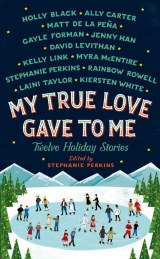

Текст книги "My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories"

Автор книги: Stephanie Perkins

Жанр:

Рассказ

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“I’m a vegetarian,” she said, but she’d stopped shaking.

I smiled. “I’ll buy you a salad.”

Then I gave her a peck on the forehead and stepped into the light.

* * *

I’d behaved for thirty-one hours, shown restraint with Gracie, and had an intelligent conversation with her father. I’d found tablecloths to cover the legs of the waitresses-now-angels, persuaded Lee and Grant to put on wigs and robes (two of the Wise Men were stuck in traffic), and attached cotton balls to sawhorses to create sheep.

I’d wielded a glue gun to finish hemming Gracie’s costume—with no hit to my masculinity at all—and borrowed an eighth-grade gamer from the middle school choir to run lights. I’d untucked the robe from the back of an unaware shepherd’s pants, removed the Confederate caps from the horses-now-donkeys, and located Benadryl for a nervous stage mother.

Talk about your Christmas miracles. There was only one problem.

No Joseph.

“Did we make him mad?” I asked Gracie. We’d found the playbook, perfectly organized, but Shelby had disappeared. “Is this my fault, too?”

“No, he’s not that kind of guy.” She threw her hands up into the air. “We never dated, not even once. Something’s wrong.”

We didn’t have any extra bodies to stand in as Joseph. Gracie’s father was outside handling the tickets and the traffic, and … that would be gross, anyway. I couldn’t even pull an overgrown middle-schooler from the choir, because he was their only tenor.

I was at the end of my alternatives when Pastor Robinson reappeared. “We found Shelby,” he said. “Passed out under a pile of burlap. He’s running a high fever, and he’s delirious. Keeps talking about Democrats and New Jersey and kissing.”

“So we don’t have a Joseph.” Gracie kept her eyes on her father, but her hand moved to mine.

“No, we don’t.” He was very obviously not looking at me, either.

Oh, no.

“Come on.” I took a step back. “No way. No one in this town will buy me as Joseph. They’ll boo at the nativity. You can’t have people booing at the nativity. And I might be a troublemaker, but what I do is underhanded. Sneaky. I don’t like people looking at me. And people would have to look at me.” I was babbling, but the last thing I wanted to do was put on a robe and a fake beard and pretend to be the father of Jesus.

“It’s okay, Vaughn. You don’t have to do it.” Gracie squeezed my hand. “We have time to figure something out.”

“Ten minutes!” It was the eighth-grade gamer on the earpiece.

“We could use one of the Wise Men,” Gracie suggested. “Pull someone out of the crowd to take his place. All he has to do is stand there.”

Pastor Robinson nodded. “That could work. We might have to open the curtain a few minutes late—”

“I’ll do it.” Was that coming from me? It was. “I’ll be Joseph.”

“Son, you don’t have to. I promise,” Pastor Robinson said. He meant it, and not because he’d be ashamed for me to take the role. I could tell that he was thinking about me, my feelings. And he’d called me son. “Performing wasn’t a part of your deal.”

I looked from Gracie to her father, and all I saw on their faces was concern. Not judgment, not disappointment, not expectation. Nothing.

Just love.

“Directing the pageant wasn’t part of the deal, either,” I said.

“This is different,” Gracie said. “No one wants you to be uncomfortable—”

“I want to.” I held up my hand when Gracie started to argue. “No. I really want to.” I turned to her father. “The least I can do is put on a fake beard and stand up for what you believe in.”

Gracie was biting her lip. I might have seen tears in her eyes.

“Thank you,” Pastor Robinson said. And then he hugged me.

“Right.” I swallowed the lump in my throat. “So where’s the beard?”

* * *

Gracie and I were alone on the stage, waiting for the curtain to rise, just a young couple from Nazareth on our way to Bethlehem to be counted in the census. Minus a donkey, but some things couldn’t be helped. Gracie told me the donkey thing wasn’t in the Bible anyway.

