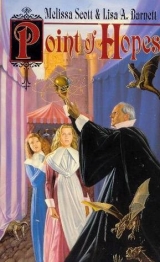

Текст книги "Point of Hopes"

Автор книги: Melissa Scott

Соавторы: Lisa Barnett

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

Eslingen shrugged. “Not much.”

He went through it quickly, concisely–he told the story well, Rathe thought, plenty of detail but all in its place. It was the same story Devynck had told, the same that Mailet had recounted, barring the butcher’s automatic suspicion of the Leaguer woman. And it sounds to me, Rathe thought, as though he handled an awkward situation rather well. He said aloud, “So why’d you pick a ‘butcher’s brat’ for your example?”

Eslingen’s mouth curved into a wry smile. “I wish to all the gods I’d picked anything else. I don’t know–there were, what, near a dozen of them, butchers, I mean, sitting by the bar. I suppose that made it stick in my mind. That and being near the Knives Road.”

Rathe looked closely at him, but the Leaguer met his eyes guilelessly. It was a plausible explanation, Rathe admitted. And I have to say, I think I believe him. Stealing children, for whatever cause–it’s just not Devynck’s style, and she’d never put up with that traffic in her house. He nodded. “Fair enough. But remember, if you have trouble here, send to Point of Hopes. It’ll pay you better in the long run than feeing me.”

“I’ll do that,” Eslingen said again, and this time Rathe thought he meant it. He pushed himself to his feet, and headed for the door.

Eslingen watched him go, impressed in spite of himself. Rathe wasn’t much to look at–a wiry man in plain‑sewn common clothes, hands too big for his corded arms, with a scar like a printer’s star on one wide cheekbone and glass grey eyes with a Silklands tilt to them–but there was something in his voice, an intensity, maybe, that carried conviction. He shook his head, not sure if he was annoyed with himself or with the pointsman, and crossed to the kitchen door, pushing it open. “Oy, Hulet, you can come out now.”

“Thanks,” the waiter answered, without notable conviction. “Aagte wants to see you.”

“What a surprise. So who is he, the pointsman?”

The other man shrugged, and went to pick up the coins that lay still untouched on the table among the scattered cards. “Nicolas Rathe, his name is. He’s adjunct point at Point of Hopes.”

“How salubrious,” Eslingen murmured.

“Oh, Point of Hopes isn’t bad,” Hulet answered. “Monteia’s reasonable, for a chief point.”

Or bribeable, Eslingen thought. His experience with the points had been minimal, but unpleasant; for all their boasting, Astreiant’s vaunted points seemed to make a very good thing out of the administration of justice. He nodded again, and stepped through the kitchen door.

Devynck was waiting in the doorway of her counting room, arms folded across her chest. She jerked her head for him to enter, closed the door behind him, then seated herself behind the table. “So Point of Hopes is already taking an interest in your exploits. Did he tell you about Andry?”

Eslingen shook his head.

Devynck snorted. “Andry’s one of the pointsmen. He’ll be along to collect your–bond, he’ll call it. Tell me what he charges, I’ll pay half.”

Eslingen lifted an eyebrow, but said, “Thanks. Is this trouble?”

“Not the bond, no,” Devynck answered, “but these kids… that could be.”

Eslingen nodded at that, thinking about his own brief explorations in the neighborhood. The people hadn’t been precisely unfriendly, the bathhouse keeper and the barber had been glad of his custom, but he’d been aware of the eyes on him, the way that people watched him and any stranger. He’d walked across the Hopes‑point Bridge that morning to the Temple Fair, to visit the broadsheet vendors who worked there, and the talk had been all of this child and that one, gone missing from their shops or homes. Half the prophecies tacked to the poles of the stalls had dealt with the question, and the lines had been five or six deep to read and to buy. “People are worried.”

“And ready to blame the most convenient target,” Devynck said, sourly. She shook her head. “I can’t see the recruiters bothering, damn it. There’re usually too many people wanting a place, not the other way round.”

