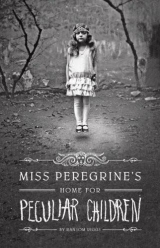

Текст книги "Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children"

Автор книги: Ransom Riggs

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

The next present was the digital camera I’d begged my parents for all last summer. “Wow,” I said, testing its weight in my hand. “This is awesome.”

“I’m outlining a new bird book,” my dad said. “I was thinking maybe you could take the pictures.”

“A new book!” my mom exclaimed. “That’s a phenomenal idea, Frank. Speaking of which, whatever happened to that last book you were working on?” Clearly, she’d had a few glasses of wine.

“I’m still ironing out a few things,” my dad replied quietly.

“Oh, I see.” I could hear Uncle Bobby snickering.

“Okay!” I said loudly, reaching for the last present. “This one’s from Aunt Susie.”

“Actually,” my aunt said as I began tearing away the wrapping paper, “it’s from your grandfather.”

I stopped midtear. The room went dead quiet, people looking at Aunt Susie as if she’d invoked the name of some evil spirit. My dad’s jaw tensed and my mom shot back the last of her wine.

“Just open it and you’ll see,” Aunt Susie said.

I ripped away the rest of the wrapping paper to find an old hardback book, dog-eared and missing its dust jacket. It was The Selected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. I stared at it as if trying to read through the cover, unable to comprehend how it had come to occupy my now-trembling hands. No one but Dr. Golan knew about the last words, and he’d promised on several occasions that unless I threatened to guzzle Drano or do a backflip off the Sunshine Skyway bridge, everything we talked about in his office would be held in confidence.

I looked at my aunt, a question on my face that I didn’t quite know how to ask. She managed a weak smile and said, “I found it in your grandfather’s desk when we were cleaning out the house. He wrote your name in the front. I think he meant for you to have it.”

God bless Aunt Susie. She had a heart after all.

“Neat. I didn’t know your grandpa was a reader,” my mom said, trying to lighten the mood. “That was thoughtful.”

“Yes,” said my dad through clenched teeth. “Thank you, Susan.”

I opened the book. Sure enough, the title page bore an inscription in my grandfather’s shaky handwriting.

I got up to leave, afraid I might start crying in front of everyone, and something slipped out from between the pages and fell to the floor.

I bent to pick it up. It was a letter.

Emerson. The letter.

I felt the blood drain from my face. My mother leaned toward me and in a tense whisper asked if I needed a drink of water, which was Mom-speak for keep it together, people are staring. I said, “I feel a little, uh ...” and then, with one hand over my stomach, I bolted to my room.

* * *

The letter was handwritten on fine, unlined paper in looping script so ornate it was almost calligraphy, the black ink varying in tone like that of an old fountain pen. It read:

As promised, the writer had enclosed an old snapshot.

I held it under the glow of my desk lamp, trying to read some detail in the woman’s silhouetted face, but there was none to find. The image was so strange, and yet it was nothing like my grandfather’s pictures. There were no tricks here. It was just a woman—a woman smoking a pipe. It looked like Sherlock Holmes’s pipe, curved and drooping from her lips. My eyes kept coming back to it.

Was this what my grandfather had meant for me to find? Yes, I thought, it has to be—not the letters of Emerson, but a letter, tucked inside Emerson’s book. But who was this headmistress, this Peregrine woman? I studied the envelope for a return address but found only a fading postmark that read Cairnholm Is., Cymru, UK.

UK—that was Britain. I knew from studying atlases as a kid that Cymru meant Wales. Cairnholm Is had to be the island Miss Peregrine had mentioned in her letter. Could it have been the same island where my grandfather lived as a boy?

Nine months ago he’d told me to “find the bird.” Nine years ago he had sworn that the children’s home where he’d lived was protected by one—by “a bird who smoked a pipe.” At age seven I’d taken this statement literally, but the headmistress in the picture was smoking a pipe, and her name was Peregrine, a kind of hawk. What if the bird my grandfather wanted me to find was actually the woman who’d rescued him—the headmistress of the children’s home? Maybe she was still on the island, after all these years, old as dirt but sustained by a few of her wards, children who’d grown up but never left.

