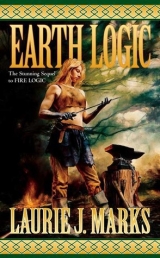

Текст книги "Earth Logic"

Автор книги: Marks Laurie

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Earth Logic

J. Laurie Marks

EARTH LOGIC

A sweeping drama of war, intrigue, magic, and love …

With Earth Logic,Laurie J. Marks continues the epic of her stunningly imagined world of Shaftal, which she first introduced in Fire Logic.

Shaftal has a ruler again, a woman with enough power to heal the war‑torn land and expel the invading Sainnites from Shaftal. Or it would have a ruler if the earth witch Karis G’deon consented to rule. Instead, she lives in obscurity with the fractious family of elemental talents who gathered around her in Fire Logic.She is waiting for some sign, but no one, least of all Karis herself, knows what it is.

Then the Sainnite garrison at Watfield is attacked by a troop of zealots claiming to speak for the Lost G’deon, and a mysterious and deadly plague attacks the land, killing both Sainnites and Shaftali. Karis must act or watch her beloved country fall into famine and chaos. And when Karis acts, the very stones of the earth sit up and take notice.

Praise for Fire Logic, Elemental Logic

“Marks has created a work that is filled with an intelligence that zings off the page…This beautifully written novel includes enough blood and adventure to satisfy the most quest‑driven readers.”

Publishers Weekly(starred review)

“Laurie Marks brings skill, passion, and wisdom to her new novel. Fire Logicis entertaining and engaging–an excellent read!”

–Kate Elliott

“Marks is an absolute master of fantasy in this book. Her characters are beautifully drawn, showing tremendous emotional depth and strength as they endure the unendurable and strive to do the right thing, and her unusual use of the elemental forces central to her characters’ lives gives the book a big boost. This is a read‑it‑straight‑through adventure!”

Booklist(starred review)

“Fire Logicis a deftly painted story of both cultures and magics in conflict. Marks avoids the black‑and‑white conflicts of generic fantasy to offer a window on a complex world of unique cultures and elemental magic.”

–Robin Hobb

For the people of Melrose, Massachusetts– especially the baristas, poets, counselors, babies, delivery people, firemen, illegal parkers, students, parents, photographers, coffee drinkers, jaywalkers, and neighbors. And also for the people who love snow, plant flowers, hang Christmas lights, and refuseto put vinyl siding on their beautiful Victorian houses. And for their dogs and cats, and for the crabby snapping turtle I rescued from the middle of the road one afternoon, and for the flocks of geese that fly by overhead.

Acknowledgments

For four or more hours a day, for more than a year, I sat writing in the front window of a downtown coffee shop, in sun and snow, warmth and chill. The people of Melrose came and went before and around me– and gradually they began waving hello, chatting, and inquiring about my progress. I am grateful to them– and I am equally grateful to the smiling young baristas who concocted my lattes, visited my table to see if I needed a refill, and stayed to ask questions about writing, language, and education. Thanks also to the friends who suffered through my incoherent first draft, the members of my writing group, the Genrettes– Delia Sherman, Rosemary Kirstein, and Didi Stewart. And, when this book had–with their help–moved beyond its early confusion, even more people read the manuscript and helped me to see how to finish it: Amy Axt Hanson, Diane Silver, Jeanne Gomol, Debbie Notkin, Deb Manning, my agent, Donald Maass, and my beloved Deb Mensinger. As my life is so filled with kind, intelligent, generous friends, it’s no surprise this book is filled with them as well.

Part 1

Raven’s Joke

One day, Raven was bored. He left his home in the cliff that can be found at the end of the world and went flying back and forth over the forest, until he noticed a woman sneaking through the trees. The woman was trying to shoot a deer to cook for her three daughters, who had big appetites.

