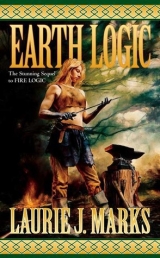

Текст книги "Earth Logic"

Автор книги: Marks Laurie

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

The raven said, “Karis is waiting for you.”

Surely the raven had not actually spoken. Certainly, it had not. Garland continued to repeat this assurance to himself, as the raven lifted its wings and flew nonchalantly down the road, to perch on another rooftop and glance back–impatiently? “I’m losing my mind,” Garland muttered. “Soon the pots will start reciting recipes to me.” He picked up his basket, which was laden with tins of tea and spices, a couple of pair of woolen stockings, a half dozen wooden spoons, a rolling pin, and a few other things, and started down the road. The raven flew ahead of him, never out of sight, looking back at Garland with unsettling intelligence, until they had reached the edge of town. Two other ravens waited on the roof of the supperhouse where he and Karis were to meet, and they greeted the third with raucous, hoarse cries. Were they now talking to each other? It almost seemed they were. Garland set his basket at his feet; he could not make himself go one step further.

A fourth raven arrived, and the others shouted their greetings. Garland turned, slowly, reluctantly, to look in the direction from which the fourth black bird had arrived. He saw a wandering man, shabby in the way that wanderers get, carrying a big, heavy pack such as peddlers carry. The man was standing still in the middle of the road, like Garland, looking at the ravens on the rooftop. His eyes were bright with tears. Garland heard the supperhouse door creak open. He heard Leeba cry, “Daddy!” She ran past Garland, shrieking joyfully, and jumped into the peddler’s arms.

Karis came out to stand at the top of the supperhouse steps, with her big hands tucked into her belt. The peddler danced in the street, turning and turning with his daughter clasped to his chest, kissing her head in rhythm with her enthusiastic outpouring of words: “I kept asking and asking the ravens where you were, but they wouldn’t tellme. And Karis is going to make me a bed out of sticks! Daddy, is Zanja dead? I don’t want her to be dead.”

“Me neither.”

“Karis cries.”

“So do I. Do you?” Eventually, the peddler set his daughter down. He and Karis looked at each other.

Karis turned abruptly away from his gaze and said, “Garland, I’ve ordered a meal already.”

Garland said, “I just came to give you these things. And to say good‑bye.”

The peddler had glanced at him in some surprise. Leeba explained, “That’s Garland. He makes jam buns.”

“And I got you a present, Leeba,” said Garland.

Karis said quietly to him, “At least come in and eat something, and let us settle our accounts.”

Garland had no choice then, for Leeba had grabbed him by the trouser leg and was dragging him insistently towards Karis, dragging her father as well by the hand. “Come on.You’re so slow.I want my present!”

The man Garland had taken for a peddler said to him, “I’m J’han.”

Garland gave a nod. “Karis’s husband.”

“Well, not exactly.”

They were in the supperhouse then, and J’han’s pack was tucked out of the way, and Leeba insisted on sitting in his lap, while continuing to demand Garland’s present. Garland dug it out of the basket: a brightly painted wooden lizard purchased from the same wood carver who had made the spoons and rolling pin. Soon Leeba’s rabbit had come out of her pocket to make the lizard’s acquaintance, and they appeared to be destined to be fast friends.

Karis, even more grim and red‑eyed than usual, sliced and passed the bread. Garland gave her an accounting, and laid on the table all the money that was left. She added more coins and pushed it back to him. “For your work these four days.”

“You’ve sheltered me and given me clothing.”

“Please, take it. It can’t be easy, to be a Sainnite in this land, without friends or family. I can always make more money.”

With nerveless fingers, Garland took the coins. He glanced at J’han, who must have heard her words but kept right on buttering his bread. Garland said, “Five years I’ve been wandering, and no one’s even guessed …”

“Earth bloods don’t guess,” said Karis.