“Do you suppose it’s the starchange?” Eslingen asked, and Devynck looked sharply at him.

“I don’t see how it could be, these are common folks’ kin who are going missing.”

Eslingen lowered his voice, despite the closed door. “The queen is childless, and the Starsmith is about to change signs. There is talk–” He wasn’t about to admit it was Cijntien’s idea. “–that that might be the cause.”

Devynck winced, looked herself toward the closed door. “That’s dangerous talk, from the likes of us, and I’ll thank you to keep it to yourself.” Eslingen said nothing, waiting, and the woman shook her head decisively. “No, I can’t think it. If the queen were at fault–well, there would have been some sign of it, surely, some warning, and she wouldn’t have ignored it. Besides, the gossip is, she’s barren. She couldn’t be blamed for that.”

Eslingen nodded. He was less convinced by the benevolence of the powerful–though Devynck was a skeptic by nature, certainly–but he acknowledged the wisdom of her advice. This wasn’t speculation to be voiced openly, at least not now.

“In any case,” Devynck went on, “I want to make sure we don’t have any trouble here for a while. I’ll tell Hulet and Loret, too, of course, but I’d like you to keep a special eye on the soldiers, especially any newcomers. If they haven’t heard what’s going on, they may do something stupid.”

“Like I did?”

Devynck smiled. “Not everyone has your–tact, Philip.”

Eslingen laughed. “I’ll keep an eye on things.”

“It’s what I pay you for,” Devynck said, without heat, and Eslingen made his way back into the main room.

The broadsheets he had bought that morning still lay on the table by the garden window, and he collected them, shuffling them back into a tidy pile. The one on top caught his eye. It was a petty thing, one of the two‑for‑a‑demming sort, offering predictions for the next week according to the signs of one’s birth. He had been born under the signs of the Horse and the Horsemaster, and the woodcut that covered half the page–the most professional thing about the sheet, he acknowledged silently–showed a horse and rider, and the rider held a gambler’s wheel, balancing it like a top in the palm of his outstretched hand. The fortune lay crooked across the page beneath it: chance meetings are just chance and chancy, bring chances, take chances. chance would be a fine thing! Eslingen allowed himself a smile at that, wondering if his encounter with the pointsman, Rathe, was covered in that prediction, then headed for the garden stairs and his own room.

Rathe took the long way back toward Point of Hopes, through the Factors’ Walk, with its maze of warehouses and shops and sunken roads and sudden, unexpected inlets where the smaller, river‑bound lighters could tie up and discharge their cargoes in relative privacy. He was known here, too, was aware of people slipping out of sight, staying to the edges of his vision, but they weren’t his business today, and he contented himself with the occasional smile and pointed greeting. Some of the factors dealt in human cargo–there would always be that trade, no matter what the law said or how many points were scored– but they had been the first to be searched and questioned, from the first report of missing children, and all their efforts, both from Point of Hopes and Point of Sighs, had turned up nothing more than the usual crop of semiwilling recruits. A few of the more notorious figures, the ones who’d overstepped the bounds of tolerance bought with generous fees, were spending their days in the cells at Point of Sighs, but Rathe doubted the points would be upheld at the next court session.

“Rathe!”

He looked up at the shout to see a tall woman leaning over the edge of one of the walkways that connected the warehouses at the second floor. He recognized her instantly: Marchari Kalvy, who made her living providing select bedmates for half the seigneury in the Western Reach, and owned a dozen houses in Point of Hearts as well. He admired her business sense–how could he not, when she’d had the sense to provide not just bodies but the residences where a noble could keep her, or his, leman in comfort, taking their money at all stages of the relationship–but couldn’t like her, wished he’d had the sense to pretend not to hear.

“Rathe, I want to talk to you.” Kalvy bunched her skirts and scrambled easily down the narrow stairs that led to the wooden walkway that ran along the first‑floor windows of Faraut’s ropewalk. “Will you come up?”