I was sweaty and nervous, but Gracie was smiling from ear to ear. It made the whole thing worth it.

“I’d say good luck.” I fiddled with a glue strip and slapped on the mustache. “But it’s ‘break a leg,’ right?” My beard flipped over. “Crap.”

Gracie laughed and reached out to fix it. Or so I thought.

“There are other things you can do for luck.” She stood on her tiptoes, lifted her chin, and placed a kiss on my lips. It was soft and sweet.

My knees went weak. Like, so weak I had to lean on her. “That was a surprise. Don’t get me wrong, a welcome surprise. But still.”

“I’m sorry. Did I take it too far?” she asked softly.

“No,” I said. The curtain began to rise. “You took it exactly far enough.”

If you do a search for “US cities named Christmas” (which, get a life, weirdo), you’ll get five main results. Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan, and Mississippi each had someone who decided, “Hey, let’s name our city after Christmas, because then it’ll be Christmas all year round!”

If you ever stumble across one of their graves, you are obligated to spit on it, because honestly.

However, on the I-15, between the glittering cityscape of Barstow and the stunning metropolis of Baker, there’s a crumbling freeway exit that’s so small and depressing, even Google doesn’t know about it. And here, cradled in the bosom of the ugly brown desert, is my home: Christmas, California.

Technically, it’s not a city. It’s not even a town. It’s a “census-designated place.”

“Where are you from, Maria?” I’ll be asked someday, and I’ll be able to say with utter accuracy, “Just some place.”

Christmas is slipping into a pit of obsolescence. That pit would be the local boron mine, where fifty workers literally squeeze their living from rocks. Someday the boron will run out, and our census-designated place will finally be allowed to die.

As I sit in the passenger side of my mom’s boyfriend’s eighteen-year-old Chevy Nova, the December sunshine coldly brilliant, I pray that day comes soon. It’s a forty-five-minute drive from the nearest high school, which means I get an hour and a half of quality time with Rick every day.

Our script:

Maria enters the car. Rick removes a tape from the deck, then puts in one of two cassette tapes, Johnny Cash or Hank Williams.

“How was your day?” Rick asks.

“Fine,” Maria answers.

“Homework?”

“Doing it now.”

Repeat every day for the last three and a half years.

Today, as we pull off the highway and onto the bustling main strip (a car repair shop, a gas station, a series of slumping duplexes, and the Christmas Café), Rick breaks script.

“Paloma found a new cook.”

I narrow my eyes suspiciously at the dull brick exterior of the Christmas Café, which isn’t a café at all. It’s a diner. But the Christmas Diner isn’t alliterative, and saints forbid anything about the place not be ridiculous.

Ted, the last cook, died last week. He’d worked here since it was opened thirty years ago by Rick’s mom. Dottie lives in a retirement home in Florida. Even though my mom has been with Rick for eight years, Dottie still refers to her as “that nice Mexican.” That nice Mexican runs the diner—covers the ordering, keeps track of the accounting, forces her daughter to work for tips alone—basically does everything Dottie is too busy being retired to bother with. She also works full-time at the mine with Rick.

I keep trying to feel sad about Ted, but we barely knew each other, even after three years of working together. Still, it’ll be strange not having him there. He was more of a fixture than a person. Like if I walked in and the freezer was just … gone. Another reason I need to get out of here, before I become stuck like Ted, stuck like Rick, stuck like my mom. Everyone here is miserable, and we’re all just punching our time cards until we die.

Or, in my case, until May, when I graduate and leave Christmas forever.

* * *

Rick drops me off in front of the duplex, then heads straight for the late shift at the mine. They actually let me take the car when I turned sixteen, but I got in two accidents (both my fault), so it’s still cheaper for Rick to drive me than for them to insure me. Cheaper trumps all.