Raven flew up ahead of the hunter until he saw the deer, which was lying in the cool shade waiting for sunset. Raven shouted, “Run away, deer, as fast as you can, for there is a hunter’s arrow aimed at your heart!” The deer jumped up and ran into the forest. Then the hunter was very angry and cried, “You are an evil bird, for because of you my daughters will go hungry!”

Raven was ashamed of himself and said, “You are right to be angry with me. So take your bow and arrow and shoot me, and take me home for your daughters’ supper.” So that is what the hunter did. She killed the Raven and cooked him in a soup.

Even though the girls ate the soup, they were still hungry, and no matter how much they ate, they stayed hungry. And the hunter, their mother, who was tired because she had been hunting all day, stayed tired no matter how much she rested. And their neighbor, who was very old and sick, never died. And the summer never turned to autumn. And the harvest never ripened. And nothing ever broke, but the things that already were broken could not be mended.

One day everyone in the world came to visit the tired hunter and her three hungry daughters. “Did Raven trick you into killing him?” they asked. The tired hunter told them exactly what had happened. Everyone became very upset with her and said, “Didn’t you know that Raven is the one who decides everything? He may be mischievous and hard‑hearted, but without him we cannot go forward with our lives. You should have thought of what you were doing. Now we will never see our children grow up, and whatever we are now, that is what we will always be, and nothing will ever change.”

They all thought and thought, and then the hunter’s youngest and hungriest daughter said, “I know where Raven’s bones are.” So they dug all Raven’s bones out of the ashes of the fire. The middle daughter took some string and glue and put all the bones together the way they were supposed to be. Then, the oldest daughter found all the Raven’s wing and tail feathers and glued them on the bones. Finally, the hunter took the arrow that had killed the Raven and smeared the bones with the blood that was still wet on the arrowhead. And then, all the people of the world began to laugh. “Hey, Raven,” they said, “that was a pretty good joke!” Raven, of course, could never resist a good laugh, so began to laugh too. “Ha! Ha!” he said. “That was a good joke!” And then he flew on his bone wings to the river to eat frogs and snails until he got fat and looked like himself again. The hunter shot a deer and her daughters were no longer hungry. The harvest ripened, the old neighbor died, and the world continued its journey as it should, from summer to winter, from life to death, and from foolishness to wisdom.

Chapter One

The woman who was the hope of Shaftal walked in solitude through a snow‑muffled woodland.

Dressed in three shirts of threadbare wool and an ancient sheepskin jerkin, she carried an ax in a sling across her back, and dragged a sledge behind her, in which to pile firewood. She might have been any woodcutter setting out between storms to replenish the woodpile.

The season of starvation had brought down another deer. It was frozen in a bed of churned‑up scarlet snow, and the torn skin now lay in stiff rags. Rib bones gleamed with frost, the belly was a hollowed cavern, and a gnawed leg bone lay at a distance. The woodcutter scarcely glanced at this gruesome mess as she strode past, breaking through the snow’s crust and sinking knee‑deep with every step. But the ravens that followed behind her uttered hoarse shouts of discovery and swooped eagerly down to the feast of carrion. They stalked up to the deer’s remains, sprang nervously up into the air, and landed again. After this silly ritual of caution they began to bicker over the best pieces.

The woodcutter, having selected a tree, unslung her ax. As the sharp blade bit into the trunk, clots of snow were shaken loose from above. The ravens paid no heed, not even when the tree fell with a spectacular crash.

The woodcutter gazed with satisfaction at the fallen trunk. Her cut had revealed the tree’s sick center, the rot that would have soon killed it. Breathing heavily, she took off her bright knit cap to cool herself, and her wild hair sprang up like the tangled branches of a thicket. “It’s cold enough to freeze snot,” she said.

The ravens, apparently easily amused, cackled loudly.

The woodcutter let her gaze wander upwards, across the treetops, toward a distant smear of smoke, nearly invisible against the heavy clouds. “Scholars! They’d die of cold before they noticed they were out of firewood.”

