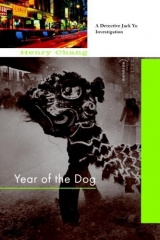

Текст книги "Year of the Dog "

Автор книги: Henry Chang

Жанры:

Прочие детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Dailo’s Money

Sai Go stood inside the front vestibule of the OTB, just beyond the cutting wind that sliced inside each time anyone went in or out.

He kept a watchful eye on the streets that crossed Chatham Square, looking for the black car coming for the dailo’s cash in his pocket.

It was 1 AM in the dead of night.

In his mind he saw palm trees and Mickey Mouse, and a pack of gray dogs wearing numbers, yelping as they dashed around an oval track.

The Gold Carriage Bakery was promoting a Holiday Special to Disney World in Orlando, and Longshot Lee had signed on for the vacation junket along with two of the da jop, kitchen help. Chat Choy had called Sai Go and asked him to come along, saying Gum Sook also had committed to the trip and had brewed up a thermos full of special herbal tea for him.

They could all bet on the dogs together.

So he agreed, and they were off the next day. Meet early, get a few baos, and tea, before getting on the bus. Bring a few newspapers. He could sleep along the way if he felt tired.

The Special included a floor show with Hong Kong singers and dancers, and a Chinese lunch buffet the entire week.

The dingy fluorescent light that spilled out of the OTB cast morbid shadows all around as the black car rolled to a smooth stop at the curb. Behind the dark windows, Lucky recognized Sai Go pacing around inside the vestibule, as he’d been instructed to do.

Lefty flashed the headlights twice, keeping the horn silent.

They watched Sai Go come out of the OTB, then Lefty killed the lights. Sai Go stepped carefully along the frozen street, looking the car over as he went. The back window powered down, and he saw the dailo’s eyes.

“Get in,” said Lucky.

There was plenty of room for Sai Go as he slid onto the cushioned backseat. He handed over an envelope, saying, “Six thousand eight hundred.”

“And I know I don’t have to count this, right?” Lucky glanced at him sideways.

“Only if you like,” Sai Go said quietly.

Lucky counted a thousand out of the envelope and slipped the bills onto the backseat next to Sai Go.

“That’s yours,” Lucky said. “For Koo Jai. The matter is closed.”

“Thank you, dailo.”

“We don’t need to speak of it again.”

“Understood.” Sai Go exited the car, saying “Thank you” again as the Riviera pulled away to make the green light. Standing by the curb in the wind, his frosty breath curling out, he pressed the extra thousand in his pocket, squeezed the wad into a roll.

The black car skirted a turn around the Square and headed uptown.

Sai Go turned and walked away from the OTB, thinking about the odds at the dog tracks, and the warm Florida sun. The group had planned an early start, and he was already feeling tired, hunched up against the gusts that grabbed at each trudging step home.

From the rearview mirror, Lucky saw Sai Go move off the Square, and turned his thoughts to Koo Jai, the wiseass, but he decided to keep to himself the knowledge of paying the little brother’s debt. For now anyway. Lucky realized the possibility that Koo Jai was the real culprit behind the rip-offs, but Skinny Chin had gone to Hong Kong and wasn’t due back until after Christmas. Kid Koo ain’t going nowhere, figured Lucky. It’d keep until Skinny got back.

Lefty urged the car back toward Mott, checking his watch, and marking the time.

Hovel and Home

The building at 98 East Broadway was a dilapidated four-story red-brick tenement near Mechanics Alley, beneath the roar-and-rumble racket of the subway trains, trucks, and mini-buses banging across the Manhattan Bridge. The building had a Chinese convenience store in a step-down basement and a cosmetics chain store six steps up the side stairs. On the sidewalk an old Chinese woman, wrapped in a shabby down coat, sat behind a folding table that dangled socks and thermal underwear, plastic sandals, ball caps, and batteries.

