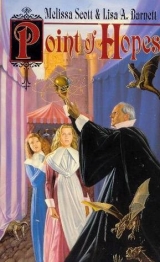

Текст книги "Point of Hopes"

Автор книги: Melissa Scott

Соавторы: Lisa Barnett

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

Adriana was waiting by the bar, a glass, not the usual tankard, in her hand. As he approached, she slid it toward him, and he took it with a nod of thanks. There was a dram or so of a clear, sweet‑smelling liquor in the bottom of it, and he drained it with a smile. The fiery liquor, distilled grain spirit with a strong flavor of mint, burned its way down his throat, and he set the glass down with a sigh.

“The next,” Adriana said, “you pay for.”

“That’s all right, then,” Eslingen answered. Menthe was imported from Altheim, and wasn’t cheap there. He shook his head. “I hope it’s done some good.”

“Can’t hurt,” Adriana answered. “Tell me something, Philip, what do your stars say about your death?”

Eslingen’s eyebrows rose. “That’s a personal question, surely–or were you planning something I should know of?”

“Neither killing nor bedding you, so get your mind off it,” Adriana said, but he could see the color rise in her dark cheeks. “No, I’m sorry, I know it came out wrong, but Felis–” She stopped, took a breath, looked suddenly younger than her years. “Anfelis told Mother why she won’t let Felis go, aside from he’s her only kid. His stars are bad for war, he’s likely to die by iron.”

Eslingen sighed, the menthe still hot on his tongue. “Then he’d be a fool to sign on, surely. You’d be surprised how many of us have those stars, though.” It was an ill‑omened thought. He smiled, and said brightly, “I, however, am like to live to a ripe age, comforting women and men to my last days.”

“Comfort seems unlikely,” Adriana retorted, and swung back behind the bar. Eslingen watched the kitchen door close behind her, his smile fading. Returning the Lucenan boy to his mother could only improve the Old Brown Dog’s reputation–he hoped. There were a handful of butchers, the journeyman Paas chief among them, who seemed to go out of their way to find something bad to say about anything Devynck did. Eslingen sighed again, suddenly aware that it was nearing midnight, and turned to survey the thinning crowd in the taproom. Everything seemed quiet enough, the three soldiers leaning close over an improvised dice board, Jasanten limping in from the garden, his crutch loud on the wooden floor, the woman musician who worked in one of the theaters in Point of Dreams nodding over her pint and a plate of bread and cheese, and Eslingen hoped that things would stay that way, at least until tonight’s closing.

Eslingen woke to the sound of someone knocking on his door. He rolled over, untangling himself from the sheets, and winced at the sunlight that seeped in through the cracks in the shutters. He could tell from the quality of the light that it was well before the second sunrise, and as if to confirm the bad news, the tower clock sounded. He counted the strokes–eight–before he sat up, swearing under his breath.

“Eslingen? You awake?”

Eslingen bit back a profane response, said, as moderately as he was able, “I am now.”

“There’s a pointsman to see you.”

“Seidos’s Horse!” Eslingen swallowed the rest of the curse. “What in the name of all the gods does he want with me?”

“Didn’t say.” The voice was definitely Loret’s. “Aagte says, will you please come down?”

Eslingen sighed. He doubted that Devynck had been that polite– unless of course she was trying to impress the pointsman–and he swung himself out of bed. “Tell her I’ll be down as soon as I put some clothes on.”

“All right,” Loret said, and there was a little silence. “It’s Rathe,” he added, and Eslingen heard the sound of his footsteps retreating toward the stairs.

And what in all the hells do I care which pointsman it is? Eslingen swallowed the comment as pointless, and crossed to his chest to find clean clothes. His best shirt was sorely in need of washing, and his second best needed new cuffs and collar, and the third and fourth best were little better than rags. He made a face, but shrugged on the second best, hoping the pointsman wouldn’t notice the frayed fabric and the darned spot below the collar. He finished dressing, winding his cravat carefully, and thought that the fall of its ends would hide the worst of it. There was no time to shave, but he tugged his hair into a loose queue, and then made his way down the stairs to the tap.

