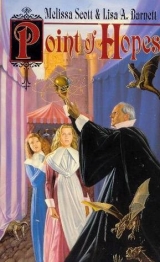

Текст книги "Point of Hopes"

Автор книги: Melissa Scott

Соавторы: Lisa Barnett

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

“I can’t burn them,” Asheri said. “I don’t have anything else half this good, not that fits me anymore.”

Monteia said, “We may be able to do something about that, Ash, since you’re losing the use of them on station business. But if b’Estorr says you shouldn’t wear them, I’d do what he says.” She looked at Rathe. “In the meantime, I’m sending to Fairs with what we have. That’s enough to make Claes arrest these bastards, and if we can catch one, maybe we can get more information out of them.”

Rathe nodded, some of the fear easing. Monteia was right about that, and Claes would act quickly enough, given this evidence. And if the hedge‑astrologers were dodging pointsmen, surely they’d be too busy to steal another child. “I’ll walk you home, Asheri,” he said aloud. “You can change there.”

The girl made a face, but nodded. “All right. But I’m not burning them. I made this shirt myself. And the cap.”

“Then put them away,” Monteia said. “And I want to see you here tomorrow morning, eight o’clock. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” Asheri said, and Rathe touched her shoulder, turning her toward the door.

“We should be able to stop them, now that we know what’s happening,” he said, and hoped it was true.

10

« ^ »

eslingen squatted beside the chest that held his weapons, considering the pair of pistols Caiazzo had redeemed from the Aretoneia. He distrusted midnight meetings, liked them even less when the messenger had failed to appear twice already, and a pistol might provide some measure of surprise, if there was trouble. He glanced at the half‑open window. On the other hand, it was a damp night, and they were going by river, which increased the chance of misfire; besides, he added, with an inward smile as he shut the chest, a pistol shot inevitably attracted attention, and he’d had entirely too much of that lately. Caiazzo probably wouldn’t thank him, either, for inviting interference in his business. He stood, and belted sword and dagger at his waist, adjusting the open seam of the coat’s skirt so that it left the sword hilt free, and glanced in the long mirror that hung beside the clothes press. The full skirts hid most of the weapon, only the hilt visible at his hip, and it was dark metal and leather, unobtrusive against the dark blue fabric.

“Are you ready, Eslingen?”

He turned, to see Denizard standing in the open door. She had put aside her scholar’s gown for a black riding suit, shorter skirt, and a longer, almost mannish coat that buttoned high on the throat, hiding her linen. She carried a broad‑brimmed hat as well, also black, and a longish knife–probably right at the legal limit–on one hip.

She saw where he was looking and smiled, gestured to his own blade. “I assume the bond’s paid on that?”

“Caiazzo paid it,” Eslingen answered, and she nodded.

“Be sure you bring the seal.”

Eslingen touched his pocket, feeling the paper crackle under his hand. “I have it, believe me.”

“Well, with a pointsman for a friend, you should be all right. Or you would be if it were another pointsman.”

Eslingen tilted his head curiously. This was the first time anyone had mentioned Rathe since the day he’d been hired. “Stickler, is he?”

“You mean you didn’t notice?” Denizard answered. “And stiff‑necked about it.” She glanced over his shoulder, checking the light. “Come on.”

Caiazzo was waiting in the great hall, talking, low‑voiced, to his steward. He nodded to the man as he saw the others approaching, and the steward bowed and backed away. Caiazzo looked at them, and nodded. “Good. I’m not expecting trouble, mind, but it’s always well to be prepared.”

“Any word?” Denizard asked, and the trader shook his head.

“Not since last night.”

Last night’s message had been a smudged slate, barely legible, delivered by a brewer’s boy, that did nothing more than set a new time and place for the rendezvous. There had been no explanation of why the messenger had missed the previous meetings, or any apology– which could just be the limits of the medium, Eslingen thought, but in times like these, I don’t think I’d like to count on it. He said, “Then maybe we should expect trouble.”