For the first time, my grandfather’s last words began to make a strange kind of sense. He wanted me to go to the island and find this woman, his old headmistress. If anyone knew the secrets of his childhood, it would be her. But the envelope’s postmark was fifteen years old. Was it possible she was still alive? I did some quick calculations in my head: If she’d been running a children’s home in 1939 and was, say, twenty-five at the time, then she’d be in her late nineties today. So it was possible—there were people older than that in Englewood who still lived by themselves and drove—and even if Miss Peregrine had passed away in the time since she’d sent the letter, there might still be people on Cairnholm who could help me, people who had known Grandpa Portman as a kid. People who knew his secrets.

We, she had written. Those few who remain.

* * *

As you can imagine, convincing my parents to let me spend part of my summer on a tiny island off the coast of Wales was no easy task. They—particularly my mother—had many compelling reasons why this was a wretched idea, including the cost, the fact that I was supposed to spend the summer with Uncle Bobby learning how to run a drug empire, and that I had no one to accompany me, since neither of my parents had any interest in going and I certainly couldn’t go alone. I had no effective rebuttals, and my reason for wanting to make the trip—I think I’m supposed to—wasn’t something I could explain without sounding even crazier than they already feared I was. I certainly wasn’t going to tell my parents about Grandpa Portman’s last words or the letter or the photo—they would’ve had me committed. The only sane-sounding arguments I could come up with were things like, “I want to learn more about our family history” and the never-persuasive “Chad Kramer and Josh Bell are going to Europe this summer. Why can’t I?” I brought these up as frequently as possible without seeming desperate (even once resorting to “it’s not like you don’t have the money,” a tactic I instantly regretted), but it looked like it wasn’t going to happen.

Then several things happened that helped my case enormously. First, Uncle Bobby got cold feet about my spending the summer with him—because who wants a nutcase living in their house? So my schedule was suddenly wide open. Next, my dad learned that Cairnholm Island is a super-important bird habitat, and, like, half the world’s population of some bird that gives him a total ornithology boner lives there. He started talking a lot about his hypothetical new bird book, and whenever the subject came up I did my best to encourage him and sound interested. But the most important factor was Dr. Golan. After a surprisingly minimal amount of coaxing by me, he shocked us all by not only signing off on the idea but also encouraging my parents to let me go.

“It could be important for him,” he told my mother after a session one afternoon. “It’s a place that’s been so mythologized by his grandfather that visiting could only serve to demystify it. He’ll see that it’s just as normal and unmagical as anyplace else, and, by extension, his grandfather’s fantasies will lose their power. It could be a highly effective way of combating fantasy with reality.”

“But I thought he already didn’t believe that stuff,” my mother said, turning to me. “Do you, Jake?”

“I don’t,” I assured her.

“Not consciously he doesn’t,” Dr. Golan said. “But it’s his unconscious that’s causing him problems right now. The dreams, the anxiety.”

“And you really think going there could help?” my mother said, narrowing her eyes at him as if readying herself to hear the unvarnished truth. When it came to things I should or should not be doing, Dr. Golan’s word was law.

“I do,” he replied.

And that was all it took.

* * *

After that, things fell into place with astonishing speed. Plane tickets were bought, schedules scheduled, plans laid. My dad and I would go for three weeks in June. I wondered if that was too long, but he claimed he needed at least that much time to make a thorough study of the island’s bird colonies. I thought mom would object—three whole weeks!—but the closer our trip got, the more excited for us she seemed. “My two men,” she would say, beaming, “off on a big adventure!”

I found her enthusiasm kind of touching, actually—until the afternoon I overheard her talking on the phone to a friend, venting about how relieved she’d be to “have her life back” for three weeks and not have “two needy children to worry about.”

I love you too, I wanted to say with as much hurtful sarcasm as I could muster, but she hadn’t seen me, and I kept quiet. I did love her, of course, but mostly just because loving your mom is mandatory, not because she was someone I think I’d like very much if I met her walking down the street. Which she wouldn’t be, anyway; walking is for poor people.

During the three-week window between the end of school and the start of our trip, I did my best to verify that Ms. Alma LeFay Peregrine still resided among the living, but Internet searches turned up nothing. Assuming she was still alive, I had hoped to get her on the phone and at least warn her that I was coming, but I soon discovered that almost no one on Cairnholm even had a phone. I found only one number for the entire island, so that’s the one I dialed.

It took nearly a minute to connect, the line hissing and clicking, going quiet, then hissing again, so that I could feel every mile of the vast distance my call was spanning. Finally I heard that strange European ring—waaap-waaap ... waaap-waaap—and a man whom I could only assume was profoundly intoxicated answered the phone.

“Piss hole!” he bellowed. There was an unholy amount of noise in the background, the kind of dull roar you’d expect at the height of a raging frat party. I tried to identify myself, but I don’t think he could hear me.