I unlock the door and enter the dim, chilly stairwell. My mom doesn’t believe in heating. It’s a belief strongly supported by Rick. During the winter, it’s colder inside than it is outside. I shrug into the jacket that I leave by the door, check the mail—always neatly divided into the Sanchez and the Miller piles—and climb upstairs to the kitchen. The fridge is plastered with so many years of my report cards, they’ve formed a sort of wallpaper. I push past the milk labeled “Rick,” the yogurt labeled “Rick,” the eggs labeled “Rick,” and find a small container of unlabeled leftover turkey. It has the flavor and consistency of cardboard. I scoop it into the trash, still hungry.

Usually our fridge is packed with castoffs from the diner, but with it out of commission since Ted died, actual food has been scarce. My mom hasn’t cooked a meal in years. Never thought I’d miss Ted “Moderately Edible” Dickson’s culinary stylings.

My mom used to cook. Before Christmas, we hopped around. Sometimes living with relatives, sometimes on our own. No matter how small our kitchen, though, she made it work. She’d spend hours putting together tamales, dancing and spinning stories in musical Spanish. She’s different in Spanish than she is in English. Warmer. Happier. Funnier. Mine.

English mom began when we came to Christmas. She got a job here as the site administrator—a fancy name for a secretary who has to do everything. We lived in a little trailer right at the mine site. Then she got a second job managing the diner, and she and Rick started dating. And it wasn’t just the two of us anymore. One of these days, she’ll show up with her own “Rick” label, right across her forehead.

Fridge possibilities exhausted, I head over to the diner to make sure our schedules haven’t changed and to get something to eat. There’s a dented minivan in the parking lot. Several car seats inside. Luggage strapped to the top. Bad news.

The door opens with a rusted jingle, and an animatronic Santa insults my moral virtue three times. Ho, ho, ho. A train track overhead circles the entire room, a dusty Polar Express forever stalled on the verge of reaching the North Pole. Every surface not reserved for eating is covered in holiday kitsch. Glittery Styrofoam snowflakes, empty boxes covered in sun-bleached wrapping, twinkle lights with one strand always blinking out of sync, stockings with hot-glue stains revealing where pom-poms used to be, and a stuffed deer head, red-bulb nose long dead and antlers strung with limp tinsel. As if that weren’t freak show enough, from the ledge above the kitchen door, a sinister elf gazes malevolently down, its head cocked at a horror-movie angle.

A year ago, I stuck a tiny knife in its hand. No one has noticed.

I look for the other waitress, Candy—she covers mornings and early afternoon, while I do late afternoon and evening. But she’s not here, and I was right about the minivan. The corner booth is a pending full-mop situation. A harried-looking woman wears a pair of sunglasses with only one lens. She’s bouncing a screaming infant on her lap. A toddler climbs on top of the table in spite of the mother’s cautions, while a middling-sized one whines and a bigger one pouts.

She sees me, a combination of hopelessness and annoyance warring on her tired face. “Good luck. We’ve been here five minutes with no sign of a waitress.”

I freeze. If I back out now, I can leave. I’m not scheduled to work.

The bell at the window rings. Ted was short, like me, so he never used the order window. We always had to go into the kitchen to get it. “Order up!” a cheery tenor calls.

The woman sees my reaction and narrows her eyes.

“I—uh—I work here.” You had to admit it, didn’t you, Maria. “Be right back with some menus.”

“Thanks.” Her voice is tight.

I approach the window to find a miniature box of Cheerios, three kids’ cups of chocolate milk, one large Coke, and a deep dish filled with—baked macaroni? I lean forward, breathing in, and … wow. I’m not huge on pasta, but this smells like comfort smothered in cheese. There’s a bread-crumb layer on top that’s baked a perfect golden brown. The whole thing is still steaming.

I get on my tiptoes, but my view into the kitchen is limited. “Hey? I work here? Who is this order for?”

“Table two,” the voice calls. I look out to double check. There’s no one else in the restaurant. Just the crazy family.

“She said no one has taken her order yet. Is Candy back there?”

“It’s for table two.”

Frowning, I walk the tray over. “Here’s your food.”

The woman huffs in exasperation, prying her hair out of the baby’s fist. “No, we haven’t even ordered. Can we—wait, what is that?”

