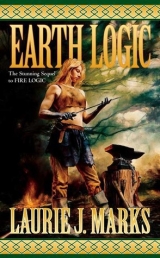

Текст книги "Earth Logic"

Автор книги: Marks Laurie

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

She reached a chaotic knot of soldiers who seemed to be trying to fight the fire that threatened to burn their barracks down, though the flames were mostly out of reach of the water they tossed at it. She found their captain and shouted at him to give up and find the source of the explosives instead, but he gave her a dazed look as though he had lost his mind or thought she had lost hers. He shouted that he had not seen Cadmar, which meant nothing.

She heard the distant horn again, and ran, and above the rising sound of chaos she thought she heard gunshots. It was a satisfying sound: at least someone had found something to do besides gape disbelievingly at the fire that exploded all around.

Rockets, she thought suddenly. Rockets, like the ones that five years ago had burned down a garrison in South Hill, supposedly invented by a now‑dead Paladin named Annis. “Annis’s Fire,” the people had called the deadly stuff that dripped out of the sky, igniting whatever it landed on with flames that could not be extinguished by water. Sand would work, but there was not enough sand in the entire city to save this garrison from burning.

Her lungs ached. Cadmar was not quick‑footed, and she should have caught up with him by now. She slowed her pace; she had lost him.

She heard a horn close by. Ahead of her were flares of ignited gunpowder, pistol shots, the shouts and cries of battle. She had run almost onto the heels of an organized company of soldiers, and they in turn had run into an ambush. She ducked into a doorway as a pistol ball plunked into wood, and finally took the time to load her weapons. When she peered out, she saw little more than shadows, but then a flaring fire nearby lit up the street in garish light and she could see. Some people lay wounded, and they soon would burn to death if no one dragged them to safety. Beyond, blades flashed as soldiers and strangers endeavored to kill each other hand‑to‑hand. One soldier, sapling‑thin and giddy with excitement, was briskly rescued from her foolishness by a big, laconic woman whose saber moved so quickly it scarcely seemed to move at all. Clement recognized both of them: the big woman was her frequent training partner, one of the best blade fighters in the garrison. The sapling was young Kelin.

“Get that child out of danger!” she cried. “She is too young for battle!”

Of course it was absurd: in the screams and shouts, the clash of blades and the explosion of gunfire, with the flames roaring in the nearby roof, Clement’s voice was like the squeak of that evening’s wayfarer bat. The sapling girl and the laconic soldier plunged side by side into the dark tangle of blade and ball. Clement ran after them.

A shout. She used her saber to cut her way through a man she presumed to be her enemy. A white face, she remembered later, garishly lit by flame, with black marks on his forehead. The flash of gunpowder, the whine of a projectile. She flung herself flat, and rolled, and saw gobbets of fire raining down, and got to her feet and ran. The sapling and the soldier had ducked into the shadows of the eaves to avoid the deadly rain. Clement coughed smoke and chased them, shouting hoarsely, but if they heard her they gave her cry no importance. Apparently, they thought they were heroes.

Perhaps these two had been following Captain Herme’s signals, but now they had left the company behind. The three women appeared to be alone in the strange night, the fighting left behind them now, the buildings here seeming empty and not yet burning. Ahead lay the garden, strangely lit with lamp flame and with–oh, Clement saw it now–the fiery rise of rockets. So this was where the rocketeers had set up their base. And did those two heroes think that it would be left unguarded? Or that they alone could end the attack? Apparently, they did.

Gasping now, for she had run across the entire garrison, Clement shouted weakly, “Beware sharpshooters!” Even as she cried out, there was a flash and the tall woman quietly folded herself up in the middle of the street, like a uniform on a shelf. Clement could already see her name, written in a company clerk’s bold handwriting. Another dead soldier with no one to replace her.

Kelin did not even seem to know what had happened. She would be eager, too drunk on excitement to be wise, imagining herself as the one who would save the garrison from certain ruin. The girl ran straight to the garden fence and climbed it. She seemed to hesitate only a moment as she looked back and realized she had lost her companion. Perhaps she was surprised to learn that death was possible after all. Perhaps she even remembered that Captain Herme had commanded her never to do anything alone. Perhaps it occurred to her that she should wait, for the rest of her company would soon break through the battle line. But there was no glory in waiting, was there?