“Piss hole!” he bellowed again. “Who’s this now?” But before I could say anything he’d pulled the receiver away from his head to shout at someone. “I said shaddap, ya dozy bastards, I’m on the—”

And then the line went dead. I sat with the receiver to my ear for a long, puzzled moment, then hung up. I didn’t bother calling back. If Cairnholm’s only phone connected to some den of iniquity called the “piss hole,” how did that bode for the rest of the island? Would my first trip to Europe be spent evading drunken maniacs and watching birds evacuate their bowels on rocky beaches? Maybe so. But if it meant that I’d finally be able to put my grandfather’s mystery to rest and get on with my unextraordinary life, anything I had to endure would be worth it.

Chapter Three

Fog closed around us like a blindfold. When the captain announced that we were nearly there, at first I thought he was kidding; all I could see from the ferry’s rolling deck was an endless curtain of gray. I clutched the rail and stared into the green waves, contemplating the fish who might soon be enjoying my breakfast, while my father stood shivering beside me in shirtsleeves. It was colder and wetter than I’d ever known June could be. I hoped, for his sake and mine, that the grueling thirty-six hours we’d braved to get this far—three airplanes, two layovers, shift-napping in grubby train stations, and now this interminable gut-churning ferry ride—would pay off. Then my father shouted, “Look!” and I raised my head to see a towering mountain of rock emerge from the blank canvas before us.

It was my grandfather’s island. Looming and bleak, folded in mist, guarded by a million screeching birds, it looked like some ancient fortress constructed by giants. As I gazed up at its sheer cliffs, tops disappearing in a reef of ghostly clouds, the idea that this was a magical place didn’t seem so ridiculous.

My nausea seemed to vanish. Dad ran around like a kid on Christmas, his eyes glued to the birds wheeling above us. “Jacob, look at that!” he cried, pointing to a cluster of airborne specks. “Manx Shearwaters!”

As we drew nearer the cliffs, I began to notice odd shapes lurking underwater. A passing crewman caught me leaning over the rail to stare at them and said, “Never seen a shipwreck before, eh?”

I turned to him. “Really?”

“This whole area’s a nautical graveyard. It’s like the old captains used to say—’Twixt Hartland Point and Cairnholm Bay is a sailor’s grave by night or day!’ ”

Just then we passed a wreck that was so near the surface, the outline of its greening carcass so clear, that it looked like it was about to rise out of the water like a zombie from a shallow grave. “See that one?” he said, pointing at it. “Sunk by a U-boat, she was.”

“There were U-boats around here?”

“Loads. Whole Irish Sea was rotten with German subs. Wager you’d have half a navy on your hands if you could unsink all the ships they torpedoed.” He arched one eyebrow dramatically, then walked off laughing.

I jogged along the deck to the stern, tracking the shipwreck as it disappeared beneath our wake. Then, just as I was starting to wonder if we’d need climbing gear to get onto the island, its steep cliffs sloped down to meet us. We rounded a headland to enter a rocky half-moon bay. In the distance I saw a little harbor bobbing with colorful fishing boats, and beyond it a town set into a green bowl of land. A patchwork of sheep-speckled fields spread across hills that rose away to meet a high ridge, where a wall of clouds stood like a cotton parapet. It was dramatic and beautiful, unlike any place I’d seen. I felt a little thrill of adventure as we chugged into the bay, as if I were sighting land where maps had noted only a sweep of undistinguished blue.

The ferry docked and we humped our bags into the little town. Upon closer inspection I decided it was, like a lot of things, not as pretty up close as it seemed from a distance. Whitewashed cottages, quaint except for the satellite dishes sprouting from their roofs, lined a small grid of muddy gravel streets. Because Cairnholm was too distant and too inconsequential to justify the cost of running power lines from the mainland, foul-smelling diesel generators buzzed on every corner like angry wasps, harmonizing with the growl of tractors, the island’s only vehicular traffic. At the edges of town, ancient-looking cottages stood abandoned and roofless, evidence of a shrinking population, children lured away from centuries-old fishing and farming traditions by more glamorous opportunities elsewhere.

We dragged our stuff through town looking for something called the Priest Home, where my dad had booked a room. I pictured an old church converted into a bed and breakfast—nothing fancy, just somewhere to sleep when we weren’t watching birds or chasing down leads. We asked a few locals for directions but got only confused looks in return. “They speak English, right?” my dad wondered aloud. Just as my hand was beginning to ache from the unreasonable weight of my suitcase, we came upon a church. We thought we’d found our accommodations, until we went inside and saw that it had indeed been converted, but into a dingy little museum, not a B&B.