Rathe was standing in the middle of the wide room, the light of the true sun pouring in through the unshuttered windows and washing over him, turning his untidy curls to bronze as he bent his head to note something in his tablets. Devynck stood opposite him, arms folded across her chest, and the two waiters were loitering behind the bar, trying to pretend they were doing something useful. Jasanten, the only one of the lodgers who had his breakfast at the tavern, as a concession either to past friendship or to his missing leg, was watching more openly from his table in the corner.

“–complaint,” Devynck was saying, and Eslingen hid a grin. So she was going to go through with her threat of the night before.

“Oh, come on, Aagte,” Rathe said, but kept his tablet out. “Complaint of what? You keep a public tavern, you can hardly accuse the boy of trespass for coming here.”

“Felis Lucenan’s been told more than once that he’s not welcome here,” Devynck answered. “He comes around, makes a nuisance of himself–lies to the recruiters when they’re here, tries to get someone to take him on as a runner. I told him a moon‑month ago not to come back, and last night, well.” She fixed Rathe with a sudden stare. “I want it on the books, the times being what they are, that I don’t invite him.”

Rathe grinned, showing slightly crooked teeth. “I can’t say I blame you, at that. All right, I’ll note it down, see it’s posted on the station books. And I’ll send someone round to Lucenan’s shop to make sure she knows you want her to keep the boy at home.”

Devynck made a face, but nodded. “I suppose you have to do that, not that it’ll win me friends.”

“Fair’s fair, Aagte. Maybe it’ll make the boy a little warier, if he knows we’re taking an interest.” Rathe looked toward the doorway then. “Good morning, Eslingen.”

“Morning.” The pointsman had the look of someone who relished early rising, and Eslingen sighed. “Though I don’t usually get up til the next sunrise.”

“I’m sorry,” Rathe said, without much sincerity.

“That was all I wanted with you, Nico,” Devynck said. “People around here are starting to look sideways at me, and it’s not my doing.”

“I know,” Rathe answered. “So does Monteia. We’re doing what we can.”

Devynck made a face, as though she would say something else, but visibly thought better of it. “I hope it gets results,” she said instead, and went back to the kitchen, slamming the door behind her.

“So what can I do for you, pointsman?” Eslingen said, after a moment.

Rathe gave another quick grin. “I heard you had another bit of difficulty last night.”

“That’s right.” Eslingen took a breath, preparing himself to launch into the story, and Rathe lifted a hand, at the same moment folding his tablets.

“You don’t need to go through it again unless you want to, I got the bones of it from Adriana. And Felis is–known to us, as they say in the judiciary. We’ve had this trouble with him before.”

“Then what–” Eslingen swallowed his words, went on more moderately, “What do you need me for, pointsman?”

“Why’d I get you out of bed at this hour?” Rathe asked, disconcertingly, and Eslingen nodded.

“Not to put too fine a point on it, yes.”

“A couple of reasons,” Rathe answered, and nodded toward one of the tables by the garden windows. “I asked Adriana if I could get a bite while I’m here, you want to join me?”

“Why not?” Eslingen settled himself on the nearest of the well worn stools, tilting it so that his back rested against the cool plaster of the wall. At the moment, the sun was pleasant on his booted feet, but he knew that within an hour or two it would be uncomfortably hot. And I should find a cobbler as well as a seamstress, he added, and shook the thought away. With things as uncertain as they were in Astreiant right now, it seemed foolish to spend money on things he didn’t really need.

Rathe perched gracelessly on the stool opposite him, resting his elbows on the tabletop. “First, I wanted to ask you if you’d seen or heard anything that might have a bearing on these missing children.”

“Why ask me?” Eslingen demanded, and let his stool fall forward with a thump as Adriana appeared from the kitchen.

“Bread and cheese and a good pot of tea,” she announced. “That’s all we’ve got at the moment.”

“It looks lovely,” Eslingen said, and meant it.

Rathe nodded his agreement, and, to Eslingen’s surprise, reached into his pocket for his purse, came out with a handful of copper. “How much?”