The back of Number 98 had a fire escape leading from the fourth floor down to a sliding metal ladder that dropped into a tiny yard closed off by an eight-foot-high fence. On the other side of the fence was a parking lot and a small shed where the broccoli vendor stashed his hundred daily cases.

The old apartments were railroad flats, long and narrow, running from the front to the back of the building, two apartments per floor. What had once been a communal bathroom in the hallway had been converted to two closet-size bathrooms, one for each apartment. Each had a tiny window that vented out back, to the parking lot.

In tenement flat number two, Koo Jai stood by the window, naked in the dim daylight, looking through the window blinds to the icy streets below. The afternoon was overcast and static with mist that promised to turn to snow.

On East Broadway and Market, four Fukienese youths stood together, one with gel-spiked hair flanked by two others in black leather jackets, their hands tucked into their pockets against the cold. Koo Jai couldn’t see their eyes behind their flashy black sunglasses, but he felt they were up to no good. The fourth youth stood to one side, a rangy, solid-looking kid who kept his right hand inside the slash pocket of his black trench coat. He was slowly rocking from side to side, in a tai chi kind of way, his eyes peering over the edge of sunglasses, sucking in every movement in the intersection.

Fucking Fuks, thought Koo Jai. The cold of the front room felt good against his overheated skin. He remembered why he’d left the thick heat of the back room, and reached down beneath the window. He pulled up a short piece of baseboard, extracted a plastic-wrapped bundle, then slipped the board back in place.

When he peered through the blinds again, the four Fuks were gone and he wondered which of the Chinatown shopping malls they were going to hang out in.

Up to no fuckin’ good, he knew.

For a moment, he scanned the small dark room. There was the bulk of the faded black leather couch, a convertible number that had to be ten years old, one of the surviving pieces of furniture from when the apartment had been the Stars’ clubhouse, where the gang partied and brought their girlfriends for sex. This was when their brotherhood controlled these streets, before their leader Tiki, and three senior brothers, mysteriously disappeared, before the Ghosts rolled in with a hundred men and took over.

There was a cheap folding table in one corner and an array of mismatched shelf units and clothes cabinets stretching the length of the long wall leading to the back bedroom. Three metal chairs were folded, leaning against the table, in case he had visitors.

For a long time now, except for Shorty coming by occasionally to smoke a joint and down a beer, he never had visitors, and the place had become his apartment, drug den, love nest, whatever. The Jung brothers, Old Jung and Young Jung, were too lazy to climb even the one flight of stairs, and since he didn’t have a television set, they were even less inclined to drop by and hang out. Just as well, he thought, no interruptions when he brought his girls up, and less chance of any of the gang stumbling upon his stash of the loot they divvied up. He used the spot behind the baseboard at the window. Another spot was under the floorboards, beneath one of the full-length wall mirrors he’d got from Job Lot, the other one mounted in the back room, strategically placed so that he could see himself with the parade of women he brought to his bed.

He unwrapped the plastic bundle and admired the dozen watches inside. Six Rados, four Cartiers, and two Rolexes. Twenty-five gees worth of fine timepieces and he’d taken the best for himself. Shorty’d gotten a Rolex and a half dozen Movados, as had each of the Jung brothers. He removed one of the Rados, a gold woman’s piece that had a modern metallic bracelet and a square black face with diamond baguettes arranged on all four sides.

He held one of the Rolexes, ran his thumb along the watchband, across the face, caressing, feeling its mechanical splendor. He heard again the words of the dailo still ringing in his ears: If there’s another rip-off, it’s gonna be on you.

Warnings from the dailo, whom he never saw except when he came to collect cash or to complain, this end of East Broadway being too far from the lucrative streets around Mott and Bayard, Canal and Pell, for social visits, were not too impressive. The next job’s gonna fall on me? Yeah, right. Fuck that. The next job’s gonna be by me, more likely. Imagine that shit, he groused mentally, drove here from Mott Street? To chew my ass?

Fuck that, fuck that, fuck that, kept banging on his ear.

Taking a deep breath, he calmed himself.

