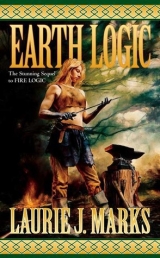

Текст книги "Earth Logic"

Автор книги: Marks Laurie

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“Thank you,” she said distantly. She felt like she was falling; Lomito was far away, and Karis was even farther. “Safe journey,” she said to him. She picked up her gear, and walked away.

From one crowded Juras camp to the next, as the rain gradually let up and the earth began to warm, Zanja traveled, told her story, saw the people institute J’han’s plan for killing fleas and preventing infection, and traveled on. It took fifteen days for the clouds to break apart and drift away. That day found Zanja alone as the vivid green plain unrolled before her feet like a bolt of green silk. Blue sky met green horizon, featureless and flat in all directions, and only Zanja’s own shadow could tell her which way she was going. She had spent much of her life alone, but never had she been without a tree or hill to inform her of her place on the world. Now, as she walked, her interior spaces remained empty as the plain and the sky: disconnected, all her ties illusory, all her hopes a vacancy. She became convinced that Karis was indeed dead, and wept as she walked, dazed by sorrow, dazzled by light, through a thick steam that began to rise as the sun warmed the wet sand.

The air even smelled of death: a faint, sweet stink that gradually became overpowering. She wiped her eyes and looked around herself, for she had gotten completely disoriented and might have been walking in aimless circles for all she knew. Ahead of her, a sturdy caravan rose out of the mist, still and derelict as a wrecked ship lying askew on the shore. A broken axle, Zanja thought, but her nose told her that something worse than a mere mischance had befallen this house on wheels.

When she drew close, she saw the remains of the dray horses, dead in their traces, half eaten by scavengers before the winter cold froze the remains. Now, fat flies blew up in a cloud as Zanja approached, and vultures fled in great, ungainly hops through the calf‑deep grass. The message of the dreadful scene was not too hard to read: the horses, trapped by the broken wheel, had died of starvation with grass just out of reach. But what of their driver?

The caravan door was tilted skyward, and the wood had swollen from the long rain. She levered the door open with her knife blade, and then fell back, gagging from the stink. She caught only a glimpse of what lay within: a man’s dead body, rotting in a tangle of ruined trade goods. Holding her nose, she kicked the door shut, and fled beyond range of the smell to collect herself. No wonder her very thoughts had been infused with the stink of death.

In the warmth of the afternoon, the steam began to burn away, and Zanja noticed that underfoot, beneath the shelter of the grass leaves, a second plant was thriving and had almost completely matted over the sand’s surface with its small, lobed leaves. Looking closer, she saw the tiny green buds swelling. In a few more days, the sand would be decorated with flowers. She spotted a small eruption in the sand, and there emerged a fat black bee the size of her thumb tip. He basked in the sunshine after his mead‑sipping winter underground, buzzing his wings occasionally, no doubt planning what he would do when the flowers came into bloom.

So Karis now sat, somewhere on this same empty plain, with the sunshine in her face, thinking how to restore her life after the ravages of illness and the hardships of that winter. Zanja sat back on her heels, beside the sleepy bee, and let her fear and sorrow go. She had chased Little‑Biting‑Dust across the plain, from one Juras camp to the next, and in each camp she had found fewer sick and greater surprise at her urgent message. Now, she had reached the end: a dead man, a peddler, with illness carried in his trade goods, and perhaps in stowaway rats as well. Here the plague’s journey had finally ended.

She slept for a while beside her buzzing companion until she was awakened by goats bleating in the distance. She followed the sound to the flock, which meandered its lazy way across the grassland, driven, or perhaps merely followed, by a loose cluster of heavily laden Juras. The giants lightly carried their children, their early kids, their furniture, and their very houses upon their backs. When they spotted Zanja’s approach, they stopped dead in their tracks, staring. One of them said, “Look: it is a very small person made of shadow.” Some rather ostentatiously loosed their clubs, which they generally used only to defend the goats from predators, but they relaxed quickly enough when Zanja gave proper greetings to the headwoman. She explained that they should give wide berth to the wrecked caravan in the distance, and eventually, when she had explained enough, they gave her some provisions, and loaned her a small ax, which she promised to return when she found them again at the gathering of the Juras.

With this ax she chopped apart the rolling mausoleum and used its wood for fuel with which to build a pyre. By noon the next day only black skeletons of wood and bone remained.