Caiazzo shot him a glance. “I trust my people, Eslingen, don’t forget it.”

“It’s not him I’m worried about,” Eslingen answered, and the trader grunted.

“Your point. But there’ll be three of us, plus the boat’s crew. That should be ample.”

“You’re coming, Hanse?” Denizard asked, and the trader frowned at her.

“Yes. I’m getting a little tired of doing nothing, Aice.” His tone brooked no argument. The magist sighed, and nodded. Caiazzo smiled, his good humor restored. “Let’s be off, then.”

Caiazzo’s boat was waiting at the public dock at the end of the street, its crew, a steersman and a quartet of rowers, hunched over a dice game, their backs turned to the other, unattached boatmen, who ignored them just as studiously. The steersman looked up at Caiazzo’s approach, and nudged his people. They sprang to their places, dice forgotten, and Caiazzo stepped easily down into the blunt‑nosed craft. Eslingen followed more carefully–he was still not fully happy with boats–and Denizard stepped in after him, seating herself on the stern benches.

“Point of Hearts,” Caiazzo said, to the steersman. “The public landing just east of the Chain.”

The steersman nodded, and gestured for the bowman to loose the mooring rope. The barge lurched as the current caught it, and Eslingen sat with more haste than dignity. It lurched again, then steadied as the oarsmen found their stroke, and the soldier allowed himself to relax. Caiazzo was watching him, and smiled, his teeth showing very white in the winter‑sun’s silvered light.

“Not fond of water, Eslingen?”

The soldier shrugged, not knowing what answer the other wanted, but couldn’t help remembering the astrologer’s warning. He’d been right about the change of employment; Eslingen could only hope he’d be less right about travel by water. Caiazzo looked away again, fixing his eyes on the shimmer of light where the winter‑sun was reflected from the current. Eslingen followed the look but could see nothing out of the ordinary, just the sparkle of silver on black water. The winter‑sun itself was low in the sky, would set in a little more than an hour, and the brilliant pinpoint hung just above the roofs of the Hopes‑point Bridge. And then they were in the bridge’s shadow, the light cut off abruptly, and Eslingen caught himself looking hard for the bridge pillars. He found them quickly enough, the water foaming white around them, and the steersman leaned on the tiller, guiding the boat into the relative calm between them. Eslingen allowed himself a sigh, and Caiazzo looked at Denizard.

“I’m not convinced, Aice, that there’s going to be much profit in this little jaunt. It may not be scientific, magist, but I’ve got a sick bad feeling about it.”

“I know,” Denizard said quietly. “So do I.”

To Eslingen’s surprise, Caiazzo laughed again. “Oh, that’s wonderful. I expected you to contradict me, Aice, or at least tell me not to anticipate trouble. The last thing I needed was for a magist to confirm my fears.”

“Well, that’s all they are at the moment–the stars are chancy, but not actively bad,” Denizard answered. “But I’d be lying if I said I was comfortable. And night meetings are never my favorite.”

“The midday ones can be just as dangerous,” Caiazzo murmured, and lapsed into a pensive silence. Denizard sighed, and folded her hands in the sleeves of her coat. Eslingen glanced from one to the other, and wondered if they were also remembering the old woman in her shop at the heart of the Court of the Thirty‑two Knives. That had been broad daylight, and he’d been glad to leave alive. He jumped as water splashed over the gunwale, and then told himself not to be foolish. The boatmen knew their business, and besides, they were none of them born to drown.

They were turning in toward the bank now, the boat rocking hard as the oarsmen fought the current, and Eslingen braced himself against the side of the boat, twisting to look toward the shore. The houses of Point of Hearts stood tall against the dark sky, lights showing here and there in open doorways and unshuttered windows, and he thought he heard a snatch of music carried on the sudden breeze. But then it was gone, and the boat was sliding up to the low landing.

“Wait here unless I call,” Caiazzo said to the steersman, and the man touched his cap in answer. The trader nodded and levered himself out of the boat without looking back. Eslingen made a face, distrusting the other man’s mood, and hurried to follow.