She dropped down the other side of the fence. Clement reached through the bars to grab for the booted heel that had already begun to run across the grass, toward the garden’s fiery center where, with a shower of sparks, another rocket went arcing across the sky. Clement watched her go. She dared not shout after her, and could only watch, clenching the iron fence like a prisoner, as Kelin all but flew to the garish ritual. A half dozen giddy people seemed to dance and bow, with flaming lucifers in their hands, and then they all went dancing back. With a deep sound like a rushing wind or waterfall, the light flew fiercely up into the sky, trailing sparks and a gently glowing smoke. And then Kelin was on them, swift, blithe, oblivious. Perhaps she managed to injure one–it was hard to tell in the tricky light–and then she was cut down.

Clement groaned as though the swordcut had entered her own pounding heart. Her eyes ached with smoke and from peering into the shadows. The rocketeers’ dance went on: in and out, matter‑of‑fact. Another rocket burst into the sky.

Clement’s head began to clear. She had gotten a few good breaths of air, perhaps, or perhaps she was simply too inured to battle to weep for long. She had begun to plan the attack on the rocketeers before she even realized it, and when Herme’s company, now missing two members, came running down the street, she was ready to tell them what to do.

Hours later, Clement finally located Cadmar. Having himself never gone near the battle, he chastised her for her hotheadedness. She had commanded the company that eliminated the rocketeers, and had, after all that, emerged unscathed. Only Cadmar, whose temper came mostly from envy, could have failed to appreciate what a hollow victory it was.

When he had used up his anger, he sent her to locate Commander Ellid, a task that wasted what remained of the morning. Clement found the garrison commander at last, standing before the smoking ruin of a barracks, with her hair singed and her face black with soot. Clement would not have recognized her if not for the insignia on her hat and the messengers that circled her like bees around their hive. Ellid was a strong‑willed, short‑tempered old veteran who enjoyed good food and had never forgiven Cadmar for driving away her excellent cook. But today she seemed relieved to learn of the general’s safety.

“He was fighting fires all night,” said Clement. “Now he’s visiting injured soldiers in the infirmary. He’s no worse hurt than you are.”

The commander looked ruefully at her singed uniform. “A few burns.” Her voice was a hoarse rasp; like Clement she had been breathing smoke and screaming orders all night. “The general,” she added, “was supposed to go to safety should the garrison be attacked.”

“Surely you know that he will never be so prudent. But it was my duty to escort him to safety, if any safety could have been found last night, and I could not even find him, and ended up in danger myself. It’s been a stupid night.”

“That’s true enough. Well, it’s over, eh?” Ellid lifted her head and surveyed the smoking ruin of her garrison with swollen, red‑rimmed eyes. “Though I can’t believe what I see,” she muttered.

“The refectory is still standing, anyway, though the kitchen is gone. The general requests that you meet him there. Surely the cooks will soon manage to produce something to eat.”

Ellid made a soldier’s gesture, simultaneously acknowledging, agreeing to, and delaying compliance with an order. One of her lieutenants was approaching, and she turned to see what he wanted.

Again, Clement limped slowly down cobbled streets turned black with ash, past smoking ruins of charred timbers. Soldiers sprawled here and there, the dead difficult to distinguish from the exhausted living, all dressed in ashes and masked with soot. At a well where the ground was still awash from the spilled water of a fire line, some soldiers took turns dunking their singed heads into a bucket of water. Clement joined them, took a turn with the cake of soap, and looked up from rinsing the grime away to find the gathered soldiers giving her demoralized salutes. One of them took her hat and polished the soot from her insignias. “Lieutenant‑General, the Lucky Man says anyone who sees you is to tell you he’s in the general’s quarters.”

She went there. Gilly had taken over Cadmar’s table, since Commander Ellid’s quarters had burned to the ground. He and the garrison clerk had opened the log and rosters, which, being singed in places, apparently had been snatched out of the flames. Soldiers came and went, to tell the clerk and secretary the names of soldiers dead or wounded. Soon it would be Clement’s turn to deal with that dreadful paperwork. Perhaps this would be the disaster that finally forced Cadmar to close a garrison for lack of soldiers. And then the Paladins would realize the Sainnites’ secret weakness.