Zanja’s boots had fallen apart at the seams, and she arrived at the gathering of the Juras barefoot. She had let her long hair out of its braids to dry, and had never bothered to plait it up again. As she made her way among the gathered flocks of goats, where many a goat lay in labor or nursed her newborn kids, the old does kept a close and hostile eye on her. At the center of this tremendous goat gathering lay the camp, where several hundred goatskin tents stood like tan sails on a green sea. Here, the Juras people sat in the sun, and talked, and sang, and roasted fresh meat on open fires. For once, it was not goat, but buffalo, and it smelled delicious. Like the goats, the people turned in astonishment to watch Zanja pass.

When she returned her borrowed ax, the children of that household followed her through the camp, asking question after question and begging to be allowed to touch her hair. They trailed behind her like a pack of enthusiastic but clumsy puppies, until at the very heart of the camp they suddenly disappeared. She lifted her gaze at the sound of a familiar, hoarse croak. A lone raven had landed on the tip of a tent pole. “Raven, is Karis here?” she cried.

“Follow me,” said the raven.

He led her to a tight circle of tents, where she found a big Juras woman sitting among her cousins, with her hair cropped short and tied in tiny bunches all over her skull. Karis’s face had gotten more alien as well: pale and hollow, gaunt with illness. She listened attentively to an elderly woman as though she could understand her, while at her shoulder Lomito struggled out a framework of Shaftali words, with all the heart stripped out of them.

Zanja knelt behind Karis and asked quietly, “Is this your mother’s relative?”

“Her aunt,” Karis said, without turning her head.

Zanja took over the translating, which seemed a relief to Lomito. The old woman said, “Do you know, there are some goats that cannot be watched. The moment the herders turn their back, this goat sets forth from the flock. The wise goats call to her to come back, and warn her that there are places without water, and places where hungry lions roam. But they cannot convince her, and so we find her later, dead or injured. And if she lives to be returned safely to the flock again, she sets forth again, sooner or later.”

Karis was nodding. “Yes, yes,” she said in the Juras language, which was probably the only word she had learned.

“My sister’s daughter was like that goat: restless, heedless, deaf to advice. After she came into her womanhood, she only grew worse: she often disappeared for days at a time, and nothing could keep her at home, or make her contented with her mother’s fine flock. At last, she disappeared entirely, and never was seen again.”

“Was it in the spring?” Karis asked. Karis knew all about the springtime restlessness that sets the feet to roaming.

“It was in the spring, during the gathering. I remember that Man‑in‑Rolling‑House came, and we traded winter wool for fat and sweets to make a feast. Perhaps Kasanra went with him, hidden in his house. My sister Karisho had no other daughters, only sons, and so the goats went to my other sister’s eldest daughter, Kamole. Kamole was born before Kasanra disappeared.”

“Do I look like Kasanra?” Karis asked.

The woman studied Karis’s face. “I think you look as your mother would have, had she not killed herself with foolishness. You look somewhat like Kamole, who now has three children, and her eldest bore a child this winter. Here is Kamole now.”

Karis murmured, astounded, “My cousin is a grandmother?”

Everyone in the circle was rising to their feet. Zanja stood up as well, but Karis only looked up politely as a big, angry woman came into the circle. Zanja, her hand on Karis’s shoulder, said, “This woman is your enemy, I’m afraid.”

“She does look grim. You should tell her they carried me here in a litter, and I am too weak to stand.”

“What are you doing here, then?” Zanja asked, appalled.

“Oh–trying not to waste any more of my life. Look at me: no goats, no grandchildren …” She was smiling, but her hand closed over Zanja’s as Kamole towered over her. The supposedly peaceful Juras told tales of wrestling matches between rivals, and it was rivalry over goats as often as it was over lovers. Kamole certainly seemed to be in the right mood, and Zanja hoped she wouldn’t have to draw her dagger in Karis’s defense.

Zanja said in the Juras tongue, “Karis apologizes that she is still too ill to stand.”

Kamole gave Zanja a startled look, as though she were a goat that had abruptly spoken. “What are you?” she demanded.

“I am a crosser of borders, a speaker of languages, a reader of signs. I am Zanja na’Tarwein.”

“Huh,” said the woman. “The gathered Juras talk only of the sham‑redaughter of lost Kasanra. You must be the one of her shushanwho tells stories.”

Zanja said to Karis, “Well, she is unimpressed with us, and implies that anyone who admires us is frivolous.”

“What’s to admire?” said Karis. “I am too weak to stand, and you don’t even have shoes. But perhaps you’d better reassure her that I don’t want her goats.”