Adriana waved away the proffered coins. “No charge–and not a fee, either.”

“Aagte’s not going to like it,” Rathe said.

“It’s on me, not the house,” Adriana answered, and winked at Eslingen. “And I won’t say who for.”

“Fair enough,” Rathe said, to her departing back, and slipped the coins back into his purse. He seemed about to say something more, reached instead for the fat teapot and the nearer of the cups. “Why ask you–lieutenant, right?”

“Right.” Eslingen accepted the cup of tea, wrapped his hands around the warming pottery. “I’m practically a stranger here, Rathe.”

“That’s partly why,” Rathe said, indistinctly, his mouth full of bread. He swallowed, said, more clearly, “There’s a chance you might notice something a local might not–someone acting odd, say, when it’s a change that’s happened slowly enough tьat everyone else has just gotten used to it.”

For a wild moment, Eslingen considered blaming the butcher’s journeyman Paas, but put the thought aside instantly. “Not a thing, and I wish I had. The neighbors are starting to look sideways at us, and I can’t find a laundress I’d trust for love nor money.”

Rathe grinned at that. “I didn’t really tьink you had, but it was worth asking.”

“Then it’s true what they’re saying–” Eslingen broke off, tardily aware of what he had been about to say. What the neighborhood gossips were saying was that the points didn’t have any more idea than anyone else of what was happening to the children.

“That we don’t have a clue what’s happening?” Rathe finished, and Eslingen saw with some relief that he didn’t seem offended. “It’s no secret. Kids’ve gone missing from all over the city, and no, there’s nothing in common among them, and no one’s found a body or seen a child being stolen, for all the talk of child‑thieves. Which brings me to the other reason I’m here. You’ve heard the rumor that the kids are being taken by recruiters?”

Eslingen snorted, swallowed a mouthful of bread and cheese. “Yeah, I’ve heard it. I’ve heard a lot of other tales, too.”

“I’m not accusing you or any soldier,” Rathe said, mildly, and Eslingen grimaced at his own haste.

“Sorry. It’s a sore point.”

Rathe nodded. “I daresay. But my question for you is, all right, if it’s not recruiters, why not?”

Eslingen stared at him for a minute, wondering where to begin, and Rathe held up a hand.

“I’ve never been a soldier, and we don’t get much soldiers’ business in Point of Hopes. Aagte’s is about the only tavern that caters to your custom. Now, in other businesses I know of, children are cheap, cheaper than adults, but not for you, it seems.”

“It takes strength to trail a pike,” Eslingen said, “and height helps, too. The same for a piece, to stand the recoil. You want a man grown, or woman, or something close to it.”

“How old were you when you signed on?” Rathe asked, and Eslingen made a face.

“Fourteen, but I joined as a sergeant’s runner. And, yes, you don’t need much skill or size–or anything–for that, but you don’t want dozens of them, either.” He took a breath. “Besides, there were three royal regiments paid off a week ago, and the recruiters can have their pick of them. No one wants kids.” That wasn’t quite true–there were regiments, like the pioneers Jasanten was recruiting for, that had a bad reputation, or lacked any reputation at all, that wouldn’t attract any but the most desperate veterans. Even the most spendthrift wouldn’t need money yet. He met Rathe’s eyes squarely, and hoped the pointsman would believe him.

“There must be jobs an experienced man wouldn’t take,” Rathe said, and Eslingen swore under his breath. “What about them?”

“Why don’t you ask Flory, there?” he asked, and heard himself turn sharp and irritable. “He’s recruiting for a company like that–and it was him who turned the Lucenan boy down flat, pointsman.”

“I will,” Rathe answered, imperturbably. “If you’ll introduce me.”

Eslingen sighed, let the stool fall again. “Come on.”

Rathe followed him easily, still carrying his cup of tea, and Eslingen wished for a moment he’d had the sense to do that himself. But it made Rathe look as though he rarely got a decent meal–the crumpled coat, worn to shapelessness over the pointsman’s leather jerkin, added to that impression–and Eslingen refused to show himself that needy. Even when he had been close to starving, years back, he had known better than to betray himself that way.