I’m already swinging the tray away, but I pause mid-action. “I think it’s baked macaroni. Do you at least want the drinks? No charge.”

The woman pushes her glasses up on her head, finally noticing the missing lens. Her laugh surprises me. It rings through the room. “Well, that’s embarrassing. And shows you what kind of birthday I’m having. You know, it’s the oddest thing, but this macaroni looks and smells exactly like what my mom used to make us on our birthdays.”

“Gramma?” the oldest child asks, perking up.

The mom’s face softens. “Yeah.” She touches the edge of the pale yellow dish. “This even looks like one of her baking dishes. That’s so strange! You know what, we want this.”

“Yeah?” I ask, confused.

“Yes. If we could get some plates?”

“Of course!” I rush behind the counter and grab four plates and silverware sets. The mom is in the middle of telling some story about a birthday treasure hunt. Everyone has calmed down—the older ones have stopped whining, the baby is eating the Cheerios, and the toddler is satisfied with his chocolate milk. The mom looks about ten years younger than she did when I walked in here.

“Can I get you anything else?”

She gives me a happy shake of her head. “This is perfect, thanks.”

I retreat, relieved but puzzled. Why did the new cook make that? Maybe someone else was here? I push through the door to ask what’s going on. And then I’m grateful my mouth is already open, otherwise I couldn’t have covered my jaw-drop.

Because the new cook is not some paunched, sixty-something, chain-smoking deadbeat.

He’s tall, a ridiculous chef’s hat making him even taller. Lean, with shoulders slanting inward so he seems to take up less space than he really does. Thick, dark eyebrows. There’s a single line between them that should make him look like a worrier, but there’s something inherently pleasant about his face. Maybe it’s the way his nose has the slightest off-center curve, like it was broken into a sideways smile.

Oh, and he’s not old. Maybe twenty, tops.

Oh, and he’s not unattractive.

“Hi!” He looks up from something boiling on the range. And there—when he smiles, his whole face lights up. It’s like his other expressions are placeholders.

I realize I’m beaming back. I tame my own mouth so I don’t look like a total idiot. “Hey. So. You’re the new cook?” Oof, yes, ask the guy cooking if he’s the new cook.

“Yeah! Isn’t this place amazing?”

“There … was no sarcasm in that statement. I’m confused.”

He laughs. “I couldn’t believe my luck when they hired me.”

Maybe I don’t know him well enough to understand when he’s joking. Surely he’s not sincere. He removes the pot from the stove, wipes his hands dry, and then holds one out to me. “I’m Ben.”

“Maria.”

His hand is big, but not in a meaty sort of way. I let go before he does, self-conscious. I don’t know what I look like right now. I didn’t bother checking myself in a mirror before coming over, because again: this is not what I expected to find.

There must be something wrong with him. Like, seriously wrong. It’s the only explanation for why he would consider himself lucky for getting this job.

The front door jingles as Santa insults another customer. Ben returns to whatever he’s making—for no one, apparently—and I walk out and scan the restaurant. It’s still empty except for the family, who seem to be having a great time. After checking to make sure their drinks are filled, I go back to Ben. I lean as casually as I can manage against the counter, but the kitchen is weird now. No comforting sameness. Ben has transformed it into an unknown quantity.

“So, who ordered the macaroni?” I ask.

“Table two needed it.”

“Right. But she didn’t order it.”

He shrugs, as though he, too, is unaware of how this all worked out. But there’s a sly pull at one corner of his lips. “They like it, though.” It’s not a question.

“They’re thrilled. Have you looked at the menu? We don’t offer baked macaroni. Probably because Dottie couldn’t think of a way to make it Christmassy.” Her signature dish is the Rudolph’s Delight Salad—iceberg lettuce, ranch dressing, and one token cherry tomato.

He shrugs again, and this time both corners of his lips follow the upward movement. “First day. I’ll figure things out.”

“Maybe it’s better if you don’t. That looked way yummier than anything we make.” Since it looks like Candy isn’t here, I reluctantly grab my uniform from its peg. It’s a red polyester dress that never sits right, with a red-and-white-striped apron. We also have to wear sequined reindeer-antler headbands.