“And insult her by implying that her goats are not desirable?” Zanja spoke to Kamole. “Karis says that everyone has spoken highly of the daughter of her mother’s sister, whose goatherd is the finest in the southern plain. She is glad to finally meet you.” She instructed Karis, “Look glad. Clasp her hand.”

Karis did, and everyone but Kamole relaxed and sat down.

Kamole said, “Why have you come here? We prefer that the people of the forest lands leave us alone.”

Karis said, “This illness we have chased here would have killed so many Juras that perhaps the tribe might not have recovered.”

Kamole replied obstinately, “Every other stranger brings grief to the Juras. We have not forgotten how the forest people brought their sheep onto the plains and let them graze before the grass was properly rooted, and so laid waste the land that our goats began to starve and the grassland turned to desert.”

Karis grumbled, “That was forty years ago. Neither one of us was even born then.”

“I won’t translate that,” said Zanja.

“Well, remind her that Harald G’deon intervened, and forbade Shaftali people to graze upon the plain, and replanted the grass, and sent wagonloads of hay to feed the goats. And remind me to thank Emil and Medric for forcing me to learn so much history.”

After Zanja had reported this history, Kamole replied, “That may be what happened. But now this illness was brought to us by evil fleas, and none of the Juras brought those fleas to our land. I know this is true.”

Zanja said, “It’s true that Man‑in‑Rolling‑House brought the fleas here, inadvertently, and now he is dead.”

“So!” said Kamole.

“And we have come to cure it,” Karis said. “The healer will remain with the Juras as long as you need him–will you refuse him hospitality?”

No, Kamole did not plan to turn away a resource so valuable as J’han, despite her objections to strangers. And it would have made no difference if she had, for the fourteen Juras clans were fiercely independent, and would give J’han shelter no matter what Kamole said. Zanja wondered if Karis would ask hospitality for herself, but she did not, and if she were hoping it might be offered voluntarily, she was disappointed.

As the sun began to set, Karis, leaning on Zanja, walked slowly out of the great camp, among the goats upon the open plain. There they drove a staff into the sand for the raven to perch on, and spread their blankets in the grass. Karis lay for a while with her face in the sand. But then she turned onto her back and looked up at the sky. That broad expanse, unbounded by tree or mountain, had unnerved Zanja, for in the high mountains, with all the world below her, she had never felt so exposed. But now the sky was a glory. “We’ll watch the stars come out,” Karis said.

They watched, huddled together for warmth, Zanja with her head resting in the hollow crook of Karis’s bony shoulder. The goats closed in, and wheeled around them in a benign examination. The fearless kids, with the remains of umbilical cords still hanging from their bellies, came right up and stared them in the face. The sky’s colors slowly cooled, and stars pricked through the blue like distant lamps. Zanja told Karis of her travels. Karis said she could not remember being ill, and when her delirium had passed she wondered why her hair had been cut. Lomito had returned from his trek by then, and explained it was bad luck to have tangled hair.

Zanja said, “If they had cut my hair I would think they were making me an outcast.”

“Well, they just want to make me seem more like them. Untie the knots, will you? I don’t care if I offend them.”

Zanja worked by feel to undo the knots of yarn. “J’han remained in the sick camps, I assume. Why did he let you go to the gathering?”

“He sent me away to get some rest.”

“You were healing people?”

“I couldn’t help it,” Karis said, and added, “You’re laughing at me.”

Zanja put her fingers through Karis’s springy hair. Her own hair kept getting in the way. Karis lifted away the hair curtain and clasped it in a fist at the nape of Zanja’s neck. Zanja kissed her. Karis’s mouth opened under hers; she uttered a small sound. The goats that had lain down around them looked at them in some surprise.

There was an amazing sound, a swell of loud, sweet, deep voices. The Juras had begun singing to the stars, which filled the sky in a brilliant crowd of lights. Karis was crying hoarsely, undoing buttons ahead of Zanja’s mouth and tongue, and kept getting herself tangled in Zanja’s loose hair. The voices rose; the empty sky blazed with light; the sand vibrated with sound. Karis gasped, uttered a small shout. A newborn kid asked its dam a sleepy question. The Juras sang glory into the sky.

Later, Zanja put Karis’s clothing back on her so she wouldn’t get chilled. When she finished doing up shirt buttons, she discovered that Karis’s face was silvered with wet starlight. “What?” Zanja said gently. Karis put her arms around her, but was too weak to hold on for long. Resting on Karis’s breast, Zanja said, “I thought the cards told me you would die. I should know better than to ask them a personal question.”