Jasanten looked up at their approach, narrowed eyes flicking from Rathe to Eslingen and then back again, taking in the royal monogram on the truncheon tucked into Rathe’s belt. He didn’t move, and Eslingen said, hastily, “Flor, this is Nicolas Rathe, he’s a pointsman–sorry, adjunct point–at Point of Hopes. Flory Jasanten.”

Jasanten nodded, still distant, and Eslingen wished he’d kept his own mouth shut. It was too late for that, though, and he contented himself with saying, “Rathe’s all right, Flor.”

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Rathe give him a quick glance, though whether it was startled or grateful he couldn’t be sure, and then Jasanten grunted, and used his crutch to push a couple of stools away from his table.

“Sit down, then, why don’t you.”

Rathe did as he was told, his expression cheerfully neutral, but Eslingen wished suddenly that he knew what the other was thinking behind that mask. “I heard you had a bit of trouble, last night.”

Jasanten snorted, looked at Eslingen. “You, too, Philip, I may want a witness of my own.”

“And will you need one?” Rathe murmured. His voice was still just as neutral, but Eslingen could almost feel him snap to inward attention.

“It’s all right, Flor,” he said again, and settled himself on the second stool. I hope, he added silently. But Aagte seems to trust him.

Jasanten nodded once, looked back at Rathe. “I saw you talking to Aagte. If you talked to her, you know what happened, and you know I’m not hiring children. So what do you want with me?”

“The same thing I wanted with Eslingen–the same thing I want with anyone here,” Rathe answered. “First, anything you might know about these kids–someone who might be recruiting them, or claim to be recruiting, anything you’ve heard.” He paused then, and Eslingen glanced sideways to see the grey eyes narrowed slightly under the bird’s‑wing brows, as though the pointsman was searching for something in the distance. “The lad who’s gone missing from the Knives Road–you’ll have heard about that, that’s the case that’s got this neighborhood up in arms. She’s twelve, got no family to speak of, just walked out of a good apprenticeship–left everything she owned sitting in her chest, and she was a girl who appreciated her things–and all I’ve got to go on is a drunk journeyman who says he might’ve seen her going south from the street, and a laundress who says she might’ve seen her, too, but going north. Now, you know as well as I do what this could mean, some madman killing or hurting for the sake of it, though so far we haven’t found bodies, and no necromancer has reported a new ghost.”

“They can bind ghosts,” Jasanten said, almost in spite of himself, and Rathe nodded.

“So they can. It’s not easy, or so I’m told. I’m not a scholar, but it can be done.”

“A madman might have the strength for it,” Eslingen said. “They’re stronger physically than they ought to be, maybe it works the same for a magist.”

Rathe looked at him, the thin brows drawing down. “Now there’s a happy thought.”

Eslingen shrugged, and Jasanten said, “That’s right, you were with Coindarel three years ago.”

Eslingen sighed–it was a subject he preferred not to think about–but nodded. Rathe cocked his head to one side in silent question, and Eslingen sighed again. “There was a man, a new recruit, out of Dhenin–he was a butcher by his original trade, in point of fact– he raped a woman and murdered her. It was pretty clear who it was, and the prince‑marshal hanged him, Rathe, so you needn’t look sideways at everyone who was paid off from the Dragons, either. But it took seven men to hold him, when they came to arrest him. And he was mad, that one.”

“I remember the broadsheets,” Rathe said. “It was a nine‑days’ wonder.” He sighed, then. “And I hope to Demis you’re wrong about madmen being magistically stronger, but I’ll check that out. It’s a nasty thought.”

Jasanten nodded, leaning forward to plant both elbows on the table. “You’ll find it’s someone like that. It has to be. No one else would have cause. Areton’s beard, I’m recruiting for Filipon’s Pioneers, and they’ve had two years of hard luck now, but I can still find grown men, even experienced men, who need a place.”

“The business,” Rathe said, with a straight face, “just hasn’t been the same since the League War ended.”