Tearing his bread in half to share it with Leeba, J’han said, half to himself, “We know what we know.”

In the silence that followed, Garland, who had been poised to stand and flee, felt himself grow slowly heavier in his chair. A young man swathed in an apron brought roasted potatoes, onions, and pork, and a small pumpkin with a spoon in it so they could scrape the flesh out of the skin. When he was gone, Karis said, “My mother was a Juras woman and my father a Sainnite. But no one doubts that I’m Shaftali, so why should I call you something else? We are no different from each other, really.”

J’han said, easily, “In fact, anatomically the three of us are identical. Leeba, lizards don’t eat bread and butter. It makes them sick.”

Leeba said, “Medric is a Sainnite, isn’t he? Karis, when will Medric come? I want to show him my lizard.”

“Ask the ravens,” Karis said.

Leeba looked sullen. “The ravens won’t talk to me any more!”

J’han was gazing at Karis, though, with an expression that Garland could not interpret. He seemed a gentle man, and perhaps he knew how to help Karis. To have him in their household might be a great relief. And it would be easier to cook for four.

Garland cut himself a bite of the roast, which was overcooked, and ate a potato, which was bland, and restrained himself from grumbling about people who call themselves cooks. But Karis, her mouth full, said seriously, “You could have cooked this meal ten times better.”

“Roasted potatoes should have rosemary. I’ll make some tomorrow, and you’ll see.”

“I’ll build you a bed tomorrow,” she answered after a while. “I’ve got enough nails, now.”

J’han said to Leeba, “Tell me about our new house.”

Chapter Sixteen

With a half dozen nails pressed between her lips, Karis looked quite menacing, but her hands covered Garland’s so gently, he could scarcely feel the scratching of her rough palms as she used his hands like intelligent tools to bend and shape the supple twig, and then hold it in position while she tacked it in place. She had carried in the twigs through the morning’s downpour, from the brush pile she had formed while clearing the road. Now Karis had constructed three chairs out of the twigs, one child‑sized, and had nearly finished a fourth. She had yet to break or split a single twig. Leeba had made a chair, too, imitating Karis with substantial help from J’han. The stuffed rabbit now sat beside Leeba on its own chair. “Rabbit is planning,” Leeba said.

“Planning what?” asked J’han, who was methodically unloading his pack onto the kitchen table. Garland had sanded and oiled the table that morning, and now felt as if he could roll out his pastry on it without shame. When J’han had politely asked permission before putting his pack on the table, it had pleased Garland immoderately.

“Planning important things,” Leeba said.

J’han nodded gravely. “Well, tell your rabbit that great things happen through the accumulation of small acts.”

“Rabbit knowsthat.”

“Sometimes I forget how smart your rabbit is.”

Garland took note of what had emerged from J’han’s pack. It was a series of miniature chests that interlocked on top of each other. J’han had the usual traveling gear as well: rain cloak, match tin, candle lantern. But Garland, who had met plenty of travelers in his five years, had never met one who carried furniture on his back. “What are those?” he asked J’han, as Karis took control of his hands again. “They look heavy.”

“You’d be surprised how light they are. Karis made them of wood sliced thin as veneer. But the contents are awfully heavy. This one is an apothecary’s shop. This one a medicine chest. And this one a surgeon’s cabinet.”

Garland said, “I thought you were a peddler.”

“That’s because I’m trying to look like one. But–see here?” He pulled back his hair to show Garland his earlobe. Across the dimming kitchen, Garland could see nothing unusual, but J’han explained, “A scar. From the earring. I trained at Kisha University.”

The university was gone now, long since burned to the ground by Sainnites. Karis spit out her nails to say, “You’d have three earrings now, if history had been different.”

Garland knew enough to know it was a compliment. It also was the kindest thing Karis had said to anyone since Garland met her. He felt obliged to stammer out an apology for the Sainnite destruction of the university, but J’han hushed him. “We’re more interested in how to flesh out a new future on the bones of the past,” he said. “There it is,” he added, and took one last box out of his pack.