We found the part-time curator in a room hung with old fishing nets and sheep shears. His face lit up when he saw us, then fell when he realized we were only lost.

“I reckon you’re after the Priest Hole,” he said. “It’s got the only rooms to let on the island.”

He proceeded to give us directions in a lilting accent, which I found enormously entertaining. I loved hearing Welsh people talk, even if half of what they said was incomprehensible to me. My dad thanked the man and turned to go, but he’d been so helpful, I hung back to ask him another question.

“Where can we find the old children’s home?”

“The old what?” he said, squinting at me.

For an awful moment I was afraid we’d come to the wrong island or, worse yet, that the home was just another thing my grandfather had invented.

“It was a home for refugee kids?” I said. “During the war? A big house?”

The man chewed his lip and regarded me doubtfully, as if deciding whether to help or to wash his hands of the whole thing. But he took pity on me. “I don’t know about any refugees,” he said, “but I think I know the place you mean. It’s way up the other side of the island, past the bog and through the woods. Though I wouldn’t go mucking about up there alone, if I was you. Stray too far from the path and that’s the last anyone’ll hear of you—nothing but wet grass and sheep patties to keep you from going straight over a cliff.”

“That’s good to know,” my dad said, eyeing me. “Promise me you won’t go by yourself.”

“All right, all right.”

“What’s your interest in it, anyhow?” the man said. “It’s not exactly on the tourist maps.”

“Just a little genealogy project,” my father replied, lingering near the door. “My dad spent a few years there as a kid.” I could tell he was eager to avoid any mention of psychiatrists or dead grandfathers. He thanked the man again and quickly ushered me out the door.

Following the curator’s directions, we retraced our steps until we came to a grim-looking statue carved from black stone, a memorial called the Waiting Woman dedicated to islanders lost at sea. She wore a pitiful expression and stood with arms outstretched in the direction of the harbor, many blocks away, but also toward the Priest Hole, which was directly across the street. Now, I’m no hotel connoisseur, but one glance at the weathered sign told me that our stay was unlikely to be a four-star mints-on-your-pillow-type experience. Printed in giant script at the top was WINES, ALES, SPIRITS. Below that, in more modest lettering, Fine Food. Handwritten along the bottom, clearly an afterthought, was Rooms to Let, though the s had been struck out, leaving just the singular Room. As we lugged our bags toward the door, my father grumbling about con men and false advertising, I glanced back at the Waiting Woman and wondered if she wasn’t just waiting for someone to bring her a drink.

We squeezed our bags through the doorway and stood blinking in the sudden gloom of a low-ceilinged pub. When my eyes had adjusted, I realized that hole was a pretty accurate description of the place: tiny leaded windows admitted just enough light to find the beer tap without tripping over tables and chairs on the way. The tables, worn and wobbling, looked like they might be more useful as firewood. The bar was half-filled, at whatever hour of the morning it was, with men in various states of hushed intoxication, heads bowed prayerfully over tumblers of amber liquid.

“You must be after the room,” said the man behind the bar, coming out to shake our hands. “I’m Kev and these are the fellas. Say hullo, fellas.”

“Hullo,” they muttered, nodding at their drinks.

We followed Kev up a narrow staircase to a suite of rooms (plural!) that could charitably be described as basic. There were two bedrooms, the larger of which Dad claimed, and a room that tripled as a kitchen, dining room, and living room, meaning that it contained one table, one moth-eaten sofa, and one hotplate. The bathroom worked “most of the time,” according to Kev, “but if it ever gets dicey, there’s always Old Reliable.” He directed our attention to a portable toilet in the alley out back, conveniently visible from my bedroom window.

“Oh, and you’ll need these,” he said, fetching a pair of oil lamps from a cabinet. “The generators stop running at ten since petrol’s so bloody expensive to ship out, so either you get to bed early or you learn to love candles and kerosene.” He grinned. “Hope it ain’t too medieval for ya!”

We assured Kev that outhouses and kerosene would be just fine, sounded like fun, in fact—a little adventure, yessir—and then he led us downstairs for the finalleg of our tour. “You’re welcome to take your meals here,” he said, “and I expect you will, on account of there’s nowhere else to eat. If you need to make a call, we got a phone box in the corner there. Sometimes there’s a bit of a queue for it, though, since we get doodly for mobile reception out here and you’re looking at the only land-line on the island. That’s right, we got it all—only food, only bed, only phone!” And he leaned back and laughed, long and loud.

