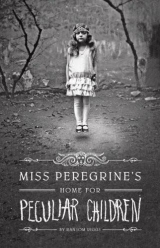

Текст книги "Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children"

Автор книги: Ransom Riggs

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

I took up the rear, trying to figure out what I would say to Miss Peregrine when I met her. I was expecting to be introduced to a proper Welsh lady and sip tea in the parlor and make polite small talk until the time seemed right to break the bad news. I’m Abraham Portman’s grandson, I would say. I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this, but he’s been taken from us. Then, once she’d finished quietly dabbing away tears, I would ply her with questions.

I followed Dylan and Worm along a path that wound through pastures of grazing sheep before a lung-busting ascent up a ridge. At the top hovered an embankment of rolling, snaking fog so dense it was like stepping into another world. It was truly biblical; a fog I could imagine God, in one of his lesser wraths, cursing the Egyptians with. As we descended the other side it only seemed to thicken. The sun faded to a pale white bloom. Moisture clung to everything, beading on my skin and dampening my clothes. The temperature dropped. I lost Worm and Dylan for a moment and then the path flattened and I came upon them just standing, waiting for me.

“Yank boy!” Dylan called. “This way!”

I followed obediently. We abandoned the path to plow through a field of marshy grass. Sheep stared at us with big leaky eyes, their wool soggy and tails drooping. A small house appeared out of the mist. It was all boarded up.

“You sure this is it?” I said. “It looks empty.”

“Empty? No way, there’s loads of shit in there,” Worm replied.

“Go on,” said Dylan. “Have a look.”

I had a feeling it was a trick but stepped up to the door and knocked anyway. It was unlatched and opened a little at my touch. It was too dark to see inside, so I took a step through—and, to my surprise, down—into what looked like a dirt floor but, I quickly realized, was in fact a shin-deep ocean of excrement. This tenantless hovel, so innocent looking from the outside, was really a makeshift sheep stable. Quite literally a shithole.

“Oh my God!” I squealed in disgust.

Peals of laughter exploded from outside. I stumbled backward through the door before the smell could knock me unconscious and found the boys doubled over, holding their stomachs.

“You guys are assholes,” I said, stomping the muck off my boots.

“Why?” said Worm. “We told you it was full of shit!”

I got in Dylan’s face. “Are you gonna show me the house or not?”

“He’s serious,” said Worm, wiping tears from his eyes.

“Of course I’m serious!”

Dylan’s smile faded. “I thought you were taking a piss, mate.”

“Taking a what?”

“Joking, like.”

“Well, I wasn’t.”

The boys exchanged an uneasy look. Dylan whispered something to Worm. Worm whispered something back. Finally Dylan turned and pointed up the path. “If you really want to see it,” he said, “keep going past the bog and through the woods. It’s a big old place. You can’t miss it.”

“What the hell. You’re supposed to go with me!”

Worm looked away and said, “This is as far as we go.”

“Why?”

“It just is.” And they turned and began to trudge back the way we’d come, receding into the fog.

I weighed my options. I could tuck tail and follow my tormenters back to town, or I could go ahead alone and lie to Dad about it.

After four seconds of intense deliberation, I was on my way.

* * *

A vast, lunar bog stretched away into the mist from either side of the path, just brown grass and tea-colored water as far as I could see, featureless but for the occasional mound of piled-up stones. It ended abruptly at a forest of skeletal trees, branches spindling up like the tips of wet paintbrushes, and for a while the path became so lost beneath fallen trunks and carpets of ivy that navigating it was a matter of faith. I wondered how an elderly person like Miss Peregrine would ever be able to negotiate such an obstacle course. She must get deliveries, I thought, though the path looked like it hadn’t seen a footprint in months, if not years.

I scrambled over a giant trunk slick with moss, and the path took a sharp turn. The trees parted like a curtain and suddenly there it was, cloaked in fog, looming atop a weed-choked hill. The house. I understood at once why the boys had refused to come.

My grandfather had described it a hundred times, but in his stories the house was always a bright, happy place—big and rambling, yes, but full of light and laughter. What stood before me now was no refuge from monsters but a monster itself, staring down from its perch on the hill with vacant hunger. Trees burst forth from broken windows and skins of scabrous vine gnawed at the walls like antibodies attacking a virus—as if nature itself had waged war against it—but the house seemed unkillable, resolutely upright despite the wrongness of its angles and the jagged teeth of sky visible through sections of collapsed roof.