He kept the Rado, but bundled away the rest of the watches under the floorboards beneath the Job Lot wall mirror. When he eyed his reflection, he liked what he saw and paused in the shadows to admire his own nakedness. Almost five-foot ten, he had a body like Bruce Lee, but on steroids, and a face that could have starred in movies in Hong Kong. Handsome in a cool way. A lover and a fighter. It was because of all the women in his life, he smirked into the mirror. What facial hair he had amounted to a faint mustache and goatee, which he trimmed regularly because he knew the ladies liked it. And the ladies: Mimi at the New Wave Salon, who permed his hair, and shaped it according to pictures in Hong Kong movie-star magazines. Joanna, his dentist, who’d given him a winning smile. Angela, the seamstress who fixed his jackets, and who’d made it clear she wanted to get into his pants. Dana, the masseuse, who pampered his muscles, including the long one that hung loose beneath his stomach. Kitty, at the bank, who gave him the crisp new bills he liked. On and on. Women were taken in by his good looks, his dynamic energy, and his quick tongue. Some of the women would later appreciate his quick tongue in more earthy ways.

He heard the dailo ’s voice again and shook his head, remembering the Jung Wah Warehouse job. That job was mostly the Jung brothers, who had hot-wired the truck inside the warehouse after Shorty had wriggled inside and let them in. They drove off with the entire load, with Shorty locking up the warehouse neatly, and Koo Jai covering shotgun on the rip-off. But abalone and bird’s-nests? They’d unloaded the stuff to the Jung brothers’ cousins who operated a market in Boston Chinatown, but they hadn’t seen any money yet. What the fuck? It would be weeks, maybe months. He’d thought it was a stupid heist but went along to give the Jung brothers face.

He went to the table and took a gulp from the bottle of mouthwash there, gargled, and ejected the green spew into a plastic garbage pail. Thinking it might be better to cool his plan to rob the Fuk’s mahjong club, he sucked out the rinse where it leached into his gums and spat again. The old floorboards still creaked under the dingy linoleum, even after he’d covered it with cheap area rugs from Kmart.

From the back room he could hear the rustling of the comforter, then a soft murmur, like a sigh. He went toward the musty heat, the Rado in one hand, his cock in the other as he thought about Tina, lying exhausted but insatiable in his bed.

She was the night manager at KK’s Karaoke, a basement spot on Allen Street. Koo Jai had done her several times and he knew she hoped to be his girlfriend, even thought she could get rid of the others.

He slipped under the comforter, in the darkness behind the drawn shades, feeling for her. He put the Rado on her wrist, and she moaned, thinking, Not the handcuffs again.

Koo Jai nuzzled the nape of her neck, his cold hard body sucking the heat from the comforter and the hot contours of her backside.

“Ooooh,” she moaned, so cool. She turned and nestled all of her soft and wet parts against him. Admiring the Rado, she slipped her head down to his stomach and wrapped her hot lips around the thick popsicle there.

He watched the tangle of hair pumping back and forth on his lun cock, and wondered how long before he could rob the mahjong club.

Pay off

Bo crossed the Bowery toward the long blocks of jewelry stores that ran down the northside stretch of Canal Street. Fifty shops named Treasure Diamonds, Lucky Star Jewelry, Royal Princess, Golden Jade, Canal National Gems, with the lights blazing from their windows brightening the concrete gray gloom drifting west toward the Holland Tunnel.

She always made her payments on the first Sunday morning of every month, as soon as the stores opened, so she wouldn’t be delayed by other customers.

Almost to Mulberry Street, she paused at the bulletproof glass door of Foo Ling Jewelry and Jade, and waited to be buzzed in.

The Foo Ling’s street windows displayed a dazzling array of diamond rings, bracelets, necklaces, and custom setups mounted with rubies or emeralds, all gleaming under the brilliant halogen lights. There were trays of gold medallions, racks of thick glittering chains, and a section of rich green jade pieces, some carved and beaded into pendants.