She was more than capable, Rathe knew, of coming down, and making a scene of it, if it suited her. “All right,” he said, and found the nearest stair leading up again.

The smell of hemp was strong on the walkway, drifting out the open windows of the ropewalk, and he could hear the breathless drone of a worksong, and the shuffle of feet on the wooden floor. There was a smell of tar as well, probably from the floor below, and he wrinkled his nose at its sharpness. Kalvy watched his approach, hands on her hips.

“So what is it you want?” Rathe asked.

“Do you want to discuss it in the street?” Kalvy returned.

“It was you who wanted to talk to me,” Rathe said. “I’ve business to attend to. It’s here, or come in to the station.”

“Suit yourself, pointsman.” Kalvy leaned against the rail, looking down onto the cobbles a dozen feet below. “It’s about Wels.”

“I assumed.” Wels Mesry was Kalvy’s acknowledged partner and the father of at least two of her children–though not, malicious rumor whispered, of the daughter who bade fair to get the family business in the end. Mesry had been arrested for pandering to a landame from the forest lands north of Cazaril. The boy in question, a fifteen‑year‑old from Point of Hopes, had claimed he was being held against his will, though Rathe personally suspected that he’d exaggerated the degree of force Mesry had used while his mother was listening.

“You know the point won’t hold,” Kalvy said. “The boy wasn’t half as unwilling as he claims–hells, how could he be, gets the chance to live in luxury for a moon‑month, maybe two, and it’s not like she was that unattractive.”

“Old enough to be his mother,” Rathe muttered.

“Sister, maybe.” Kalvy shook her head. “I tell you, Rathe, the brat was glad of the chance, losing his virginity that way.”

“She paid extra for that?” Rathe asked, and shook his head in turn. He would have liked to claim a point on the landame as well, but Monteia had flatly refused to countenance it, saying it was a waste of time and effort. She was probably right, too, but it didn’t make it any better.

Kalvy glared at him. “The landame’s childless, poor woman, that hits high as well as low. The boy had the right stars to be fertile with her, and he was well paid.”

“Practically a public service,” Rathe said, and Kalvy nodded, ignoring the irony.

“Just so.”

Rathe shook his head. “I won’t release him til the hearing–and neither will Monteia, so you needn’t bother walking all the way to the station. Think of it this way, Kalvy, I’m doing you a favor, keeping him in. This way, he can’t be blamed for any of the other kids who’ve gone missing.”

“That’s not my trade, and you know it,” Kalvy said. “You can’t blame that on me.”

In spite of herself, her voice had risen slightly. Rathe glanced at her, wondering if it meant anything, but decided with regret it was probably just the general climate. Anyone would be nervous, these days, at the thought of being linked to the missing children. “See you keep out of it, then,” he said aloud, and pushed himself away from the rail. He thought for a moment that she was going to follow him, or call after him, but she stayed where she was, still staring down at the cobbles. He went down the far stairs, past the ropewalk’s lowest doors where the smell of tar was strongest, mixing with the damp of the river.

The Factors’ Walk ended in the crowds and noise of the Rivermarket, where the merchants’ carts and pitches had spilled out onto the gentle slope of the old ferry landing. There was no ferry anymore–no need for it, since the Hopes‑point Bridge had been built fifty years before, in the twenty‑fifth year of the previous queen’s reign–but a number of the merchants brought their goods in by boat, and the brightly painted hulls were drawn up on the smooth damp stones at the bottom of the landing, watched by apprentices and dogs. Rathe skirted the edge of the market, watching with half an eye for anything out of the ordinary, but saw and heard only the usual cheerful chaos. Except, he realized, as he reached the top of the low slope, there were fewer children than usual in sight. There were a couple by the boats, a third buying vegetables at one of the cheaper stalls, and a fourth, a slight boy in patched shirt and breeches, stood talking to a man in a black magist’s robe. The magist wore neither hood nor badge, unusually, but then a man with a handcart trundled by, blocking Rathe’s view. When he had passed, the magist was gone, and the boy was running back down the slope to the river, wooden clogs loud on the stones. Rathe shook his head, wishing there were something he could do, and lengthened his stride. It was past time he was getting back to the station.

