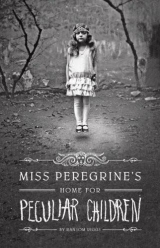

Текст книги "Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children"

Автор книги: Ransom Riggs

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

“It could take twenty minutes to get him back to shore,” I said. “He could just as easily die on the way.”

“I don’t know what else to do!”

“The lighthouse is close,” Bronwyn said. “We’ll take him there.”

“Then Golan will make us all bleed to death!” I said.

“No, he won’t,” replied Bronwyn.

“Why not? Are you bullet-proof?”

“Maybe,” Bronwyn replied mysteriously, then took a breath and disappeared down the ladder.

“What’s she talking about?” I said.

Emma looked worried. “I haven’t a clue. But whatever it is, she’d better hurry.” I looked down to see what Bronwyn was doing but instead caught a glimpse of Millard on the ladder below us, surrounded by curious flashlight fish. Then I felt the hull vibrate against my feet, and a moment later Bronwyn surfaced holding a rectangular piece of metal about six feet by four, with a riveted round hole in the top. She had wrenched the cargo hold’s door from its hinges.

“And what are you going to do with that?” Emma said.

“Go to the lighthouse,” she replied. Then she stood up and held the door in front of her.

“Wyn, he’ll shoot you!” Emma cried, and then a shot rang out—and caromed right off the door.

“That’s amazing!” I said. “It’s a shield!”

Emma laughed. “Wyn, you’re a genius!”

“Millard can ride my back,” she said. “The rest of you, fall in behind.”

Emma brought Millard out of the water and hung his arms around Bronwyn’s neck. “It’s magnificent down there,” he said. “Emma, why did you never tell me about the angels?”

“What angels?”

“The lovely green angels who live just below.” He was shivering, his voice dreamy. “They kindly offered to take me to heaven.”

“No one’s going to heaven just yet,” Emma said, looking worried. “You just hang on to Bronwyn, all right?”

“Very well,” he said vacantly.

Emma stood behind Millard, pressing him into Bronwyn’s back so he wouldn’t slide off. I stood behind Emma, taking up the rear of our strange little conga line, and we began to plod forward across the wreck toward the lighthouse.

We were a big target, and right away Golan began to empty his gun at us. The sound of his bullets bouncing off the door was deafening—but somehow reassuring—but after about a dozen shots he stopped. I wasn’t optimistic enough to think he’d run out of bullets, though.

Reaching the end of the wreck, Bronwyn guided us carefully into open water, always keeping the massive door held out in front of us. Our conga line became a chain of dog-paddlers swimming in a knot behind her. Emma talked to Millard as we paddled, making him answer questions so he wouldn’t drift into unconsciousness.

“Millard! Who’s the prime minister?”

“Winston Churchhill,” he said. “Have you gone daft?”

“What’s the capital of Burma?”

“Lord, I’ve no idea. Rangoon.”

“Good! When’s your birthday?”

“Will you quit shouting and let me bleed in peace!”

It didn’t take long to cross the short distance between the wreck and the lighthouse. As Bronwyn shouldered our shield and climbed onto the rocks, Golan fired a few more shots, and their impact threw her off balance. As we cowered behind her, she wobbled and nearly slipped backward off the rocks, which between her weight and the door’s would’ve crushed us all. Emma planted her hands on the small of Bronwyn’s back and pushed, and finally both Bronwyn and the door tottered forward onto dry land. We scrambled after her in a pack, shivering in the crisp night air.

Fifty yards across at its widest, the lighthouse rocks were technically a tiny island. At the lighthouse’s rusted base were a dozen stone steps leading to an open door, where Golan stood with his pistol aimed squarely in our direction.

I risked a peek through the porthole. He held a small cage in one hand, and inside were two flapping birds mashed so close together I could hardly tell one from the other.

A shot whizzed past and I ducked.

“Come any closer and I’ll shoot them both!” Golan shouted, rattling the cage.

“He’s lying,” I said. “He needs them.”

“You don’t know that,” said Emma. “He’s a madman, after all.”

“Well we can’t just do nothing.”

“Rush him!” Bronwyn said. “He won’t know what to do. But if it’s going to work we’ve got to go NOW!”

And before we had a chance to weigh in, Bronwyn was running toward the lighthouse. We had no choice but to follow—she was carrying our protection, after all—and a moment later bullets were clanging against the door and chipping at the rocks around our feet.