She stepped into the dry heat spreading from the lights, went past the display counters along the walls.

The bald-headed old Chinese man sat alone in the back end of the store, his fat bottom propped against a wooden stool. He twisted his frown into a half-sneer, half-smile, removing his finger from the remote door button as he watch Bo approach. Her eyes avoided his.

Hom Sook was how she was first introduced to him, her contact for remitting the monthly payments, and that was how she addressed him regularly now, always reminded how the spoken Chinese words sounded like hom sup, horny, old lech.

The name fit him well, she thought.

Hom Sook was sixtyish, obese, and reeked of the pork dumplings and curry chicken that he loved so much. He had a big head with reptilian features: thin lips, hooded eyes, and a flat nose.

Bo pictured this snakehead each time she prepared her payment envelope.

This time he’d worn the cheap gray rayon shirt with a design of tigers and eagles dueling in the background. He smirked, leering at her, when she handed him the envelope of money.

Bo had always kept the exchange brief, waiting just long enough to see him make the notation. She didn’t want to engage him in conversation, knowing where it would lead.

“Leng nui,” he called her, pretty woman. “ You look tired,” he said in a slithery voice. “How are things with you?”

“Fine,” Bo answered evenly. “Thank you.”

“Have you reconsidered our offer?” he asked, the snake tongue licking his lips.

They had wanted her to whore for them, had promised her a choice of regulars, clean-cut family men who were easy to please. Easy work, they’d said. Money for laying on your back.

“No, thank you,” Bo repeated as he counted out the money, then made a notation in his black book. Seeing this, Bo turned for the door. The old lech swallowed back his lust, his eyes keening to the soft sway of her backside as he made her pause before buzzing her out.

“Leng nui,” he chortled, “see you next month.”

Outside the Foo Ling, Bo took a deep breath, welcoming the cold breeze that swept down Canal. She felt better as she walked, thinking of a small sunny village in the south of China, picturing her daughter and her mother there, half a world and three lifetimes away.

Time and Space

Bo sat in the quiet solitude of her little rented room above Market Street, the silence broken only by the clicking of her bamboo needles, seated at the foot edge of the single bed, her voice a whisper chanting Buddhist nom mor nom mor prayers. She continued knitting this version of her rosary, a black scarf with the Chinese words for struggle, jung jot, stitched across the top in white relief.

In the black yarn were all the colors of bad luck.

In the white yarn, absent color, the insidious tone of death.

She was playing off the bad luck.

Several inches below the Chinese characters was a repeating pattern of horizontal S’s, or white snakes. Two rows of them totaling twenty-five, now twenty-six with the one she was stitching in place.

Twenty-six snakes now. Twenty-six payments to the snakeheads.

She paused, and took a breath, let her eyes rove over the bowl of leftover jik sik, instant ramen, on a tray, over the top of the used dresser, to the grainy photograph of three women:

herself, and Mother, and small daughter in tow.

Only the child was smiling.

The little girl’s mother and grandmother wore uncertainty on their faces, had small lights of hope and resignation in their eyes.

Abruptly, Bo wrenched her attention back to the clicking needles, clicking faster now, left to right, an impatient rhythm.

She hadn’t seen them in more than a year, but they spoke every week, using the discount prepaid telephone calling cards that Sai Go had gotten for her.

Nom mor nom mor nom or may tor fut.

She focused on the needles working the yarn: slip, stitch, purl, her fingers, hands, wrists in active articulation. The same energy came from her hands when she’d cut Sai Go’s hair, massaged his shoulders.

The black acrylic scarf was almost two feet long, knitted in monthly installments of white snakes.

She prayed for strength to finish it, knowing it would take years before she’d be able to pay off the snakeheads.

Nom mor nom mor no more slip stitch, loop through, the ball of yarn twisting in the little plastic basket. Drop the white yarn, wrap the black, complete stitch.

In the back of her mind she remembered the myriad of forgotten jobs, and then the New Canton, and measured the price of freedom.

