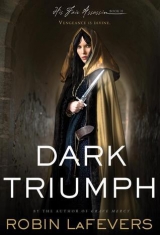

Текст книги "Dark Triumph"

Автор книги: Robin LaFevers

Соавторы: Robin LaFevers

Жанры:

Любовно-фантастические романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Chapter Eighteen

WE TRY TO GET AN early start the next day, but between the little gnome of a jailor, the wounded giant, and—what role do I assign myself? The charioteer?—we are like a mummers’ farce. At last we get the horses ready and the gear packed and—most difficult of all—the lumbering, crippled Beast onto his saddle. I am exhausted before we even leave the yard, but when we finally do, I breathe a sigh of relief.

In spite of what Beast claims, he is far from well enough to travel. We should stay at the hunting lodge another day or two to allow him more time to recover, but we dare not. While the lodge is well off the main road and not widely known, I have no doubt more of d’Albret’s men will find it soon enough. Luckily, I do not think it will be the first place they look, for they will assume we want to put more distance between ourselves and our pursuers. And they are right. The back of my neck tingles with foreboding.

Brisk winds have blown the rain clouds away, and the sky above is clear and blue. All that clear sky makes a perfect backdrop for the thin trickle of smoke that rises from the smoldering remains of the night-soil cart and its inhabitants nearly a mile away.

Please Mortain, let it buy us some time.

But in case it does not, we are each armed with weapons scavenged from d’Albret’s men. With Yannic’s help, Beast has altered a scabbard so he may wear the sword on his back within easy reach. I, too, have a sword, but it is strapped to my saddle next to the crossbow that hangs there. Beast has also purloined the woodcutter’s ax from its place near the lodge’s woodpile. It hangs from the left side of his saddle near his injured arm. Although how he expects to wield it, I do not know.

We ride out in silence. Beast is wisely conserving his energy, and I have far too much to think about to waste time in idle conversation. If all goes well, we should be there in four days. If the fever does not consume Beast’s weakened body, and if he can stay in the saddle, and if d’Albret’s riders do not find us.

My mind keeps running over what I know of the countryside, trying to think of the best route for us to take. The area around the hunting lodge is sparse woodland, which serves us well enough, but eventually we will come to fields or a road or, worst of all, a town. How many men will d’Albret have sent out, and where will they focus their search?

And how long can Beast stay in the saddle? Already his head nods and he looks to be dozing. Or perhaps he has fainted again. I nudge my horse over to him to check, surprised when his head snaps up, his eyes focused on the trees in front of us. “Do you hear that?”

I tilt my head. “What?”

We continue forward, but more slowly. “That,” he says, his head cocked to the side. “Raised voices.”

I stare at him in disbelief, for my own hearing is as sharp as anyone’s and I have not heard a peep. “Mayhap it is simply ringing in your ears from your injuries.”

He gives a sharp shake of his head and urges his horse forward.

“Wait!” I make a grab for his reins but miss. “In order to avoid trouble,” I remind him, “we move away from the noise, not toward it.”

His head swings around and he pins me with the full force of his intense gaze. “What if those are more of d’Albret’s men? Will we have some innocent pay for our freedom?”

“Of course not,” I snap. “But I am not used to this idea that your god allows you to kill at your own whim.”

Beast’s eyes narrow in that way he has that sees past my skin into my very bones. “My god allows me to save the innocent,” he says. “Does yours not?”

I am ashamed to admit that my god does not allow any such thing. “There are no innocents where Death is concerned,” I tell him, then move into the lead. We continue our approach, easing our horses forward until we have a clear view of where the noise came from. It is a mill house, its wheel turning briskly in a stream made fat by the recent rains. It is as peaceful-looking as a painting. “See? It was nothing. We can continue on our way with no one the wiser.”

Just as Beast nods in agreement, a man steps out of the mill and hurries toward us. When he is half a bowshot away, he stops. “The mill is closed today,” he calls out. “Broken, and needing repair.”

“Something is not right,” Beast says quietly. “The man is whey-faced, and sweat beads his brow.”

