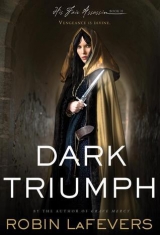

Текст книги "Dark Triumph"

Автор книги: Robin LaFevers

Соавторы: Robin LaFevers

Жанры:

Любовно-фантастические романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-Two

BEAST RAISES HIS DROOPING SWORD, but a curt command from the man with the leather nose stays his hand. He tilts his head up to the branches above us. I follow his gaze and see a dozen archers hidden there, arrows trained upon us. We all eye one another warily.

The leather-nosed man steps forward. He is small and wiry and wears a dark tunic and a leather jerkin over patched breeches. As he moves out of the shadows, I see that he is not as dark-skinned as I had first thought—he is coated with grime. No, not grime. Dust. Or ash, mayhap. As he draws closer still, I see a single acorn hanging from a leather cord around his neck, and then I know. These are the mysterious charbonnerie, the charcoal-burners who live deep in the forests and are rumored to serve the Dark Mother.

With no more noise than a breeze rustling through the leaves, the rest of the charbonnerie emerge from their hiding places. There are twenty of them, counting the archers in the trees. I glance over at Beast. We cannot fight our way out of this one.

With an effort, Beast straightens in his saddle. “We mean you no harm. By right of Saint Cissonius and the grace of Dea Matrona, we wish only to pass the night in the forest.” It is a bold gambit, and a smart one, for while the Dark Matrona is not accepted by the Church, the Nine are her brethren gods, and invoking their blessing cannot hurt.

One of them, a thin fellow with a chin and nose as sharp as blades, spits into the leaves. “Why do you not spend the night at an inn, like most city dwellers?”

“Because there are those who wish us ill, as you just saw.” As Beast speaks, another of the charcoal-burners—a young, gangly fellow who is all elbows and knees—sidles up next to the leader and whispers something in his ear. The leader nods, his gaze sharpening. “Who are you?”

“I am Benebic of Waroch.”

The man who had murmured in the leader’s ear nods in satisfaction, and whispers of the Beast go up around the charcoal-burners. Beast’s exploits have made him famous even among the outcasts.

“And who is it the mighty Beast wishes to avoid?”

“The French,” Beast says. “And those who would support them. At least until I can heal and meet them in a fair fight.”

I hold my breath. The charcoal-burners hate the French as much as most Bretons do, and I can only hope that having a common enemy will give us common cause. One of the older men, the one with a wooden arm, nudges a body with his foot. “These men aren’t French.”

“No, they’re not. But they are traitors to the duchess and wished to detain us.” Then Beast grins one of his savaage grins. “There is plenty of room for you in the war against the French, if you so desire. I would be honored to have such skilled fighters on my side.”

There is a long pause, which makes me think the charbonnerie receive few such invitations.

“What is in it for us?” the sharp-faced man asks, but the leader motions for him to be silent.

Beast smiles. “The pleasure of beating the French.” To him, any fight is its own excuse.

The leader reaches up and scratches his leather nose, suggesting it is a recent replacement. “You can spend the night in the forest, but under our watch. Come. Follow us.” He motions to the others, and a half a dozen of them fall in around us.

They are eerily silent as they guide us deeper into the forest, and our horses’ hooves are muffled by the thick layer of decaying leaves on the ground. The gangly youth cannot keep his eyes off me, and when I catch him staring, he blushes to the roots of his hair.

The trees here are ancient, tall and thick and gnarled like old men bent with age. Even though there are hours of daylight left, little sun gets through the thick tangle of foliage overhead.

At last we reach a large clearing ringed by a half a dozen mounds of earth, each one as big as a small house. Smoke burbles from holes in the mounds, which are tended by nearby men. Interspersed among the mounds are small tents made of stripped branches and stretched hides. Cooking fires are watched over by drably dressed women, while dark, gritty children play close by. When we enter the clearing, everyone stops what they are doing and turns to look at us. The youngest child—a girl—sidles up to her mother and slips her fingers into her mouth.

The leader—Erwan is his name—grunts and points to a section of the clearing far away from the earthen mounds. “Make your camp there.”

All of them watch as Yannic and I dismount, secure our horses, then turn to help Beast off of his.

His breath comes in quick, shallow gasps. “Did you take a new injury?” I ask quietly.