As he turned down Apothecary’s Row, he became aware of a new noise, low and angry, and a crowd gathering in front of one of the smaller shops. Squabbling among the ’pothecaries? Rathe thought, incredulously. It hardly seemed likely. He started down the street toward the commotion, and was met halfway by a woman in the long coat of a guildmaster, open over skirt and sleeveless bodice.

“Pointsman! They’re trying to kill one of my journeymen!”

Swearing under his breath, Rathe broke into a run, drawing his truncheon. The guildmaster kilted her skirts and followed. Outside the shop–one the points knew well, sold more sweets and potions than honest drugs–a knot of people had collected, hiding the group, maybe half a dozen, scuffling in the dust. With one hand, Rathe grabbed the person nearest him, and hauled back. “Come on, lay off. Points presence.”

His voice cut through the confused noise, and the people on the fringes of the trouble gave way, let him through to the knot at the center. They–mostly men, mostly nondescript, laborers and clerks rather than guild folk–stopped, too, but at least two of them kept their hands on the young man in a blue shortcoat who seemed to be at the center of the trouble. His lip was split, a thread of blood on his chin, but he glowered at his attackers, jerked himself free of their hold, not seriously hurt. Rathe laid a hand on his shoulder, a deliberately ambiguous grip, and one of the men, tall, sallow‑faced, in an apothecary’s apron, spat into the dust at his feet.

“Almost too late to save another child, pointsman, or is that part of the plan?”

Rathe set the end of the truncheon in the the man’s chest and pushed. He gave way, glowering, and Rathe looked round. “Get back, unless you all want to be taken in for riot. Now–one of you–tell me what in hell is going on. You, madam”–he pointed to the guildmaster–“is this your journeyman?”

“Yes,” the woman answered, and glared at the crowd around her. “And there’s no theft here. One of my apprentices stole off this morning in the middle of his work. When children are being stolen off the streets, what master wouldn’t worry, wouldn’t send someone to try to find that prentice? Only this lot took it on themselves to decide that my journeyman was the child‑thief.”

“Maybe you both are,” a woman’s voice called, from the shelter of the anonymous crowd.

“Well, there’s one way to find out, isn’t there?” Rathe snapped. He looked around, found a boy, thin and dark, his blue coat badged with Didonae’s spindle: no mistaking him for an apothecary, Rathe thought, that was unambiguously the Embroiderers’ Guild’s mark. He nodded to the woman who had him by the shoulder. “If you don’t mind, madam. What’s your name, child?”

The boy glowered up at him, half sullen, half scared–frightened, Rathe realized suddenly, as much by what he’d unleashed as by being caught. “Dix.”

“Dix Marun, pointsman, he’s been my apprentice for little more than a year now…” The guildmaster broke off as Rathe held up a hand.

“Thank you, madam, I want to talk to the boy.” He looked down at Marun, feeling the thin shoulder trembling under his hand. “Are you her apprentice? Think carefully, before you answer. If you’ve been mistreated in your apprenticeship, you might want revenge. But it won’t be worth it, because there are laws in Astreiant to deal with liars who send innocent people to the law.”

The child’s dark eyes darted to the journeyman who was nursing his lip and would have a badly bruised face in a few hours. That young man was damned lucky, Rathe thought, and looked as though he knew it. And if it was him the boy was running from, well, maybe it would be a salutary lesson for all concerned. He fixed his eyes on the apprentice then, his expression neutral, neither forbidding nor encouraging, refusing either to condescend or intimidate. Finally, Marun looked up at him, looked down again.

“All I wanted was to go to the market,” he said, almost voicelessly, more afraid now of the crowd that had come to his ‘rescue.’ “It’s almost the fair, I wanted my stars read, before the others. I needed to see my fortune.”