Karis rubbed a sleeve across her face. The Juras were still singing, but softly. Perhaps it was a lullaby for their children and their goats. Karis said, in a rush of ragged words, “Just before I fell ill, Mabin apologized for her wrongs, and asked me to sit in the G’deon’s chair. Norina says she was sincere. But I did not accept.”

Zanja thought, I must not flinch. But she already had.

“I could not accept!” Karis’s voice was raw–not just fatigued, but fearful, agonized.

Zanja rested her forehead against Karis’s shoulder. After such sweet intimacy, to confront the fact of their increasing estrangement seemed unendurable. “Karis, if I’ve made you feel like you have to justify yourself to me …”

“Fighting the plague has been a joy to you,” said Karis. “Now the fight is over, you’ll be aggrieved again.”

Zanja wanted to contradict her, and could not do so. She said painfully, “If I could choose not to be angry or disappointed, I would make that choice with all my heart.”

“And if I could choose to make you happy–”

“My happiness is not your responsibility.”

“Oh, but your unhappiness is.”

“Dear gods, is that what you think? That I blame you for my own failure to be contented?”

Karis’s big hand had lifted to clasp Zanja’s shoulder, but now it slipped down again and she said fretfully, “I can’t hold you.”

“You don’t have to,” Zanja said. She raised her head. “For five years I’ve shaped my life by waiting, though you never said that you would ever say yes to Shaftal. So my impatience is my own fault.”

Karis’s hand lifted again, and again it fell weakly to the sand.

She said hoarsely, “The plague is over. But the land still cries out to me for healing. Do you–does everyone–think I am deaf to that? I know I must do something. But I cannot act. It’s not a choice. I have no choices. I have no choices.” Her voice was blurry with fatigue.

Because she could not say she understood, Zanja said, “You need to rest.” Then she lay beside Karis, silent.

Then Juras sang–such an astonishing song!–and the stars whirled wildly in the sky. Karis had fallen asleep. The goats slept around them, a field of goats that spread as far as could be seen. Zanja blinked–she had been dozing, and in her sleep she heard Medric warning her not to put too much importance on the plague. “Nothing changes,” he whispered in her ear. “Nothing changes.”

The cards had not been wrong. Zanja had asked if she and Karis would be separated forever–and the dreadful answer was that they would not separate at all. They were bound together on the side of the cliff, trapped there, each of them unable to choose to let the other one fall. And there they were destined to remain.

Chapter Seven

“I’m weary of looking at your glum faces,” said Cadmar one evening at the peak of the spring bloom, and he dug the whisky from his footlocker and started pouring drinks. Gilly, who had already taken his evening draught of opiates, perched like a hunched crow upon his stool, sipping from his glass and uttering grave witticisms that no one would remember in the morning. After downing three glasses, Cadmar turned garrulous and started reminiscing, though there was nothing Gilly and Clement didn’t already know about his illustrious life.

“Drink,” he urged. “Drink and be cheerful.”

Clement drank, and pretended to be cheerful.

“Those were good days,” Cadmar concluded with a sigh. Gilly, as though to contradict him, dropped his glass and, slowly at first but with increasing speed, slithered off his stool. Cadmar caught him and dragged him across the floor to the bed. “The man can’t hold his drink.” He fumbled with Gilly’s shoes. “How do these come off?”

Clement helped Cadmar put Gilly to bed, and checked that he was still breathing, for the medics had warned that combining his drugs with liquor could kill him. As she stood looking down at her misshapen, sardonic friend, her heart hurt in a way that no soldier could ever admit to. Without him, her life would certainly be unendurable.

“Are we drunk yet?” Cadmar asked.

“Drunk enough,” she said unenthusiastically.

“Well then, let’s find ourselves a trull. Like we used to do.”

“General–”

He held up a hand. “You are notdrunk enough.” He filled her glass and supervised until she had emptied it. Her eyes watered; her stomach protested; she felt more ill than drunk. But it seemed apparent that Cadmar would keep filling her glass until she either passed out like Gilly or began feigning a cheerful mood more convincingly.

As they made their way to the garrison gate, she couldn’t help but ask, “Aren’t we too old for this?” She certainly felt too old.

“Not too old. Too dignified, maybe.”

“Well then–”

“But we are soldiers, by the gods! And who else are we to lie with, eh? We’ve got no bunkmates and we outrank everybody!”