Year. Round.

The door to the women’s bathroom always sticks, so I shove it open with my shoulder. It nearly slams into Candy, who’s leaning over the sink.

“Oh, sorry! I thought the bathroom was empty.” I turn to go, when I realize her shoulders are shaking. “Candy? You okay?”

Her reflection is drained of color by the fluorescent lights. She has dark circles under her eyes, but that’s nothing new. At least they aren’t bruises this week. Two years ago, when she first moved in with her boyfriend, Jerry, she was bubbly and bright. We used to hang out sometimes after work, if Jerry was still on a shift at the mine. She wanted to be a hair stylist, someday open up her own salon. She even had plans to go to business school so she could run it. But little by little, she stopped talking about school. Jerry didn’t like it. Then she stopped talking about doing hair. Then she pretty much stopped talking at all. I see her every single day, but I miss her.

She holds up a white stick, expression blank. “I’m pregnant.”

I close the door behind me. “Congratulations?”

“I had to sneak out from my shift to buy the test. I’m sorry. I couldn’t go any other time, because then he’d know.”

Jerry always picks her up. I see him sometimes, on the front sidewalk, counting her tips. And on payday he holds out his hand for her check without even asking.

She leans over the sink. Her spine curves, her head droops. “How am I ever gonna get away now?”

* * *

I make Candy stay in the bathroom. It’s not like it’s busy. When the family leaves, I trudge toward their table, dreading the mess. Instead, I find everything neatly stacked, no spilled drinks, no overturned plates. And—gloriously, impossibly—a twenty-dollar tip.

I squeal so loudly that Ben sticks his head out of the window. “Everything okay?”

“Better than okay! Best tip I’ve ever gotten! Thank you, Benjamin!”

“You’re welcome. But Ben isn’t short for Benjamin.”

The door jingles, announcing my mom … and Rick? Rick always says, “Why would I pay for someone else to make my food?” as he boils a scoop of rice or beans or whatever else he got in the bargain bin.

“What are you doing here?” I ask.

My mom glances around. She works in the back and rarely visits the actual dining area. She never can get over the diner’s shock-and-awe decorating tactics. A penguin nativity, complete with little baby penguin Jesus, snags her attention. “Our shift was halted. Machine failure. We thought you’d be home. We wanted to make sure you were okay.”

“Candy’s … sick. So I’m covering.”

Rick’s hands are jammed in the pockets of his Wranglers. “Your homework done?”

“Yes.” My voice is flat.

He nods. It’s the same motion he makes every evening when he asks me the same question and gets the same answer. Usually it happens at home, though, when we all get in from our various shifts. Then I pass him the remote so he can watch old episodes of Bonanza. A few years ago, I went through a bout of insomnia, and without fail he’d be out on the couch. We’d sit there, silent hours passing, the boring black-and-white cowboy adventures filling in the space between us.

Okay, fine, there were a few good episodes. But still.

The order bell dings, and I frown. Ben has placed three to-go containers on the shelf. “No one ordered anything!” I shout. My mom looks disapproving, so I stomp over to the window. “Ben! No one is here. No one called in an order.”

He leans his head over. “Oh, right! Well, it’s embarrassing, but I messed up. Instead of throwing it out, I thought you could give it to your parents.” He says it’s embarrassing, but his expression is wrinkled with delight.

“Rick is not my dad.”

“Cool. Well. Ask if they want it.”

I glare. It’s harder than it should be, like his sweet, smiley face is contagious. “Quit making food before people order anything.”

“Right.” He grins even bigger and then straightens so I can’t see his face anymore.

I shove the containers at my mom and Rick. “I guess he messed up an order. Want some free food?”

Rick doesn’t even ask what it is. Free is the only part that matters. He turns toward the door. “Are we going, Paloma?”

My mom frowns. “Tell Ben to note what he’s using. We have an ordering system that doesn’t allow for waste.”