“No.” His grunt is followed by a short bellow of pain. By the time we have him off his horse, the entire camp knows of his condition. Yannic and I are able to steer him but a few feet before he comes to a complete stop. “I think this is a good place to make camp,” he says, then grabs for a nearby tree so he will not crash to the ground.

“Not sure that one is going to live through the night,” the wooden-armed man mumbles, and I glare at him.

The gangly fellow catches my eyes. “Oh, don’t mind Graelon, miss. That’s just his way.” He glances mischievously at the old man, then leans in closer to me. “He was like that before the fire got his arm.” The youth’s charm is infectious.

“I’m Winnog, my lady. At your service.”

“As if she’d have you,” someone mutters.

Ignoring the mutterer, I give Winnog my brightest smile. “Thank you.” As I turn back to Beast’s side, it is all I can do not to clap my hands at the onlookers and cry, Shoo! But they would no doubt consider that a rude repayment of their hospitality, meager as it is.

I sense a movement behind me and feel the beating of a lone heart. Still untrusting of these charbonnerie, I whirl around, hand going to the knife concealed in my crucifix.

The woman I see pauses and casts her eyes down in a gesture of submission. She is dressed in a dark gown, and, like the rest of the women, her hair is wrapped tightly in a coif of some kind. She carries a small sack. “For his wound,” she says. “It will help.”

After a moment, I take the sack from her and peer inside. “What is it?” I ask.

“Ground oak bark to keep infection from setting in. And ashes of burned snakeskin to hasten the healing.”

“What is your name?” I ask.

She glances up at me, then down again. “Malina.”

“Thank you,” I say, and mean it. For I am running out of ideas on how to keep Beast’s wounds from overtaking him before we make it to Rennes.

“Do you need help?” she asks shyly.

While I am certain Beast will hate having his weakness seen by others, it seems prudent to accept any help they offer, an attempt to forge some tenuous bond between us. “Yes, thank you. Do you have any hot water?” She nods, then slips away to fetch it. While she is gone, I quickly sniff the oak bark and the ashes, then put a dab to my tongue to be certain it will do no harm.

“It was not in jest that I invited them to fight with us.” Beast’s voice rumbles up at me. “Did you see how ferocious they were? How unexpected their tactics?” He is as excited as a squire with his first sword. “They could prove valuable allies.”

“If they do not stab us in the back,” I mutter. “Are they not known to be clannish and untrustworthy?”

Beast considers a moment. “Clannish, yes, but that is not the same as being unworthy of trust.”

Malina returns just then, bringing a halt to our conversation. She and I tend Beast’s wounds while he lies back and pretends he is dozing, but his jaw clenches as we work on him. By the time we are done, supper is ready, and, much to my surprise, we are invited to partake of it. It seems we are to be treated as guests rather than prisoners, then. Wishing to capitalize on this, I take one of the cheeses and the two roast chickens that Bette gave us to contribute to the meal.

The charbonneries’ eyes widen with pleasure and the unexpected bounty, and when I sit down to eat, I can see why. Dinner is some sort of mash—acorn, I think. As I take a bite, I cannot help but remember how I called the convent’s food pig slop and how Sister Thomine threatened to force it down my gullet.

A lump forms in my throat, one that has nothing to do with the mash and everything to do with a sense of deep homesickness, for as much as I rebelled against the convent, it was the safest place I have ever lived. I miss Ismae and Annith more than I ever thought possible.

Yannic shovels his gruel into his silent gob steadily, and, beside me, Beast eats with great gusto. “You like it?” I ask softly.

“No. But I do not wish to insult their hospitality.” Since these words are delivered with a pointed look to my own barely touched portion, I turn my attention to eating it while it is still warm.

When dinner is over, the charbonnerie linger around the fire. A few murmur among themselves, but most of them simply stare at us. One of the boys brings out a small wooden flute and begins piping a soft, haunting melody. Erwan leans back against a rock, folds his arms, and studies us in the flickering light. “Tell us of this war with the French,” he says.

Beast takes a sip of whatever spirit it is they have given us. Fermented dew collected from the trees, most likely. “Our young duchess is besieged from within and without. Upon the duchess’s father’s death, the French tried to declare her their ward. Of course, she laughed in their long-nosed faces.” He takes another swig. “But they do not give up, those French. They know that she is young and untried, and as yet unwed. They see our country as ripe for the plucking and are looking for any chance to do just that.”

Erwan appears unmoved. “What is in it for us if we fight?”