“Ark!” protested a raven, as another stole a tidbit right out of his mouth. They scuffled like street children; feathers flew.

“Uncivilized birds!” The woodcutter struck her ax into the stump.

The birds looked up at her hopefully as she approached the dead deer. Using a knife that had been inside her coat, she trimmed back the deer’s stiff skin and sliced off strips of meat, which she fed to the importunate ravens. The birds were not yet sated when she abruptly rose out of her squat and turned toward the northeast.

She was tall: a giant among the Midlanders. Still, she could not see over the treetops, yet she seemed to see something, and her forehead creased. A raven flew up to her shoulder. “Another storm is coming,” the raven said.

“Of course,” she replied. “But there’s something else. Something strange. And terrible.”

“In the village,” said the raven, as though he knew her mind.

“Something has come,” she said.

“No, it has always been.”

“Not always. But a long time. Longer than I’ve been alive.”

“Waiting?” croaked the raven. “Why?”

She shrugged. “Because some things wait.”

“The Sainnites came thirty‑five years ago. Is this thing theirs?”

“Yes, they brought it with them.”

After this firm declaration, raven and woman both were silent. Then, she took a deep breath and added heavily, “It is my problem now.”

“Ark!” exclaimed the raven with mocking surprise.

“Oh, shut up.”

“Coward,” he retorted.

With a sweep of the hand she flung the bird off her shoulder. He landed in the snow, squawking with laughter.

“Tell Emil what I am doing,” she told him.

She left her ax and strode off through the snow, between the crowded trees. She could see the storm coming: a looming black above, trailing a hazy scarf of snowfall. She walked toward it.

In the attic of the nearby stone cottage, Medric the seer dreamed of Raven, the god of death. “I will tell you a story, but you must write the story down,” said Raven. Medric went to his battered desk and found there a fresh candle burning and a newly trimmed pen, which he dipped into an inkwell. “What shall I title this story?” he asked.

“Call it ‘The Raven’s Joke,’” said the god, and began: “One day, Raven was bored …”

Downstairs from the seer’s book‑filled attic, a little girl was very busy. She had been induced to take a bath that morning, but now had smudges of dirt on her wool smock, and a spider web, complete with dead bug, tangled in her hair. The woman who sat on the hearth studying a book paid no attention as the girl rummaged through cupboards and closets, while conversing with the battered stuffed rabbit whose head poked out of her shirt pocket.

A man came into the parlor, looked vaguely around, and said to the woman on the hearth, “You’re letting the fire go out.”

The woman reached for a log and put it onto the coals without taking her eyes off the stained page of the ancient book. Her dark skin, hair, and eyes; her narrow, sharp features; and her long, complexly braided hair identified her as a katrimof the otherwise extinct Ashawala’i people. The book she studied was written entirely in glyphs; few could have made sense of the arcane text.

“Leeba, why have you taken my ink?” the man asked the little girl.

“I need it,” she declared.

“I need it also. What do you need it for? You have neither paper nor pen.”

“I need it for my journey. When I reach a place, I’ll ask the people there if they need anything. And if they need some ink, I’ll sell it to them. By the time I come home, I’ll have a hundred pennies.”

“A hundred pennies? Well, let’s see. How much were you going to charge for this lovely bottle of ink?”

There followed an impromptu numbers lesson. The woman on the floor rubbed her eyes, for the fireplace was smoking. Finally, she looked up from her book to push the split log further into the fireplace, and to blow on it vigorously until the flames caught. The man went out, and came back in with a sheet of paper and a pen. He said to his daughter, “Loan me some ink, I’ll make some pennies to pay you with.”

The woman studied the page, frowning–or, perhaps, scowling– with concentration. A few of the numerous slender plaits of her hair had slipped over her shoulder and looped across the page like lengths of black yarn.

The man paid for his bottle of ink with fifteen paper pennies. “Zanja,” he said.

“Don’t bother me,” the woman said.

