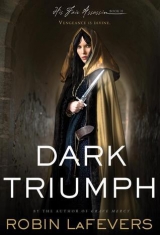

Текст книги "Dark Triumph"

Автор книги: Robin LaFevers

Соавторы: Robin LaFevers

Жанры:

Любовно-фантастические романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Chapter Thirty-Six

THE RISING SUN HAS NOT yet shown its face when we get on the road, but at least it is no longer full dark. Even so, we walk the horses until the sun breaks over the horizon, then Beast gives the command to gallop, the urgency of our mission pressing at our backs.

Beast himself rides up and down the line, being sure to greet each man warmly or share some private joke with him. As he does, the men sit up straighter or square their shoulders, their hearts feeding on that encouragement as much as their bodies feed upon bread.

I think of my father, my brothers, and how they command men. They use fear and cruelty to whip them forward and bend them to their will. But Beast leads not only by example but by making the men hungry to see themselves as Beast sees them.

Just as I am hungry to believe I am the person he sees when he looks at me.

I am terrified of whatever is springing up between us.

Of just how badly I want it.

My own feelings for him began well before we reached Rennes, when he first told me he went back for his sister. But my belief that he wouldn’t—couldn’t—care for me in return created a moat of safety around my heart, and I had nothing to fear because the entire situation was impossible.

But now—now I look in his eyes and I see that he believes it is possible. Surely that is only because he does not truly know me. There are still things—momentous things—that I have kept from him. And while Beast is strong and his heart generous, I am not certain he is strong enough to love me and all my secrets.

I cannot decide if I should bury the rest of those secrets so deeply that they will never resurface or throw them in his face like a gauntlet. Better he hate me now rather than later when I have grown used to his love.

But haven’t the gods already proved how futile it is for me to try to keep my past hidden? Which leaves me with one clear choice—one that has me wishing I had decided to obey the abbess and make for d’Albret’s camp.

“Why so grim, my lady?”

I glance up, surprised to see Beast riding next to me. How can someone so large move so quietly? I open my mouth to ask him that very question but surprise myself by asking a different one. “Do you know that I have killed more than thirty men?”

His eyebrows shoot up, whether at my confession or the number of kills, I cannot say. “And of those, only sixteen were sanctioned by Mortain.”

When he says nothing, I add somewhat impatiently, “I do not kill simply because Mortain ordains it, but because I enjoy it.”

“So I have seen,” he says. “I, too, take great pleasure in my work.” He looks around us. “Is there someone here you wish to kill?”

Uncertain if he is teasing or serious, I resist the urge to reach across the space between us and punch him. Clearly, to a man who is rumored to have killed hundreds upon hundreds in battle, my puny body count does not hold much sway. Perhaps something that he has had less personal experience with. “I am wicked and carnal and have slept with lots of men. Possibly even dozens.” Although in truth, it is only five.

Beast does not look at me but instead surveys the line of horses and carts stretched out behind us. “You hold yourself too lightly, my lady, for I cannot think of even a single man who deserves such a gift as you claim you have given.”

His words prick at something achingly tender, something I don’t wish to acknowledge, so I snort in derision. “What do you know of such things? I am likely one of the few maids who have not run from your ugly face.”

He turns back to look at me, amusement sparkling in his eyes like sunlight on water. “True enough, my lady.” Then he is gone, riding down the length of our party to make sure there are no stragglers, and I am left with the conviction that an avalanche would be easier to dissuade than that man.

Toward late afternoon, we reach a small forested area—a secluded place the charbonnerie scouts have picked out for us. The soldiers do not like it and grumble, for it is a dark, primordial tangle of trees and underbrush. Indeed, the trees here are so very large, their roots have burst from the ground and run along the surface, like the ancient bones of the earth itself. Although I cannot say why, I feel at ease in this place, as if the presence of Dea Matrona is strong. No. Not Dea Matrona, but the Dark Mother. For even though I do not worship Her, I can feel Her presence in the rich loam and leaf mold beneath our feet, and in the quiet rotting of the fallen logs. Perhaps that is what makes the soldiers uneasy.

Our party has grown throughout our journey, as if Beast is some mad piper whose tune calls eager young men who wish to fight at his side. In addition to the men-at-arms and original charbonnerie, we have been joined by a dozen more of the charcoal-burners, two blacksmiths, a handful of woodcutters and crofters, and three burly farmers’ sons. One of whom is Jacques, Guion and Bette’s elder son.