“Freedom from French rule,” Beast says simply. But it is clear these cautious men will need more to convince them than that.

“Your way of life,” I add, drawing their eyes to me. “We Bretons at least respect your right to the wildwood. The French will not, and they will claim all the forests and the wood in it as their own. You will be forced to pay dearly for what you now have for free.”

Erwan studies us in silence a moment longer, then barks out a harsh laugh and leans forward to put his arms on his knees. “Freedom, you say? Freedom to scavenge in the forest, reviled by all? Freedom to sell our wares to people who would like to pretend that we do not exist and that their charcoal is left on their doorsteps by some korrigan of hearth tales?”

Beast meets his gaze, unblinking. “The French will not honor your right to the old ways, your right of woodage and coppings. In France, men must pay hard coin for such rights; they do not come to them by birth. And while yours is not an easy life, it was always my understanding that you chose it, chose to follow your god into this exile.”

The other men shift restlessly on their seats and Erwan looks away from Beast to stare deep into the flames. “Choice. That is a funny word. Our father’s father’s father chose for us, did he not? And how long must we live with that choice?” He turns and looks to the pile of sprawling children asleep under their blankets. “And how long must they?” he asks, his voice softening.

“What would you wish different?” I ask.

He looks surprised by the question, but before he can answer, Malina does. “To not have people whisper when we walk by; to not have them make the sign against evil when they think we are not looking; to not be chased from villages or markets when all we wish to do is buy combs for our daughters’ hair or new wheels for our carts.” She looks at me, defiant, her head held high.

“Respect,” I say. “You want respect and to not be reviled.”

Our eyes meet in a moment of perfect understanding, then she nods. “Exactly so.”

“Perhaps if the people saw you take up the duchess’s—and the country’s—cause, they would regard you in a different light,” Beast suggests.

“Most likely not,” the dour Graelon says. “And we’ll have lost our lives for nothing.”

“Every action has some measure of risk,” Beast points out. “You could lose good men simply by doing nothing.” He gestures to those gathered around the fire, with their missing limbs and ruined faces, injuries received while tending the charcoal pits.

“Tell me of the Dark Matrona,” I say softly, giving the truth of Beast’s words time to simmer and do its work. “For I have heard very little of Her.”

Erwan snorts. “That is because the Church does not accept Her.”

Malina takes up the story. “It is said that when Dea Matrona and the rest of the Nine are not strong enough to answer your prayers, it is time to turn to the Dark Mother, for She is a fierce and loving god who especially favors the fallen, the scarred, the wounded, and the castoffs.

“She rules over those places where life rises up out of darkness and decay. The first green shoot in a forest devastated by fire, the pile of dead ash that holds a single red ember, the small creatures that are born in the midden heap.

“Which is why the Church did not invite Her into its fold. The priests saw Her as competition for their Christ and His promise of resurrection.”

Malina reaches up and fondles the acorn at her neck. “The darkest hours of night, just before dawn, belong to Her. The moment when all hope is lost, and yet you dare to hope one more time. That is the power of the Dark Matrona.

“It is She who gave us the gift of coal. Back when we were simple forest dwellers, we grew careless with our fires, and the entire forest went up in flames. For days it burned, killing every tree, every bush, every shrub and blade of grass, until nothing but ash and dust remained. Or so we thought.

“But hidden in those ashes were pieces of wood that had only partially burned and still held the heat of the flames. That charcoal was Her gift to lead us to a new livelihood.”

Malina looks from the flames and meets my eyes. “So of course, we honor Her still, She who provided in our hour of need and gave us hope when it was all but lost.”

In the silence that follows her tale, all that can be heard is the crackle and snap of the burning logs in the fire pit. I cannot say why, but I am moved by this idea that hope—that life—can spring from darkness and decay. It is not something I’ve considered before. “What if this is another chance She is holding before you?” I ask.

Malina blinks in surprise.

“You have given up hope of gaining respect or fellowship, and yet here we are, offering you just such a chance.”

Beast leans forward. “We can do little to sway the Church, but the people can be swayed, and they often embrace things the Church wishes they would not. And so I ask you: Will you join us?”

Their gazes hold across the fire—Beast’s challenging, yet inviting. Erwan’s doubting and full of questions. Before either of them speaks, Malina says, “Let us consult with Brother Oak.”