He bent over to examine the symbol at which she glared. “My land! What are you reading?”

“Koles.”

“The poet? No wonder you’re surly. The poetry students at Kisha University used to swear he had randomly copied glyphs out of a lexicon.”

“There’s always a pattern. Even if the poet himself didn’t believe he had a reason, or didn’t know what his reason was.” Her voice trailed off into abstraction, and she abruptly reached for something that she expected to find dangling from her belt. “My glyph cards!”

“Leeba!” said J’han, horrified.

Leeba interrupted her cheerful humming. “Thirty pennies,” she demanded.

“Oh, dear,” said J’han, as Zanja uncoiled upward from her seat on the hearth.

But the little girl looked up fearlessly as Zanja plucked a pack of cards from her collected goods. “Your daughter is a thief,” said Zanja to J’han.

“I’m your daughter too,” Leeba protested.

A smile began to do battle with Zanja’s glare. “You are? How long have I had a daughter? How did it happen?”

Leeba clasped her by the knees, grinning up at her. “Thirty pennies!” she demanded.

“Extortion!”

“I’ll buy them for you,” said J’han hastily. “In gratitude. For not strangling her. Thirty pennies, Leeba?” He began counting paper pennies.

Zanja protested, “It’s too much. Look at these worn‑out old cards! They’ve been dunked in water, smeared with mud and grease, and–this is a bloodstain, I believe.”

“There must be some sweat‑stains too,” said J’han. He paid his daughter, took the cards out of Zanja’s hand, and then presented them back to her. “A humble token of my esteem and gratitude.”

Zanja was still smiling as she knelt again on the hearth, tugged the book safely out of range of the crackling flames, and began laying out glyph cards.

Leeba, who came over to watch Zanja lay out the cards, said eagerly, “It’s a story!”

“It’s a story with half its pieces missing. In fact–” She shuffled through the deck. “Did you take one of the cards? A picture of a person standing halfway in a fire?”

“No.” Leeba sat beside her on the hearth and leaned against her. “There’s a girl,” she said, pointing at the card called Silence. “Why is she so sad?”

“Maybe she has no one to play with.”

Through this method of question and answer, the sad girl’s story was revealed: how she got herself in trouble due to the lack of a playmate, and how her toy rabbit came alive after being fed a magical tea from a miniature teapot. Leeba leapt up and ran out of the room. J’han, who had been drawing again, commented, “I certainly hope that Emil’s traveling tea set is well hidden. Is this a suitable replacement for the missing card?”

He handed her a stiff piece of paper, on which he had carefully drawn the glyph called Death‑and‑Life, or the Pyre, in the lower left hand corner. Above and around the ancient symbol, he had drawn an anatomically convincing picture of a person half in, half out of a burning fire. The half that was in the fire was skeleton; the other half was a very muscular woman with what appeared to be a bush growing on her head.

Zanja gazed at it until J’han began apologetically, “It’s not very artistic.”

“It looks like Karis,” Zanja said.

“It does?” He looked at his own drawing in surprise. “I guess that makes sense. It is the G’deon’s glyph, after all. It’s natural I would draw her.”

In the kitchen, there was the distinct familiar sound of disaster, followed by the equally familiar sound of Norina losing her temper. J’han rose from his squat, saying mildly, “Hasn’t Leeba learned not to drop a kettle when that mother is in the room?” He went off to make peace in the kitchen.

Zanja said to his back, too softly for him to hear, “Karis is everything. But she’s not the G’deon.”

The parlor windows, double‑shuttered against the cold, shut out the light as well. J’han had drawn his pictures by lamplight, but he had thriftily blown out the flame as he left. Now gloom descended, and silence. By flickering firelight, Zanja studied the newly drawn glyph card in her hand. She felt no pity for the woman paralyzed in the flame.