Secret Society

Gee Sin rolled down the middle window of the van just a crack, then leaned back and sipped his steaming nai cha as he observed the area around the foot of the Manhattan Bridge.

The generic gray minivan with dark-tinted windows was parked off Division Street, providing him with cover against wind or rain, with a good view of East Broadway where Forsyth Street reached up to Chrystie Park.

Gee Sin could see the rows of businesses beneath the high bridge girders: several storefront employment agencies, Chinese vendors with outdoor ATM machines, a MoneyGram shop, and a Western Union at either end of the street. On the opposite block was a hole-in-the-wall store that sold cell phones and prepaid telephone cards flanked by a fruit stand and a stall that sold socks and thermal underwear, toothbrushes and soap, necessities for newly arrived Chinese who were about to travel yet again.

Things had been set up just the way they’d planned, Gee Sin thought. Made it convenient to find work, get cash, and remit payments. Cell phones and prepaid cards to call home regularly, and be reminded about their debts.

The steam from the cup swirled toward the sliver of open window, as he felt a quick sweep of icy wind across his bald pate. The intersection was noisy and crowded this early afternoon. The bundled people shuddered under the thunder of the subway trains overhead. The only dialect he heard was Fukienese.

Gee Sin was pleased to see the streets in this area were wider, able to accommodate sweeping turns, and the stretch of streets along Chrystie Park allowed a dozen buses to park there.

There was a Mobil gas station at the corner of Allen. He’d arranged a cash-only gas-up deal with the franchise owner for the overnight buses that parked along Pike Street. His scheme for the Hung Huen was about to bear fruit. The triad, washing money, had arranged for the financing of a fleet of coach buses, two dozen to start. Since many of the riders would be Fukienese, the Fuk Chow gang would run the daily operations.

Gee Sin, or Paper Fan, as the triad members respectfully addressed him, had orchestrated every step. He had seen how important the American expansion of the Chinese restaurant industry was. As more and more Chinese restaurants, take-out shops, and dim sum teahouses flourished in far-flung American cities, the demand for cheap Chinese-speaking labor also grew. Entrepreneurs had even demanded that certain tong-connected construction crews be transported to the locale of the new restaurant, to be housed and fed there as they built– and inflated—the costs of the business.

The Fukienese, the latest wave to fill the demand for coolie workers, were sent to restaurants and malls from Richmond to Rochester, as far west as Ohio, and north to Montreal.

Twelve dollars one-way to Boston or Philadelphia would drive any competition out.

The idea that they needed a transportation system to shuttle these workers back and forth from New York’s Chinatown, the hub, made Gee Sin realize that the unregulated tour-bus business was also a natural for moving contraband along the interstates.

A patrol car cruised by.

He adjusted the cup in his hand, placed it into the slide-out cup holder between the front seats. From his pocket he fished out a bogus driver’s license the triad had created for him. The name they’d used was Bok Ji Fan, another version of White Paper Fan. He studied the photograph with a sad knowing smile.The weight of fifty years sagged around his eyes, the brows bushy and flecked with gray. He stared out of deep-set, sunken eyes within a haunted, pale face. He reminded himself that there was much to do, and his time in America was short. He was not one who was keen on travel; the month away from Hong Kong was long enough already.

As White Paper Fan, he’d gotten accustomed to the creature comforts of Hong Kong that accorded his rank and seniority in the Red Circle.

New York was nothing but cold and gray grit.

Gee Sin thought about the triad’s Grass Sandal rank liaison officer who would drive them back to the rented condo apartment outside Chinatown. Scanning the street, he saw a bus discharge its passengers and head toward the park, exhaust pouring from its tailpipe. From a side street, a line of black funeral cars swept past him. He was glad to see the bad luck spirits fade into the avenue.

He checked his watch again, confident Grass Sandal would arrive soon. The street was productive, which was all he’d wanted to see. He pocketed the fake license, then picked up the cup, sipped the tea carefully, and watched traffic as he shut the window with his free hand.