I tried to convince myself that it was possible someone could still live there, run-down as it was. Such things weren’t unheard of where I came from—a falling-down wreck on the edge of town, curtains permanently drawn, that would turn out to have been home to some ancient recluse who’d been surviving on ramen and toenail clippings since time immemorial, though no one realizes it until a property appraiser or an overly ambitious census taker barges in to find the poor soul returning to dust in a La-Z-Boy. People get too old to care for a place, their family writes them off for one reason or another—it’s sad, but it happens. Which meant, like it or not, that I was going to have to knock.

I gathered what scrawny courage I had and waded through waist-high weeds to the porch, all broken tile and rotting wood, to peek through a cracked window. All I could make out through the smeared glass were the outlines of furniture, so I knocked on the door and stood back to wait in the eerie silence, tracing the shape of Miss Peregrine’s letter in my pocket. I’d taken it along in case I needed to prove who I was, but as a minute ticked by, then two, it seemed less and less likely that I would need it.

Climbing down into the yard, I circled the house looking for another way in, taking the measure of the place, but it seemed almost without measure, as though with every corner I turned the house sprouted new balconies and turrets and chimneys. Then I came around back and saw my opportunity: a doorless doorway, bearded with vines, gaping and black; an open mouth just waiting to swallow me. Just looking at it made my skin crawl, but I hadn’t come halfway around the world just to run away screaming at the sight of a scary house. I thought of all the horrors Grandpa Portman had faced in his life, and felt my resolve harden. If there was anyone to find inside, I would find them. I mounted the crumbling steps and crossed the threshold.

* * *

Standing in a tomb-dark hallway just inside the door, I stared frozenly at what looked for all the world like skins hanging from hooks. After a queasy moment in which I imagined some twisted cannibal leaping from the shadows with knife in hand, I realized they were only coats rotted to rags and green with age. I shuddered involuntarily and took a deep breath. I’d only explored ten feet of the house and was already about to foul my underwear. Keep it together, I told myself, and then slowly moved forward, heart hammering in my chest.

Each room was a disaster more incredible than the last. Newspapers gathered in drifts. Scattered toys, evidence of children long gone, lay skinned in dust. Creeping mold had turned window-adjacent walls black and furry. Fireplaces were throttled with vines that had descended from the roof and begun to spread across the floors like alien tentacles. The kitchen was a science experiment gone terribly wrong—entire shelves of jarred food had exploded from sixty seasons of freezing and thawing, splattering the wall with evil-looking stains—and fallen plaster lay so thickly over the dining room floor that for a moment I thought it had snowed indoors. At the end of a light-starved corridor I tested my weight on a rickety staircase, my boots leaving fresh tracks in layers of dust. The steps groaned as if woken from a long sleep. If anyone was upstairs, they’d been there a very long time.

Finally I came upon a pair of rooms missing entire walls, into which a little forest of underbrush and stunted trees had grown. I stood in the sudden breeze wondering what could possibly have done that kind of damage, and began to get the feeling that something terrible had happened here. I couldn’t square my grandfather’s idyllic stories with this nightmare house, nor the idea that he’d found refuge here with the sense of disaster that pervaded it. There was more left to explore, but suddenly it seemed like a waste of time; it was impossible that anyone could still be living here, even the most misanthropic recluse. I left the house feeling like I was further than ever from the truth.

Chapter Four

Once I’d hopped and tripped and felt my way like a blind man through the woods and fog and reemerged into the world of sun and light, I was surprised to find the sun sinking and the light going red. Somehow the whole day had slipped away. At the pub my dad was waiting for me, a black-as-night beer and his open laptop on the table in front of him. I sat down and swiped his beer before he’d had a chance to even look up from typing.

“Oh, my sweet lord,” I sputtered, choking down a mouthful, “what is this? Fermented motor oil?”

“Just about,” he said, laughing, and then snatched it back. “It’s not like American beer. Not that you’d know what that tastes like, right?”

“Absolutely not,” I said with a wink, even though it was true. My dad liked to believe I was as popular and adventuresome as he was at my age—a myth it had always seemed easiest to perpetuate.

I underwent a brief interrogation about how I’d gotten to the house and who had taken me there, and because the easiest kind of lying is when you leave things out of a story rather than make them up, I passed with flying colors. I conveniently forgot to mention that Worm and Dylan had tricked me into wading through sheep excrement and then bailed out a half-mile from our destination. Dad seemed pleased that I’d already managed to meet a couple kids my own age; I guess I also forgot to mention the part about them hating me.

