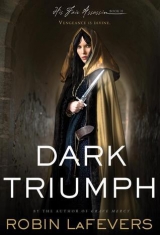

Текст книги "Dark Triumph"

Автор книги: Robin LaFevers

Соавторы: Robin LaFevers

Жанры:

Любовно-фантастические романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Duval leads us to a small chamber guarded by two sentries, who step forward to open the door to admit us. The duchess stands at a large table flanked by three men who stare at the map in front of her. One is dressed in travel-stained clothes and it is clear he has only just arrived. The second man is dressed in bishop’s robes and hovers near the duchess like a fat scarlet toad. The third is slender and serious, his brow wrinkled in thought. With relief, I realize I recognize none of her advisors, which means they will not recognize me.

It is the first time I have seen the duchess up close. She is young, and short, with fine skin and a high noble brow. Even though she is but thirteen years of age, there is something regal about her that commands respect. At the sound of our entry, they all look up, questions in their eyes.

Duval’s smile transforms his face. “Beast is here. In Rennes.”

The duchess clasps her hands together as if in prayer and closes her eyes, joy lighting her young face. “Praise God,” she says.

“I rather think we should be praising Mortain,” Duval says dryly, “as it is His hand that guided him here.” He motions in my direction, and all eyes turn to me.

“Then you and your saint have my most sincere thanks and profoundest gratitude,” she says.

I sink into a deep curtsy. “It was my pleasure, Your Grace. However, I bring you not just your noble knight but vital information concerning Count d’Albret and his plans.”

“You mean the man is not content to steal my city out from under me and sit on it like a brooding hen?”

“No, Your Grace. Even now he has put into motion a number of plans, any one of which could bear rich fruit.”

The thickset bear of a man on the duchess’s right gestures with his hand. “By all means, share with us these plans.”

“Count d’Albret, Marshal Rieux, and Madame Dinan hold the city against you, and while there are many who remain loyal to Your Grace, Count d’Albret does his best to make it . . . difficult for them to remain so.”

“Wait, wait. Start at the beginning. How were they able to take the city from the attendants and retainers who were still in residence there?”

Before I can answer, there is a rustling behind me, a sound that reminds me of a snake slithering in dry grass. In that moment, I recognize why I am uneasy: I sense eight pulses but see only seven bodies before me.

Slowly, as if I am in a dream, I turn around and see the abbess of Saint Mortain standing behind me. She skulks in the far corner, like a spider, which is why I did not see her when I first came in. Her blue eyes study me coldly, and my heart plummets like a stone.

I have not escaped my past; it has been waiting for me here all along.

Chapter Twenty-Four

“GREETINGS, DAUGHTER.” While her words are friendly enough, her voice is cool, and the kiss of welcome she gives me is as cold and impersonal as Death Himself. “Excellent work. We are pleased that you were able to perform your tasks so admirably.”

I curtsy deeply, my eyes watching her warily. Ismae and Annith always got along well with the abbess, and genuine fondness seemed to exist among them. Indeed, Annith was treated like a court favorite much of the time, and Ismae always saw the woman as her savior, as if it were the abbess’s own hand that had lifted her up from her drab life as a peasant.

The abbess and I had a different sort of relationship. One built on mutual dislike and distrust, brought together only by our shared needs: mine for a sanctuary, hers for a finely honed weapon she could let loose as Mortain willed. I trust her as much as I do a viper.

She motions for me to rise, then she turns to the others in the room. “I would remind you that Sybella has traveled far and at great discomfort and risk. No doubt she would like to make herself presentable before she tells the rest of her tale.”

At her words, I am suddenly aware of just how filthy and travel-stained I must appear, as if I am some grub that has scuttled out from under a rock.

The duchess is quick to apologize for her lack of hospitality and insists I take the time to refresh myself before reporting to the council. I had been so concerned with sharing my news that I had given no thought to my appearance until the abbess pointed it out. The evil cow. She likely did it on purpose, to throw me off balance.

My unease increases when the abbess insists on escorting me to my chamber herself. Ismae sends me a nervous glance as I curtsy to the duchess and then follow the reverend mother from the room.