“What’s that?” Leeba leapt up. “A present?”

“Not a present for you. It’s a book for Karis, from Medric.”

With her mouth in a thin line, Karis finished tacking down the twig, and told Garland to take a rest. He went to the hearth to stir his pot and add more wood to the fire, then rather hesitantly asked J’han if he would pull the tooth that ached so it kept him awake at night.

“Of course,” said J’han. “Or maybe I could repair it.”

“Can I watch?” asked Leeba.

But Garland felt Karis’s hand on his shoulder, and turned, and she quietly said, “Hold still,” and cupped his jaw in her coarse, gentle hand. Just like that, Garland’s tooth stopped hurting.

“You’re taking my business,” J’han complained mildly.

Karis turned away from Garland. “What did Medric say?”

Garland tentatively rubbed his jaw, then surreptitiously stuck a finger into his mouth to probe his sore tooth. It gave him not a twinge.

“To read the book,” J’han said.

Karis made a sound, halfway between a snort and a sigh. “Let’s finish that chair.”

But Leeba protested, “I want to know what’s in the box! Show me!”

“It’s Karis’s present.”

“Can I look at it, Karis?”

“I don’t care.” Karis knelt again beside the chair.

Garland went back to help her, still probing his tooth with his tongue, and thinking rather dazedly that he had yet to discover one thing that Karis could not do.

Assaulted now by Leeba’s shrill impatience, J’han cut the box’s bindings, and then spelled out for Leeba the letters written on the cover. “It says, ‘Be Very Careful.’ But I haven’t been at all careful, I’m afraid.” He opened the box, and Leeba said in disgust, “It’s a box of ashes!”

“Oh, dear. Karis, I’m afraid even you can’t fix this. Bring it to her, Leeba.”

Being very careful, Leeba brought the open box to Karis, who took it from her, glanced at the bits of burned paper that filled it to the rim, and dropped it on the floor without ever taking the nails from her mouth. Leeba, apparently impervious to Karis’s ill temper, got down on her knees, crying in excitement, “Look, it’s not all ashes!” She began blowing enthusiastically into the box. The frail remains of the printed pages floated upward on her breath, then, as they landed on the floor, disintegrated into dust. Leeba’s puffing uncovered the solid remains of the book. With the bound edge still intact, and the other edges burned into a curve, it looked like a half moon. On the charred, curling edges of the leather cover, the title, stamped into the leather and once burnished with gold, was faintly visible. Once, the book had been quite large, for even in its drastically reduced state it was big enough, and must have been a heavy weight on J’han’s back.

“Can I open it?” Leeba asked, already reaching for the cover.

Karis, bending a twig, did not even glance at her. J’han said, “Be very careful.”

“I am.”

As Leeba opened the book and turned the pages, Garland glimpsed a densely printed page, and a carefully rendered etching of a pig with all the cuts of meat marked. It was reassuringly commonplace. Leeba turned the pages: more pigs, cows, sheep, oxen, horses. The fragile paper shattered as Leeba turned the pages.

Karis bent, trimmed, and began to secure the twig that finished the chair. Soon, they all could sit down, though it appeared they would have nothing to sleep on for another night, not even Leeba’s lizard, who had been promised a lizard‑sized bed.

“The other book isn’t burned at all,” said Leeba. “The baby book.”

“What?” J’han came over to look. “Well. How about that!”

Garland, his hands still holding the last twig, looked over and saw that a hole had been carved out inside the massive volume. Tucked inside it lay a book so small that, despite the big book’s burning, its own edges remained unscathed. Its red cover shone brightly, unfaded, as though it had never seen the light.

“Can I take it out?” Leeba plucked the child out of its womb. “I can’t open it! Daddy, you try.”