“My job is to get you to Rennes in one piece, not to stop and offer assistance to every peasant in need we come across. Perhaps he has simply been working hard this morning? Besides, once you dismount, I am not sure we can get you back on that horse.” But something isn’t right. The man’s heart is beating at a frantic pace.

“For one, he is a miller, not a peasant. And two”—Beast gives me a grin as infectious as the plague—“I can kill without getting off my horse.”

Easing my own horse forward with small, unthreatening steps, I allow myself to draw closer. “We have no need of the mill,” I call out to him. “We are just passing through and thought to refill our water skins.”

The miller wrings his hands. “This is not a good place for that. The bank is too steep. There is a much shallower access just a short way up the road.”

I nudge my horse to take another step, then another, and that is when I feel four more heartbeats nearby. One of those is lighter than the others but racing as wildly as the miller’s.

“Ah, but we are thirsty now.” I swing out of my saddle and onto the ground. “And the sound of all that sweet water so close by is like torture to our dry throats.” I keep my voice and movements light as I turn and remove one of the water skins from my saddle. While my body is blocking my movements, I also load and cock the crossbow, poke an extra bolt through the fabric of my gown, then unhitch the bow. I give Beast a pointed look, and he nods. Hiding the crossbow in my skirts, I turn around and head toward the miller.

He hurries forward, nearly dancing in distress. “No, no. You must not—”

I put one hand to my stomach as if I am ill and stumble into him. “Who is it they have?” I whisper. “Your wife? Your daughter?”

His eyes widen in fright, and he crosses himself, then nods.

“All will be well,” I tell him, and hope that it is not a lie. There! A glint of steel from the barn door. Another from the branches of the tree in the yard. “The barn!” I shout to Beast as I pull my crossbow out and aim for the man in the tree. I hear his grunt as the bolt finds him. Before his body hits the ground, I slap the second bolt in place. A girl screams and darts from the mill into the yard, followed by a soldier. He raises his crossbow in my direction, but mine is already trained on him, and my bolt catches him in the chest before he can release his own. The girl screams again as he tumbles to the ground, nearly taking her down with him. The man from the tree is not moving, and there is no heartbeat coming from the barn, so Beast’s aim must have been as good as mine. Just to be certain, I draw a knife before hurrying to the girl and the fallen soldier.

Beast steers his horse to the miller. “Peace,” he says. “We will not harm you. We merely wanted to stop trouble in its tracks.”

The miller’s relief is tempered with wariness and he begins talking fast, proclaiming his own innocence, telling how these soldiers, these thugs, showed up at their door and began beating and questioning them. “They had just gone into the mill to cut open all the sacks of grain when they heard you coming.”

It would, I admit, be a good place to hide. I let Beast deal with the outraged man and turn to the daughter. Her blouse is torn and she is breathing fast, too fast, as if she has run some great distance, and I can still feel her heart beating frantically in her breast, like a small, frightened bird. “Did they harm you?” I ask quietly.

She looks at me, her eyes wild with barely checked terror, then shakes her head no.

But I know it for a lie, even if she does not. Those men have destroyed her sense of safety for months—possibly years—to come. Unable to stop myself, I reach out and grip her shoulder. “It was not your fault,” I whisper fiercely. “You and your father did nothing to deserve this except be in the wrong place at the wrong time. It was not a punishment from God nor any of His saints—it was simply brutish thugs who happened upon you.”

Something in her frightened eyes shifts slightly, and I can see her grasp my words like a drowning man grabs a rope. I nod, then turn to retrieve my crossbow bolts.

We do not tarry long. Between Yannic and the miller and myself, we hoist the three dead bodies back onto their horses, and take the horses with us when we go.

“We will have to veer farther west if we wish to avoid d’Albret’s men,” I tell Beast as we ride away.

Beast nods in agreement, then grins. “I’ve never met a lady who enjoys her work as much as I enjoy mine.”

“My work?”

“Killing. Assassin-ing.”

“What are you implying?”

He looks puzzled at the anger in my voice. “That you are very good at what you do. It was a compliment, nothing more.”