There is a murmur of consensus among the charbonnerie, then an ancient man creaks to his feet and draws near the fire. His gnarled, trembling hands untie a pouch at his waist and he extracts a big, misshapen brown lump. At first I think it is an enormous dark mushroom, but when he draws closer to the fire, I can see it is an oak gall.

The old man places it carefully on one of the rocks that circle the fire, then removes a small ax that hangs from his waist. He closes his eyes and holds the ax over the fire, his lips murmuring in some old language I do not understand. The rest of the charbonnerie murmur with him. When they stop their murmuring, the old man takes the ax and, with surprising strength, brings it down to break open the oak gall. Because I am close, I can see a small white grub wiggling in the wreckage. After a moment, the grub spreads its wings—no grub, then—and flies.

The old man looks up to the waiting charbonnerie. “The Dark Mother says we fight.”

And so it is settled.

We ride out at dawn’s light, accompanied by a full cadre of charbonnerie. As luck would have it, they have a load of charcoal to bring to a blacksmith in Rennes. I have disguised myself as one of their women, and Beast sits in the back of one of the carts and plays the simpleton. Yannic fits right in.

Not even d’Albret, with all his suspicion and distrust, would think to look for us here.

Chapter Twenty-Three

FOR ALL HIS EARLIER PROTESTS that he would be pummeled to pulp if he rode in a wagon, Beast sleeps the entire way to Rennes laid out in the back of one of the charbonnerie’s three carts. Twice d’Albret’s scouts pass us on the road, and both times they scarcely glance at the charbonnerie, let alone think to look for us among them. And best of all, by the time we come in sight of the city walls, Beast is better, whether due to all the rest or to the herbs Malina provided, I am not sure.

The cathedral bells are ringing out the call to late-afternoon prayers as we approach the city gate. Although I do not know all of d’Albret’s men by sight, I study the sentries and everyone in the crowd at the city gates. I ignore the slouching of the peasant and the confident stride of the city guard; I stare past the clothes they wear and study their faces, for if I can don a disguise, so can they.

I cannot believe we have done the impossible. Not only have we escaped d’Albret, but we have evaded recapture as well, and that is hard to wrap my mind around.

Beast point-blank refuses to be hauled into the city with a load of charcoal, so we pause long enough to get him up on a horse. A hum of urgency buzzes in my head like a swarm of gnats, and there is an itching between my shoulder blades that is nearly unbearable. Four men and much grunting later, the great lummox is astride his mount. Soon, I promise myself. Soon he will no longer be my responsibility but someone else’s—someone far more capable than I. The thought does not cheer me as much as it once did.

As our small group makes ready to approach the gates, I try not to fidget. We are heavily covered in black dust from the charcoal-burners and their wares, which aids our disguise somewhat, but nothing can disguise Beast’s size or bearing. “Slouch a bit,” I tell him.

He looks at me quizzically, but honors my request, bringing his shoulders forward and bowing his spine so that he slumps in his saddle. “Why?” he asks.

“You are difficult to hide, and the longer we keep your arrival secret, the better. It would be wise to prevent d’Albret and his forces from knowing we are in Rennes for as long as possible.”

And then we are at the gatehouse. Erwan informs the soldiers of his charcoal deliveries and is waved through. One of the soldiers eyes Beast warily, but the truth is, between the knight’s time on the road and his stay in the dungeon, not to mention the grievous injuries he still bears, it is not difficult for him to look like a giant simpleton.

I breathe a hearty sigh of relief once we are inside the city. Indeed, every one of my muscles seems to unclench now that there are twelve-foot-thick walls, twenty leagues, and an entire city garrison between us and d’Albret.

Much like my own mood, the city’s borders on jubilant, drunk on its own importance of being the duchess’s place of refuge, just as I am nearly drunk with the thrill of completing my mission. But there is caution here as well, in the way the people going about their business glance at newcomers, assessing.

We stay with the charcoal-burners as long as possible, passing by the tannery conducting its foul-smelling business down by the river, then turning up the street that leads to the section of town where the smiths can be found. They consume enough coal in their furnaces to keep the charbonnerie in pottage for the entire winter. We bid the charbonnerie goodbye, and Beast promises to send word when he has spoken to the duchess and her advisors of his plan to use the charcoal-burners against the French.

As he and I begin making our way toward the nicer part of town, I unwind the distinctive charbonnerie coif from my head and comb my fingers through my hair, then take the shawl from my shoulders. I use a clean corner of it to wipe the charcoal dust from my face so I am no longer one of the despised charbonnerie but merely a comely—if grubby—serving maid.