“Where to?” he asked, and Caiazzo turned as Denizard pulled herself up onto the low wharf.

“Little Chain Market,” Caiazzo said. “It’s not far.”

“But very empty, this time of night,” Denizard said.

“Don’t you think I know that?” Caiazzo snapped. “Why do you think I brought the pair of you?”

“Let’s hope we’re enough,” the magist answered, and Caiazzo showed teeth in answer.

“It’s what I pay you for.”

Eslingen’s mouth tightened–he hated that sort of challenge–but there was no point in protesting. Instead, he loosened his sword in its scabbard, the click of the metal loud in the quiet, and fell into step at Caiazzo’s right. The magist flanked him on the left, her eyes wary.

It wasn’t far to the Little Chain Market, as Caiazzo had said–but the street curved sharply, cutting off their view of the river. Eslingen made a face at that: they’d get no help from the boat’s crew, unless they shouted, and that might be too late. Caiazzo stopped at the edge of the open square, staring across the empty cobbles. The market was closed, the stalls shuttered and locked, shop wagons drawn neatly into corners; the winter‑sun had dropped below the line of the rooftops, and the shadows were deep in the corners. Eslingen scanned the darkness warily, but nothing moved among the closed stalls.

“Now what?” he asked.

“Now we wait,” Caiazzo said, glancing around. “And hope he shows this time.”

Eslingen grimaced again, letting his eyes adjust to the darkness. He could distinguish one patch of shadow from another now, could make out the shapes of the trestles piled in the mouth of an alley, but there was still nothing moving in the market. He heard something then, a faint sound, like feet scrabbling against the loose stones of the river streets. It could be a river rat, but he moved between it and Caiazzo anyway, cocking his head to listen. Caiazzo moved up beside him, and Eslingen glanced at him, wanting to warn him back, but the trader lifted a hand, enjoining silence. Then Eslingen heard it, too, a wordless sigh with a nasty, liquid note to it. He swore under his breath, and Caiazzo snapped, “Quiet.”

The shuffling came again, this time more clearly human footsteps, dragging on the stones, and Caiazzo turned toward them. “Who’s there?”

“For the love of Tyrseis, sieur, help me.”

Caiazzo’s eyes flickered to Denizard, who nodded.

“It’s Malivai,” she said, and it was Caiazzo’s turn to swear.

“Help me,” he said, and started toward the source of the sound. Eslingen went after him, his hand on his sword hilt.

Malivai–it had to be the messenger, a nondescript shape in a battered riding coat–was leaning against the arch of a doorway, one hand pressed tight against his ribs, the other braced against the stones. Caiazzo took his weight easily, for all the two men were of a height, and eased the man down onto the tongue of a wagon.

“Gods, Malivai, what’s happened?” He was busy already, loosening the messenger’s coat, one hand probing beneath the heavy linen.

“I’d gotten to Dhenin, almost to the city itself, I thought I was clear, but then they found me again.” Malivai caught his breath as the probing hand touched something, and Caiazzo drew his hand away. Eslingen could see blood on the fingertips and made himself look away, across the empty market. There was no sign of whoever had attacked Malivai, but he doubted that would last much longer. Almost without thinking, he drew his sword, the blade catching the last faint light from the winter‑sun.

“That’s old,” Caiazzo said. “When?”

“Three days ago.” Malivai winced again. “I told you, I’d made it to Dhenin, thought I’d lost them, but then they found me again. I got away, but one of them got off a pistol shot, that’s what you see there, and they’ve been close on my trail ever since. That’s why I couldn’t make the last meeting. I couldn’t get clear of them.”

Caiazzo nodded. “But you lost them.”

Malivai shook his head, dark braids falling across his face. “I had lost them, I wouldn’t’ve come here else, but when I tried to pass the Chain, they jumped me again. I got free, but that–” He touched his side, flinching. “–opened again. But you have to know. De Mailhac’s betrayed you.”

“Has she, now,” Caiazzo said softly, but before he could say anything more, Eslingen heard the sound of soft boots against stone.