Of course, he would mean it as a compliment. “Just how many other lady assassins have you met?”

“Other than you? Only Ismae. And she seemed to approach her duty with more earnestness than true joy, whereas you come alive with a knife in your hand.”

Hotly uncomfortable with his assessment, I fall silent.

Do I enjoy killing? Is it the act itself that brings me joy? Or do I embrace the sense of higher purpose it gives me?

Or do I simply enjoy having something at which I excel, as there are few enough skills that I possess?

However, if I do enjoy killing, how does that make me any different from d’Albret?

It is only Mortain—His guidance and blessing that separates us. And I have rejected that.

But Beast kills as well, efficiently and expertly, and does not seem tainted by the same darkness that colors d’Albret and myself. I have never seen anyone kill so cheerfully or eagerly, and yet he is light of heart. “How did you come to serve your god?” I ask, breaking a long silence.

Beast grows quiet, grim even. Just when I have decided that he is not going to answer, he speaks. “It is said that when a man rapes a woman while the battle lust is still upon him, any child that results belongs to Saint Camulos. I was such a babe. My lady mother was assaulted by a soldier while her own husband was off fighting against King Charles.”

“And yet she loved you and raised you as any of her other children?” I ask, somewhat in awe of her charitable nature.

Beast snorts out a laugh. “Saints, no! She tried to drown me twice and smother me once before I was one year old.” He falls silent. “It was Alyse who saved me, usually toddling in at just the right moment.”

“You remember that far back?”

“No, my lady mother was wont to throw it in my face at every opportunity. She was afraid of explaining my presence to her lord husband, but in the end, he never returned—he was killed on the fields of Gascony, pierced through with a lance.

“By then, I was nearly two years old, and little Alyse had grown fond of me. She rarely left my side in those years. I think she was afraid of what would happen to me if she did.” He grows quiet for a long moment before speaking again. “I owe Alyse my very life, and I failed her.”

I dare to ask the question that has been haunting me since I learned that Alyse was his sister. “Why did your mother wish for the marriage? Why did d’Albret, for that matter?”

“D’Albret pressed for the marriage because part of Alyse’s dower lands abutted one of his lesser holdings that he wished to expand. And she was young and healthy and able to bear him many sons. Or so our lady mother promised him.”

And thus sealed her daughter’s death warrant when Alyse could not. What sort of woman promises such things?

“I did not want her to marry him,” he says softly. “I did not trust him, or the fact that five wives had preceded Alyse. But our lady mother was blinded by his title and wealth, and Alyse herself was always eager to keep our mother happy.” His voice trails off, and the silence that follows is so filled with sorrow, I cannot bring myself to break it.

Leaving Beast to his painful memories, I turn my thoughts to our travels. How far west will we need to go to avoid d’Albret’s men? And when should we release the horses with the dead soldiers? I fear we are still too close to the miller and his daughter, and I would not wish the dead to be found anywhere near them.

Even though we cannot see it through the trees, we are drawing near a large stream that, by the sound of it, has swollen to the size of a river with the recent rains. The raging water rushing over the rocks is nearly deafening and I must shout for Beast to hear me. “We must look for a place to cross.”

He nods and we turn our horses in that direction, skirting the thicket until the trees finally thin and we are able to gain passage onto the bank of the stream.

Where soldiers wearing d’Albret’s colors are watering their horses.

Chapter Nineteen

THERE ARE TWELVE MEN ALTOGETHER. Two kneel at the water’s edge, filling their water skins. Another is watering three of the horses, and a fourth is taking a piss by a tree. That is the only thing that saves us with such uneven numbers: that half of them have dismounted and are taking their leisure. That and Beast’s quick reflexes.

Before I have fully registered my surprise, Beast draws his sword and charges into the startled group of men before they can react. He aims straight for the three closest riders. The bank explodes in activity as soldiers scramble for their weapons.

As Beast rides into the fray, my body reacts without conscious thought. I drop my reins and pull my knives from my wrists. The first one strikes one of the mounted soldiers closest to me, catching him in the throat. My second knife takes the next mounted soldier in the eye so that he is thrown backwards just as his horse leaps forward. Some days, like today, my aim and timing is so true it takes my breath away and I feel certain Mortain’s hand guides my own.