J’han took it from her. “Maybe its pages are pasted shut. Why would someone go through so much trouble … ?”

“Karis!” Leeba said. “Fix it!”

Karis spat out her nails into the nail bag, and set her hammer on the floor. “We’re done,” she said to Garland. “Did Medric tell you the little book was there?” she asked J’han.

“No.”

“He’s a sneaky little rat of a man,” she said.

Leeba giggled.

Karis held out her hand for the baby book.

Silence descended. Even Leeba, who was quiet only when she slept, stared at Karis, open‑mouthed, as Karis pressed the book between her palms. Her hands were so big, and the book so small, that only its red edges could be seen. The fire uttered a sudden pop, and spit embers across the stone hearth. Karis opened her palms as though they were the book’s covers, and the book opened with them: sweetly, obediently, its pages rustling like starched sheets being unfolded.

“Oh!” sighed Leeba.

The way I am with cooking,thought Garland, Karis is with the whole world.

He glanced at J’han, who sat down in one of the chairs.

Karis said in a low voice, “Earth magic had sealed this book.” She bent her head over the handwritten page, seemed to read a few words, and then, abruptly, slapped the book shut. Her face looked rather pale.

Leeba came out of her fascinated paralysis. “What is it? I want to see!”

“I think it is a letter.”

“A letter in a book?” Leeba paused, her lively mind apparently stalled for a moment by the challenge of deciding which of many questions to ask. “Who wrote it?”

“Harald G’deon.”

“Of course,” said J’han. “Who else?” He wiped his eyes on his sleeve.

“Who’s that?” asked Leeba.

“He was an important man, who created me and then abandoned me. Just like my father did, actually. I never knew him.”

Leeba crawled into her own father’s embrace. She had not let him out of her sight for a moment since his abrupt appearance the other day. Secure now, she asked, “Is the letter written to you?”

“I’m the only one who could have opened it.” Karis looked down at her closed palms. “But he must have written it before he got sick–before he sent Dinal to find me in Lalali.”

Garland had been slow to understand. Hearing the names of the last leaders of Shaftal spoken casually as part of a fragmented account of Karis’s history, he thought at first that the discussion was a joke, and then that Karis and J’han were both just a little mad.

Then he remembered the fanatics he had served dinner to last winter, and their leader, Willis, who believed in a story and a vision of a lost G’deon.

Karis had put the little book inside her vest and was packing up her tools. In the book was a letter written to her by the last G’deon of Shaftal, long before his wife Dinal set out to find Karis in Lalali and Harald G’deon lay hands on Karis and vested her with the power of Shaftal.

Karis glanced at Garland, and seemed to find the expression on his face too strange to endure. She took up one of the chairs and carried it with her into the adjoining parlor, which did not even have a fire in its fireplace yet. She returned for a candle and left again, and shut the parlor door. J’han said to Leeba, “Leave Karis alone.”

“I know.” Leeba settled herself more snugly into his shoulder. “Are you going to pull Garland’s tooth now?”

“Karis fixed it already.”

Leeba sighed with exasperation. “She’s always fixingthings!”

“She’s the Lost G’deon?” Garland said. His voice came out of his throat harsh and strange, as though he had swallowed a glass of spirits too fast.

J’han said gently, “Doesn’t she seem lost to you?”

Garland sat down. The twig chair uttered a squeak as though it were surprised.

“She doesn’t seem like a G’deon to you,” said J’han.

Leeba was neither talking nor wiggling, which meant she was about to fall asleep. She gazed at Garland curiously, though, as if she wanted to know what he thought.

Garland said, “She’s always fixing things.”

Leeba grinned at him.

Garland added, “The Sainnites thought the G’deon was a war leader. A man of fearsome power.”

J’han said, “Medric, our seer, has concluded that every G’deon has been well and truly terrified of his or her own power. I don’t guess that’s the kind of fearsome power you mean, though.”