As we walk, she says nothing except to order a servant to fetch things for a bath and make the room ready. She holds her head high, her posture rigidly straight as she glides down the hall. I do not know if her silence is because she fears being overheard or if it is yet another way to unnerve me.

We reach a chamber with a cheerful fire. A tub has been placed in front of it, and two maids are emptying kettles of hot water into the bath. The abbess quickly dismisses them. Once we are alone, she turns to face me, her beautiful face contorted with anger. “What are you doing here, Sybella?” she hisses. “You were only to free him, not personally escort him to Rennes.”

I toss my head in the face of her anger, both to give myself strength and to annoy her. “And how would he have gotten here, with me practically having to carry him from the dungeons? It was only after days of my tending his wounds that he was even able to stay on a horse—and then only when he was tied on.”

The abbess’s nostrils flare in irritation, for as much as she longs to, she cannot argue with my logic. She shoves her hands in her sleeves and begins pacing. “But now we have no one in Nantes.”

“It does not matter, Reverend Mother, for none of the traitors was marqued. Not Marshal Rieux, not Madame Dinan, and not d’Albret.” I watch her carefully to see if she recognizes that her promise to me—that I would be able to kill d’Albret—was broken.

She does not. “There is still great value in having you there. Someone will need to keep the duchess informed.”

And suddenly I am furious. Furious that she does not even care that she lured me back to hell on earth with a false promise and that for a span of time, death was more inviting to me than the life I was forced to live—the life she had forced me to live, using lies and a lure she knew I would find irresistible.

I take a step toward her, my hands clenched into fists so that I will not slap her. “Great value? Great value? For whom? And at what cost? You promised me I could kill him. Promised me Mortain had marqued him and was waiting for me—not any of His handmaidens, but me—to go back there and kill him. You lied to me.”

She tilts her wimpled head and studies me. “Something as paltry as a lack of Mortain’s permission would not stop the Sybella I know. Perhaps in the end, your ties to d’Albret are stronger than your ties to Mortain. You have, after all, known him and served him far longer.”

Her words strike all the air from my lungs and I am so shocked by a sense of violation that I cannot dredge up anything to say and am left gaping at her like a fish.

She gives me a scornful glance. “Make yourself presentable so you can report to the duchess,” she says, then lifts her skirts and sweeps out of the room.

As I stand in the empty room, the abbess’s words echo in my head and take up residence like a nest of maggots in a rotting corpse. I feel small and tainted, as if I should not be in this room, this palace, this city. I start to rub my arms, then stop, for my skin feels flayed raw by her accusation.

Then, praise God and all His saints, the anger comes, a sweet hot rush of fury that burns the pain I am feeling to ash. I have done what I was told to do, what I promised I would do. I have risked much and ventured back into my worst nightmares, all because I believed the abbess—believed that even though she did not like me, her service to Mortain would ensure that she would be truthful with me, see me as a useful tool, if nothing else. But clearly I have been duped and have allowed myself to be the worst kind of pawn.

Even worse, I wasn’t able to accomplish the one thing that would have made it all worthwhile—killing d’Albret.

Anger surges through my body, so powerful that I shake with it. I glance around the chamber, desperate for something to break, to throw, to destroy, just as the abbess has destroyed me. But there is nothing. No mirror nor crystal, only the candles, which would start a fire if I threw them, and while I am angry, I am not angry enough to bring down the very castle that holds us.

Which is something, I guess.

Instead, I cross to the bed, grab a handful of the thick, burgundy damask curtains, wad them up in my fist, then shove the wad into my mouth and scream. The relief of all the anger and fury leaving my body is so sweet that I do it again, and again. Only then do I let the crushed, wrinkled fabric fall from my hand, and I turn back to the room, somewhat calmer.

I will leave this place, leave Mortain’s service. I have warned the duchess of d’Albret’s plans. Once I have told them all that I know about his intent to infiltrate their defenses, my duty is done. And my duty to Mortain? I snort like one of Guion’s pigs. Look what my service to Him has gotten me so far.