“Come with me,” she said desperately to Gilly.

She brought him his cane and helped him to his feet, and walked him past a newly arrived soldier, who was so tired he could scarcely tell the clerk the name of his fallen comrade.

As they walked down the hall, Gilly, leaning more heavily than usual on his cane, said admiringly, “The clerk actually ran into a burning building to save the records. If she hadn’t, we would be in quite a tangle.”

Clement looked at him in disbelief. Gilly’s ugly face twisted with an ugly grin, and Clement began to laugh. Laughter whooped out of her aching chest: mad, mysterious. She laughed until she choked, and Gilly, still grinning his dreadful grin, pounded her too roughly on the back. She sopped up the tears that were running down her face. “Gods! Don’t do that to me again today! It’s been a hellish night!”

Gilly grunted. “The soldiers think we were attacked by magic.”

“Cadmar did too, until I reminded him of Annis’s Fire. They say that Annis was a genius with explosives.”

“Was?”

“Apparently, even her family believes she’s long dead, accidentally killed by Paladins. Her rockets and her fire haven’t been used since she died, but I guess she told someone her secret after all.”

They found Cadmar holding the clenched hand of a woman whose face had been burned to the bone. The infirmary stank of burned meat and sounded like a nightmare. The medics went around with smoke pipes to quiet the agony of the ones they judged were dying, but those that might live continued to scream.

“By the three gods!” cried Cadmar in a fury, once they were outside. “The Paladins will regret this cowardly attack!”

They had nearly reached the refectory before Cadmar had raged himself into silence. Clement then ventured to say, “Commander Ellid will have enough to do just solving the practical problems of recovering from this attack. Let me handle the counter‑attack. We must have a strong reaction–an intolerable one.”

Cadmar said, “You’ll need a detachment to serve under your command.”

As they entered the refectory, Gilly muttered to Clement, “You think the Paladins won’t target you now? You could be dead before midsummer.”

“I’d rather be dead than have to deal with the duty roster after this disaster.”

“What kind of revenge do you have in mind?”

“I’ll take their children,” Clement said, “and raise them to be soldiers.”

Gilly looked stunned. But later, as they ate gummy gray porridge with Ellid, her lieutenants, and some of her captains, and Cadmar’s resilience began to display itself in energetic conversation, Gilly leaned over to Clement and said softly, “It’s brilliant! But if we start stealing children, you’ll put that courtesan of yours out of business.”

The commanders were piecing together a chronology of the night’s events, all of which Clement already knew or had surmised. Cadmar announced that anyone who knew anything about the attackers was to be sent to Clement. They decided to go as a group to view the sites of the heaviest fighting.

The ten of them made slow progress across the garrison. Teams of soldiers methodically sorted the living from the dead, and the streets that before had been littered with bodies were now busy with exhausted soldiers being herded to food and shelter, injured soldiers being carried to the infirmary, and old veterans with buckets of soapy water, washing the faces of the dead so they could be identified. They passed an improvised paddock, where hysterical horses rescued from the burning stable were being soothed and treated. Shock had already given way to efficiency.

Gilly was obviously in pain, and seemed glad to have to pause again to let some litter bearers pass. He was accustomed to pain, and it only seemed to give his sharp mind a certain ruthlessness. He said, “This troubles me, this attack. It’s not like the others. It goes against Mabin’s directives, and the local Paladins’ own disinclination to do anything that might lead to retaliation. They pride themselves on their long view, don’t they? And on their caution.”

Cadmar and Ellid had paused ahead of them, and Captain Herme was narrating how the well‑armed attackers had lain there in ambush and had–he seemed reluctant to admit it–defended their position with determination and courage. Some ten of their bodies lay tossed contemptuously into a pile. Did the officers care to view them?

“What for?” asked Cadmar.

But Gilly had already limped over to the pile of dead bodies. “They are so young,” he said. “This also is not right.”

Clement stopped looking at the wounds and turned her attention to the faces. “And Paladins sneer at us for sending children to war,” she said.

“What is that on his forehead? Wipe off his face, will you?”

Clement had nothing to wipe anyone’s face with, but Gilly produced a voluminous handkerchief, and she bent over to smear away the soot and gore from the young man’s forehead. What remained was a mark, painted in what appeared to be black ink. Gilly examined it silently and intently, and then stood back, looking first bemused and then unnerved.