Soon, the clearing is full of the bustle and industry of nearly fifty people making camp ready for the coming night. I feel twitchy in my own skin, as if the very sap that runs through the trees is now running through my veins, bringing me alive after a cold, hard winter.

Wishing for something to do, I offer to help Malina prepare dinner, but she shoos me away. “You are a lady, and an assassin besides. You do not belong with the soup pot.”

I turn and survey the camp. Some of the charbonnerie are busily erecting rough tents in the clearing; others are collecting water from a nearby stream so that the tired horses may drink. The soldiers have gone off hunting for our dinner, and even the greenlings have been sent to gather firewood. Since I refuse to sit idly by while others do the work, I snag one of the slings for gathering wood and head into the trees.

Moving among the trees calms me. In that quiet and stillness, I find myself content, a feeling I barely recognize. I like this life—the days full of hard riding and the evenings filled with chores and necessities, with little time left for idle pleasures or twisted games.

Mayhap I can simply ride at Beast’s side as he travels throughout the kingdom raising an army to the duchess’s cause. That thought has me smiling, for it is a fanciful notion that I would not dare indulge in were I not out here alone with no one to see it.

But am I alone? Voices and some strange cracking noises reach my ears. I move forward cautiously, careful not to step on any dried leaves or twigs that might give me away.

I come upon a clearing and find it is only the boys from the camp who have paused in their wood collecting. They have taken two branches and are playing at sword fighting. They are strong boys, but their movements are clumsy and unskilled. The charbonnerie are right to call them greenlings. I start to smile at their antics, but instead a cold chill slithers down my spine. This is no game we play, and I suddenly despair of our chances—not only of success, but of survival.

I step from between the trees. “Fools!” I scold. “You are not beating the straw from mattresses!”

The boys freeze, their faces filled with both embarrassment and defiance. “What do you know of such things?” the woodcutter’s boy asks sullenly. “My lady,” he adds as an afterthought.

“More than you, it would seem. You do not whack each other as if chaffing wheat. There is a rhythm of thrust and parry, attack and counterattack that you must know else you’ll be gutted like pigs.”

Resentment flares in the young woodcutter’s eyes. I have pricked their male pride, and rubbed their noses in their lack of privilege, for of course they have had no opportunity to even witness sword fights, let alone practice at them. “There is not time in the three days before we reach Morlaix to teach you the art of sword fighting. That takes years. Add to that that there are no extra swords to be had, and you are wasting your time.”

“What would you have us do? Collect wood?” One of the blacksmith’s boys kicks at a branch at his feet in disgust.

“No,” I say, stepping closer. “I would have you learn a few quick, deadly ways to kill a man so that you can be of service to the duchess in this mission.”

The greenlings’ faces are mixtures of suspicion and hope. “And who will take the time to teach us these skills? My lady.”

I smile. “I will.” I reach for my wrists and pull my knives from their sheaths. The boys’ interest quickens, except for the blacksmith’s son, who is still skeptical.

“What can we learn of fighting from a maid?” he asks the others, and looks of doubt appear on their faces. Two of them actually snicker. I want to take their fat heads in my hands and knock them together like empty jugs.

Jacques speaks up. “That is no mere maid, you fool. Did you not hear the commander yesterday? She serves Mortain.” He lowers his voice. “She is an assassin.”

The blacksmith boy blinks. “Is this true?”

In answer, I take one of the knives and throw it. He has time only to gape in surprise before his cloak is firmly pinned to the tree behind him, right above his shoulder. “It is true,” I tell him.

Without further discussion, I turn to Jacques. “You will partner with me. The rest of you, pair up according to your size.” With a sheepish glance at the others, Jacques shuffles across the forest floor to stand in front of me, hands hanging limply at his sides.

I remove the two knives I carry in my boots and hand them to two other boys. “Just like an assassin, your greatest strength will be your stealth and cunning. And speed. You will need to get in quickly, strike, then move away before anyone has even realized you are there. That means in addition to what I teach you here tonight, you must begin to learn to move quietly. Right now, you sound like a herd of oxen galumphing through the forest. Pretend you are sneaking up on somebody if you must, but learn to move without making noise.”

“There is no honor in that,” one of the woodcutters snorts.