Heartened by this decision, I reach behind and begin to unlace my gown, thrilled to be able to step out of its grubby drabness. I walk naked to the tub and am pleased to find the water scented with lavender and rosemary. The duchess, at least, is not stingy with her hospitality. Slowly, and with a great sigh of contentment, I lower myself into the water.

The heavy curtains are drawn against the cold winter winds, and the room is lit only by the fire burning in the hearth and a brace of beeswax candles. As I sit there, I imagine all of my anger being drawn from me and let it flow out of me into the warm scented water, for I will not be able to make effective plans if my vision is clouded by my own anger. I lean forward and dunk my entire head so that I may wash it, too. Who knows what vermin I have picked up over the last few days’ travels?

Just when I pull my head back up and am rubbing the drips out of my eyes, there is a soft knock at the door. “Sybella?”

At the sound of Ismae’s voice, I call, “Come in.”

The door opens, then closes as Ismae hurries into the room. “I’ve brought you some clean clothes,” she says, pointedly not looking at me naked in the bathtub.

Her familiar modesty cheers me, and I lean back and place my arms along the sides of the tub, fully exposing my breasts, just to fluster her. However, she knows me too well and simply rolls her eyes at me. “Would you like me to wash your hair for you?”

I find that I would, surprised at how much I missed the kind, gentle touch of friendship. Because I want it so much, I only shrug. “If you wish.” I do not think she is fooled, for she plucks an empty ewer from one of the tables and moves behind me.

We are both silent as the warm water sluices down my head and falls across my back. “I have been so very worried about you,” she whispers. “Annith checked the crows daily for word of your whereabouts and safety, but there was nothing. And no matter how many doors she listened at, she could not catch a whiff of where you’d been sent or what your assignment was. When you didn’t come back for months, we began to fear the worst.”

“And now you know. I was sent to d’Albret.”

Behind me, I feel a shudder run through Ismae’s body. “I do not understand how the abbess could ask that of anyone.”

For a moment, a brief, reckless moment, I consider telling Ismae the truth—that it was my own family I was sent back to—but I am not sure I am willing to risk it, not even with her.

“I must write to Annith. She will be so relieved to hear you are safe. She’s checked every message that’s come to the convent since you left, desperate for news of you. Better still, once you are rested enough, you should write her yourself.”

“I will,” I say, halfheartedly, for the plain truth is, I am jealous of Annith, safe and snug behind the convent’s walls. I have never envied her special place in the convent’s heart more than I do now. “Has she been sent out yet, or is she still waiting in vain for her first assignment?”

Ismae hands me a linen towel with which to dry myself. “How did you guess that all this time, they never intended to let her set foot out of the convent? I received a message from her just after you left for Nantes.” She takes a step closer to me. “Sybella, they mean to make her the convent’s new seeress. Sister Vereda is ill, and they want Annith to take her place.”

Is that why there was no order to kill d’Albret? Not only could I not see it, but neither could Sister Vereda? “At least she will be safe,” I say, thinking of how often I longed to be back behind those thick, cloistered walls.

“Safe?” Ismae asks sharply. “Or suffocated? If memory serves, you could hardly bear being held behind those walls for three years, let alone the rest of your life.”

I wince at the memory and cannot help but marvel at how hard I worked to escape the convent when I first arrived. I remember Nantes, d’Albret slaying those loyal servants, the look of terror in Tilde’s eyes, and the scratching at my own door. “More fool I,” I say quietly.

As she helps me into a clean gown, the look on Ismae’s face softens. “Assigned to d’Albret’s household, you have faced more horrors than any of us. But truly, Sybella, I do not think you understand how hard it is to be left behind, to feel as if you will never be given a chance to prove yourself or make a contribution. Especially for one such as Annith, who has trained for this her entire life.”

“She would not survive a fortnight outside those walls,” I say, my voice harsh.

Ismae sends me a disappointed look. “She will never know now, will she?”

Since I do not have the heart to argue with her, I change the subject. “What is between you and Duval?”

She makes herself very busy pouring us each a goblet of wine. “What makes you think there is something between us?”

“The way you look at each other. That and the fact that you listened to him when he told you you could not kill whomever you were talking about. So, do you love him?”

Ismae nearly drops the goblet she is handing me. “Sybella!”