He said to Cadmar, who grimly waited, “I would guess these fighters all have the same mark on their foreheads. It is a glyph, the one that is called the Pyre, or Death‑and‑Life.”

“What does it mean?” asked Cadmar.

Gilly shook his head, his ugly face unreadable now. As they resumed their progress, Clement tucked a hand under his elbow to give him some help in walking. She said, “You suspect something.”

Gilly said, “Councilor Mabin herself wrote in her book that she was at Harald G’deon’s side when he died. She observed that he did not vest a successor. These rumors we’ve heard about a Lost G’deon–Mabin has to be certain they are untrue.”

“So?” Clement felt nearly hysterical with exhaustion, and strangling Gilly seemed better than listening to him recount irrelevant history.

“So I must conclude that these people who attacked us last night could not have been Paladins. That glyph on the dead man’s face is the sign that used to be carried through Shaftal whenever an old G’deon died and a new one was vested: Death‑and‑Life, meaning that the G’deon burns in the pyre and yet the G’deon lives. Mabin would never allow her people to display that sign.”

Clement was silent. She had paid little attention to the rumors of a lost G’deon, and was trying now to remember when she first had heard them. It had been less than five years ago, but Harald had been dead for twenty. “You think these people who attacked us believe Harald vested someone before he died?”

“That big woman who supposedly pierced Councilor Mabin’s heart with a spike–perhaps they are fighting for her.” He paused, then said one more word, but it reverberated in Clement’s scrambled thoughts. “Fanatics,” he said.

Later, they stood together in the scorched garden, looking down at the slender soldier who had run in such glad foolishness to her own pointless death. The soldiers had separated Kelin’s body from the others, had wiped the soot and blood from her young face, and had covered her ugly wounds with a blanket. But they could not put the vibrancy back into her slack face, or the liveliness back into her blank eyes. Clement looked away from the girl’s body. Gilly fumbled for his sooty handkerchief. He should haveknown better than to become fond of a young soldier,Clement thought bitterly. All Sainnite children die in war. As fast as we send them into battle, they die. We might as well just kill them when they’re born and save us all the trouble of raising them.

Part 2

How Raven Became A God

When Raven was young, he had three friends: a grasshopper, a sparrow, and a wolf. They all were restless troublemakers, the shame of their clans and the scourge of their tribes.

One day, the bird gods appeared to Raven and said, “We have been watching you a long time, and we think we might make you into a god. But first you must make something that has never been seen before, to prove to us that you are clever enough to be a god.”

Of course, Raven wanted to be a god, but he had no idea how to make something that had never been seen before. So he asked his friend the grasshopper for advice. The grasshopper said, “Well, I know one thing that has never been seen before: it is the soul of my clan, that lies at the center of the village, in a hut that nobody enters.”

Then Raven went to the sparrow for advice, and the sparrow said, “Well, I know one thing that has never been seen before. It is the soul of my clan, that lies at the center of the village, in the hut that nobody enters.”

Then, Raven went to the wolf for advice, and the wolf said, “Well, I know one thing that has never been seen before. It is the soul of my clan, that lies at the center of the village, in the hut that nobody enters.”

So then Raven called together his friends. He said, “I have thought of a wonderful joke. We will go to each of your villages and make a great noise, and they will think they are being attacked. They will all run about like the ant clan, and we will hide in the woods and laugh at them.”

They all agreed that this was a fine plan. So they waited for the dark moon, and on that night they all met outside the sparrow’s village. They each had brought all the whistles and rattles they could find, and they spread out along the edge of the village and each commenced yelling and whistling and shaking their rattles. Soon, the sparrow warriors came running out of the village to find their enemy, while the sparrow elders and children hid in the huts. The three friends all slipped into the woods, laughing. But Raven sneaked into the center of the village, and found the hut that has no door, and with his claws he cut a slit in the wall and slipped in. There in the hut he found the soul of the sparrow clan.

Now, no one except Raven has ever seen a soul, so I can’t tell you what the soul looked like. But Raven bit off a piece of it with his sharp beak and put it in his satchel. Then he slipped out of the hut and sewed up the opening he had made in the wall, so no one would notice, and he went and found his friends in the woods. “Wasn’t that fun!” he said. “Let’s do it again, this time at the grasshopper clan.”