“No more it has,” Jasanten agreed, and then shot the younger man a wary look.

Rathe kept his expression sober, however, and said, “Eslingen here tells me you don’t want kids because they’re too small to handle the weapons and they don’t have skills you want. What about kids who knew how to handle horses, would you want them?”

“Ah.” Jasanten smiled. “Now that’s another matter, I admit. If you’ve got kids missing from stables, Rathe, yeah, I’d look to the recruiters. A boy with the right stars and the knack for it, or a girl, for that matter, there are girls enough born under Seidos’s signs, they could find a place if they wanted it. Or with the caravans, for that matter.”

Rathe glanced again at Eslingen, and the dark‑haired man nodded, reluctantly. “A kid would come cheaper than a trooper, and you always need people to tend to the horses. But a butcher’s brat wouldn’t be my first choice.”

“No,” Rathe agreed. He drained the last of his tea, and stood up, stretching in the fall of sunlight. “Thanks for your help, Jasanten, Eslingen–and, Eslingen, remember. If you have any trouble, anything you can’t handle, that is, send to Point of Hopes.”

“I’ll do that,” Eslingen answered, impressed in spite of himself, and the pointsman nodded and turned away. Eslingen watched him go, and Jasanten shook his head.

“I don’t hold with that,” he said, and Eslingen looked back at him.

“Don’t hold with what?”

“Pointsmen.” Jasanten shook his head again. “It’s not right, common folk like him having to tend the law. That’s the seigneury’s job, they were born to protect us–and you mark my words, Philip, this business won’t be settled until the Metropolitan gets off her ass and does something about it.”

Eslingen shrugged. He himself would rather trust a common man than some noble who had no idea of what ordinary folk might have to do to live, but he knew there were plenty of people who agreed with Jasanten–and it was, he had to admit, generally harder to buy a noble. “Maybe,” he said aloud, and stood, slowly. “I have to go, Flor.”

Jasanten looked up at him, an odd smile on his lips, but he said only, “You don’t want to waste a free breakfast.”

“No,” Eslingen agreed, and decided not to ask any questions. Good luck to you, Rathe, he thought, and went back to his table and the bread and cheese and the cooling pot of tea.

He finished his breakfast quickly enough, and returned to his room to shave, and to change shirts. He had errands to run, and he was not about to risk one of his two good shirts on the expedition–and besides, he added silently, he might have the good fortune to find a laundress who’d be willing to take his business. He tucked it back with the others in his chest, and shrugged himself into an older, coarser shirt, well aware that the unbleached fabric was less than flattering to his complexion. But that was hardly the point, he reminded himself, and slipped into the lightest of his coats. He should also probably find himself an astrologer as well, see what guidance she or he could provide– the broadsheets did well enough for entertainment, and for general trends, but these days, with the climate of the city less than favorable toward Leaguers, it might be wise to see what the stars held for him personally.

He went back down the stairs and through the main room, where Jasanten was drowsing over the remains of his breakfast, and ducked through the hall behind the bar. There was no sign of Devynck herself, but Adriana looked up as he peered around the kitchen door.

“Do you want me this morning?” he asked, and heard the girl who helped with the cooking giggle softly.

Adriana’s smile widened, but she shook her head, and tumbled a bowl of chopped vegetables into a waiting pot. “Mother will want you back at opening, but there’s no reason for you to kick your heels around here all morning. Off to fetch more broadsheets?”

Eslingen shrugged. “Probably. But I feel in need of more– personal guidance. Where does one go to get a good reading done?”

She moved away from the table, wiping her hands clean on her coarse apron. “Depends on how flush you’re feeling, now that you’re gainfully employed, Lieutenant. There are the temples, of course, but they’re expensive, and you might not want to attract the Good Counsellor’s attention just now by visiting one of his people.”

“Not particularly,” Eslingen answered. The Good Counsellor was one of the polite, propitiating names for the Starsmith, god of death and the unseen, as well as patron of astrologers, and no soldier wanted to draw his gaze, not even in peace time.