The glyphic illustrations often gave Zanja a path to self‑knowledge, but at this moment she was reluctant to acknowledge that she might be pitiless and impatient. For four‑and‑a‑half years– Leeba’s entire life–Zanja and Karis had been lovers. Yet Zanja understood Karis less with every passing year. Like the woman in the pyre, who was neither completely consumed nor fully created, Karis remained inexplicably contented. Zanja was the one who could not endure this inaction.

She heard Emil return from his weekly trip to town. With much stamping on the door mat, he announced unnecessarily that it was snowing, and added that according to his watch, which he knew was accurate since he had just set it by the town clock, it was time for tea. Leeba loudly demanded magic tea for her rabbit. The racket brought Medric blundering sleepily down the stairs, to plaintively ask for help finding his spectacles.

“I’m afraid Leeba took them,” J’han said. He called rather desperately, “Zanja!”

“I’m coming.” She extricated both pairs of Medric’s spectacles from Leeba’s pile, and forced herself to leave the quiet parlor and step into the chaotic kitchen. There Medric, even more tousled and beleaguered than usual, stood near the stairway peering confusedly into the cluttered room, where Emil fussed over the teapot, Norina sliced bread for J’han to toast, and Leeba managed to be in everyone’s way. Zanja set a pair of spectacles onto Medric’s nose and put the other into his pocket. “Wrong!” he declared, and, having exchanged the pair in his pocket for the pair on his nose, asked, “Do you think there might be something a bit disordered about our lives?”

“We’ve got too much talent and not enough sense.”

“Really? Is that possible? Well, if you say so.” He added vaguely, “Your raven god has been telling me a story about himself. Why is that, do you suppose?”

“Whatever Raven told you,” Zanja said, “don’t believe a word of it.”

Medric managed to appear simultaneously entertained and offended. “I’m not a complete idiot. Not more than halfway, I shouldn’t think. I certainly know an untrustworthy god when I meet one!”

Medric had spoken loudly in his own defense, and everyone in the room stopped working to stare at him. Norina displayed her usual expression of unrestrained skepticism, which was only enhanced by the old scar that bisected one cheek and eyebrow. Emil gazed at Medric with amusement and respect. “That is a bizarre pronouncement.”

“Isn’t it?” An underdeveloped wraith of a man, Medric had to stretch to get his mouth near Zanja’s ear. He whispered, “Raven’s joke: nothing changes.”

She looked at him sharply, but he had already swept Leeba up in a madman’s dance dizzy enough to put all thoughts of magic tea right out of the little girl’s head.

The last time Zanja heard the Ashawala’i tale of Raven’s Joke, she had been huddled with her clan in a building much more crowded than this one, while the snow, piled higher than the roof, insulated them against the howling wind of a dreadful storm. To her people, the tale had made sense of the maddening stasis of winter. Now, perhaps Medric’s vision was admonishing her for her impatience. Or perhaps it was congratulating her for it.

“Where’s Karis?” asked Norina.

Emil looked surprised. “You don’t know? A raven told me she had gone to town, though I didn’t see her there.”

The toast was buttered, the tea poured, and the letters distributed from the capacious pockets of Emil’s greatcoat. All three men had received letters, for they each kept up a voluminous correspondence. Today, even Norina had a letter, which she viewed with doubtful surprise and seemed disinclined to open. Zanja helped Leeba with her milk and spread jam on her toast, then lay out the glyph cards again.

Once again, she studied Leeba’s sad girl, the glyph called Silence. To Zanja, silence signified thought, but to Karis it might signify inarticulateness. What has Silence to do with the Pyre, Zanja wondered? In the Pyre, death becomes life; life becomes death. But if nothing changes, the fire cannot do its work of transformation. Thus the person in the pyre is trapped between death and life, and cannot speak at all, not even to say, Help me.

In the hush, it almost seemed Zanja could hear the snowflakes floating down and settling outside the door. She was aware that Medric, across the table from her, was only pretending to read his letter. Then Norina, who had finally broken the seal of her letter, uttered a snort, Emil grunted, and J’han folded up a letter with apparent satisfaction. “The trade in smoke appears to be in a serious decline,” he announced.