By the time we reach the palace, dusk is falling, and the sentries are just lighting the torches. It is not like Guérande, where people came and went as they pleased. The guards at the door speak with everyone who wishes to enter. “That’s new,” Beast says.

“At least someone has an eye toward the duchess’s safety.” It is one more barrier between d’Albret’s spies and the duchess, and it will give them pause if they must stop and present themselves. “However, the guards will likely not grant us an audience with the duchess when we look like this, at least not without a full explanation of who we are, and I do not wish to announce your arrival to these men.”

Beast pauses in wiping the charcoal dust from his face. “You don’t trust them?”

“It is more accurate to say that I don’t trust anyone. I wonder if Ismae is still assigned to the duchess. Perhaps I can get a message to her.”

Beast glances at the sentries. “I am not sure they would grant you an audience with Ismae even if she is here.”

I grimace, for he is most likely correct.

Beast thinks a moment, then reaches into some hidden pouch tucked on his person and removes something. “Here.” He hands me a small brooch—the silver oak leaves of Saint Camulos. “Ismae should recognize this, and if she does not, Captain Dunois will. As will the guards. They will honor any who carries this symbol.”

Holding the brooch tightly in my hand, I dismount, leaving him and Yannic to stay with the horses. I approach the palace and wait for the guard to finish questioning a burgher who is there to meet with the chancellor and complain about the most recent round of taxes. After the burgher has been told the chancellor has much more important business at hand—such as keeping the city from being attacked by the French—he is sent on his way, and then I am facing the sentry. He scowls at my poor clothing and the grime I am covered in. Even so, I tilt my head and give him my most fetching smile. He blinks, and his scowl softens. “What do you want?” he asks. “If you’re looking for scullery work, you must go around to the kitchens.”

I glance at the handful of pages lingering just inside the door. “I wish to get a message to one of the duchess’s attendants.”

The second sentry saunters over. “What business could you have with one of the duchess’s ladies in waiting?” he asks, as if the mere idea is some great jest.

I decide that a little mystery will aid my cause. “Ismae Rienne is no mere lady in waiting,” I tell him. “Give her this and bid her come as quickly as she can.”

I do not know if it is the mention of Ismae or the sight of Beast’s silver oak leaves that catches the guard’s attention. Whichever it is, he takes the brooch, hands it to a page, and murmurs some instructions. When the boy scampers off, I saunter over to wait by the wall, trying to look important but harmless—a surprisingly difficult combination. After a few moments, the sentry decides I won’t dash in on my own, so relaxes his guard somewhat.

I rest my head against the stone and allow the sense of jubilation to flow through me. Beast is still alive and we are as safe here as anywhere in the entire kingdom. With the abbess tucked away at the convent on the other side of the country, she will not know that I have arrived in Rennes until she receives a message. She cannot send me on a new assignment. At least not for a while. That gives me some time to work out what I would like to do next. Suddenly, the world looms large, full of possibilities and freedom.

And no one—no one—here in Rennes knows my true identity, so my secrets will be safe.

At the faint murmur of approaching voices, I carefully tuck my moment of triumph away and inch toward the causeway.

“No, you cannot kill him. He is the duchess’s own cousin,” a man’s voice points out wryly.

“All the more reason not to trust him,” a woman says.

It is Ismae, and the joy and relief I feel at hearing her voice is nearly overwhelming.

“If something should happen to the duchess,” she continues, “he stands to inherit the kingdom. Besides, he has been a guest of the French regent for the last year. How do we know where his true allegiance lies?”

“He was a prisoner!” The man’s exasperation is nearly palpable.

When Ismae speaks again, she sounds aggrieved. “Why did you not stay with the council? The message was for me, not you.” Unable to stop myself, I smile. For it is such a very Ismae-like thing to say.

“Because the message was the sigil of Saint Camulos, whom I serve, not you.”

Then she and the gentleman emerge from the entryway and hurry toward the sentry. “Where did you get this?” the nobleman demands. He is tall, with dark hair and the well-muscled grace of a soldier.

The guard points to me. The man’s head snaps around and I am speared by a gray gaze that is as cold and hard as the stone at my back.

He takes a step in my direction. “Who are you?” he asks in a low, angry voice.