She said, “But you’ve got Gilly.” She realized only then that she was truly drunk, though not pleasantly. That Cadmar still sometimes made his way to Gilly’s bed was something she was not supposed to have noticed.

“Gilly’s getting old too.” Cadmar patted her with clumsy affection. “But you’ve got no one at all, old or young. How long has it been?”

“More than five years,” she admitted.

“Five years! No wonder you are so glum.”

The gate captain coped so calmly and expertly with the phenomenon of the general setting forth in search of a prostitute that Clement realized this could not be the first time. The captain summoned a detail of a half dozen soldiers and included herself in the impromptu escort. It was a very quiet night. After spring mud came the short summer season in which the year’s food was planted, grown and harvested, while the bulk of the business and commerce was also done. From now until autumn mud, the Shaftali would work every moment of the rapidly lengthening days. Now, the shop shutters were closed, the windows were dark, the streets echoed with the guards’ hobnailed footsteps, and Cadmar’s cheerful voice seemed very loud.

They would go to a woman who did not call herself a prostitute, and made her services available only to officers. Clement felt a certain relief: prostitutes were usually smoke addicts, and she did not enjoy their company.

“I understand the whore isn’t pregnant,” said the captain. “Not at the moment, anyway. But she makes some officer a father almost every year.”

“She sells them her children, you mean,” muttered Clement.

“She claims the officer is the baby’s father.”

“Of course she does. If she’s paid enough.”

Cadmar gave Clement a reprimanding push. The captain said with strained cheer, “This is the place. I’ll ring the bell and see if you can be accommodated.”

They had reached a modest townhouse, the only building on the street with lamps still lit. A stout, plainly dressed woman answered the door, and soon the escorting soldiers had been shooed down a narrow hall toward the kitchen. Meanwhile, the stout woman left Clement in a tasteful drawing room while she showed Cadmar up the stairs.

At least there had been no unseemly argument over who would go first. On the small room’s delicate side table, a sweating wedge of cheese and a dry loaf of bread reminded Clement that she had drunk her supper. She ate, which did not settle her rebellious stomach, and then began to be bored. She shuffled a deck of cards that lay on the table, trying to remember the solitary card games she had not played in years. But then she noticed that the backs of the cards were decorated with a variety of pornographic pictures, and she leafed through them. She had never seen such a subject portrayed both explicitly and artfully before.

Cadmar came down the stairs, looking composed and extraordinarily complacent. “Listen, Cadmar,” Clement began, planning to excuse herself from the trip upstairs.

But he clasped her hand jovially, saying, “That woman has talent! I’ve paid her for us both, so don’t pay her again.”

It was hopeless. While waiting to be summoned, Clement diverted him with the pornographic cards. She decided she would go upstairs, sit by the courtesan’s fire, and let herself be entertained for half an hour by empty‑headed conversation. Cadmar would never know his money had been wasted. The servant came to fetch her, and at the top of the stairs Clement stepped through an open door that was quietly closed behind her.

She smelled flowers, very delicate and faint, and her eye sought out the source: violets, she saw, and daffodils–homely, early‑blooming flowers tucked into crystal vases. The room was warm, lamplit, painted coral pink so that Clement felt intimately embraced though the woman who was to entertain her sat on the far side of the room beside a quiet fire, with a piece of needlework in her hand. The big bed lay demurely shadowed, though its covers were folded back to advertise the pristine whiteness of the sheets.

Clement could smell not even a hint of old sex. It was a neat trick, she thought, as though she were watching a magician at a fair. The courtesan, eyebrow raised, gazed at her with some amusement. “Lieutenant‑General, I understand you’re here against your will. The general gave me some rather strict orders, however.”

“Fortunately, he is not your general.”

“Yes, it is fortunate.” The courtesan smiled, her hands busy making stitches that only a close observer might realize were haphazard. “Do come in and sit by the fire. I will not throw myself on you, I assure you.”

Clement walked across soft carpets and sat, and the chair embraced her. The courtesan served her a hot drink, sweet and milky, gently spiced. Clement sipped and felt her stomach settle, finally. This comfortable, intimate room was not what she had expected. That she hungered for this comfort, this quiet, she also had not expected. Oh, she was weary of being who she was! “Call me Clement,” she said desperately.

“Clement, I am Alrin.”

