe so. Easier didn’t mean better, though. Some kinds of misery make you hate the world, but some kinds make you hate yourself, and—butter and cheese notwithstanding—Neve had no question that Spear was the latter.

But what if … what if … there was some other future lying up ahead for her—one without any misery in it at all—and even now it was trailing its way backward in time to meet her, and take her hand, and show her how to find it? It was funny. In life as perpetrated against Neve, there were only bad surprises, never good, but as the day wore on, she had a fancy that the queer small wind of the morning—kidnapper of Bibles—was circling round to check on her. Sure she was imagining it, but it didn’t feel like the usual longroom drafts. Those were errant shivers, chaotic, like little boys darting up to slip an icicle down your back.

This circling gust, this curious breeze … it wasn’t even cold.

* * *

The Dreamer could not have said how long he’d slept. He opened his eyes from dream to darkness, and to stillness—stillness like death, but he was not dead. The air around him was, and the earth that wrapped around that was, too, and something was wrong. He should have felt the pulse of life in it, in soil and roots, and seen the memories pulled down through grass and seeping water and burrowing beast. It should have been a symphony of whispers in his chamber, echoing and glorious with life. But all was silent.

Except for the call.

The language was strange to him; the words were just sounds, but they pierced him with such an urgency that he sat up on his catafalque—too quickly. Head spinning, he slid to his knees, and he knew a moment of panic so profound that his shock painted the darkness white. Behind his eyelids, inside his head: trembling, blinding white.

Something was wrong.

He had slept too long. On his knees in the dead dark, he knew—he knew—that the world was dead and he had failed it. Above him, around him, the veins of the earth had ceased to pulse. If he emerged he would find a vast waste, the gray dead hull of a dried-up world.

His heart that had beat so slow for so long: now quickened. His lungs that had lain airless for time indeterminate now wanted to gasp. Asleep, the Dreamer could abide inside this hill of earth. Awake, he could not.

But he dreaded what he would find if he emerged. Failure and death and ending. He felt it. It oppressed him with a heaviness he had never known.

In the end, it was the call that gave him courage. It had pierced him awake, and now it drew him up. He didn’t know the language, but this was a plea deeper than words, and his soul strained to answer it. Summoning all his strength, he burst upward. The hill should have opened for him like a flower, but it resisted. Something weighed on it. On him. He couldn’t breathe. With a savage effort, he broke through.

And discovered that the world was not dead. He stumbled out into it, drunk with gratitude, blinded by even the dim winter sun, and fell to his knees in the grass. He sank long fingers in and felt the pulse and drank the memories, so many, so deep—how long? As his senses grew accustomed to the outside world, he saw and smelled many things that had not been here before.

The stone building that squatted on his hill, for one.

People, for another. When he had made ready his place of rest, humans had dwelt along the green coasts of southern lands, but these islands had been wild, the province of petrels and seals. Now he scented smoke on the wind, the warm odor of manure, the sharper reek of cesspits. The wildness had been broken.

Had he? What had they done to him, these folk?

They had stolen his feathers and smothered him under some blunt sorcery of their own. They had broken, for a time—how long?—his connection with the earth.

But …

He turned in a new direction. There stood a fringe of trees so green they looked black in the soft light, but beyond them, rolling away, where once had been forest, now all was plucked, carved into corners, scraped into furrows. Wisps of hearth smoke rose at intervals, and the Dreamer sensed the coursing of many lives. But one most brightly.

The one who had awakened him.

* * *

Two things, at the end of the day, in case Neve hadn’t made up her mind.

First, Dame Somnolence held her back when the other girls left. “Here,” she said, thrusting a flower at Neve. “In case you don’t already have one.”

Fumbling to take it, Neve saw that it was dead. She looked up, right in the old woman’s globe-round eyes—too large, too unveiled, the lids never quite seeming up to their job.

“You think I should refuse him, then,” she said.

Dame Somnolence gave a snort. “I think he’s due a nice long tour of that Hell he loves to preach about, that’s what I think. Or maybe he’s been there already, to know so much about it. Take this, Crow Food. Put it on your porch. There’s not a bird in the world that would eat his brides. You think you know bitter now? You’ll taste like ash before he drops you in a grave.”

Neve already had a dead flower. She tried to return the dame’s, but she wouldn’t have it. “Take it,” she said. “I killed it special for whoever got his gift.”

And so Neve did take it, and she was glad to have it when she found the man himself waiting for her just outside of town.

This was the second thing.

He smiled when he saw her coming. His teeth were so white and square they looked chiseled out of walrus ivory. “Good evening, Neve,” he said. This was a liberty. He ought to have called her Miss Ellaquin.