Before I can answer, Ismae shoves him aside. “The message was for me, Duval. Oh! Sybella!” Then she throws herself at me and I am encased in a fierce hug. I hug her back, surprised at how very much I want to weep into her shoulder. She is alive. And she is here. For a long moment, that is enough, and I simply savor the feel of her familiar arms about me.

She pulls away to eye me carefully. “Is it really you?”

I smile, although I can tell it is a lopsided effort. “In the flesh.”

“The oak leaves?” The nobleman’s impatience rolls off him in waves as he clenches the silver brooch in his hand. Duval, Ismae called him, which means he is the bastard brother of the duchess.

“I have brought you something,” I tell them. “There.” I nod to where Beast and Yannic wait on their horses.

Duval’s face lights up just as Ismae’s did when she saw me, but before he can hurry to him, I grab his arm. “He is gravely injured. Once you get him off that horse, you will need men and a litter to move him. And you must do it quietly. I bring much news and none of it good.”

Duval frowns his understanding and gives the guards an order to send for help—and to keep quiet about it—then rushes off to greet his friend.

“You did it!” Ismae whispers fiercely. “You got him free. I knew you could.”

I stare at her. “You knew of my orders?”

She grabs my hands. “It was my idea! The only way I could think of to get you out of there. Every time I saw you in Guérande, I feared for your safety and your sanity. Now here you are, and that haunted, mad glint is gone from your eyes.”

I do not know whether to kiss her for getting me out of d’Albret’s household or slap her for all the trouble her idea has caused me. In any case, her words ring true. I no longer feel as if I dance along the edge of madness.

Ismae puts her arm though mine, and we begin walking toward the others. “I will never forgive the reverend mother for assigning you to d’Albret. She might as well have sent you into the Underworld itself.”

A faint wave of panic threatens, then recedes. Ismae does not know—has never known—my true identity, for all that we are like sisters. I am saved from further conversation when I hear Beast bellow, “Saint’s teeth! You’re alive? How is that possible?”

It is Duval who answers. “By the same batch of miracles that has you astride that horse, you great ox.”

Then Ismae and I must jump aside as a half a dozen men come trotting by bearing an empty litter. Ismae points them toward Duval and Beast. “Come,” I say. I let go of her arm and hurry after the litter. “I must give them instructions as to Beast’s care.”

Over Beast’s loud protestations that he is fine, I warn Duval that, in addition to having a fever, Beast cannot put any weight on his leg.

Duval and the men have a quick conference among themselves. “We will take him to the convent run by the sisters of Saint Brigantia. If anyone can tend his injuries, it will be them.” He shoots me a look that lets me know he will be wanting answers soon, then he directs his men to help Beast.

But it is no easy thing to remove an injured twenty-stone man from his horse, and it cannot be done without some jostling and bumping. Beast grits his teeth, and his face turns white as he mutters something about being tossed around like a sack of onions. Then one of the men loses his grip, and the horse startles, slamming Beast’s wounded leg between its flank and the helping guard, and Beast faints.

I sigh. “I fear that has become a new habit of his,” I murmur to the others. “Although it is probably for the better.” I motion for Yannic to dismount so he and I can show the damn-fool soldiers how to get Beast off the horse without killing him.

It is clear that Duval is torn between concern for his friend and his duty to his sister. In the end, I assure him that Yannic is as able as any of us to see to Beast’s care, so he gives stern instructions to the men on what to tell the sisters of Saint Brigantia, with promises that he will be there shortly. Then he turns to me. “Come now. We would hear your accounting of what has happened.”

“But of course, my lord.” Indeed, I cannot wait to discharge what I know. It is as if I have been carrying a hot ember deep inside my body that is slowly turning my insides to ash. It will be no hardship to be rid of that burden.

Ismae loops her arm through mine as we follow Duval to the palace door. “Where is he taking us?” I ask under my breath.

“To the duchess’s chamber, where she is holding council with her advisors.”

“At this hour?”

Ismae grows sober. “At all hours, I’m afraid.”

“Are they trustworthy, these advisors of hers?” I have not been impressed with the steadfastness of her guardians Marshal Rieux and Madame Dinan.

She grimaces. “Yes, that is why it is such a small group.”

As Duval leads us through the maze of palace halls and corridors, I allow myself to adjust to the cacophony of the beating hearts and hammering pulses. It is as if a hundred minstrels have all decided to bang their drums at the same time.

I also study the faces of the people I pass—servants, retainers, even the pages—trying to get a sense of their characters.