“Sir,” he began, and Denizard broke in sharply.

“People coming, Hanse.”

Eslingen could hear the sound of swords now, and reached left‑handed for his knife. “And not to open up shop, either. They’re carrying steel, and they don’t care who knows it.”

“They probably also don’t give a damn about legal limits,” Caiazzo said. He was smiling, a toothy, feral grin that made the hackles rise on Eslingen’s neck. He had served with officers who’d had that look before; they were the sort who got one killed, or covered in glory. “I don’t see that we have a choice, do you?”

“The boat,” Denizard said, and Caiazzo shook his head.

“There isn’t time, not with Malivai.” He stooped, brought the messenger bodily to his feet, taking most of the other man’s weight on his own shoulders. He drew his own long knife with his free hand, and edged Malivai toward the mouth of the street that led to the public landing. “How many were there, Mal?”

“Three, I think, maybe four.” Malivai’s voice was weaker than before, and Eslingen risked a glance over his shoulder. The messenger was leaning heavily on Caiazzo, who was bent sideways by his weight. They’d never make it back to the boat before the pursuers appeared, Eslingen knew, and stepped between them and the footsteps that were getting steadily louder. Denizard moved to join him, her own blade drawn, and Eslingen glanced sideways at her, hoping she knew some magist’s tricks to even the odds.

A figure stepped out of the mouth of the street that led west to the Chain, and was quickly followed by two more. They all carried drawn swords, but their faces were muffled by heavy scarves, drawn close in spite of the lingering summer warmth. Eslingen shook his head, studying them, and lifted his sword. It wasn’t bad odds, even with a wounded man to protect, and the bravos were obviously concerned with keeping their identities hidden–as well they might, attacking honest people in the streets. It was nice, for once, to have the law on his side, but why was there never a pointsman around when he needed one? He killed the giddy thought, born of the anticipation of battle, and lifted sword and dagger.

The first bravo rushed him, sword raised for a chopping blow. Eslingen ducked under the attack, and drove his dagger into the man’s stomach. There was leather under the linen coat, and the blade slid sideways but caught on a lacing and tore into the man’s side. In the same moment, Eslingen brought his sword across, hilt first, and slammed it into the bravo’s face. The man dropped without a word, and Eslingen spun to face the second man, parrying awkwardly. Out of the corner of his eye, he could see Denizard and the third man exchanging thrusts, but his own opponent feinted deftly left and struck right, and the tip of his blade ripped Eslingen’s sleeve before the soldier could dodge away. Eslingen parried the next attack with his sword, and, as the man lunged again, trying to catch that blade, aimed his dagger for the bravo’s throat. It was an awkward blow, but the bravo’s own momentum drove him forward onto the blade, and Eslingen twisted away, freeing himself and his blade, the bravo’s blood hot on his hand. He turned toward Denizard, and saw her step into the second man’s attack, lifting her knee into his groin. He staggered back, blade swinging wildly, and Caiazzo shouted, “Ferran, to me!”

That was enough for Denizard’s attacker, who dropped his blade and ran. Eslingen crouched beside the dead man, wiping his hand on the skirt of the dead man’s coat, and then searched quickly through his pockets. He found a purse, and pocketed it, but there was nothing else. He shook his head–he had been hoping to find tablets, a slate, a paper, something–and turned to the other man, but Denizard was there before him.

“This one’s dead, too,” she said, and Caiazzo smiled, not pleasantly.

“Good. Anything on him?”

Denizard shook her head. “Just his purse, and from the weight of it, he wasn’t paid in advance.”

“Or this one was the banker,” Eslingen said, and held out the purse he’d taken. “There’s coin here.”

“Interesting,” Caiazzo said. “Bring it, let’s see what we were worth.” The boatmen appeared then, breathing hard, and Caiazzo swung to face them. “Ferran, help me with Malivai.”

Eslingen wiped sword and dagger on the dead man’s coat, and resheathed it, his fingers still sticky with the other’s blood. Caiazzo, still supporting Malivai, turned toward the boat, and Denizard fell into step behind him.