“Does your master mistreat you?” Rathe asked, gravely, and Marun shook his head.

“No. Not really. She’s hard. Sometimes she’s mean.”

“And the journeymen?”

The child’s lip curled. “They can’t help it. They think they’re special, but they’re not masters, not yet. They just think they are.”

“Do you want to return to your master’s house, then?”

“I wasn’t running away, not really.” This time, the look Marun gave the journeyman was actively hostile. “I would’ve traded my half day, but he wouldn’t let me.”

Rathe sighed. “I see. And you see these people just wanted to make sure you weren’t harmed. But are you willing to go back with them?”

Marun looked at his feet, but nodded. “Yes.”

Rathe glanced around him, surveying the crowd. It was thinning already, as the people with business elsewhere remembered what they’d been about. “I take it no one here has problems with that?”

“Give him a good hiding, madame, for deceiving people like that!”

It was a man’s voice this time, probably one of the carters at the edge of the crowd. Rathe rolled his eyes, looked at the guildmaster.

“Then, madame, there’s the question of harm done your journeyman. There is a point here, if you want to press it.”

“It was the boy’s fault, surely,” a woman called from the doorway of a prosperous‑looking shop, and Rathe shrugged.

“You should have sent to Point of Hopes, mistakes like this happen more easily when you don’t know the questions to ask. It wasn’t Dix here who beat the journeyman.” He looked back at the guildmaster. “It’s up to you, madame.”

The woman sighed, reached out to take Marun by the shoulder of his coat. “No, pointsman. An honest mistake. Let it go, please.”

“As you wish.” Rathe slipped his truncheon back into his belt. “I’ll see you to the end of the street, madame, if you want.”

“Thank you, pointsman.” She was reaching for her purse, and Rathe shook his head.

“Not necessary, madame. Despite what some think, it’s what I’m paid for.”

“Probably not enough,” she retorted, assessing shirt and coat with a practiced eye.

Rathe managed a smile in answer, though he was beginning to agree with her. “A word in your ear, madame. Keep an eye on your journeyman there.”

She nodded. “I’d a mind to it, but thank you.” They had reached the end of the street, where a pair of low‑flyers had pulled up to let the drivers gossip. She lifted a hand, and the nearer man touched his cap, slapped the reins to set the elderly horse in motion. “I count myself in your debt, though, pointsman.”

“I’ll bear that in mind,” Rathe answered, and stepped back as the low‑flyer drew to a halting stop. The journeyman hauled himself painfully into the cab, and Marun followed. The guildmaster hesitated on the step.

“I meant it, you know,” she said.

“So did I,” Rathe answered, and the woman laughed. She pulled herself into the low‑flyer, and Rathe turned back toward Point of Hopes.

The rest of his walk back to the station was mercifully uneventful, and he turned the last corner with a sigh of relief. The heavy stone walls turned a blind face to the street–the point stations, especially the old ones like Point of Hopes, had originally been built as militia stations, though they had lost that exclusive function a hundred years ago–and the portcullis was down in the postern gate, barring entrance to the stable court. He pushed open the side door, the bells along its inner face clattering, and walked past the now‑empty stable to the main door. No one at Point of Hopes could afford to keep a horse; Monteia used the stalls for cells when she had a prisoner to keep.

“The surintendant wants to see you, Rathe,” the duty‑point said the moment the man stepped into the station. “As soon as you returned, the runner said. Of course, that was over an hour ago…”

“Yeah, well, some of us had work to do,” Rathe muttered, but grinned. Barbe Jiemin at least had a sense of humor, unlike some of their colleagues. “And if it was over an hour ago, another few minutes won’t kill him. Is Monteia in?”

“Trouble?” Jiemin asked, and Rathe shrugged.

“A–disturbance–over a runaway apprentice that could easily have gotten someone killed.” Rathe ran his hands through his hair, feeling the sweat damp beneath the curls. It was still hot in the station, and the air smelled more than ever of someone’s inexpert cooking. “Guildmaster set a journeyman to bring the runaway home, and the good citizens along Apothecary Row decided this was our child‑thief.”