So they did it again, at the grasshopper clan and then at the wolf clan, and each time Raven sneaked into the village and stole a piece of the clan’s soul. But after the wolf warriors had run into the woods looking for their enemy, they encountered the sparrow and grasshopper warriors, who were all searching the forest. They each thought that the other clans had banded together against them, and a huge battle began.

In the morning, Raven’s friends found him in his camp, where he lived by himself. They all were sick with horror. “The warriors of our people have all killed each other, and now our clans will hate each other for many generations!” they cried.

But Raven didn’t care. He had a pot of stew and he offered each of his friends some, but they were too upset to eat. So Raven ate it all himself, and his friends went away in disgust and never talked to him again.

Now, the stew was made out of the pieces of soul the Raven had stolen from each of the clans. After a while, he started to have a stomachache, but he endured the pain, for he wanted very badly to be a god. And then at last he put piece of leather on the ground and he defecated on it, and there lay a raven’s turd made of the digested souls of the three clans. No one has ever seen a soul‑turd except for Raven, but you can imagine it wasn’t pretty to look at.

Raven packaged up that turd and took it to the gods. “Here you go,” he said. “Here is something that has never been seen before.” The gods all looked at the turd, and then they looked at each other, and finally one of them said, “I can’t believe that you have done this! But we have no choice except to make you a god. Considering all the havoc you have wreaked, I think we will make you the god of death.” And that is how Raven became a god.

As for the turd, it was so disgusting that they buried it. A year later, Raven went back that way, and where the turd had been buried, a new clan had risen up out of the ground, and were living in a new village. They farmed and sang love songs like the grasshopper. They were clever and hardworking like the sparrow. And they were loyal and brave as the wolf. Raven took a special liking to them because his turd was the soul of the clan. They were the first human people.

Chapter Eight

The farm family, having been shouted out of their beds, huddled together as far as they could get from the heavily armed, impatient soldiers that crammed the dark parlor. The farmstead’s many children had been made invisible behind a fortress of resolute adults. But one man, cut out from the crowd with a screaming child in his arms, faced down the hardened fighters that surrounded him. “You will not take the child,” he said.

By the flickering light of the lantern held up by the signal‑man, Clement distantly examined the stubborn father. He did not seem old, but he was desiccated, his hair molting, his eyes set in shadowed hollows, his body sagging as though his muscles were coming detached from his bones. To admire his hopeless courage was a poor strategy, but as a nearby soldier eagerly lifted his club, Clement forestalled him with a raised hand. She said quietly to the man, “Your daughter’s last memory of you will be of your death.”

The man’s hand protectively cupped his daughter’s skull as she hid her face in his shoulder. Obstinately, fearlessly, he said, “You will not take her!”

They had just one night to round up forty children–Clement could waste no time in argument. She began to lower her upraised hand, and like a puppet the soldier again lifted his club.

“Wait!” An old woman stepped into the light, jerking herself loose from the hands that reached out to restrain her. “Take me instead.”

“No!” cried the farmers. But the old woman, trailing a blanket snatched from her bed, gestured dismissively at them.

“Take the old woman,” Clement said to the soldiers.

They laid hands on the old woman; they hurt her until she cried out. A grinning soldier pricked her throat with a dagger.

Now the little girl’s father looked panicked. Good. Clement said, “We’ll kill the old woman first. And we’ll kill the rest of your family, one at a time. And with all of them dead, you’ll still lose the girl.”

The man said dully to his hysterical daughter, “Davi, you go with these people. Be a brave girl.”

“No!” she shrieked. “They scare me!”

Clement jerked the girl out of the man’s grip, and handed her, flailing and screaming, to the soldier behind her. The father uttered a shout and flung himself after her. A sharp crack on the head, and he fell. The old woman, released, cried bitterly, “We will never forget this!”

Out in the yard, which was crowded with war horses, they dumped the screaming child into the closed wagon, where her cries revived those of the other children previously snatched from other farms where other farmers had offered the same outraged, disbelieving resistance. It had become a routine. So far Clement had managed to convince the families of her seriousness without killing anyone. In Sainna, the parents would have begged her to take the children so they’d have one less mouth to feed.