“How bad is it?” she asked, and the trader shook his head.

“I’ve seen worse,” he said, and the steersman came to help him, taking part of Malivai’s weight. The oarsmen followed, stolid, not looking at the dead bodies still littering the cobbles, and Eslingen trailed behind them back to the boat, wondering just what he’d gotten himself into this time. Two men dead, and another hurt–even Caiazzo would have a hard time buying his way out of this one. And I, Eslingen thought, don’t have his kind of influence to buy off my second dead man in as many weeks. He glanced at Caiazzo, but the trader’s face was closed and angry, and he decided to keep his questions for later. Together, Caiazzo and Ferran helped Malivai down into the boat, settling him against the cushions, and Caiazzo bent again over the injured man. Denizard stepped down into the boat as the oarsmen prepared to cast off, and Eslingen hesitated on the bank. For an instant, he was tempted to run, to step back into the shadows and turn and run as far and as fast as he could, until he was well out of sight and on the road north again. Then the magist looked up at him, her face curious, and Eslingen shook the thought away. It wouldn’t work, for one thing, he thought; and, for another, I’ve given my word here. And, most of all, I want to know what’s going on. He climbed into the boat and seated himself beside Denizard, letting his hand trail in the cool water, washing the blood away.

The landing by Caiazzo’s house was mercifully empty, and the boatmen vanished with the second sunset. Even so, Caiazzo and Ferran kept Malivai more or less upright on the short walk to the house– hiding an injured man from any prying neighbors’ eyes, Eslingen knew–and the trader only seemed to relax again when the doors closed behind him.

“Help Malivai upstairs,” he said to Ferran, and the steersman hesitated. “Aice will show you the way.”

Denizard nodded and started up the stairs. Ferran followed, almost carrying the messenger, who sagged visibly in his grip, and the senior steward appeared in shirt and breeches to help them. Caiazzo looked back at Eslingen. “Get yourself cleaned up, and join us. I’ll want you there.”

Eslingen nodded, for the first time really seeing the rip in his sleeve. The shirt was ripped as well: both would be difficult to mend, and expensive to replace. He sighed, and headed down the hall to the servants’ stair.

Candle and stand were waiting just inside his door, and he lit the taper from the lamp that burned constantly at the end of the hall before going back into his room. He shrugged out of his coat, swearing at the length of the tear–it ran from the edge of the cuff halfway up the shoulder on the outside of the arm, impossible to disguise–and swore again when he saw his shirt. It, too, was badly torn, and probably beyond saving. He crumpled it into a ball, and only then realized that the bravo’s sword had touched him as well. A long scratch ran along his forearm, showing a few drops of blood already drying. He scowled at that, and fumbled in his clothes chest for a clean rag. He had no desire to ruin a second shirt with bloodstains.

There was a knock at the door then, and he lifted his head. “Come in.”

One of the maidservants–Thouvenin, her name was, Anjevi Thouvenin, Eslingen remembered, and mustered a tired grin–stood in the half‑open doorway, a steaming basin in her hand. “The steward said you’d want to wash.”

She’d brought a length of bandage, too, Eslingen saw, and he took that gratefully, used it to clean the blood from the scratch. With her help, he laid a strip of cloth over the bit that was still bleeding and tied it in place, then eased himself into a clean shirt. He used the rest of the water to wash his face and hands–the right still felt sticky–and then shrugged himself into his second‑best coat. “Do you know where Caiazzo is?” he asked, and the woman grinned.

“The other end of the hall. Don’t worry, you’ll see the lights.”

She was as good as her word. At the far end of the house, a door stood open, spilling a wedge of candlelight across the floor. As Eslingen approached, he could hear voices, and then the steward came out, wiping his hands on an apron.

“Oh, Eslingen, good. He wants you.”