As I reach for my crossbow, Beast gives a battle yell that fair curdles my blood. His sword arcs through the air, decapitating one soldier and then slicing a second man near in two on its backstroke. Before Beast can regroup, a third raises his sword, then reels in surprise when a stone from Yannic’s slingshot punches through his teeth, giving Beast time to finish him off.

My crossbow loaded and cocked, I turn to the riders by the stream and pick one off. Two others go for their own crossbows, but not fast enough. The bolt catches one and sends him stumbling into the second man, which gives me time to grab another of my knives and throw it, the silver blade whipping fast and sure across the distance to sink into his eye socket and send him reeling into the stream.

I use the time that buys me to reload my crossbow, but one of the mounted men breaks away from Beast and wheels in my direction before I can get it cocked. I drop the bow and pull the sword from its scabbard, getting it between me and my attacker. “Lady Sybel—” It is only when he hesitates long enough for me to get past his guard and cut off the rest of his words that I realize they have been ordered to take me alive.

Which gives me some small advantage, for I do not care if I kill them. Indeed, I pray that I will.

One of the remaining men is reloading his crossbow, which is aimed right for me. I am out of knives, and Beast is too far away to help. He shouts, drawing the man’s attention, and then I watch open-mouthed as Beast hurls his sword toward him.

I hold my breath as it spins through the air. The hilt catches the soldier full in the face, stunning rather than killing him. But it is enough to give the charging Beast time—he draws his ax, surges forward, and delivers a sickening blow to the soldier’s head. Yannic finishes off the last two of them with well-slung rocks.

The stream’s bank is awash in departing souls, shocking in their chillness, as if winter had suddenly returned. Some rush upward, eager to flee the carnage, even though it can no longer harm them. Others hover, like desolate children, lost, adrift, not sure they understand what has just happened.

It sickens me that I somehow manage to feel sympathy for them. To chase the unwelcome feelings away, I whirl around to rail at Beast. “What in the names of the Nine Saints was that? Throwing your sword? Is that some special trick of Saint Camulos?”

He grins, and I am startled by how feral he looks, all gleaming white teeth and pale eyes in a blood-splattered face. Indeed, I do not believe he is quite human in that moment. “It slowed him down, didn’t it?”

“By mere chance,” I point out. It was the most foolish, jape-fisted bit of buffoonery I have ever seen, and I am impressed in spite of that.

A short while later, as I stare down at the bodies of the six men I have just killed, I cannot help but wonder: Do I love killing? Of a certainty, I love the way my body and weapons move as one; I revel in the knowledge of where to strike for maximum impact. And of a certainty, I am good at it.

But so is Beast. He is perhaps even better at it than I am, and yet for all that, he feels as bright and golden as a lion who roars in the face of his enemies and stalks them in broad daylight.

Whereas I—I am a dark panther, slinking unseen among the shadows, silent and deadly.

But we are both great cats, are we not? And do not even bright things cast a shadow? “Were they waiting for the men at the miller’s?” I ask. “Or are they a separate party of scouts altogether?”

“A separate party, I think. See?” Beast points to a series of hoof prints in the muddy bank where the men had just crossed the stream. “They were on their way back.”

My heart sinks. “Which means they have all the western routes covered. We will have to head due east and approach Rennes from that direction.”

We risk riding into the arms of the French, but at least they will simply kill us and not try to take us back to d’Albret. If the truth be told, I’d rather take my chances with the French.

By the time we stop for the night, Beast is gray with exhaustion and fatigue and hardly able to do more than grunt. As we make camp, it is hard to know which is the greater threat: d’Albret and his be-damned scouts or the blood fever coursing through Beast’s veins. In the end, I decide we must risk a small fire for the poultices, but by the time they are ready, Beast is fast asleep. He does not so much as stir when I place them on his wounds. As I stare down at his still, ugly face, I find myself praying that I will not be left with nothing but his limp, dead body to bring before the duchess.