“I never thought of it that way.” Garland swallowed, feeling the room, the world, shift around him like a house rebuilding itself into a completely different shape. “What can she do?”

“It’s hard to know, until she actually does it. I’ve seen her do some amazing things. She puts things together, basically–but she could just as easily be taking them apart. And she knows it.”

“But she doesn’t?”

“Fortunately,” J’han said, kissing his sleepy daughter’s head, “Karis is disinclined to destruction.”

It’s a strange and unpleasant sensation to know my life is almost over. For forty of my sixty years, I have been thinking as a farmer does, not just of the next crop, but five, ten growing seasons into the future, always asking myself, If I do this now, what will be the result then? But now, when I think that way, my thinking collapses. I will not be there to repair any errors I might make now. And it makes me afraid to think at all, afraid to take any action at all. Can I tell you this, a secret I try to keep even from Dinal (though, really, it is hopeless)? Can I write to you as though you were my friend? Or are you so angry with me that to tell you my secrets will only seem an insult, a presumption, like a drunk in a tavern who whispers to you exactly how he pleasures his lover?

Despite herself, Karis uttered a laugh.

Well, really, what choice have you? You can close this book and walk away, but you will eventually read it. No… I am guessing.I have no way to know you. I assume you will be like all earth bloods, but how can I be certain? Perhaps your disastrous childhood in Lalali (you see, I do know something about you) will leave you bent, lightning‑struck, irreparable. Perhaps it is a bitter, foolish, short‑sighted woman who reads these words. Perhaps I have vested the power of Shaftal in a broken container.

Here Karis did shut the book sharply, and stared into the cold fireplace, breathing hard. Faint voices murmured in the kitchen. Rain sighed, and then pounded on tightly latched shutters. The repaired roof held. Karis opened the book again.

But I do not think so. You see, I am afraid, and yet I am not. It is too late for me to save you. You will have to save yourself. But I know, or I believe, that it’s better that way. By the day you read this book, you will be healed. You will no longer rage at me for doing to you what I am going to do. And you will have found a companion, a fire blood, who in turn will find this book for you, wherever Dinal hides it, just as she would find it for me, had it been hidden for me by a G’deon of the past. Some things, I believe, will not change. And so I believe in you, as Rakel G’deon believed in me, when he threw that great weight of power into me. Like stones, it was. And then I awoke from my faint to find him dead. Though everything and everyone may seem to fail you, Shaftal will not, and you will be made strong.

So. I will write to you, to a G’deon whose name I cannot know, whose present pain and power suddenly evidenced itself to me mere days ago. I write to you on the day that the healers informed me that the strange weakness I feel from time to time is a herald of my death. I will live a half year, they say, maybe a bit longer, since we G’deons can be so tenacious. (Really, we are famous for it. But perhaps, in your time, such things will have been forgotten.) I write to you, for you and I will never speak because, in order to protect you, I must leave you in that midden heap where you were born. I write to you and I am not certain why. Because I pity you? Because my many, many guilts have grown impossible to live with any longer? No, I don’t think so. I think it’s that I love you, though you don’t even exist yet, though you are just an idea. I love you, and from your distant difficult future, I can almost feel you looking backwards to comfort me. “Harold” you say to me,“I am Shaftal! All will be well! ”And that’s the truth that rises up in me that I want to say back to you. All will be well. I am an old man facing his death, writing a letter to a stranger. I have no reason to lie to you. I tell you what I know even as I doubt it: All will be well.

Karis raised her eyes from the book and wiped her face carefully. When the tears did not stop, she lay back her head and sat quietly, simply waiting. Tears fell as though from someone else’s eyes. She kept wiping them, as though she feared that they would fall onto the book and blur the ink. In time, they stopped.