It was like hanging from the back of a speeding train. Bronwyn was terrifying: She bellowed like a barbarian, the veins in her neck bulging, with Millard’s blood smeared all over her arms and back. I was very glad, in that moment, not to be on the other side of the door.

As we neared the lighthouse, Bronwyn shouted, “Get behind the wall!” Emma and I grabbed Millard and cut left to take cover behind the far side of the lighthouse. As we ran, I saw Bronwyn lift the door above her head and hurl it toward Golan.

There was a thunderous crash quickly followed by a scream, and moments later Bronwyn joined us behind the wall, flushed and panting.

“I think I hit him!” she said excitedly.

“What about the birds?” Emma said. “Did you even think about them?”

“He dropped ’em. They’re fine.”

“Well, you might’ve asked us before you went berserk and risked all our lives!” Emma cried.

“Quiet,” I hissed. We heard the faint sound of creaking metal. “What is that?”

“He’s climbing the stairs,” Emma replied.

“You’d better get after him,” croaked Millard. We looked at him, surprised. He was slumped against the wall.

“Not before we take care of you,” I said. “Who knows how to make a tourniquet?”

Bronwyn reached down and tore the leg of her pants. “I do,” she said. “I’ll stop his bleeding; you get the wight. I knocked him pretty good, but not good enough. Don’t give him a chance to get his wind back.”

I turned to Emma. “You up for this?”

“If it means I get to melt that wight’s face off,” she said, little arcs of flame pulsing between her hands, “then absolutely.”

* * *

Emma and I clambered over the ship’s door, which lay bent on the steps where it had landed, and entered the lighthouse. The building consisted mainly of one narrow and profoundly vertical room—a giant stairwell, essentially—dominated by a skeletal staircase that corkscrewed from the floor to a stone landing, more than a hundred feet up. We could hear Golan’s footsteps as he bounded up the stairs, but it was too dark to tell how far he was from the top.

“Can you see him?” I said, peering up the stairwell’s dizzying height.

My answer was a gunshot ricocheting off a wall nearby, followed by another that slammed into the floor at my feet. I jumped back, heart hammering.

“Over here!” Emma cried. She grabbed my arm and pulled me farther inside, to the one place Golan’s gunshots couldn’t reach us—directly under the stairs.

We climbed a few steps, which were already swaying like a boat in bad weather. “These are frightful!” Emma exclaimed, her fingers white-knuckled as they gripped the rail. “Even if we make it to the top without falling, he’ll only shoot us!”

“If we can’t go up,” I said, “maybe we can bring him down.” I began to rock back and forth where I stood, yanking on the railing and stomping my feet, sending shockwaves up the stairs. Emma looked at me like I was nuts for a second, but then got the idea and began to stomp and sway along with me. Pretty soon the staircase was rocking like crazy.

“What if the whole thing comes down?” Emma shouted.

“Let’s hope it doesn’t!”

We shook harder. Screws and bolts began to rain down. The rail was lurching so violently, I could hardly keep hold of it. I heard Golan scream a spectacular array of curses, and then something clattered down the stairs, landing nearby.

The first thing I thought was, Oh God, what if that was the birdcage—and I dashed down the stairs past Emma and ran out on the floor to check.

“What are you doing?!” Emma shouted. “He’ll shoot you!”

“No, he won’t!” I said, holding up Golan’s handgun in triumph. It felt warm from all the firing he’d done and heavy in my hand, and I had no idea if it still had bullets or even how, in the near darkness, to check. I tried in vain to remember something useful from the few shooting lessons Grandpa had been allowed to give me, but finally I just ran back up the steps to Emma.

“He’s trapped at the top,” I said. “We’ve got to take it slow, try to reason with him, or who knows what he’ll do to the birds.”

“I’ll reason him right over the side,” Emma replied through her teeth.

We began to climb. The staircase swayed terribly and was so narrow that we could only proceed in single-file, crouching so our heads wouldn’t hit the steps above. I prayed that none of the fasteners we’d shaken loose had secured anything crucial.

We slowed as we neared the top. I didn’t dare look down; there were only my feet on the steps, my hand sliding along the shivering rail and my other hand holding the gun. Nothing else existed.