Quicker than he can blink, I step inside his guard, whip his belt from his waist, and twist it around his throat, just tight enough to get his attention. “There is no honor in throwing your life away either. Not when the duchess needs every man in her kingdom if we are to win the coming war.”

The boy swallows audibly, then nods in understanding. I step away and hand him back his belt. “Besides, if what you say is true, then those who serve Mortain have no honor, and I am certain that is not an accusation you care to make.”

They quickly shake their heads. “Now, the quickest and quietest way to kill a man is by slitting his throat, just here.” I run my finger across my own. “This is not only an excellent killing blow but also a way to silence him so he cannot call out and alert others.” I step into the lessons I was taught at the convent as easily as I step into a new gown. “Here. Put your fingers at your own throat. Feel the hollow at the base of it. The spot you want to strike is three fingers up from that.” I watch as they all grope at their own throats. “Good. Now I will show you the striking motion from behind.”

“On me?” Jacques asks, his voice cracking.

“Yes,” I say, hiding a smile. “But I will use the knife handle, not the blade.”

I spend the next hour teaching the greenlings some of my most basic and crudest skills. How to slit a throat; where to strike from behind so that a single blow will kill a man; where best to place your body when garroting someone so his thrashing will not dislodge your hold. We do not spend nearly as long as I’d like, but our wood is needed to feed the fires if we are to eat. They are all still awkward and clumsy with the movements, but now they have some small skills they can use.

That night, when we finally sit down to eat, I feel as if I have earned my supper.

When the meal is done and the fire burning low, I go in search of my bedroll. Someone—Yannic, I presume—has laid it out carefully between two of the great tree roots so that I am cradled between them. Near stumbling with exhaustion, I reach down to lift the blanket, then blink in surprise at the small clutch of pink flowers that have been laid on my pillow.

It appears that my sins are forgiven. At least, the ones Beast knows about.

Chapter Thirty-Seven

LATER, WHEN EVERYONE HAS RETIRED for the night, a large, hulking shape steps away from the dying fire and moves in my direction. “You look like a babe in a cradle,” Beast says.

I glance to the root on either side of me and decide I like his comparison. “Dea Matrona is holding me close.” I am certain I can feel the roots pulsing as they draw nourishment from the earth.

Being careful of his injured leg, he uses the tree to ease his way down to the ground beside me. “Have you finished confessing all your darkest sins to me?”

I am glad he can accept my earlier confessions with such a light heart, and clearly the gods are handing me this perfect moment for sharing the rest. I am grateful for the darkness that cloaks us, casting everything in shadow, muting life itself somehow. “Sadly, no.” I take a deep breath. “I would warn you that you are courting the very woman responsible for your sister’s death.”

A moment passes, then another, and still he says nothing. I peer through the darkness, trying to see his face, looking for some sign that my confession has addled his wits or left him speechless with revulsion. “Did you not hear me?”

“Yes.” The word comes slowly, as if he must haul it up from some deep well. “But I also know you are quick to paint yourself in the darkest light possible. How old were you?”

“Fourteen,” I whisper.

“Was it your own hand that dealt the killing blow?”

“No.”

Beast nods thoughtfully. “Can you tell me how a lone fourteen-year-old maid could stop one such as d’Albret?”

“I could have told someone,” I say in anguish.

“Who?” Beast says fiercely. “Who could you have told who would have had the means and the power to stay his hand? His soldiers, who were sworn to serve him? His vassals or his retainers, who had sworn similar oaths? No one could cross a dangerous, powerful lord such as d’Albret at the say-so of a mere child.”

“But—”

“All those things you did—or didn’t do—were a matter of survival. Telling anyone would only have exposed you as knowing the full scope of what went on in d’Albret’s household and endangered you even further.”

“It is not just that,” I say. “I was unkind and laughed when my brothers teased Alyse or played cruel jokes on her. I would laugh as loudly as they did.”

Beast’s jaw clenches, and it is clear that I have finally managed to make him see the extent of my cruelty.

“And what would have happened if you hadn’t?”

“Alyse would have had a true friend, someone to stand by her instead of someone who ran at the slightest threat.”

He leans across the distance between us, getting as close to my face as he can. “If you had not laughed at the cruelty, you would have become the next target.” He holds up a hand, stopping my flow of words. “Do not forget, I have seen you dreaming and know how much darkness haunts you. I am also fair certain that very little of it is yours. I say again, all those things you did—or didn’t do—were a matter of survival.”