“I dare say,” Eslingen muttered, and stepped through the door. The room smelled of boiling herbs, a scent he recognized from the army physicians’ tents, and he wasn’t surprised to see a small pot simmering on the lit stove. Malivai lay in the great bed, propped up on pillows, a wide length of bandage wrapping his ribs. Above it, the skin was bruised and sore‑looking, and Eslingen winced in sympathy. Caiazzo, sitting on the edge of the bed, looked up at the soldier’s approach, but went on talking.

“–not as bad as we thought. Damn it, Mal, you’ve no right scaring us like that. Eslingen here just joined my household, what’s he going to think of me?”

The man in the bed managed a smile, but he looked exhausted. Caiazzo glanced back at Eslingen. “Nothing’s punctured, just a long cut along the bone, and it looks clean enough. Of course, if they were Ajanine, we don’t really need to worry about poison, that’s a Chadroni trick.”

“If they were Ajanine,” Eslingen said, “they wouldn’t have run.” He sounded more sour than he’d meant, and Caiazzo fixed him with a stare.

“And I dare say you would know.”

“The wine’s hot, Hanse,” Denizard said, from the stove, and Caiazzo looked away.

“Bring a cup, then, please.” He waited while the magist ladled a cup full of the steaming liquid–it smelled of wine and sugar and herbs and something vaguely bitter, probably one of the esoterics– and then helped Malivai take a cautious sip. “Better?”

“Some,” the messenger answered, but Eslingen thought his voice sounded stronger.

“All right, then.” Caiazzo glanced over his shoulder, beckoned to the others. “What’s going on with de Mailhac?”

Malivai took a deep breath and then flinched, his face tightening in pain. Caiazzo fed him another sip of the wine, visibly curbing his impatience.

“Take your time.”

Malivai nodded. “She–there’s a magist at Mailhac, but not of your kind, Aicelin. He seems to have de Mailhac and her people under his command.”

Denizard looked startled at that. “There was no magist there when I was.”

“You’ve been there?” Eslingen asked, involuntarily. “This year, I mean?”

“At the end of Lepidas,” Denizard answered, and shook her head. “And I didn’t see a magist there then.”

“Well, there’s one there now,” Malivai said. “And de Mailhac does what she’s told.”

Caiazzo frowned. “Why? And how did he manage that?” The messenger’s eyes slid to Eslingen, and the trader sighed. “Eslingen– Philip Eslingen–is my knife, and he probably saved your life tonight. You can speak freely.”

“It’s the mine,” Malivai said. “He–all I could get was that he promised to increase the takings from the mine, and she agreed to it. And he’s been there ever since. And as best I can see, Hanse, it’s him who calls the tune.”

“And if he promised to increase the taking,” Caiazzo said, “why haven’t I seen an ounce of it this summer?”

Malivai shook his head. “He’s not letting it leave the estate. They– he’s keeping it, but he’s not spending it, and I never saw any of it, no one did. The mine’s guarded now, never like it used to be. I’m sorry, Hanse.”

“For what?” Caiazzo said. “Start from the beginning, Mal.”

“Sorry,” Malivai said again. He took a cautious breath. “I got to the estate on the thirteenth of Sedeion, didn’t go to the house, like you told me, but went to the stables, they’re usually hiring there. Only this year they’re not, the head hostler said, for all I could see they were short‑handed. When I asked him about that, he said they’d spent too much on their time at court, and couldn’t afford extra hands–”

“Court?” Caiazzo said, and Denizard shook her head.

“De Mailhac hasn’t been in Astreiant, I’d stake my life on that.”

“The Spring Balance,” Malivai said. “The queen was on progress then, de Mailhac joined the court there.” He took another slow breath. Caiazzo reached for the wine, but the messenger waved it away. “I’ll sleep if I have much more, I have to finish first. So I asked if anyone else on the estate was hiring, said I wanted to be near my leman in Anedelle, and that I’d been able to summer on the estate before–I’ve kin there, they’ll speak for me. And I think he would have hired me, but one of the stewards came out, and when he heard who I was, told me to get off the Mailhac lands. So I went down to Anedelle then, and asked what was going on at Mailhac, and nobody seemed to know, except that there was a magist there who had de Mailhac under his thumb. Nobody likes him in the household–he’s had the maseigne selling off her goods and he’s banned all clocks from the house, which is a grand nuisance to all concerned.” He smiled then, the expression crooked on his worn face. “Then a man tried to knife me while I slept, and I’ve been one step ahead of them ever since.”