When they’re gone, I check the women’s bathroom and find Candy curled up asleep in the corner, an apron under her head. I hang an “Out of Order” sign and take the rest of her shift. As a small act of rebellion, I don’t change into my uniform. It has nothing to do with Ben.

Well. Maybe a little.

It’s busier than normal, a handful of locals sauntering in to check out the new chef. Ben doesn’t talk much—he smiles and waves out the window, too busy to come out. I stick my head through to find him pulling cookies out of the oven. The telltale scent of gingerbread hangs in the air like the promise of holiday cheer. He even has flour on his crooked smile of a nose. It’s adorable.

“You are a terrible cook,” I say.

He looks up, gentle features set in alarm. “Have there been complaints?”

“You haven’t followed any of the standard recipes. I’ve worked here long enough—I can tell.” The mashed potatoes are creamier. The fries are crispier. And his rolls are golden, buttery-topped miracles instead of the straight-from-the-bag variety we normally serve.

For a moment, he looks distressed. And then the agitation melts away as his eyebrows lift, disappearing beneath his mop of brown hair. He is the definition of merry. “But has anyone complained?”

I blow my bangs away from my eyes. “No. They’re just being nice because you’re new.”

That’s not true. The regulars like their familiar terrible food, and if anything is ever different, I get yelled at. They’re not nice.

Except … tonight, they are. Steve and Bernie, who always get a steak after their shifts and don’t say a word to anyone, are laughing and swapping stories at the counter. Lorna, who after my entire life of never ever stealing anything still follows me suspiciously around her gas station, complimented me on her way out. And I swear, Angel, the mine’s two-hundred-fifty-pound truck driver, he of the aura of constant menace, he of the incredibly inaccurate name—Angel actually smiled at me.

I think. It might have been indigestion.

But then he tipped me. Ten whole percent, which is a one hundred percent increase over his previous tips.

Ben hums as he dusts the cookies with powdered sugar. “I had to make them circles. What kind of Christmas-themed diner doesn’t have cookie cutters?”

“The kind that doesn’t offer gingerbread on the menu.”

“Right, which, again: how does that make any sense?”

“None of this makes any—oh, no, what time is it?” I dart to the bathroom and shake Candy awake. “Ten minutes until your shift is over.”

She sits with a start, the blood draining from her face.

“It’s okay. You have time. Get cleaned up.”

I clear the tables, and Candy emerges right as Jerry walks in. His eyes, gray and dull as sharkskin, take in the abnormally busy diner. I can see him calculating.

Candy lifts a trembling hand. “Hi, I—there’s a reason—”

“You dropped your pad.” I stand in front of her. “Here.” I dig out my tips from my jeans and shove them into her apron pocket. She can’t even look at me, but she squeezes my arm as she passes. And then I watch, Frank Sinatra crooning at me to have myself a merry little Christmas, as my tips go directly from her pocket into Jerry’s hand.

Merry effing Christmas yourself, Frank.

* * *

I make it through the next hour until closing time. Everyone wants to linger, huddling around the old television playing a repeating loop of a log-burning fireplace. They’re laughing, talking, acting like friends. Like people who are happy to be in Christmas.

“Feliz Navidad” stabs into my ears from the speakers, and I can’t handle it anymore. I took a shift that wasn’t mine, and I didn’t even get my stupid tips. Ben emerges just as I’m about to scream for everyone to leave.

He’s carrying a tray of gingerbread cookies. There’s a near-visible trail of scent, which reaches out and tugs the customers after him. He holds the door open and gives each person a soft, warm cookie, and an even softer, warmer smile as they leave. And then they’re gone. I flip the sign from “Merry and Bright” to “Closed for the Night” and deadbolt the door.

I turn, fists on hips, and direct my anger at the only person left.

“I’m not sharing my tips with you.”

Ben holds out a cookie. “Okay.”

“Usually we share tips with the cook. But I’m not sharing mine with you tonight.”

“That’s fine.” He pushes the cookie at me, but I swat it away.

“That’s all you’re gonna say? That’s fine?”

He looks down at the cookie like I’ve hurt its feelings. “Yeah, I mean, they’re your tips. You can decide what to do with them.”