“So how was the house?”

“Trashed.”

He winced. “Guess it’s been a long time since your Grandpa lived there, huh?”

“Yeah. Or anyone.”

He closed the laptop, a sure sign I was about to receive his full attention. “I can see you’re disappointed.”

“Well, I didn’t come thousands of miles looking for a house full of creepy garbage.”

“So what’re you going to do?”

“Find people to talk to. Someone will know what happened to the kids who used to live there. I figure a few of them must still be alive, on the mainland if not around here. In a nursing home or something.”

“Sure. That’s an idea.” He didn’t sound convinced, though. There was an odd pause, and then he said, “So do you feel like you’re starting to get a better handle on who your grandpa was, being here?”

I thought about it. “I don’t know. I guess so. It’s just an island, you know?”

He nodded. “Exactly.”

“What about you?”

“Me?” He shrugged. “I gave up trying to understand my father a long time ago.”

“That’s sad. Weren’t you interested?”

“Sure I was. Then, after a while, I wasn’t anymore.”

I could feel the conversation going in a direction I wasn’t entirely comfortable with, but I persisted anyway. “Why not?”

“When someone won’t let you in, eventually you stop knocking. Know what I mean?”

He hardly ever talked like this. Maybe it was the beer, or that we were so far from home, or maybe he’d decided I was finally old enough to hear this stuff. Whatever the reason, I didn’t want him to stop.

“But he was your dad. How could you just give up?”

“It wasn’t me who gave up!” he said a little too loudly, then looked down, embarrassed and swirled the beer in his glass. “It’s just that—the truth is, I think your grandpa didn’t know how to be a dad, but he felt like he had to be one anyway, because none of his brothers or sisters survived the war. So he dealt with it by being gone all the time—on hunting trips, business trips, you name it. And even when he was around, it was like he wasn’t.”

“Is this about that one Halloween?”

“What are you talking about?”

“You know—from the picture.”

It was an old story, and it went like this: It was Halloween. My dad was four or five years old and had never been trick-or-treating, and Grandpa Portman had promised to take him when he got off work. My grandmother had bought my dad this ridiculous pink bunny costume, and he put it on and sat by the driveway waiting for Grandpa Portman to come home from five o’clock until nightfall, but he never did. Grandma was so mad that she took a picture of my dad crying in the street just so she could show my grandfather what a huge asshole he was. Needless to say, that picture has long been an object of legend among members of my family, and a great embarrassment to my father.

“It was a lot more than just one Halloween,” he grumbled. “Really, Jake, you were closer to him than I ever was. I don’t know—there was just something unspoken between the two of you.”

I didn’t know how to respond. Was he jealous of me?

“Why are you telling me this?”

“Because you’re my son, and I don’t want you to get hurt.”

“Hurt how?”

He paused. Outside the clouds shifted, the last rays of daylight throwing our shadows against the wall. I got a sick feeling in my stomach, like when your parents are about to tell you they’re splitting up, but you know it before they even open their mouths.

“I never dug too deep with your grandpa because I was afraid of what I’d find,” he said finally.

“You mean about the war?”

“No. Your grandpa kept those secrets because they were painful. I understood that. I mean about the traveling, him being gone all the time. What he was really doing. I think—your aunt and I both thought—that there was another woman. Maybe more than one.”

I let it hang between us for a moment. My face tingled strangely. “That’s crazy, Dad.”

“We found a letter once. It was from a woman whose name we didn’t know, addressed to your grandfather. I love you, I miss you, when are you coming back, that kind of thing. Seedy, lipstick-on-the-collar type stuff. I’ll never forget it.”

I felt a hot stab of shame, like somehow it was my own crime he was describing. And yet I couldn’t quite believe it.

“We tore up the letter and flushed it down the toilet. Never found another one, either. Guess he was more careful after that.”

I didn’t know what to say. I couldn’t look at my father.

“I’m sorry, Jake. This must be hard to hear. I know how much you worshipped him.” He reached out to squeeze my shoulder but I shrugged him off, then scraped back my chair and stood up.

“I don’t worship anyone.”

“Okay. I just ... I didn’t want you to be surprised, that’s all.”

I grabbed my jacket and slung it over my shoulder.

“What are you doing? Dinner’s on the way.”

“You’re wrong about him,” I said. “And I’m going to prove it.”

He sighed. It was a letting-go kind of sigh. “Okay. I hope you do.”