“You are in love.” I take the goblet and sip the wine, trying to decide what I think about that.

“What makes you say such a thing?” she asks.

“You are blushing, for one.”

She fiddles with the stem of her goblet. “Mayhap I am embarrassed you would ask such forward questions.”

“Oh, do not be such a stick-in-the-mud. Besides, remember who taught you how to kiss. Duval has much to thank me for.”

Unable to restrain herself, Ismae picks up the wet towel and throws it at me. “It is complicated,” she says.

For some reason, I think of Beast. I swirl the wine in my goblet. “It always is,” I say, then drain the cup.

“He’s asked me to be his wife.”

This surprises me, but it also makes me like the man more. “Are you not still married to the pig farmer?”

“No. It was never consummated, and the reverend mother had it annulled the second year I was at the convent.”

“What did you tell him?”

“That I would think about it. For, while I love him, and will do so always, it is very hard to give anyone that kind of power over me again.”

“What did the reverend mother say?”

Ismae wrinkles her nose and refills her goblet. “It is just one of the reasons I have fallen so far out of her favor.”

“You? But next to Annith, you were her favorite.”

“No.” Ismae gives a firm shake of her head. “It was not I who was her favorite, but the blind, adoring acolyte that she loved.”

And that is when I know just how fully Ismae has changed.

Before we can talk further, there is a knock at the door. Ismae answers it, and a whispered, urgent conversation takes place before she closes the door and turns back to me. “The council meeting will not be resumed until tomorrow. The duchess’s sister has taken a turn for the worse, and the duchess wishes me to mix a sleeping draft for her.”

I arch an eyebrow. “You are a poisons mistress, not some healer for hire.”

Ismae gives me a sad smile. “It is a dance with Death, nevertheless.”

Chapter Twenty-Five

SINCE I AM DRESSED IN one of Ismae’s habits, the guard at the palace door salutes respectfully and makes no move to prevent my leaving. I step out into the cold night air and head toward a bridge that is lit by a sparse row of torches whose light is reflected in the dark water below.

It also leads to the convent where Beast is being held. I need to assure myself that I did not bring him all this way only to have him expire while in the sisters of Saint Brigantia’s care.

I reach the main gate at the convent and find it closed. Just to the right of the gate is a large bundle of what looks like rags. It takes me a moment to realize it is a sleeping Yannic, as loyal as the most faithful of hounds and no doubt banned from the convent for being a reasonably healthy man. Only ill or wounded men are allowed through those doors. I consider ringing the summons bell and announcing my presence to the entire convent, then reject the idea. What if they will not let me in? Or worse, what if they ask why I am here? For a moment, uncertainty grips me. Surely Beast has no need of me. Not now, when he is surrounded by the most skilled healers in our land.

I pause. Why am I here?

He is safe. And will soon be in a position to help the duchess. My role in his life is done. I saved him from d’Albret, the way I could not save Alyse. That should be enough.

So why do I feel this need to linger? Why this reluctance to part?

If I were anyone else feeling this, I would name it love, but I—I am far too smart to ever give away my heart again. Especially when to do so is as good as a death sentence for those I care about.

The old, familiar swirl of panic tries to surface. Instead of fighting it, I try to open myself to it, to let it come.

I remember the screaming. And the blood.

And that is as far as I get before the memory dissolves into pain.

Frustrated, I turn and follow the high walls surrounding the nunnery, looking for a low section or a back gate with a lock I can pick.

That is when I spy the lone branch. It is thin, too thin to bear a man’s weight, which is most likely why the nuns have not cut it down. But it is not too thin for me.

I toss my cloak over my shoulder, then look for a sturdy burl I can use as a foothold. It is a long stretch to the next branch, which hovers just out of my reach, so I must shimmy up the trunk, most likely ruining Ismae’s habit.

Since it belongs to the convent, I do not mind overmuch.

My hand closes around the branch, and victory surges through me as I pull myself up. The limb creaks and bows, but does not break. Lying flat to distribute my weight evenly, I begin inching across, hoping the limb will not snap and send me plummeting to the ground, breaking my neck. Mortain cannot have brought me this far for such an ignoble end.