I steeled myself for a surprise attack, but none came. The stairs ended at an opening in the stone landing above our heads, through which I could feel the snapping chill of night air and hear the whistle of wind. I stuck the gun through, followed by my head. I was tense and ready to fight, but I didn’t see Golan. On one side of me spun the massive light, housed behind thick glass—this close it was blinding, forcing me to shut my eyes as it swung past—and on the other side was a spindly rail. Beyond that was a void: ten stories of empty air and then rocks and churning sea.

I stepped onto the narrow walkway and turned to give Emma a hand up. We stood with our backs pressed again the lamp’s warm housing and our fronts to the wind’s chill. “The Bird’s close,” Emma whispered. “I can feel her.”

She flicked her wrist and a ball of angry red flame sprang to life. Something about its color and intensity made it clear that this time she hadn’t summoned a light, but a weapon.

“We should split up,” I said. “You go around one side and I’ll take the other. That way he won’t be able to sneak past us.”

“I’m scared, Jacob.”

“Me, too. But he’s hurt, and we have his gun.”

She nodded and touched my arm, then turned away.

I circled the lamp slowly, clenching the maybe-loaded gun, and gradually the view around the other side began to peel back.

I found Golan sitting on his haunches with his head down and his back against the railing, the birdcage between his knees. He was bleeding badly from a cut on the bridge of his nose, rivulets of red streaking his face like tears.

Clipped to the bars of the cage was a small red light. Every few seconds it blinked.

I took another step forward, and he raised his head to look at me. His face was a stubble of caked blood, his one white eye shot through with red, spit flecking the corners of his mouth.

He rose unsteadily, the cage in one hand.

“Put it down.”

He bent over as if to comply but faked away from me and tried to run. I shouted and gave chase, but as soon as he disappeared around the lamp housing I saw the glow of Emma’s fire flare across the concrete. Golan came howling back toward me, his hair smoking and one arm covering his face.

“Stop!” I screamed at him, and he realized he was trapped. He raised the cage, shielding himself, and gave it a vicious shake. The birds screeched and nipped at his hand through the bars.

“Is this what you want?” Golan shouted. “Go ahead, burn me! The birds will burn, too! Shoot me and I’ll throw them over the side!”

“Not if I shoot you in the head!”

He laughed. “You couldn’t fire a gun if you wanted to. You forget, I’m intimately familiar with your poor, fragile psyche. It’d give you nightmares.”

I tried to imagine it: curling my finger around the trigger and squeezing; the recoil and the awful report. What was so hard about that? Why did my hand shake just thinking about it? How many wights had my grandfather killed? Dozens? Hundreds? If he were here instead of me, Golan would be dead already, laid out while he’d been squatting against the rail in a daze. It was an opportunity I’d already wasted; a split-second of gutless indecision that might’ve cost the ymbryes their lives.

The giant lamp spun past, blasting us with light, turning us into glowing white cutouts. Golan, who was facing it, grimaced and looked away. Another wasted opportunity, I thought.

“Just put it down and come with us,” I said. “Nobody else has to get hurt.”

“I don’t know,” Emma said. “If Millard doesn’t make it, I might reconsider that.”

“You want to kill me?” Golan said. “Fine, get it over with. But you’ll only be delaying the inevitable, not to mention making things worse for yourselves. We know how to find you now. More like me are coming, and I can guarantee the collateral damage they do will make what I did to your friend seem downright charitable.”

“Get it over with?” Emma said, her flame sending a little pulse of sparks skyward. “Who said it would be quick?”

“I told you, I’ll kill them,” he said, drawing the cage to his chest.

She took a step toward him. “I’m eighty-eight years old,” she said. “Do I look like I need a pair of babysitters?” Her expression was steely, unreadable. “I can’t tell you how long we’ve been dying to get out from under that woman’s wing. I swear, you’d be doing us a favor.”

Golan swiveled his head back and forth, nervously sizing us up. Is she serious? For a moment he seemed genuinely frightened, but then he said, “You’re full of shit.”

Emma rubbed her palms together and pulled them slowly apart, drawing out a noose of flame. “Let’s find out.”

I wasn’t sure how far Emma would take this, but I had to step in before the birds went up in flames or were sent tumbling over the rail.

“Tell us what you want with those ymbrynes, and maybe she’ll go easy on you,” I said.

“We only want to finish what we started,” Golan said. “That’s all we’ve ever wanted.”

“You mean the experiment,” Emma said. “You tried it once, and look what happened. You turned yourselves into monsters!”