Dinal has just come in. She was away, tending to Paladin business, and I had not sent for her, because I have never had to send for her before. She said, “What are you thinking, to write in the dark? Your eyes will fall out of your head” I had not even noticed that the sun had set. She lit a lamp for me, andI saw by its light that she knew. No doubt she has already talked to the healers. I never have to tell her anything important. Always, she already knows. I say things to her anyway, because it lifts the weight.“I am dying” I said to her. “I’m writing a letter”

She said, “Well, it must be an important letter.”

And then we held onto each other for a while. The wood feeds the fire. The fire transforms the wood. That is our love. But you know this, don’t you?

Karis said out loud, “I can’t endure this!” She closed the book, stood up, and paced the empty room, which Garland had scrubbed clean. The candle, which she had stuck onto a projecting stone of the wall, fluttered with her passing. Her heavy, hobnailed boots scraped the floor. The book lay on the chair seat. She looked at it from across the room. Her eyes were red, her face stark. She said to it, as though replying to its long dead author, “Did you ever knowingly send Dinal to her death? Do you know what that’s like?” And then she stopped, as though she had heard the answer to her question and it was not the answer she expected. Her angry shoulders slumped. She returned reluctantly to her chair.

Now Dinal has gone, to tell our children. Half our life together she has spent on horseback, running my errands, while I usually remain in or near the House of Lilterwess. Half the year I am in the gardens, weeding the carrots and cutting great armloads of flowers to decorate thedining room tables.Young people coming to the House of Lilterwess for the first time to be novices in one or another order, bump into me in the hallway and don’t even excuse themselves. They are too preoccupied with hoping for a glimpse of the G’deon. There I am, in my work clothes, with my hair untrimmed and dirt under my fingernails, carrying a big basket of cabbages to the kitchen. This is why we don’t trust children’s judgment! When adults look down their noses at me, those are the people that don’t rise in their Orders. Not because I am affronted, but because they still have the judgment of children, and need to grow up before they are given more power. Alas, there are too many such people here lately, besotted with their own self‑importance, strutting about in their fur cloaks and whispering with Mabin about war. Where have they all come from?

Shaftal answers: they are the spawn of the Sainnites: not the children of their bodies, of course, but the people that are created each time the Sainnites commit one of their atrocities. Anger, pain, lust for revenge, shock and horror, that is what shapes these people. That is what shaped the Sainnites as well, in that land they escaped from. In turn they shape others to be like them, and soon our land will be a land, not of Shaftali, but of Shaftali whose desire to defeat the Sainnites has turned them into Sainnites.

You know this, my dear. Or, if you do not know it, if you yourself proved incapable of reversing the bitter shape into which the Sainnites forced you, you do not know, and all is lost. Shaftal does not speak to you. Or, if it does, you do not hear. You are reading this little book, thinking to yourself what an ass I am, what a fool, for going about that fine house covered with dirt, when I could be washed in milk and dressed in, oh,I don’t know, a silk‑embroidered topcoat. Perhaps you are wearing one yourself as you read this! Certainly, with the abilities you have, you could live a rich and comfortable life. Sainnites may well be bowing down before you as the Sainnites now want us to bow to them. Oh, what are these dark thoughts!

They are the thoughts of a man who knows he must let go and trust another to do the work that he has done so joyfully (so stubbornly, Mabin would say. So obstinately. So blindly). I admit, I am proud of my steadfastness. But you are the child of a bitter land, a land in a future I fear, and perhaps steadfastness will be an unknown thing to you. Indeed, why should you be so strong when no one has stood by you? I shudder to think what has already happened to you. I quail at the thought of what has yet to happen, what I know must happen, what I dare not prevent, though certainly I can. Oh, my dear! I am so sorry!

And so I have circled back again to the thoughts that I began with: I am afraid. I must trust, and hope, in the land. The future no longer belongs to me, but to you. And you curse me, do you not?

Karis put her head in her hands. “No,” she murmured, after a long while. “No, not any more.”