“Not good, Nico.” Jiemin looked down at the daybook, trained reflex, checking the day’s events. “You managed all right, though?”

“This time.” Rathe shook his head again. “Next time, I’m not so sure.”

Jiemin nodded, soberly. Before she could say anything, however, the door of Monteia’s office opened and the chief point looked out. She had removed her coat and neckcloth and loosened her shirt, but still looked hot and irritable, a few strands of hair straggling across her forehead.

“Didn’t the surintendant send for you?”

Rathe suppressed a sigh. “I just got in. And I need to talk to you. We nearly had a riot in the Apothecaries Row over a runaway apprentice.”

Monteia grunted. “Can you say you’re surprised? Come on in.”

Rathe followed her into the little room, sweltering despite the wide‑open window. There was little breeze in the back garden at the best of times, and the river breeze never reached this far into Point of Hopes.

“So what’s this about a riot?” Monteia asked.

Rathe told the story quickly, but wasn’t surprised when Monteia grunted again.

“Guildmaster should take better care of her apprentices, if you ask me. Bah, it’s not good, any way you look at it.”

“No. And there’s more.”

“There would be,” Monteia muttered.

“The butchers are blaming Devynck for their missing children,” Rathe said, bluntly. “No cause for it, I don’t think, but they’ve never liked having a League tavern on their doorstep.” He ran through that story quickly, too, and Monteia muttered something under her breath.

“Chief?”

She shook her head. “Never mind. So, you think this knife–what was his name, Eslingen?”

“Philip Eslingen, yes.”

“You think he was telling the truth there, about what he said?”

Rathe nodded. “I do.” I rather liked him, he added, silently, almost surprised by the thought, but said only, “He seems to be sensible.”

“He’d better be,” Monteia said. She sighed. “Well, we expected this, didn’t we? Or should have done. And you shouldn’t be keeping the surintendant waiting, though I wish to all the gods he wouldn’t keep drawing off my best people when they’re supposed to be on duty.” She reached under her skirts, flipped a coin across the desktop. Rathe caught it, surprised, and she went on, “Take a low‑flyer. Doesn’t do to keep the sur waiting, does it?”

Jiemin had anticipated the order, and the youngest of the runners arrived with word that a cart was waiting as Rathe stepped out into the main room. Rathe tossed the boy a half‑demming–not that he could spare it easily, but that was how the runners earned their bread, taking tips from the pointsmen–and went out to meet the driver. She was a woman, unusually, but as she leaned down to take the destination, Rathe saw she had the wide‑set, staring eyes that often marked someone born when Seidos was in his own signs of the Horse and Horsemaster. That made her stars not merely masculine but ideal, and he stepped up onto the iron bracket that served as a step with a slight feeling of relief. The low‑flyers didn’t have a wonderful reputation– half of the drivers drank the winters away just to keep warm, and the other half earned their charcoal‑money in less than legal ways–and it was somewhat comforting to think the driver had been born to her position.

“The Tour de la Citй, please,” he said. The woman nodded, straightening easily, and Rathe climbed into the narrow cab behind her, wondering if it wouldn’t ultimately have been faster to take a boat. She threaded her way through the traffic that jammed the Hopes‑point Bridge quite competently, however, and then through the maze of the Old City, drawing up at last in the cleared square in front of the Tour in no more time than it would have taken him by the river ways. He climbed out, handing over the spider Monteia had given him, and made his way across the court to the main gate.

The Tour had been built five hundred years ago as the gatehouse of the then‑walled city, and no matter how much the city’s regents and the various royal and metropolitanate officials who had inhabited it over the intervening years had tried to change it, the building still had the feeling of a fortress. Rathe’s heels echoed on the stone floors, and even the red‑coated judiciary clerks seemed chastened by the heavy architecture. At least it was cooler inside the massive walls, Rathe thought, as he made his way through the narrow, badly lit halls, and at least the regents had the sense to use mage‑fire lamps instead of oil or candles. Or maybe it was the judiciary: he didn’t have clear idea who paid for what inside the Tour.