“Banned clocks?” Denizard said. “Why?”

Malivai made an abortive gesture that might have become a shrug. “Some project of his, they think, but no one knows.”

Denizard shook her head. “What sort of magist is he? Did you get a name, or whose badge he wears?”

“I never got a name–I don’t think any of them knew–but he doesn’t wear a badge,” Malivai answered. “All I know is, in Anedelle they say he has de Mailhac completely cowed–she dances to his tune–and he seems to have control of the mine.”

Caiazzo muttered something profane, fingers tightening on the wine cup. With an effort, he put it aside before he crushed it, and stood up. “All right, Mal, sleep. You should, given what I put in the wine. Philip, Aice, come with me.”

He led them to his workroom, where someone had already lit a branch of candles. Almost absently, Denizard lit a second branch of six, and Eslingen watched the shadows chase each other across the face of the clock. It was a little past two, two hours past the second sundown, and he could feel the weight of the hours on the back of his neck.

“We have to tell someone, Hanse,” Denizard said, and set the last candle in its place.

“Oh, really?” Caiazzo stopped pacing long enough to glare at her, resumed his stride in an instant. “And whom do you propose we tell? Tell what, for Bonfortune’s sake? Officially, I don’t own this estate, Aice, it’s petty treason for a commoner.”

Denizard leaned forward, planting both hands on the table. “Gold, Hanse, is the queen’s metal, it and the royal house were born under the same stars. And right now, with the star change imminent, that link is going to be stronger than ever.”

“I handle gold every day of my life–well, these last ten years,” Caiazzo objected. “And I’m common as they come. That hasn’t made any difference.”

“That’s coin gold,” Denizard said. “It’s not pure gold, they add other metals to it in the refining, precisely to keep it safe. But what comes out of the mine is pure, and it can become aurichalcum if you handle it right. That’s queen’s gold, Hanse, and they call it that for a reason. The tie between them, the queen and her metal, it’s too strong. And that’s too dangerous to just ignore.” She smiled then, not without a certain sour humor. “And after the clock‑night, I find banning clocks a very unsettling thing, don’t you?”

“You can’t think this magist had anything to do with that,” Caiazzo said.

“I don’t know how,” Denizard admitted, “but I do know this is dangerous.”

“And betraying ownership of an Ile’nord–hells, an Ajanine– estate isn’t dangerous?” Caiazzo’s voice was less certain than his words. He stopped at the far end of the room, scowling at the cold stove. Eslingen stared at him, wondering what to do. Malivai’s news was too strange, too important not to let Rathe know about it, especially if Denizard was right about the gold, and there was a link between it and the queen, and the clocks and the magist. Caiazzo would not be happy– Caiazzo would be murderous, an inner voice corrected, and reasonably enough so. You promised him your loyalty–and I promised to tell Rathe if I ran into anything unusual, too, he told himself. It may not have anything to do with the kids, but it is important. It’s too strange not to be important. He slanted another glance at Caiazzo, who still stood silent, staring into the shadowed corner beyond the stove. It would be a shame to lose his respect, Eslingen thought, not just for the revenge the trader was certain to try to exact, but because he liked the man…

Denizard’s voice broke through his reverie. “It’s become political, Hanse. And that’s a game you don’t play.”

Caiazzo dug the heels of his hands into his eyes. He stood there for a long moment, unmoving, then lowered them and turned back into the light. For an instant, he looked older than Eslingen would have thought possible. “All right,” he said, softly. “All right. Eslingen–in the morning, I want you to go to Rathe–since he got you this job, maybe he’ll give you a break on this one. Go to Rathe, tell him about this night’s business.”