“Of course I can. But we’re supposed to cut you in.”

“If you don’t think that’s fair, I understand.”

I throw my hands in the air. “You’re supposed to get mad at me. Then I can yell at you and feel better about everything.”

He laughs. “How would that make you feel better?”

“Because I want to yell at someone!” I slump into a booth and pick at a chipped spot in the Formica table. Ben slides in across from me, setting the cookies between us. Whether as an offering or a barrier, I can’t say.

“Who do you really want to yell at?”

“Ugh. I don’t know. Candy, maybe. Her dumb, creepy boyfriend, definitely. My mom and Rick, sometimes. And I’d share my tips with you, but I don’t have any, which means I worked all afternoon for nothing.” I rest my head on the tabletop.

“No one tipped you?” He finally sounds outraged.

“Everyone tipped me. But I gave it all to Candy.”

“Well, you earned a cookie.”

“I don’t like gingerbread.”

“That’s because you’ve never had my gingerbread.”

I narrow my eyes. “Is that some sort of chef pickup line?”

He blushes. The way the red blooms in his cheeks as he struggles for an answer is almost too sweet to handle, so I grab a cookie to let him off the hook.

“Díos mío. What did you put in these? Are they laced with crack? Gingerbread cookies are supposed to be hard and crunchy. Not good. These aren’t normal.” They’re soft, not quite cakelike, more like the consistency of a perfect sugar cookie. The spices zing my taste buds without overwhelming them—a dusting of powdered sugar counteracts the fresh ginger—and the whole thing is warm and wonderful and tastes like Christmas used to feel. How did he do that?

“See?” he says. “Not a pickup line.”

“Good, because that would’ve been super lame.” I take another cookie and lean back into the cushioned booth. Usually at the end of a shift I feel heavy, leaden, and ready for bed. But right now I feel light and soft. Like these cookies.

So I take a third. And, feeling generous, I decide to be nice to Ben. It’s not a hard decision. He’s kind, and even if he weren’t the only guy around my age in Christmas, he’d still probably be the prettiest one. “Everyone loved your food.”

His voice is shyly delighted. “I’m glad.”

I’m glad, too. He’ll make the time until I get out of here far more bearable. Maybe even exciting. “So, where’d you learn to cook?”

“Juvie.”

I sit up. “Juvie? As in juvenile detention?”

His face loses none of its pleasant openness as he nods.

“When were you in juvie? What for? Did my mom hire you straight out of their kitchen or something? I knew there was a reason why you were willing to work here.”

He laughs. “I’ve been out for six months. I applied for this job because I love Christmas, and it felt like … fate. Or serendipity. Or something. And I don’t like thinking about the person I used to be, so if it’s okay, I’d rather not talk about it except to say that I wasn’t violent.”

I wilt under the weight of my curiosity. “Fine. But it’s gonna kill me.”

“It’s not, and neither am I, because again, not violent.”

I flick some crumbs at him. “I gotta get cleaning.” I stand, stretching, and remove my apron. Ben is staring at me. I raise my eyebrows. He looks away quickly, embarrassed, but I’m more than a little glad I’m not wearing my uniform tonight.

I survey the damage. Not too bad. Mostly it’ll be dishes, but I’ll mop up and wipe down the tables first.

I switch off the sound system in the middle of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside.”

“Thank you!” Ben shouts from the kitchen. “That song is the worst.”

“I know, right?”

“Also terrible? ‘Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.’”

“Santa as Big Brother. Just imagine his posters, staring at you from every wall. SANTA IS WATCHING.”

“I love Christmas, but Santa is creepy.”

“Thank you, yes! No one understands. If someone is watching me sleep, it had better be a hot vampire, otherwise I’m calling the cops.”

Ben laughs and dishes start clanging. He must be prepping some food for tomorrow. I put in my earbuds and clean, dancing along to Daft Punk. Candy introduced me to them back when she still liked music. When I finally finish, I wheel the yellow mop cart to the kitchen, bone-tired and not looking forward to the dishes.