By some miracle or stubbornness of constitution, Beast is better in the morning. Even so, I insist we travel at an easy pace, well away from the roads. When we stop for a midday break, I almost decide to make camp for the night then and there so Beast can rest, for he is exhausted again, and fresh blood flows from the injury at his thigh. He waves my concerns aside. “It is a good thing, for it will wash the foul humors from the wound.” He insists we keep going, as the farther we get from our pursuers, the better.

Shortly afterward, we draw near the main road to Rennes. Apprehension fills me, for I am certain d’Albret will have it watched, but we must get across. Besides, even d’Albret does not have enough soldiers to man the entire road. Our hope is to find an unguarded section.

We lurk awhile, watching the travelers from our hiding spot in the trees. A farmer carrying hens by a pole across his shoulders goes by, followed by a tinker who clanks and clatters along. Neither of them tarry or linger or appear to be dawdling, so I doubt they are spies. A short while later, a sweat-stained courier races by on a lathered horse, and we can only wonder what news he carries, and to whom.

Since he is not followed—or accosted—we deem it safe to cross. We put our heels to our horses and hurry to the other side before anyone else comes along. Beast catches my eye and flashes me a grin, the first I have seen today, then leads us into the brush and spindly trees on the east side of the road, where we turn north.

I glance over to see how he is faring only to find him watching me. “What?” I ask, uneasy under the weight of that gaze—the man has a way of looking at me as if he can see beneath all the layers of my deception. It is most unsettling.

“One of the soldiers recognized you,” he says.

Merde! With all that was going on, how could he have heard that? “Of course he recognized me,” I scoff, as if he has hay for brains. “I have been in d’Albret’s household for some time. How else do you think I was in a position to rescue you?”

Is it just my imagination or does his face clear somewhat? He frowns as if trying to work out some puzzle. “How did the convent secure you a position in d’Albret’s entourage? By all accounts, he is more suspecting and distrustful than most.”

“The abbess has many political connections among the noble families of Brittany.” I use my most haughty voice in the hopes that it will deter further questions.

It does not look as if it will, for Beast opens his mouth once more, then—praise Mortain!—pauses and cocks his head to the side, an alert look on his face.

“Now what?” I ask.

Beast holds his hand up for us to halt. As I rein in my mount, I hear it: it is not the sound of fighting, exactly, but shouting and men’s voices. “Oh, no,” I whisper at him. “We are not playing at rescue again. You barely have enough strength today to stay in the saddle.”

Ignoring me, he gives some silent command to his horse, who moves forward, winding along a path among the trees and drawing closer to the sounds. Hoping to forestall him, I follow, while Yannic hangs back with the pack animals.

There are five men with horses stopped in front of a farmhouse. Two sit upon their destriers with great, white fluffy bundles in front of them. It takes me a moment to recognize the bundles as sheep. Two of the others are trying frantically to corner a goose, which is doing its best to evade them, honking in irritation all the while. It would be almost comical except for the farmer and his wife standing in the yard held at spear point by the fifth man.

“French,” Beast spits out.

“They do not appear to be harming the farmer or his wife.”

“No, just raiding their food stores to feed their own troops.” He turns to me and smiles. “We will stop them.”

I stare at him in disbelief. “No, we won’t. We cannot pick a fight with every soldier we see between Nantes and Rennes!”

“We cannot just leave these poor people to be bullied by our enemies. Besides”—he shoots his maniacal grin my way—“that will be five French soldiers I will not have to kill later.”

“We cannot risk something happening to you over foodstuffs,” I hiss back.

At an impasse, we stare at each other. Then his horse lifts its leg and steps forward, breaking a small branch under its hoof. A loud crack echoes through the air, and the shouting stops. “Who’s there?” a voice calls out.

I glare at Beast. “You did that on purpose.”

He scowls in mock annoyance. “It was the horse. But now that our presence is known, we have no choice.” He removes the crossbow from its hook on the saddle and pulls three quarrels from the quiver.