We stare at each other for a long, hot moment, then my temper flares. “Why do you not have the good sense to see that I am not deserving of such forgiveness?”

He laughs—a harsh, humorless sound. “The god I serve is near as dark as yours, my lady. I am not one to pass judgment on anyone.”

As I stare into his eyes, I see the faint echo of the horrors of the battle lust he has endured, and understanding dawns. He truly knows some of the darkness I struggle with.

We sit in the deepening night for some time. His face is mostly dark angles and planes, with only the faintest glow of the fire reaching this far away. “I would like you to tell me how my sister died,” he says at last.

Even though he has every right to know this, my heart starts to race and it feels as if a great hand has wrapped itself around my chest. But Sweet Mortain, it is the very least of what I owe him. I close my eyes and try to grasp the memory, but it is as if a thick door bars my entrance, and when I struggle to open it, pain shoots through my brow and my heart beats so frantically I fear it will shred itself against my rib cage.

I remember the screaming. And the blood.

And then there is nothing but a black mawing pit that threatens to swallow me whole.

“I cannot,” I whisper.

Something in his face shifts, and his disappointment in me is palpable. “No, no,” I rush to explain. “I am not refusing or playing coy. I truly cannot remember. Not fully. There are just bits and pieces, and when I try too hard to force the memory, only blackness comes.”

“Is there anything you do remember?”

“I remember screaming. And blood. And someone slapping me. That is when I realized the screaming was mine.” The giant hand around my chest squeezes all the air from my lungs. Black spots begin to dance before my eyes. “And that is all.”

He stares at me a long moment and I would give years of my life to be able to see his face clearly, to know what he is thinking. Through the darkness, his big warm hand tenderly takes hold of mine, and I want to weep at the understanding in his touch.

The road to Morlaix takes us uncomfortably close to my family’s home. It sits but a few leagues to the north, and simply knowing how close it is makes my whole body twitch with unease. Beast says nothing, but I see his gaze drift in that direction a time or two and cannot help but wonder what he is feeling. Luckily, it begins to rain, soft fat drops that quickly turn into a torrential downpour, forcing our minds to other things. We cannot afford to stop, however, so we continue on. While no one complains, it is only the charbonnerie who do not seem to mind. By midmorning, the forest floor is muddy, and our progress is reduced to a slow slog. But as long as we can keep moving forward, we do. We must. Even now, d’Albret is likely camped in front of Rennes and giving the signal to his saboteurs. Please Mortain, let us have gotten all of them. And if not, let us hope Duval and Dunois are on their guard.

When the second horse flounders in the mud and it takes us an hour to dig out one cart’s wheels, Beast decides we must wait out the storm and sends scouts ahead to find us shelter.

A short while later, they return. “There is a cave a mile or so north of here,” Lazare tells him. “It is large and can hold all of us and the horses as well.”

De Brosse’s horse shifts uneasily on its feet. “It is an old cave, my lord. With strange markings and old altars. I am not sure the Nine would appreciate us trespassing.”

I laugh—mostly so they will not hear my teeth chattering with the cold. “Between us we serve Death, War, and the Dark Mother. Whom do you think we must fear?”

De Brosse ducks his head sheepishly, and Beast gives the command to head for the cave. I almost hope it is a mouth that opens directly to hell, for of a certainty, we could use the heat.

Chapter Thirty-Eight

EVEN AS HALF THE PARTY is still filing into the cave, the charbonnerie have torches lit and get to work building fires. The cave is indeed enormous. We could easily fit twice our company inside.

There is much stomping of feet, groans of relief, and creaking of leather and harness as fifty mounted men dismount and jostle to create room for themselves and their horses.

Once I have dismounted and handed my horse to Yannic, I pace the perimeter of the cave, trying to get blood flowing in my limbs. I would also like to know in whose abode we will pass the night. The charbonnerie call this place the Dark Mother’s womb, and it may well be, but other gods have been worshiped here, and more recently.

There is an old altar at the very back. The torches hardly cast any light that far, but I can see the faint outline of small bones, some offering made long ago. Old drawings flicker on the cave walls: a spear, a hunting horn, and an arrow. It is not until I see the woman riding the giant boar that I am certain we have stumbled into one of Arduinna’s lairs, where she and her hunting party would rest from their hunts.

Thus reassured, I return to the front of the cave, where the rest of the party stands, torn between getting comfortable and bolting.