Mabin has just been visiting. Of course, Dinal told her the news on her way out to saddle her horse.(My wife is an old woman! She will ride all night, like a nineteen‑year‑old.Her vigor is the benefit of loving an earth witch, she says. But I wonder what will happen to her after I die. Will she age all at once? Will she lay down her weapons and start doting on her grandchildren, maybe learn to sew? I cannot imagine it.) Mabin had made herself look very grave, so I said to her with a heartiness as false as her sorrow, “Death is a fulfillment! A closing of the circle!” And she gave me the look I deserved, which forced me to laugh at her. “Come now” I said, having put her all out of countenance. “We have always been honest about our mutual dislike. Why are you pretending that the news of my death makes you sad?”

She replied in that arid way of hers, “I suppose I thought I might convince you to think of Shaftal’s future”

It is so typical of her, to assume that only she is capable of genuine concern about our land’s condition! To think that only she is disinterested, only she can see the dangers that beset us. I wanted to say to her that the one good thing about dying was that I need not endure her disapproval any more, but I am not entirely without diplomacy, and I held my tongue.

“Where is the heir to Shaftal?” she asked.

How could I tell her that it’s better for my heir to remain a whore in Lalali than it is for her to betwisted by the angers and power struggles of this House? (I imagine, now that the House no longer stands– yes, this far into the future I think I can see– that it will be remembered fondly. But in these last few years it has been a terrible, whispering place, full of plots and angry sideways looks. And I am not particularly sorry to know it will be destroyed.) Mabin disapproves of me. How badly will she treat you? How long would it take her to turn all her forces against you?I told her a blatant lie, glad there were no Truthkens in the room. “There is no heir.”

She looked at me, aghast. “Are you not relieved?” I asked her. “Doesn’t it give you joy to know that at last you will have no impediments to your military aspirations?”

It took some time for her to recover. (It is cruel and small‑minded of me to torture her like this, but she has earned her suffering.)At least she replied more honestly then. “An army with the power of a G’deon behind it could not be defeated. But, without a G’deon … How many Paladins are there? Seven hundred?Against how many thousand Sainnites?“

“Ten,” I said, to see her jump with shock. “Or so,” I added. “No, it will not be a pretty battle. Good luck to you. Fight well!”

“You’re doing this to spite me!” she said. “You will send all of Shaftal into ruin just to ruin one woman that you hate! What kind of man are you?”

I said then, to admonish her, “I am the G’deon of Shaftal” But she will not, shall not, cannot understand what that means. She walked out in anger. So, she is to become blatantly impolite, now that my days are numbered! She is a grasping, power‑hungry woman, but that I might forgive if she had a little imagination. Unfortunately, all that air in her blood has left no room for the fire. I am sorry to be bequeathing you such a enemy. For a long time, I fear, her power will exceed yours, and I have a horror of what she might do to you. Oh, my dear.

Now the healer is coming down the hall to admonish me for taking no supper, and as soon as he sees me, sitting here with the pen in my hand, he will bid me rest, as well. Yes, here he is, saying exactly as I predicted. I will lay down my pen for now. These healers, they are gentle enough, but in their hearts they are all despots.

Karis had been laughing, and seemed to realize it only then, as she looked up from the book as though to give Harald privacy to sleep. From the kitchen, she heard Leeba’s peevish voice and the metallic clang of a ladle, banging on a tin plate. Hesitantly, she smiled at these sounds.

Morning now. Visitors were crowding the hallway when I awoke, so the healer has set watchdogs at either end of the hall, to turn visitors away. I will gladly ignore their appeals and their anxieties. If they are so weak as to be swayed by Mabin’s panic, then they deserve to suffer the results. How irritable I have gotten! Well, it is but my sense that my energies are failing, and that these people would deplete them even more, snapping up my reassurances like a pack of hounds their meat, and then baying desperately for more. Is this how I will be remembered, as a man who shut his doors against a frightened people? Well, what does it matter how I am remembered?