I slammed out of the Priest Hole and started walking, heading nowhere in particular. Sometimes you just need to go through a door.

It was true, of course, what my dad had said: I did worship my grandfather. There were things about him that I needed to be true, and his being an adulterer was not one of them. When I was a kid, Grandpa Portman’s fantastic stories meant it was possible to live a magical life. Even after I stopped believing them, there was still something magical about my grandfather. To have endured all the horrors he did, to have seen the worst of humanity and have your life made unrecognizable by it, to come out of all that the honorable and good and brave person I knew him to be—that was magical. So I couldn’t believe he was a liar and a cheater and a bad father. Because if Grandpa Portman wasn’t honorable and good, I wasn’t sure anyone could be.

* * *

The museum’s doors were open and its lights were on, but no one seemed to be inside. I’d gone there to find the curator, hoping he knew a thing or two about the island’s history and people, and could shed some light on the empty house and the whereabouts of its former inhabitants. Figuring he’d just stepped out for a minute—the crowds weren’t exactly kicking down his door—I wandered into the sanctuary to kill time checking out museum displays.

The exhibits, such as they were, were arranged in big open-fronted cabinets that lined the walls and stood where pews had once been. For the most part they were unspeakably boring, all about life in a traditional fishing village and the enduring mysteries of animal husbandry, but one exhibit stood out from the rest. It was in a place of honor at the front of the room, in a fancy case that rested atop what had been the altar. It lived behind a rope I stepped over and a little warning sign I didn’t bother to read, and its case had polished wooden sides and a Plexiglas top so that you could only see into it from above.

When I looked inside, I think I actually gasped—and for one panicky second thought monster!—because I had suddenly and unexpectedly come face-to-face with a blackened corpse. Its shrunken body bore an uncanny resemblance to the creatures that had haunted my dreams, as did the color of its flesh, which was like something that had been spit-roasted over a flame. But when the body failed to come alive and scar my mind forever by breaking the glass and going for my jugular, my initial panic subsided. It was just a museum display, albeit an excessively morbid one.

“I see you’ve met the old man!” called a voice from behind me, and I turned to see the curator striding in my direction. “You handled it pretty well. I’ve seen grown men faint dead away!” He grinned and reached out to shake my hand. “Martin Pagett. Don’t believe I caught your name the other day.”

“Jacob Portman,” I said. “Who’s this, Wales’s most famous murder victim?”

“Ha! Well, he might be that, too, though I never thought of him that way. He’s our island’s senior-most resident, better known in archaeological circles as Cairnholm Man—though to us he’s just the Old Man. More than twenty-seven hundred years old, to be exact, though he was only sixteen when he died. So he’s rather a young old man, really.”

“Twenty-seven hundred?” I said, glancing at the dead boy’s face, his delicate features somehow perfectly preserved. “But he looks so ...”

“That’s what happens when you spend your golden years in a place where oxygen and bacteria can’t exist, like the underside of our bog. It’s a regular fountain of youth down there—provided you’re already dead, that is.”

“That’s where you found him? The bog?”

He laughed. “Not me! Turf cutters did, digging for peat by the big stone cairn out there, back in the seventies. He looked so fresh they thought there might be a killer loose on Cairnholm—till the cops had a look at the Stone Age bow in his hand and the noose of human hair round his neck. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

I shuddered. “Sounds like a human sacrifice or something.”

“Exactly. He was done in by a combination of strangulation, drowning, disembowelment, and a blow to the head. Seems rather like overkill, don’t you think?”

“I guess so.”

Martin roared with laughter. “He guesses so!”

“Okay, yeah, it does.”

“Sure it does. But the really fascinating thing, to us modern folk, anyway, is that in all likelihood the boy went to his death willingly. Eagerly, even. His people believed that bogs—and our bog in particular—were entrances to the world of the gods, and so the perfect place to offer up their most precious gift: themselves.”

“That’s insane.”

“I suppose. Though I imagine we’re killing ourselves right now in all manner of ways that’ll seem insane to people in the future. And as doors to the next world go, a bog ain’t a bad choice. It’s not quite water and it’s not quite land—it’s an in-between place.” He bent over the case, studying the figure inside. “Ain’t he beautiful?”

I looked at the body again, throttled and flayed and drowned and somehow made immortal in the process.

“I don’t think so,” I said.