It is the youngest of the men, the sons of farmers and woodcutters and blacksmiths, who are the most unsettled. The charbonnerie have no fear of this place, and the men-at-arms are too disciplined to show such fear, even though I can smell it on them as surely as I can smell their sweat. But the green boys stand huddled together, looking about with wide eyes, their shivers equal parts cold and fear.

“Arduinna,” I announce. “The cave belongs to Saint Arduinna. Not Mortain, nor Camulos, nor even the Dark Mother”—I send a quelling glance at Graelon, who looks to correct me—“but the goddess of love. There is nothing to fear.” Although that is assuredly a lie, for love terrifies me more than death or battle, but these youths do not need to know that. Indeed, Samson snickers then, and his gaze goes to Gisla, who is helping Malina set up pots for boiling. Now, that is what we need. The goddess of lust moving in all these men with but half a dozen women among them.

“Come,” I say sharply. “Grab your weapons and move to the back where there is room to spread out.”

Samson, Jacques, and the others gape at me. “Here?”

“Do you think your skills are so great that you may set aside your practice?”

“But there’s no room.”

“Oh, but there is. Now, follow me, unless you are afraid. Samson, Bruno, bring the torches.”

Of course, none will admit to such fear, and certainly not in front of me, so I lead the group deeper into the cave and have the boys secure the torches.

I place myself at the very back of the cave, for even though it is clearly one of Arduinna’s, I can feel Mortain’s cold breath upon my neck. I do not know why His presence should be so strong here, and I would not have the boys turn their backs to Him.

After much grumbling and complaining, the boys finally take their positions. “Begin,” I order, and their arms, clumsy with cold, start moving through the exercises we have been practicing. Within half an hour, the cold is forgotten, along with their fear, and they are concentrated on besting their opponents.

My focus on the greenlings is so great as I try to keep them from accidentally killing one another that it takes me a while to realize we have drawn a crowd. Easily a dozen of Beast’s soldiers have gathered round and are watching the boys with narrowed eyes and folded arms.

“My money’s on the smith’s boy,” de Brosse says. “The one with the long hair.”

“I’ll take that wager. I think the boy with the ax will win the bout.”

There is a rustle of purses and jingle of coin as bets are made. Their casual betting raises my hackles; this is no game. The boys’ lives likely depend on what they learn here. Besides, the greenlings do not need the distraction of being surrounded by true soldiers.

Or so I think until I see how the greenlings take the soldiers’ attention to heart. There—Samson has finally started taking the practice seriously, his face creased in concentration. Jacques, too, is no longer so worried about hurting his opponent and finally manages to wrestle him into position so that he can get the leather cord around his neck.

Cheers go up, and Jacques smiles shyly. Then Claude sneaks up from behind him and gets his knife handle around his neck. Another jingle of coin changes hands. I cannot decide if I am amused or annoyed that the soldiers’ opinions seems to carry more weight than mine. “Again,” I say. “And this time, Claude, try not to laugh as you slit your opponent’s throat.”

Dinner that night is a cheerful affair. Half of the soldiers’ purses are heavier from their wagers, and the greenlings’ sense of pride has grown in equal amounts. Even the charbonnerie seem to have relaxed some.

As men leave the fires to lie down on the cave floor, Beast comes to find me. I have selected a spot for my bedroll toward the back, still wishing to place myself between that faint chill of death that is haunting me and the others.

“We reach Morlaix tomorrow,” he says, easing down onto the ground.

I try to ignore the heat coming off his body, try to pretend he is not close enough for me to touch and that my fingers do not yearn to do just that. “I know.”

Beast reaches across the small space and takes my hand in his. It is a big hand, and hard, the entire palm filled with calluses and scars. “It was well done, you training the greenlings.”

“I know.” My answer startles a laugh out of him, but it is true—I do know that it was a good thing.

He shakes his head. “I fear I have lost my touch for commanding men. It is an assassin who has finally managed to bring them all together, not me.”

“Now you go too far and mock me. I do not have any knack for bringing men together.”

He threads his fingers through mine, then slowly brings my hand up to his lips and kisses it. “I would never mock you. I speak only the truth.”

It is the most comforting thing I have ever felt, that hand on mine, the quiet steadfastness it promises. That he offers me this after all the secrets I have told him humbles me. I want, more than anything, to keep that hand in mine and never let it go.