The only phone on the island. I looked over at it—it was the kind that had a door you could pull shut for privacy, like the ones you see in old movies—and realized with dawning horror that this was the Grecian orgy, this was the raging frat party I had been connected to when I called the island a few weeks ago. This was the piss hole.

Kev handed my dad the keys to our rooms. “Any questions,” he said, “you know where to find me.”

“I have a question,” I said. “What’s a piss—I mean, a priest hole?”

The men at the bar burst into laughter. “Why, it’s a hole for priests, of course!” one said, which made the rest of them laugh even harder.

Kev walked over to an uneven patch of floorboards next to the fireplace, where a mangy dog lay sleeping. “Right here,” he said, tapping what appeared to be a door in the floor with his shoe. “Ages ago, when just being a Catholic could get you hung from a tree, clergyfolk came here seeking refuge. If Queen Elizabeth’s crew of thugs come chasing after, we hid whoever needed hiding in snug little spots like this—priest holes.” It struck me the way he said we, as if he’d known those long-dead islanders personally.

“Snug indeed!” one of the drinkers said. “Bet they were warm as toast and tight as drums down there!”

“I’d take warm and snug to strung up by priest killers any day,” said another.

“Here, here!” the first man said. “To Cairnholm—may she always be our rock of refuge!”

“To Cairnholm!” they chorused, and raised their glasses together.

* * *

Jet-lagged and exhausted, we went to sleep early—or rather we went to our beds and lay in them with pillows covering our heads to block out the thumping cacophony that issued through the floorboards, which grew so loud that at one point I thought surely the revelers had invaded my room. Then the clock must’ve struck ten because all at once the buzzing generators outside sputtered and died, as did the music from downstairs and the streetlight that had been shining through my window. Suddenly I was cocooned in silent, blissful darkness, with only the whisper of distant waves to remind me where I was.

For the first time in months, I fell into a deep, nightmare-free slumber. I dreamed instead about my grandfather as a boy, about his first night here, a stranger in a strange land, under a strange roof, owing his life to people who spoke a strange tongue. When I awoke, sun streaming through my window, I realized it wasn’t just my grandfather’s life that Miss Peregrine had saved, but mine, too, and my father’s. Today, with any luck, I would finally get to thank her.

I went downstairs to find my dad already bellied up to a table, slurping coffee and polishing his fancy binoculars. Just as I sat down, Kev appeared bearing two plates loaded with mystery meat and fried toast. “I didn’t know you could fry toast,” I remarked, to which Kev replied that there wasn’t a food he was aware of that couldn’t be improved by frying.

Over breakfast, Dad and I discussed our plan for the day. It was to be a kind of scout, to familiarize ourselves with the island. We’d scope out my dad’s bird-watching spots first and then find the children’s home. I scarfed my food, anxious to get started.

Well fortified with grease, we left the pub and walked through town, dodging tractors and shouting to each other over the din of generators until the streets gave way to fields and the noise faded behind us. It was a crisp and blustery day—the sun hiding behind giant cloudbanks only to burst out moments later and dapple the hills with spectacular rays of light—and I felt energized and hopeful. We were heading for a rocky beach where my dad had spotted a bunch of birds from the ferry. I wasn’t sure how we would reach it, though—the island was slightly bowl shaped, with hills that climbed toward its edges only to drop off at precarious seaside cliffs—but at this particular spot the edge had been rounded off and a path led down to a minor spit of sand along the water.

We picked our way down to the beach, where what seemed to be an entire civilization of birds were flapping and screeching and fishing in tide pools. I watched my father’s eyes widen. “Fascinating,” he muttered, scraping at some petrified guano with the stubby end of his pen. “I’m going to need some time here. Is that all right?”

I’d seen this look on his face before, and I knew exactly what “some time” meant: hours and hours. “Then I’ll go find the house by myself,” I said.

“Not alone, you aren’t. You promised.”

“Then I’ll find a person who can take me.”

“Who?”

“Kev will know someone.”

My dad looked out to sea, where a big rusted lighthouse jutted up from a pile of rocks. “You know what the answer would be if your mom were here,” he said.

My parents had differing theories about how much parenting I required. Mom was the enforcer, always hovering, but Dad hung back a little. He thought it was important that I make my own mistakes now and then. Also, letting me go would free him to play with guano all day.