“Of course it is,” said Emil. “Haven’t you healers cured almost every smoke addict in the land, now that you know how to do it?” He tapped his own letter with a fingertip. “Here’s something downright strange. Willis, from South Hill–do you recall him?”

Medric had known of Willis but had never met him, Norina had met him only once, and J’han might not remember who he was and what he had done. Zanja responded, though, as if Emil’s question had been directed to her. “Willis? Wasn’t he the one who shot me, beat me, imprisoned me, called me a traitor, and nearly had me killed? No, I had completely forgotten him.”

“I am extremely surprised to hear that,” said Emil gravely. “Listen to what my South Hill friend wrote to me: ‘We have received some word of Willis at last. He claims to have had a vision of the Lost G’deon! Apparently, he has formed a company of his own, for he believes he has been chosen to single‑handedly lead the people of Shaftal in a final battle that will eliminate every last trace of the Sainnites from the land.’”

There was a long, amazed silence. Zanja sat back in her chair and began to laugh. “Oh, Emil, write a letter to Willis and tell him exactly where the Lost G’deon is, and what she is doing.”

“Wouldn’t you rather tell him yourself?” asked Emil with a grin.

“My letter is just as peculiar,” said Norina. “Listen to this: ‘I must speak with Karis on a matter of some urgency. I beg you, in the name of Shaftal, to convince her to meet with me as soon as the weather permits travel, in a place of her choosing. Signed, Mabin, Councilor of Shaftal, General of Paladins.’”

Emil, who had just picked up his teacup, set it down again rather sharply. “I don’t believe it.”

Norina passed him the letter. He examined it closely. “Well, it appears to be Mabin’s handwriting.”

Norina said, “If Mabin thinks Karis will even be in the same region with her–”

“Mabin must think you can change her mind.”

Norina snorted. “Well, the councilor is under a misapprehension.”

Medric, to protect his unstable insight, did not drink tea and avoided both fat and sweets, so he had nothing to eat but a piece of dry toast that he had torn into bits. He now sat very quietly with his palms together and his fingertips against his mouth. He returned Zanja’s glance, and his spectacles magnified the intentness of his gaze. Even without the seer’s expectant look, all these significant letters would have seemed like portents to Zanja. At last, something was going to happen!

Then, they heard the sound of Karis stamping the snow off her boots outside the door. Leeba leaped up, shrieking with joy, making every mug and cup on the table rattle ominously. A flurry of snow followed Karis into the house. The door seemed disinclined to shut, but could not resist her. Karis let Emil help her out of her coat, and bent over so Leeba could brush the snow out of her tangled thicket of hair. The room had shrunk substantially; the furniture looked like toys; even lanky Emil seemed reduced to the size of a half‑grown child. If Karis had stood upright, her head would have dented the plaster. But it was not the mere impact of her size that made the house seem to stretch itself, gasping.

Perhaps Karis was immovable, thought Zanja, but she also was unstoppable.

Karis’s kiss tasted of snow. “Zanja, the ravens would have told you where I had gone, but you didn’t venture out the door. What was I to do? Send a poor bird down the chimney?”

Emil had pulled out a chair for Karis. The chair groaned under her weight, and groaned again as Leeba crawled into her lap. Zanja pushed over her own untasted toast and untouched cup of tea, both of which Karis dispatched before Emil could bring her the teapot and bread plate.

“There’s an illness in town,” Karis said. “And there’s going to be a lot more of it. And not just here.” She tapped a forge‑blackened fingertip on the tabletop. “Here,” she said. “Here. And here.”

J’han examined the table’s surface as though he could see the map of Shaftal that to Karis was as real and immediate as the landscape outside the door.

“And here,” Karis added worriedly, tapping a finger in the west.