“Yes,” he said, “but what an unchallenging life it would be if we always got things right on the first go.” He smiled. “This time we’ll be harnessing the talents of all the world’s best time manipulators, like these two ladies here. We won’t fail again. We’ve had a hundred years to figure out what went wrong. Turns out all we needed was a bigger reaction!”

“A bigger reaction?” I said. “Last time you blew up half of Siberia!”

“If you must fail,” he said grandly, “fail spectacularly!”

I remembered Horace’s prophetic dream of ash clouds and scorched earth, and I realized what he’d been seeing. If the wights and hollows failed again, this time they’d destroy a lot more than five hundred miles of empty forest. And if they succeeded, and turned themselves into the deathless demigods they’d always dreamed of becoming ... I shuddered to imagine it. Living under them would be a hell all its own.

The light came around and blinded Golan again—I tensed, ready to lunge—but the moment sped by too quickly.

“It doesn’t matter,” Emma said. “Kidnap all the ymbrynes you want. They’ll never help you.”

“Yes, they will. They’ll do it or we’ll kill them one by one. And if that doesn’t work, we’ll kill you one by one, and make them watch.”

“You’re insane,” I told him.

The birds began to panic and screech. Golan shouted over them.

“No! What’s really insane is how you peculiars hide from the world when you could rule it—succumb to death when you could dominate it—and let the common genetic trash of the human race drive you underground when you could so easily make them your slaves, as they rightly should be!” He drove home every sentence with another shake of the cage. “That’s insane!”

“Stop it!” Emma shouted.

“So you do care!” He shook the cage even harder. Suddenly, the little red light attached to its bars began to glow twice as bright, and Golan whipped his head around and searched the darkness behind him. Then he looked back at Emma and said, “You want them? Here!” and he pulled back and swung the cage at her face.

She cried out and ducked. Like a discus thrower, Golan continued the swing until the cage sailed over her head, then released. It flew out of his hands and over the rail, tumbling end over end into the night.

I cursed and Emma screamed and threw herself against the rail, clawing at the air as the cage fell toward the sea. In that moment of confusion, Golan leapt and knocked me to the ground. He slammed a fist into my stomach and another into my chin.

I was dizzy and couldn’t breathe. He grabbed for the gun, and it took every bit of my strength to keep him from snatching it. Because he wanted it so badly, I knew it must’ve been loaded. I would’ve thrown it over the rail, but he almost had it and I couldn’t let go. Emma was screaming bastard, you bastard, and then her hands, gloved in flame, came from behind and seized him around the neck.

I heard Golan’s flesh singe like a cold steak on a hot grill. He howled and rolled off me, his thin hair going up in flame, and then his hands were around Emma’s throat, as though he didn’t mind burning as long as he could choke the life out of her. I jumped to my feet, held the gun in both hands, and pointed it.

I had, just for a moment, a clear shot. I tried to empty my mind and focus on steadying my arm, creating an imaginary line that extended from my shoulder through the sight to my target—a man’s head. No, not a man, but a corruption of one. A thing. A force that had arranged the murder of my grandfather and exploded all that I’d humbly called a life, poorly lived though it may have been, and carried me here to this place and this moment, in much the way less corrupt and violent forces had done my living and deciding for me since I was old enough to decide anything. Relax your hands, breathe in, hold it. But now I had a chance to force back, a slim nothing of a chance that I could already feel slipping away.

Now squeeze.

The pistol bucked in my hands and its report sounded like the earth breaking open, so tremendous and sudden that I shut my eyes. When I opened them again, everything seemed strangely frozen. Though Golan stood behind Emma with her arms locked in a hold, wrestling her toward the railing, it was as if they’d been cast in bronze. Had the ymbrynes turned human again and worked their magic on us? But then everything came unstuck and Emma wrenched her arms away and Golan began to totter backward, and he stumbled and sat heavily on the rail.

Gaping at me in surprise, he opened his mouth to speak but found he could not. He clapped his hands over the penny-sized hole I’d made in his throat, blood lacing through his fingers and running down his arms, and then the strength went out of him and he fell back, and he was gone.

The moment Golan disappeared from view, he was forgotten. Emma pointed out to sea and shouted, “There, there!” Following her finger and squinting into the distance I could barely pick out the pulse of a red LED bobbing on the waves. Then we were scrambling to the hatch and sprinting down and down the endless seesawing staircase, hopeless that we could reach the cage before it sank but hysterical to try to anyway.