At last the wall is below me. I swing my feet down onto it and let go of the branch, which springs back up. I stop to survey my surroundings. This convent is laid out much like the convent of Saint Mortain. I can make out the long low building that is the nuns’ dormitory, and the larger refectory. And, of course, the chapel itself. But where would they keep the sick and wounded?

A building set aside from the others has a faint light coming from one of the windows. That is as likely a place to begin my search as any. Perhaps a lone candle or oil lamp burns so the nuns can oversee their sleeping patients.

I lower myself from the wall into a garden filled with greenery. My boots crush the plants, releasing the pungent odor of herbs—the ones the sisters of Brigantia use for the famous healing potions and tinctures.

The very same ones we at the convent of Saint Mortain use to mix our equally infamous poisons.

I make my way to the path, trying to crush as few of the plants as possible, then follow the flat, round paving stones to what I hope is the infirmary. Near the door, I stop and press myself up against the building, using the shadows to conceal my presence. I close my eyes and try to feel how many are in the building.

I immediately sense a strong, booming pulse and nearly smile at how easily recognizable Beast is. There are other pulses that are thin and weak—patients’, perhaps. The second slow and steady pulse is most likely that of the sister who tends them.

It is my hope that I can slip in undetected, see how Beast fares, then simply slip out again. My plan is foiled, however, by the old nun who sits near the door quietly mixing something with her mortar and pestle. I am certain I make no noise and equally certain that the thick pool of shadows near the wall conceals my presence. But something alerts her, for she starts and looks up. Since there is no point in pretending, I step away from the wall, prepared to explain why I am here.

Her eyes widen as she takes in the habit I wear, and the hand gripping the pestle turns white. “Who?” she whispers. “Who have you come for?”

I cannot decide which annoys me most, her fear or her assumption that I have been sent to kill one of her patients. “No one, old woman. I merely come to see how the one called Beast fares. I escorted him here from Nantes and would like to see with my own eyes that I did not do so only for him to perish in your care.”

She bristles, her fear forgotten. “Of course he will not perish in our care.” Her face softens. “Are you the one named Alyse? For he calls that name in his sleep.”

“No, that is his beloved sister, dead these past three years.” The depth of my disappointment that it is not my name he calls takes me completely by surprise.

“Ah,” the old nun says sympathetically, as if she somehow knows what I am feeling. “Then perhaps you are Sybella. That is the name he asks for when he is awake.”

A flutter of joy quickens my pulse. I scowl so that she will not see it.

“However, he is asleep now,” she continues. “Indeed, we had to give him a tincture of opium and valerian in order to calm him. He was most insistent that he could walk out of here and be of use to the duchess, even though his body said otherwise and he could barely keep his eyes open, let alone sit up.”

“I will not wake him,” I promise. “I only wish to assure myself that he is well.”

The nun nods her permission, and I start to move away, but she stops me. “By the way, whoever tended his wounds on the road did an excellent job. The man owes that person not only his life, but also his leg.”

Her words please me far more than they should, this knowledge that my hands can heal as well as kill, and it takes every ounce of self-control I have to keep my pleasure hidden. I turn and begin making my way to where Beast lies.

One-third of the beds here in the infirmary are occupied, mostly with the elderly and frail. It is eerily still. No fretting or moaning or frail cries for help. Perhaps she has sedated them all.

It is easy enough to pick out Beast’s hulking form, even when it is draped in white linen bedsheets, for he is easily twice the size of any other patient here. I am pleased to see the beds on either side of him are empty. That should afford me some small measure of privacy.

He lies as still as if he had been carved from marble, the high color he normally boasts leached from his face by the dim light and fatigue. His face is made even uglier by the harsh planes and shadows revealed by the flickering light from the few oil lamps in the room. His eyelashes—thick and spiky as they rest against his cheeks—are possibly the only beautiful things about him.

I marvel at this man who carried me away from my waking nightmare, determined that I not fall victim to d’Albret’s terrible retribution. Even after I had done nothing but spew vile accusations at him to light his temper, he would not leave me behind. What does he see when he looks at me? A harridan? A shrew? Some spoiled noblewoman playing at helping her country?