Martin straightened, then began to speak in a grandiose tone. “Come, you, and gaze upon the tar man! Blackly he reposes, tender face the color of soot, withered limbs like veins of coal, feet lumps of driftwood hung with shriveled grapes!” He threw his arms out like a hammy stage actor and began to strut around the case. “Come, you, and bear witness to the cruel art of his wounds! Purled and meandering lines drawn by knives; brain and bone exposed by stones; the rope still digging at his throat. First fruit slashed and dumped – seeker of Heaven – old man arrested in youth – I almost love you!”

He took a theatrical bow as I applauded. “Wow,” I said, “did you write that?”

“Guilty!” he replied with a sheepish smile. “I twiddle about with lines of verse now and then, but it’s only a hobby. In any case, thank you for indulging me.”

I wondered what this odd, well-spoken man was doing on Cairnholm, with his pleated slacks and half-baked poems, looking more like a bank manager than someone who lived on a windswept island with one phone and no paved roads.

“Now, I’d be happy to show you the rest of my collection,” he said, escorting me toward the door, “but I’m afraid it’s shutting-up time. If you’d like to come back tomorrow, however—”

“Actually, I was hoping you might know something,” I said, stopping him before he could shoo me out. “It’s about the house I mentioned this morning. I went to see it.”

“Well!” he exclaimed. “I thought I’d scared you off it. How’s our haunted mansion faring these days? Still standing?”

I assured him that it was, then got right to the point. “The people that lived there—do you have any idea what happened to them?”

“They’re dead,” he replied. “Happened a long time ago.”

I was surprised—though I probably shouldn’t have been. Miss Peregrine was old. Old people die. But that didn’t mean my search was over. “I’m looking for anyone else who might have lived there, too, not just the headmistress.”

“All dead,” he repeated. “No one’s lived there since the war.”

That took me a moment to process. “What do you mean? What war?”

“When we say ‘the war’ around here, my boy, there’s only one that we mean—the second. It was a German air raid that got ’em, if I’m not mistaken.”

“No, that can’t be right.”

He nodded. “In those days, there was an anti-aircraft gun battery at the far tip of the island, past the wood where the house is. It made Cairnholm a legitimate military target. Not that ‘legitimate’ mattered much to the Germans one way or another, mind you. Anyway, one of the bombs went off track, and, well ...” He shook his head. “Nasty luck.”

“That can’t be right,” I said again, though I was starting to wonder.

“Why don’t you sit down and let me fix you some tea?” he said. “You look a bit off the mark.”

“Just feeling a little light-headed ...”

He led me to a chair in his office and went to make the tea. I tried to collect my thoughts. Bombed in the war—that would certainly explain those rooms with blown-out walls. But what about the letter from Miss Peregrine—postmarked Cairnholm—sent just fifteen years ago?

Martin returned, handing me a mug. “There’s a nip of Penderyn in it,” he said. “Secret recipe, you know. Should get you sorted in no time.”

I thanked him and took a sip, realizing too late that the secret ingredient was high-test whiskey. It felt like napalm flushing down my esophagus. “It does have a certain kick,” I admitted, my face going red.

He frowned. “Reckon I ought to fetch your father.”

“No, no, I’ll be fine. But if there’s anything else you can tell me about the attack, I’d be grateful.”

Martin settled into a chair opposite me. “About that, I’m curious. You say your grandfather lived here. He never mentioned it?”

“I’m curious about that, too,” I said. “I guess it must’ve been after his time. Did it happen late in the war or early?”

“I’m ashamed to admit I don’t know. But if you’re keen, I can introduce you to someone who does—my Uncle Oggie. He’s eighty-three, lived here his whole life. Still sharp as a tack.” Martin glanced at his watch. “If we catch him before Father Ted comes on the telly, I’m sure he’d be more than happy to tell you anything you like.”

* * *

Ten minutes later Martin and I were wedged deep in an overstuffed sofa in Oggie’s living room, which was piled high with books and boxes of worn-out shoes and enough lamps to light up Carlsbad Caverns, all but one of them unplugged. Living on a remote island, I was starting to realize, turned people into pack rats. Oggie sat facing us in a threadbare blazer and pajama bottoms, as if he’d been expecting company—just not pants-worthy company—and rocked endlessly in a plastic-covered easy chair as he talked. He seemed happy just to have an audience, and after he’d gone on at length about the weather and Welsh politics and the sorry state of today’s youth, Martin was finally able to steer him around to the attack and the children from the home.