Leeba peered at the tabletop, then up at Karis. “What’s wrong with the table?”

“Illness doesn’t spread like that,” J’han objected. “Not in winter, anyway. Sick people can’t travel far in the snow–so illness doesn’t travel far, either.” He frowned at the scratched, stained surface of the table.

“It was already there,” Karis said. “It was waiting.”

“Then it could be waiting in other places, too.”

“Yes.”

J’han stood up. “I’ll start packing.”

Karis nodded. She said belatedly to her daughter, “Leeba, there’s nothing wrong with the table.”

“You said the table is sick!”

“No, it’s Shaftal that’s sick.”

Leeba looked dubiously at the tabletop.

Emil, busy smearing jam on toast almost as fast as Karis could eat it, gave Zanja a thoughtful, level look. He was worrying about Shaftal– he always was. How will this illness affect the balance of power in Shaftal?He was probably wondering. Will it show us a wayto peace?

Zanja plucked a card from her deck, but the glyph her fingers chose to lay down on the table did not seem like an answer to Emil’s unspoken question. It was the Wall, usually interpreted as an insurmountable obstacle: an obdurate symbol that in a glyph pattern often meant utter negation. She could not think of what, if anything, the glyph might mean at this moment.

From the other side of the table, Medric said, “That glyph looks upside down to me.”

“Maybe you’re upside down,” Zanja said.

“Maybe you are,” Medric replied solemnly.

Zanja considered that comment. If it was intended as a criticism, it certainly was gentle enough. She said to Karis, “I’m coming with you and J’han.”

Before Karis could reply, Medric said, “Pack carefully, Zanja. I’ll go copy a few pages of Koles for you to bring with you. It’ll keep you preoccupied for months.”

“For months?” Karis asked sharply.

Medric waggled his eyebrows. “Oh, and I’ve thought of another book you had better bring along.” He headed back upstairs to his library. A notorious waster of time, he could be quite efficient when he had to be.

Norina said, “Karis, you have to look at this letter and tell me what to do with it.” She pushed it across the table.

As Zanja left the kitchen to start packing, Karis was already reading Mabin’s letter. A moment later, Zanja heard her utter a sharp shout of laughter.

Chapter Two

In the hot kitchen of the Smiling Pig Inn, Garland had finished feeding everyone and was starting the stock for tomorrow’s soup when the serving girl bustled in and informed him that a dozen people had just arrived. They had taken all the places closest to the fire, which had left the regular customers feeling put out. Garland had to make a lot of fried potatoes, and the girl nagged him to hurry up. “Give them some soup,” he told her. “You know they’ll complain even louder if I serve them scorched raw potatoes.”

“No one’s fussier about their food than you are,” the girl said, and Garland took that as a compliment. She filled bowls with bean soup and would have forgotten to sprinkle them with bacon crumbs and caramelized onions if Garland hadn’t stopped her. She complied, rolling her eyes with exasperation.

“They’re already asking about tomorrow’s breakfast,” the girl reported when she returned with the empty bowls. “They have to leave at first light, they say. And they want to carry dinner with them when they go.”

“First light? Who’s in that big a hurry at this time of year?”

“They’re skating the ice road all the way to the coast, and the old timers are telling them the ice will break up any day now.”

Garland’s heart sank. When the ice broke up, it would be spring. And what would become of him then?

“The potatoes are done,” he said. “Take those plates out of the warming oven, will you?” He served, swiftly, slices of crispy roast pork, mounds of crackling fried potatoes, and scoops of steaming pudding, all in the time it took the girl to ladle out the boiling applesauce. Five months Garland had been cooking in this kitchen, from first snow to last, and no one had yet complained that their food was cold. In fact, no one had complained at all, and many had asked for more.

“Help me with this!” the girl said impatiently. Garland glanced around to make certain there was nothing on the stove or in the oven that demanded his immediate attention, picked up a tray, and followed her out into the public room.