I glance back toward the attending nun and see that she has dimmed the oil lamp and now lies on her cot, resting until one of her patients needs her. With no one to see, I plunk myself down on the floor and lean back against the bed frame. It is quiet. So quiet. I can hear the breath move in and out of Beast’s lungs, hear the blood move through his veins, hear his pulse, strong and steady and alive. Slowly, some of the terror of d’Albret’s pursuit begins to seep out of me. Beast stirs in his sleep just then, his good hand slipping out from under his covers to hang over the side of the bed.

I stare at his hand, its thick, blunt fingers and multitude of scars and nicks. Unable to resist, I slide toward it, wondering what that hand would feel like resting on my shoulder.

“I knew that you would miss me.”

It is only a lifetime of training that keeps me from leaping to my feet at the sound of Beast’s voice. I snort to mask the small noise of surprise that escapes my throat. “I did not miss you. Merely wanted to be sure my effort in getting you here wasn’t wasted.”

“They drugged me,” he says with mild outrage.

“Because you were too stupid to lie still and let your body heal.”

“You didn’t drug me,” he points out.

“Because I had to get your maggoty carcass from one end of the country to the other. Once we arrived, trust me, I would have drugged you too.”

“Humph.” We are both quiet a moment, and then he asks, “What of the duchess?”

“She will no doubt come visit you herself. As will Duval and the entire small council, most like.”

He shifts uneasily and plucks at the covers on his bed. “I do not wish to receive them like this. Trussed up like a babe in swaddling.”

“To them you are a hero, and they wish to thank you for your sacrifice.”

He makes another rude noise.

“Are you certain you are not an ox in disguise?” I ask.

In answer, he just grunts again. “I am surprised they have not sent you off to rescue some other fool knight while I slept.”

“Not yet.”

“If they are not careful, soon they will have men locking themselves in dungeons so that you can rescue them.”

“Then they shall undoubtedly perish, for I would not go through that again.”

“Where is Yannic?”

“Camped just outside the convent walls. Except for patients, no men are allowed inside.” I wait to see what his next question will be, then hear a faint rumble from his chest. He has fallen asleep. I allow myself a tiny smile, for if he is well enough to spar with me, then he is well enough to live. I settle myself more comfortably on the floor and promise I will stay only a few more moments.

I awake some time later from a dreamless sleep. As I blink, I see that the flames in the lamps are sputtering as the oil grows dangerously low. Not quite morning yet. I feel the heavy weight of Beast’s hand still on my shoulder, then slowly inch myself out from under it, not wanting to wake him.

Not wanting him to know precisely where and how I spent the night.

I pause outside the convent and turn toward the city gate. I could leave now. I could simply walk down this street to the city gate, go across the bridge, and be gone from this place forever. No more abbess. No more threats of d’Albret.

But the stark truth is, I have nowhere to go. No home to return to, no kin to offer me shelter, and the convent will no doubt be closed to me now.

I could work as a tavern maid—if they would hire me. In troubled times such as these, people are reluctant to trust strangers.

I could even seek out Erwan and throw my lot in with the charcoal-burners. Or return to Bette and marry one of her sweet, eager sons. I could control either of them well enough.

Except they have sworn to fight at Beast’s side in the coming war.

The grim reality of my situation nearly makes me laugh. I am beautiful and educated and have all manner of useful—and deadly—skills, but all of that together is worth less than a bucket of slops.

I pull my cloak close around me against the chill breeze and continue across the bridge. As I draw near the gatehouse, I quickly rearrange my weapons, making sure that the dagger at my waist is clear and visible and that my wrist sheaths peek out from under my sleeves. Better that they think I was out on an assignment for Mortain than suspect I spent the night curled at the feet of the Beast like a mournful dog.

The guard on duty nods, his eyes taking in my habit and my weapons, and waves me through. The convents of the old saints seem to receive proper respect here in Rennes.

I reach my chambers and am relieved to find them empty. Too tired to remove my gown, I simply loosen the laces, climb into bed, and draw the bed curtains closed to block out the morning light. I pray that no one will have need of me for the next few hours, for I will be useless until I can get some sleep.