“Sure, I remember them,” he said. “Odd collection of people. We’d see them in town now and again—the children, sometimes their minder-woman, too—buying milk and medicine and what-have-you. You’d say ‘good morning’ and they’d look the other way. Kept to themselves, they did, off in that big house. Lot of talk about what might’ve been going on over there, though no one knew for sure.”

“What kind of talk?”

“Lot of rot. Like I said, no one knew. All I can say is they weren’t your regular sort of orphan children—not like them Barnardo Home kids they got in other places, who you’ll see come into town for parades and things and always have time for a chat. This lot was different. Some of ’em couldn’t even speak the King’s English. Or any English, for that matter.”

“Because they weren’t really orphans,” I said. “They were refugees from other countries. Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia ...”

“Is that what they were, now?” Oggie said, cocking an eyebrow at me. “Funny, I hadn’t heard that.” He seemed offended, like I’d insulted him by pretending to know more about his island than he did. His chair-rocking got faster, more aggressive. If this was the kind of reception my grandpa and the other kids got on Cairnholm, I thought, no wonder they kept to themselves.

Martin cleared his throat. “So, Uncle, the bombing?”

“Oh, keep your hair on. Yes, yes, the goddamned Jerries. Who could forget them?” He launched into a long-winded description of what life on the island was like under threat of German air raids: the blaring sirens; the panicked scrambles for shelter; the volunteer air-raid warden who ran from house to house at night making sure shades had been drawn and streetlights were put out to rob enemy pilots of easy targets. They prepared as best they could but never really thought they’d get hit, given all the ports and factories on the mainland, all much more important targets than Cairnholm’s little gun emplacement. But one night, the bombs began to fall.

“The noise was dreadful,” Oggie said. “It was like giants stamping across the island, and it seemed to go on for ages. They gave us a hell of a pounding, though no one in town was killed, thank heaven. Can’t say the same for our gunner boys—though they gave as good as they got—nor the poor souls at the orphan home. One bomb was all it took. Gave up their lives for Britain, they did. So wherever they was from, God bless ’em for that.”

“Do you remember when it happened?” I asked. “Early in the war or late?”

“I can tell you the exact day,” he said. “It was the third of September, 1940.”

The air seemed to go out of the room. I flashed to my grandfather’s ashen face, his lips just barely moving, uttering those very words. September third, 1940.

“Are you—you sure about that? That it was that day?”

“I never got to fight,” he said. “Too young by a year. That one night was my whole war. So, yes, I’m sure.”

I felt numb, disconnected. It was too strange. Was someone playing a joke on me, I wondered—a weird, unfunny joke?

“And there weren’t any survivors at all?” Martin asked.

The old man thought for a moment, his gaze drifting up to the ceiling. “Now that you mention it,” he said, “I reckon there were. Just one. A young man, not much older than this boy here.” His rocking stopped as he remembered it. “Walked into town the morning after with not a scratch upon him. Hardly seemed perturbed at all, considering he’d just seen all his mates go to their reward. It was the queerest thing.”

“He was probably in shock,” Martin said.

“I shouldn’t wonder,” replied Oggie. “He spoke only once, to ask my father when the next boat was leaving for the mainland. Said he wanted to take up arms directly and kill the damned monsters who murdered his people.”

Oggie’s story was nearly as far-fetched as the ones Grandpa Portman used to tell, and yet I had no reason to doubt him.

“I knew him,” I said. “He was my grandfather.”

They looked at me, astonished. “Well,” Billy said. “I’ll be blessed.”

I excused myself and stood up. Martin, remarking that I seemed out of sorts, offered to walk me back to the pub, but I declined. I needed to be alone with my thoughts. “Come and see me soon, then,” he said, and I promised I would.

I took the long way back, past the swaying lights of the harbor, the air heavy with brine and with chimney smoke from a hundred hearth fires. I walked to the end of a dock and watched the moon rise over the water, imagining my grandfather standing there on that awful morning after, numb with shock, waiting for a boat that would take him away from all the death he’d endured, to war, and more death. There was no escaping the monsters, not even on this island, no bigger on a map than a grain of sand, protected by mountains of fog and sharp rocks and seething tides. Not anywhere. That was the awful truth my grandfather had tried to protect me from.

In the distance, I heard the generators sputter and spin down, and all the lights along the harbor and in house windows behind me surged for a moment before going dark. I imagined how such a thing might look from an airplane’s height—the whole island suddenly winking out, as if it had never been there at all. A supernova in miniature.