The courtesan was not young; nor was she intimidatingly beautiful. The loose silk robe she wore outlined in folds of light and darkness a heavy thigh, a lush breast, a body as comfortable as the chair in which she now curled, setting aside her fancywork and smiling as though she had a secret. She and Clement spoke of commonplace things: the town, the weather. Clement felt as if she had entered a different world, where all was mundane and not even a prickle of violence and politics could be felt. To leave the embrace of the soft green chair and enter the embrace of slippery silk and lightly perfumed skin was not so hard to do. It happened. Alrin made it happen by waiting and hinting and smiling that secret smile. Eventually, the pristine bed was put to use.

The homely flowers of spring bloomed in every crack where a bit of earth might be shoved atop a bulb. The barren garrison’s snowdrifts were replaced by drifts of flowers that the occasional Shaftali visitor had no little cause to wonder at. The soldiers could coax a flower to bloom anywhere, and would sooner risk injury than step on even the edge of a flowerbed. Clement supposed there was something contradictory about the Sainnite love of flowers; certainly, the Shaftali found it peculiar. Clement’s mother had filled her coat pockets with bulbs on the way to becoming a refugee. Clement went to the garden every day to watch her mother’s flowers bloom.

Now it was summer, and as the last of the spring blossoms shriveled in the warmth, Clement’s sudden romance with Alrin abruptly failed. “You’ve gotten gloomy again,” commented Gilly one warm day, as the two of them were making the final plans for Cadmar’s annual tour of the garrisons.

She grunted discouragingly, but the ugly man had set his pen aside. “Are we now strangers, you and I?”

“That’s an odd remark,” she said.

“It’s you who have gotten odd, friend.”

“Well.” She sighed. “I notice that Alrin’s belly has gotten round, and now I hear that half a dozen officers are bidding against each other to be named the baby’s father.”

Gilly raised his eyebrows. “You were pretending she’s not what she is?”

“Don’t make fun of me. I’ve seen your foolishness often enough.”

“I can’t deny it. So you’ll visit her no more?”

“It was a waste of money.”

“By your gods, I’d pay for it myself! A waste of money it was not!”

Clement muttered, “So all it takes to make me happy is an hour with a trull? I can hardly be proud of that.”

That night she went late to bed, not because she was up carousing, but because with warm weather came the war, and death, and the cursed duty roster. She lay awake, of course, uncomfortable on her lumpy mattress, which wanted re‑stuffing. She had propped the windows open to the moonless night, and a little bat flew in on the trail of a moth, and flapped around the room a couple of times, practically soundless but for a dry rustle like leather in a breeze, and a squeak so shrill it was little more than a scratching in the ears. Perhaps she actually slept, for when she saw a dandelion pod of fire explode against the stars, she thought it was a dream.

She stared at it, bedazzled, mystified, too astonished to feel afraid. Surely it was a sign from the gods, perhaps a sign directed only to her, a promise that her life’s purpose soon would be revealed. The fire faded, leaving a glowing trail behind. And now she heard a sound: an animal whine that became a scream the like of which she had only ever heard on the battlefield. In a few wild steps, she stood naked at the window, watching a soldier below dance a madman’s dance as his arm and shoulder burned like fatwood.

Getting dressed took only a moment. To run down the stairs to Cadmar’s quarters took another. But Cadmar was already gone: while Clement sought enlightenment, he had already realized that the garrison was under attack, and he was ahead of her, out of the building already, where the fire falling from the sky could burn him alive. “Gilly!” she bellowed, running full tilt down the hall to pound on his door. “Wake up, damn you!” She heard the muffled murmur of his drugged voice, and left him to save himself. He was no soldier, but he knew how to keep out of harm’s way.

She ran out the door and found the burned soldier moaning, charred, scarcely conscious where he had been dragged into the shelter of the eaves. The sky exploded with fire. All across the garrison there were shouts: alarmed, astonished, and terrified. She shook the burned soldier brutally and shouted, “Was it the general who helped you? Which way did he go?”

The man said something, and perhaps he thought it was intelligible, but to Clement it meant nothing. She left him and ran down the nearest road, toward the rising shouts and the glow of fire now burning the rooftops. As she ran, she heard a captain blow his horn in the distance, signaling his disordered company to follow him into battle. Cadmar would chase that sound like a hound chases a rabbit– and just as mindlessly, she thought grimly. She ran after him, her pistols unloaded and her saber banging on her leg, with the sky exploding overhead and the garrison erupting below, and as she ran she cursed Cadmar, and cursed even louder at the beauty of the deadly explosions that filled the sky.