“You could go to the Three Nations,” Adriana went on. “It’s what they’re there for, especially this time of year.” Eslingen blinked, utterly confused, and she smiled. “The university students–they call themselves the Three Nations, every student claims allegiance to one of them, Chenedolle, the North, or Overseas.”

“It sounds to me as though they’re leaving out a few people.”

“Oh, the students lump Chadron and the League in with the Ile’nord, though a lot of Leaguers call themselves Chenedolliste,” Adriana answered. “And Overseas is the Silklanders and anybody who doesn’t want to be bothered with politics. It’s all political, really, a game for them and a royal pain for the rest of us.” She shook her head. “Anyway, the Three–the students have always had the right to cast horoscopes at the fairs, both the little fair, which is what’s happening now, and the great fair. It’s supposed to just be augmenting their stipend, but they tend to charge what the market will bear.”

There was a distinct note of–something–in her voice, Eslingen thought. Disapproval? Contempt? Neither was quite right. “Aren’t they any good?” he asked, cautiously, and she made a face.

“It’s not that, they’re good, all right–they’d better be, or the university would have a lot to answer for. No, it’s just that… well, the fees are supposed to be a supplement, but they tend to charge what they can get, which can be quite a lot, and the students–well, they’re students. They think well of themselves. Extremely well of themselves, in actual fact, and not nearly so well of the rest of us.” She shrugged. “They’re all right, they just get my back up–get everybody’s backs up, really, but it’s mostly because they’re young and arrogant. If you can afford it, and you want the cachet of the university, such as it is, you can go to them.”

“And otherwise?”

Adriana’s smile was wry. “Otherwise, of course, there are the failed students who set themselves up casting charts for the printers, they’re easy enough to find, or ex‑temple servants who claim they know what they’re doing, or–you get the idea.” She stopped then, tilting her head to one side. “Talk’s been of some new astrologers working the fair–not affiliated with either the temples or the university, and the word is they’re a lot cheaper than the Three Nations. Shame and all that, but a lot of people are cheering the change. It’s nothing important, it’s just nice to see the students taken down a peg or three. Loret had his stars read by one of them, and he seemed to think they knew what they were doing.”

“But where did they train? They must be connected with some temple,” Eslingen said. He’d never heard of a freelance astrologer who was any good–but then, this was Astreiant. Anything could happen here.

Adriana was shaking her head. “They don’t claim any allegiance. They read the stars, they say, and the stars belong to all gods and all women–and not just to the Three Nations. The arbiters must have approved them, or they’d have been chased off. So my advice to you, my Philip, is to save your money where you can, and see if you can find one of these astrologers to read for you.”

“And how do I find one?” Eslingen asked.

Adriana spread her hands, and the girl looked up from the hearth.

“They say they find you, if you want them.”

“Nonsense,” Adriana answered, and rolled her eyes at Eslingen.

“Well, they do,” the girl said, sounding stubborn, and Eslingen said quickly, “How do I tell them from the Three Nations?”

“They’re older, for one thing, or so I hear,” Adriana said. “I heard they dress like magists, but without badges, so look for black robes, not grey, and no temple marks.”

Eslingen nodded, intrigued in spite of himself. “I think I’ll look for them, then. Thanks.”

It was a long walk from Devynck’s to the New Fairground, almost the full length of the city, but Eslingen found himself enjoying it, in spite of the heat and the crowds. Hundreds of people jostled each other in the lanes between the brightly painted booths, or clustered in the open temporary squares to bargain over goods–spices, silks, wool cloth and yarn, dyestuffs, once stacks and stacks of beaten‑copper pots–spread apparently piecemeal across the beaten dirt. It was already bigger than the Esling fairs he had attended as a boy; what, he wondered, would the real fair be like when it was fully open?