“That’s fourteen kids,” said the sergeant in charge of guarding the wagon.

“Mount up,” said Clement.

“Mount up!” cried the captain, and the signal‑man led the way, with his lantern.

It was a gorgeous, soft night: spring’s swift bloom had given way to summer; winter’s bitter winds and drifting snow were nearly impossible to remember now. Stars crowded the sky, and Clement could almost imagine what the Shaftali found to love in this unforgiving land. The children’s muffled cries settled to whimpers, and Clement could hear bird calls and a din of frogs at the pond they were passing. She pretended to herself that she was serene enough to appreciate this lovely ride. Forty children for forty dead soldiers: a grueling night.

She had let the people of Watfield and the surrounding countryside wait for retribution. Immediately after the fire, the local Paladins had been mustered, and for a long time had hovered just outside the city, where they made themselves a nuisance by interfering with lumber deliveries. Occasionally, Ellid, to boost morale, had sent out a company of angry soldiers to fight with them. When Cadmar, Gilly, and a select company of soldiers had ridden out to begin the tour of the garrisons, they reportedly had enjoyed a brisk clash of arms as they passed through the Paladins’ perimeter. Now, nearly a month after the fire, the Paladin alert had relaxed. That night, Clement and her detachment had slipped out of the city unnoticed, and so far had done their work unhindered.

Clement could not predict how long it would take for the Paladins to converge on them or how much the presence of children would inhibit them from attacking. The attackers would probably try to force the soldiers to abandon the wagon, and Clement had trained the detachment accordingly. The soldiers had enjoyed the playacting, which was easier and more interesting than clearing rubble. Clement had needed the distraction, for she felt that she lived in the shadow of doom, and Gilly was not there to jolt her out of her dark mood with his acerbic commentary.

They rode into an empty farmstead. The soldiers searched the house and reported bed covers flung back and clothing tossed about. After they were on the road again, the captain rode up beside Clement and said, “I suppose there’s a farmer galloping ahead of us on a fast horse.”

In the past, farmers could have warned their neighbors or summoned help using bells that were hit with iron poles, but they had long since been broken of that habit by Sainnite retribution. Clement said, “Farmers don’t have fast horses. They’re probably running from farm to farm in relay. Let’s hurry our pace, skip a couple of farms, and see if we can get ahead of the alarm again.”

By this method, Clement’s detachment managed to acquire a couple of more children, but then they found only empty beds again.

“Signal fire,” the captain said in disgust.

Clement had also noticed light flaring on a hilltop, and knew that soon several more scattered hilltops would be aflame. “Return to Watfield,” she said. “Quickly. No need to spare the horses now. And let’s hope no one in town notices the signals.”

*

In the city, her soldiers broke down the doors of two and even three houses at once. Even though Clement insisted that they take only one child from each household, the total quickly mounted by ten, fifteen, twenty more children before the forewarned parents began hiding their children from the soldiers in cellars, woodsheds, and attics. The soldiers, forced to extricate cowering, hysterical children from dark and cluttered places while holding back and sometimes fighting desperate parents, began to lose their tempers. Clement, supervising from the street, heard reports of blood spilled, of a child injured. She listened to the city rousing: dogs barked as a ripple of door pounding and warning shouts spread down the streets from her operation.

“How many recruits do we have?” she asked the sergeant in charge of guarding the wagon.

“Recruits!” He laughed as though he thought she was joking. “Thirty‑six.”

“Close enough to forty. Signal‑man! Retreat to garrison!”

The night was no longer quiet. From the water gate Clement could see a distant beacon, its flames subsiding now but still bright in the distance. The roused city echoed with the angry clangor of pots being banged. A mob had gathered at the garrison gate, and all watches had been mustered to guard the wall. Periodically, Ellid’s bugler sounded a signal, which received an orderly answer from each of the scattered companies. The signals told Clement that there had been some few skirmishes, but so far no emergencies.

Clement was feeling very tired. The signal‑man told her the time; soon dawn light would start to extinguish the stars. Clement rubbed her face vigorously and shouted at the stable sergeant, “How long does it take to change horses?”

“It’s hard to get the harnesses buckled in the dark, Lieutenant‑General,” he said apologetically.