I resign myself to our fate and decide to get it over with as quickly as possible. “I must get closer. When I am in place, I will hoot like an owl.”

Now it is Beast’s turn to frown. “I am not sure that is safe.”

I roll my eyes as I dismount. “You are not my nursemaid. Remember, I am rescuing you.” I loop the reins around a nearby branch and begin to move quietly through the trees toward the house.

The leader is ordering one of the goose-chasing men to go in search of the noise they just heard. The woman is wringing her hands and crying about her new down pillow, but I block all of that out as I pick my spot next to a tree that is partially covered by a thick shrub. I pull out my knives and take careful aim at the soldier closest to the farmer and the one most likely to harm him. As I hoot like an owl, I send the first knife flying.

With knives, the two best choices for a kill shot at this distance are the throat or the eye. My aim is perfect and the knife catches him in the throat. The farmwife is made of sturdier stuff than the miller’s daughter, for she does not scream, simply jumps out of the way of the splatter of blood.

My second knife and Beast’s three crossbow bolts make quick work of the rest of them. When they are all dead, the three of us emerge from the trees. The farmer and his wife approach us, their greeting effusive. “Praise be to Matrona! She has sent you to deliver us from certain disaster.”

“Well, you were not in mortal danger,” I point out.

The farmwife bristles at this. “Not in mortal danger? What is starving to death, then, if not mortal danger?”

The farmer glances uneasily at the road. “Do you think more of them are coming?”

Beast follows his gaze. “Not immediately, no. But we’d best get the horses and bodies out of sight.”

“You will do no such thing.” I angle my horse to block his. When he starts to argue, I urge my horse closer and lower my voice. “If you do not have a care for yourself, then at least give a thought to what the duchess and my abbess will do to me if I arrive with nothing but your lifeless body.”

An odd, pained expression crosses his face and I think that at last he understands my peril, if not his. “Besides, it will take all of us working together to get you off that horse and laid down somewhere where I can tend your wounds.”

The farmwife’s hand flies to her cheek. “Was he injured?”

“’Tis an old injury, but a bad one. Is there somewhere we can settle him?”

The farmwife nods. I leave Yannic and the farmer to help Beast from his horse and let the farmwife lead me into the house. As I enter, I look around in surprise, for outside, the farm seemed to me somewhat poor and rundown. Inside, the house is anything but. The farmwife meets my eye. “’Tis not by accident. Living so close to the border, and with so many wars and skirmishes over the years, we have learned to conceal our prosperity. When we are lucky enough to have it.”

She stops at a small storeroom, takes a key from the ring around her waist, and unlocks the door. Two boys spill out, wearing fierce glowers. “Next time let us stay and fight,” one of them says. He is on the cusp of true manhood, all gangly limbs, clumsy feet, and too-large nose.

“Mind your manners and greet our guest.”

For the first time, both of them notice me. Even though I wear three days’ travel grime instead of my finest jewels, their gaping admiration does wonders for my spirits.

The farmwife clucks her tongue. “Go on now, go help your father and the others get rid of the bodies.”

“Bodies?” They perk up, then clatter out of the house.

“My husband is old and no threat to the soldiers, but I could not trust these hotheads not to do something foolish.” The farmwife rolls her eyes, but it does not disguise the pride she feels in her sons.

The farmhouse has a large kitchen and a great room with a long table and benches. While looking for a spot for Beast to rest, I also try to note any exits. We may need to leave suddenly, for there is no guarantee the French will not send others to check on their comrades. And if the French can stumble upon this place, so can d’Albret and his men.

Besides the front door, the three windows with wooden shutters are the only way in and out. And certainly there is no place big enough to conceal Beast.

I nod to the area in front of the hearth. “That will work. The fire will keep him warm and allow me to mix the poultices I need for his leg.”

Her face creases in concern. “How bad is it?”

I meet her intelligent brown-eyed gaze. “Bad enough. If I had any surgeon’s skills, I would consider removing it, but luckily for him, I do not. A prayer or two on his behalf would not go amiss.”

She nods. “This whole family shall pray for him,” she says, and I know I can consider it as good as done.