He had no idea how the booths were laid out, though it was obvious that like trades were grouped together, but let himself wander with the crowd, listening with half an ear for the chime of the clock at Fairs’ Point. He would have to head back to Devynck’s when it struck eleven, but until then, at least, his time was his own. He found Printers’ Row easily enough, a dozen or more tables set out under tents and awnings and brightly painted umbrellas, and stopped to browse. Already he recognized some of the house names and the printer’s symbols, thought, too, that he recognized some of the sellers, relocated temporarily from Temple Fair. The sheets tacked to the display boards or pinned precariously to the sides of the tents were the usual kind, a mix of weekly almanacs and sheets of predictions according to each birth sign as well as the more general prophecy‑sheets. Most of the last dealt directly or obliquely with the missing children, and a good number of those blamed the League, but there was one big tent, its red sides faded to a dark rose, that seemed to deal entirely with politics. And impartially, too, Eslingen added, with an inward grin. Whoever sold or printed these sheets played no favorites; Leveller tracts hung side by side with sheets touting the merits of the various noble candidates. Among the nobles, the Metropolitan of Astreiant seemed to be the popular favorite–he could count half a dozen sheets openly supporting her, though whether that was genuine liking or mere proximity was impossible to tell. However, there were also a scattering of sheets pointing out the virtues of the various northern candidates. He picked out three of those, paid his demming, and stepped back to study them. Marselion’s was the least interesting, full of more bluster than scholarship, and the one supporting Palatine Sensaire was crudely done, a mere half dozen verses beneath a stock blockprint of a seated woman. But Belvis’s was something different, and Eslingen paused, frowning, to read it again. It was better printed than the others, and if the verses told the truth, Belvis certainly had the appropriate stars. He knew little about her, except that she was from the Ile’nord, but the broadsheet writer had clearly gone out of her way to reassure Astreianters wary of the old‑fashioned north. Palatine Belvis, it implied, kept to the best of both worlds; besides, the stars favored her, and Astreiant should do well to accept the inevitable. Eslingen’s eyebrows rose at that, and he glanced automatically for the imprimatur. It was there, if blurred, and he smiled, and tucked the papers into his cuff.

The clock struck the quarter hour, and he made a face, recalling himself to his real business. If he wanted to have his stars read, he would have to hurry, at least if he wanted the job done properly–and the way the broadsheets were running, he thought, I might do well to reconsider Cijntien’s offer. He glanced at another as he passed, and controlled his temper with an effort. This one openly blamed the League cities, claiming that the children were being stolen for revenge, and possibly to form the backbone of a new army that would avenge the League’s defeat. From the size of the remaining stack, it hadn’t sold as well as its neighbors, but even so, it was all he could do to control his anger. The League Wars had ended twenty years before, and had been about trade; since then, League and Kingdom had been close allies, and there were plenty of Leaguers like himself who’d shed their own blood in the queen’s service. He shoved past a stocky man who was reaching for another sheet, and turned down the nearest path between the stalls.

His anger cooled as quickly as it had flared, and he paused at the next intersection, looking for some sign of the astrologers Adriana had mentioned. He saw a trio of grey‑gowned students clustered by a food stall, but before he could consider approaching them, an older woman tapped one of them on the shoulder, only to have her coins waved away. Apparently, Eslingen thought, the students were otherwise engaged at the moment. He turned away, too, threaded his way past a group of blue‑coated apprentices, and found himself in a row of linen‑drapers. In spite of himself, he sighed at the sight of the bolts of expensive fabric, wishing he could afford a shirt from them, and then, at the end of the row of shops, he caught sight of a man in a black scholar’s gown. The sleeves were empty of badges, and he stood deep in conversation with a woman and a boy, a plain disk orrery held to the sunlight. One of Adriana’s astrologers? he wondered, and moved closer. The man was ordinary enough looking, middle‑aged, middling looks, his rusty black robe open to reveal a plain dark suit and equally plain linen. There was no temple badge at his collar, either, and Eslingen took a step closer. Even as he did, the woman nodded, and turned away. The boy followed more reluctantly, looking back as though he had wanted to ask something more. Eslingen smiled in sympathy–the woman, the boy’s mother, probably, hadn’t looked like the sort to spend her hard‑earned coins on more than the absolute necessities, which was probably why she was consulting one of the freelances rather than a student or a Temple astrologer.