“Okay,” he said, “but make sure you leave me the number of whoever you go with.”

“Dad, nobody here has phones.”

He sighed. “Right. Well, as long as they’re reliable.”

* * *

Kev was out running an errand, and because asking one of his drunken regulars to chaperone me seemed like a bad idea, I went into the nearest shop to ask someone who was at least gainfully employed. The door read FISHMONGER. I pushed it open to find myself cowering before a bearded giant in a blood-soaked apron. He left off decapitating fish to glare at me, dripping cleaver in hand, and I vowed never again to discriminate against the intoxicated.

“What the hell for?” he growled when I told him where I wanted to go. “Nothing over there but bogland and barmy weather.”

I explained about my grandfather and the children’s home. He frowned at me, then leaned over the counter to cast a doubtful glance at my shoes.

“I s’pose Dylan ain’t too busy to take you,” he said, pointing his cleaver at a kid about my age who was arranging fish in a freezer case, “but you’ll be wantin’ proper footwear. Wouldn’t do to let you go in them trainers—mud’ll suck ’em right off!”

“Really?” I said. “Are you sure?”

“Dylan! Fetch our man here a pair of Wellingtons!”

The kid groaned and made a big show of slowly closing the freezer case and cleaning his hands before slouching over to a wall of shelves packed with dry goods.

“Just so happens we’ve got some good sturdy boots on offer,” the fishmonger said. “Buy one get none free!” He burst out laughing and slammed his cleaver on a salmon, its head shooting across the blood-slicked counter to land perfectly in a little guillotine bucket.

I fished the emergency money Dad had given me from my pocket, figuring that a little extortion was a small price to pay to find the woman I’d crossed the Atlantic to meet.

I left the shop wearing a pair of rubber boots so large my sneakers fit inside and so heavy it was difficult to keep up with my begrudging guide.

“So, do you go to school on the island?” I asked Dylan, scurrying to catch up. I was genuinely curious—what was living here like for someone my age?

He muttered the name of a town on the mainland.

“What is that, an hour each way by ferry?”

“Yup.”

And that was it. He responded to further attempts at conversation with even fewer syllables—which is to say, none—so finally I just gave up and followed him. On the way out of town we ran into one of his friends, an older boy wearing a blinding yellow track suit and fake gold chains. He couldn’t have looked more out of place on Cairnholm if he’d been dressed like an astronaut. He gave Dylan a fist-bump and introduced himself as Worm.

“Worm?”

“It’s his stage name,” Dylan explained.

“We’re the sickest rapping duo in Wales,” Worm said. “I’m MC Worm, and this is the Sturgeon Surgeon, aka Emcee Dirty Dylan, aka Emcee Dirty Bizniss, Cairnholm’s number one beat-boxer. Wanna show this Yank how we do, Dirty D?”

Dylan looked annoyed. “Now?”

“Drop some next-level beats, son!”

Dylan rolled his eyes but did as he was asked. At first I thought he was choking on his tongue, except there was a rhythm to his sputtering coughs,—puhh, puh-CHAH, puh-puhhh, puh-CHAH—over which Worm began to rap.

“I likes to get wrecked up down at the Priest Hole / Your dad’s always there ’cause he’s on the dole / My rhymes is tight, yeah I make it look easy / Dylan’s beats are hot like chicken jalfrezi!”

Dylan stopped. “That don’t even make sense,” he said. “And it’s your dad who’s on the dole.”

“Oh shit, Dirty D let the beat drop!” Worm started beat-boxing while doing a passable robot, his sneakers twisting holes in the gravel. “Take the mic, D!”

Dylan seemed embarrassed but let the rhymes fly anyway. “I met a tight bird and her name was Sharon / She was keen on my tracksuit and the trainers I was wearin’ / I showed her the time, like Doctor Who / I thunk up this rhyme while I was in the loo!”

Worm shook his head. “The loo?”

“I wasn’t ready!”

They turned to me and asked what I thought. Considering that they didn’t even like each other’s rapping, I wasn’t sure what to say.

“I guess I’m more into music with, like, singing and guitars and stuff.”

Worm dismissed me with a wave of his hand. “He wouldn’t know a dope rhyme if it bit him in the bollocks,” he muttered.

Dylan laughed and they exchanged a series of complex, multistage handshake-fist-bump-high-fives.

“Can we go now?” I said.

They grumbled and dawdled a while longer, but pretty soon we were on our way, this time with Worm tagging along.