We tore outside to find Millard wearing a tourniquet and Bronwyn by his side. He shouted something I didn’t quite hear, but it was enough to assure me he was alive. I grabbed Emma’s shoulder and said, “The boat!” pointing to where the stolen canoe had been lashed to a rock, but it was too far away, on the wrong side of the lighthouse, and there was no time. Emma pulled me instead toward the open sea, and, running, we dashed ourselves into it.

I hardly felt the cold. All I could think about was reaching the cage before it disappeared beneath the waves. We tore at the water and sputtered and choked as black swells slapped our faces. It was difficult to tell how far away the beacon was, just a single point of light in a surging ocean of dark. It bobbed and fell and came and went, and twice we lost sight of it and had to stop, searching frantically before spotting it again.

The strong current was carrying the cage out to sea, and us with it. If we didn’t reach it soon, our muscles would fail and we’d drown. I kept this morbid thought to myself for as long as I could, but when the beacon disappeared a third time and we looked for it so long we couldn’t even be sure what section of the rolling black sea it had disappeared from, I shouted, “We have to go back!”

Emma wouldn’t listen. She swam ahead of me, farther out to sea. I grasped at her scissoring feet but she kicked me off.

“It’s gone! We aren’t going to find them!”

“Shut up, shut up!” she cried, and I could tell from her labored breaths that she was as exhausted as I was. “Just shut up and look!”

I grabbed her and shouted in her face and she kicked at me, and when I wouldn’t let go and she couldn’t force me to, she began to cry, just wordless howls of despair.

I tried to drag her back toward the lighthouse, but she was like a stone in the water, pulling me down. “You have to swim!” I shouted. “Swim or we’ll drown!”

And then I saw it—the faintest blink of red light. It was close, just below the surface. At first I didn’t say anything, afraid I’d imagined it, but then it blinked a second time.

Emma whooped and shouted. It looked like the cage had landed on another wreck—how else could it have come to rest so shallowly?—and because it had only just sunk, I told myself it was possible the birds were still alive.

We swam and prepared to dive for the cage, though I didn’t know where the breath would come from, we had so little left. Then, strangely, the cage seemed to rise toward us.

“What’s happening?” I shouted. “Is that a wreck?”

“Can’t be. There are none over here!”

“Then what the hell is that?”

It looked like a whale about to surface, long and massive and gray, or some ghost ship rising from its grave, and there erupted a sudden and powerful swell that came up from below and pushed us away. We tried to paddle against it but had no more luck than flotsam caught in a tidal wave, and then it thudded against our feet and we were rising, too, riding its back.

It came out of the water beneath us, hissing and clanking like some giant mechanical monster. We were caught in a sudden rush of foaming surf that raced off it in every direction, thrown hard onto a surface of metal grates. We hooked our fingers through the grates to keep from being washed into the sea. I squinted through the salt spray and saw that the cage had come to rest between what looked like two fins jutting from the monster’s back, one smaller and one larger. And then the lighthouse beam swept past, and in its gleam I realized they weren’t fins at all but a conning tower and a giant bolted-down gun. This thing we were riding wasn’t a monster or a wreck or a whale—

“It’s a U-boat!” I shouted. That it had risen right beneath our feet was no coincidence. It had to be what Golan was waiting for.

Emma was already on her feet and sprinting across the rolling deck toward the cage. I scrambled to stand. As I began to run a wave flashed over the deck and knocked us both down.

I heard a shout and looked up to see a man in a gray uniform rise from a hatch in the conning tower and level a gun at us.

Bullets rained down, hammering the deck. The cage was too far away—we’d be torn to pieces before we could reach it—but I could see that Emma was about to try anyway.

I ran and tackled her and we tumbled sideways off the deck and into the water. The black sea closed above us. Bullets peppered the water, leaving trails of bubbles in their wake.

When we surfaced again, she grabbed me and screamed, “Why did you do that? I nearly had them!”

“He was about to kill you!” I said, wrestling away—and then it occurred to me that she hadn’t even seen him, she’d been so focused on the cage, so I pointed up at the deck, where the gunner was striding toward it. He picked the cage up and rattled it. Its door hung open, and I thought I saw movement inside—some reason for hope—and then the lighthouse beam washed over everything. I saw the gunner’s face full in the light, his mouth curled into a leering grin, his eyes depthless and blank. He was a wight.