The surintendant’s rooms were at the midpoint of the south tower and boasted two narrow windows overlooking the city square. Rathe gave his name to one of the hovering clerks and settled himself to wait. To his surprise, however, the surintendant’s voice came almost at once from behind a half‑open door.

“Ah, Rathe, good. Come in and sit down.”

Rathe did as he was told, his eyes on the surintendant. Rainart Fourie was a merchant’s son from the Docks by Point of Sighs, had begun by buying his place as an adjunct point, but had risen to chief on his own merit, as even the most grudging critics were forced to admit. His appointment was still something of a novelty–until him, the surintendancy had generally been held by gentry, the sons of landames and the like whom the queen owed favors–and he was sometimes more aware of the politics of his situation than Rathe felt was good for either him or his people. At the moment, Fourie was dressed very correctly, the sober tailored black of the judicial nobles, his haircut as close as a Sofian renunciate’s. Though that, Rathe added silently, probably had less to do with devotion or politics than with the fact that his mouse brown hair was thinning rapidly, and the fashionable long wigs would have looked ridiculous on his long, sharp‑boned, and melancholy face. Fourie lifted an eyebrow, as though he’d guessed the thought, and Rathe schooled himself for whatever was to come.

“Your former patronne sent for me this morning,” Fourie said. “It seems one of her clerk’s apprentices is missing, and she wants you to handle the case.”

Rathe exhaled. One thing about Fourie, he reflected, he always was direct. “You mean Maseigne de Foucquet?”

“Do you have another patronne?”

Rathe shook his head. He had begun his working life as a runner for the court, before he’d been a pointsman; Naudin de Foucquet had been a young intendant then, and as a judge she’d taken a benevolent interest in his career. It never hurt to have well‑placed connections, but he had not been entirely sorry when Foucquet had been assigned to the courts at Point of Hearts. Friends in the judiciary could be a liability, as well as an asset, in his line of work. “That would be Point of Hearts’ business, surely.”

“She asked for you specifically,” Fourie said.

Rathe sighed, acknowledging the ties of patronage and obligation, wondering, too, why Fourie, who usually defended his people’s autonomy, seemed willing to countenance this interference. “So who is– he, she? How old, what’s the family?”

“He’s thirteen, and his name is Albe Cytel. His mother is assizes clerk at Point of Hearts.”

So it really isn’t my business at all, Rathe thought. He said, “When did he go missing?”

“Yesterday afternoon, according to Foucquet, and I would imagine her people keep a keen eye on their apprentices,” Fourie answered.

Rathe nodded.

“He had the morning off, it was his regular half‑day, which he was supposed to use in studying. When he didn’t show up for the afternoon session, they sent a senior clerk around to his room. He wasn’t there, but nothing of his was missing, either.” Fourie looked up from his notes, and gave a thin smile. “Under the circumstances, they felt it was a points matter.”

Rathe nodded again. “It sounds like half a dozen cases I know of, two I’m handling personally. Does maseigne know how many cases there are like that in the city right now?”

“I imagine she does,” Fourie answered. “I daresay that’s why she wants you. It makes no difference, Rathe. The judge‑advocate wants you handling this case, and so do I. Can you tell me honestly you don’t want it?”

Rathe made a face. He owed Foucquet for patronage that had been very useful when he was starting out; more than that, he liked and respected her, and beyond that still, any missing child had claim on him. “No, sir, it’s not that, of course it isn’t. It’s just…” He paused and ran a hand through his hair, wondering just how far he could go. “Gods know, yes, I owe maseigne in any case, and at least she’s not asking me to drop any southriver cases for some clerk’s apprentice–” He had gone too far there, he realized abruptly, and stopped, shaking his head. “Sorry, sir. It’s been a bastard of a day.”