He reached into the cage and pulled out a single sodden bird. From the conning tower, another soldier whistled to him, and he ran back toward the hatch with it.

The sub began to rattle and hiss. The water around us churned as if boiling.

“Swim or it’ll suck us down with it!” I shouted to Emma. But she hadn’t heard me—her eyes were locked elsewhere, on a patch of dark water near the stern of the boat.

She swam for it. I tried to stop her but she fought me off. Then, over the whine of the sub, I heard it—a high, shrieking call. Miss Peregrine!

We found her bobbing in the waves, struggling to keep her head above water, one wing flapping, the other broken looking. Emma scooped her up. I screamed that we had to go.

We swam away with what little strength we had. Behind us, a whirlpool was opening up, all the water displaced by the sub rushing back to fill the void as it sank. The sea was consuming itself and trying to consume us, too, but we had with us now a screeching winged symbol of victory, or half a victory at least, and she gave us the strength to fight the unnatural current. Then we heard Bronwyn shouting our names, and our brawny friend came crashing through the waves to tow us back to safety.

* * *

We lay on the rocks beneath the clearing sky, gasping for air and trembling with exhaustion. Millard and Bronwyn had so many questions, but we had no breath to answer them. They had seen Golan’s body fall and the submarine rise and sink and Miss Peregrine come out of the water but not Miss Avocet; they understood what they needed to. They hugged us until we stopped shaking, and Bronwyn tucked the headmistress under her shirt for warmth. Once we’d recovered a little, we retrieved Emma’s canoe and pushed off toward the shore.

When we got there, the children all waded into the shallows to meet us.

“We heard shooting!”

“What was that strange boat?”

“Where’s Miss Peregrine?”

We climbed out of the rowboat, and Bronwyn raised her shirt to reveal the bird nuzzled there. The children crowded around, and Miss Peregrine lifted her beak and crowed at them to show that she was tired but all right. A cheer went up.

“You did it!” Hugh shouted.

Olive danced a little jig and sang, “The Bird, the Bird, the Bird! Emma and Jacob saved the Bird!”

But the celebration was brief. Miss Avocet’s absence was quickly noted, as was Millard’s alarming condition. His tourniquet was tight, but he’d lost a lot of blood and was weakening. Enoch gave him his coat, Fiona offered her woolen hat.

“We’ll take you to see the doctor in town,” Emma said to him.

“Nonsense,” Millard replied. “The man’s never laid eyes on an invisible boy, and he wouldn’t know what to do with one if he did. He’d either treat the wrong limb or run away screaming.”

“It doesn’t matter if he runs away screaming,” Emma said. “Once the loop resets he won’t remember a thing.”

“Look around you. The loop should’ve reset an hour ago.”

Millard was right—the skies were quiet, the battle had ended, but rolling drifts of bomb smoke still mixed with the clouds.

“That’s not good,” Enoch said, and everyone got quiet.

“In any case,” Millard continued, “all the supplies I need are in the house. Just give me a bolt of Laudanum and swab the wound with alcohol. It’s only the fleshy part anyway. In three days I’ll be right as rain.”

“But it’s still bleeding,” Bronwyn said, pointing out red droplets that dotted the sand beneath him.

“Then tie the damn tourniquet tighter!”

She did, and Millard gasped in a way that made everyone cringe, then fainted into her arms.

“Is he all right?” Claire asked.

“Just blacked out is all,” said Enoch. “He ain’t as fit as he pretends to be.”

“What do we do now?”

“Ask Miss Peregrine!” Olive said.

“Right. Put her down so she can change back,” said Enoch. “She can’t very well tell us what to do while she’s still a bird.”

So Bronwyn set her on a dry patch of sand, and we all stood back and waited. Miss Peregrine hopped a few times and flapped her good wing and then swiveled her feathered head around and blinked at us—but that was it. She remained a bird.

“Maybe she wants a little privacy,” Emma suggested. “Let’s turn our backs.”

So we did, forming a ring around her. “It’s safe now, Miss P,” said Olive. “No one’s looking!”

After a minute, Hugh snuck a peek and said, “Nope, still a bird.”

“Maybe she’s too tired and cold,” Claire said, and enough of the others agreed this was plausible that it was decided we would go back to the house, treat Millard with what supplies we had, and hope that with some time to rest, both the headmistress and her loop would return to normal.