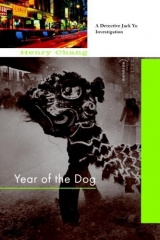

Текст книги "Year of the Dog "

Автор книги: Henry Chang

Жанры:

Прочие детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

EDP Avenue B

The trendy sushi spot was still jamming at three in the morning, full of weekend club crawlers slinking out of dance palaces like Webster Hall and Limelight, the party crowd needing to tone down what remained of the Ecstasy rush with sake and raw fish.

U2 jams kicking off the DJ jukebox.

Jack was paying for his Nabeyaki Special, a soup-and-sushi combo, when he heard a commotion outside, on the street that had been deserted on his way in.

The patrons turned their heads.

The restaurant’s manager, a young Asian Pacific dude, who tried to look yakuza but who struck Jack as more NYU Business Management School, pushed his way out the door to check out the disturbance.

Pocketing his change, Jack went toward the door.

When he stepped out onto the street he saw a short white man by the curb, in a fatigue army coat, howling up at the streetlamps beneath the cold black night. His hot breath was a rush of steam in the frozen air. He kept his hands in the coat pockets.

EDP, Jack recognized, emotionally disturbed person.

The restaurant manager, deciding how to approach him, kept at a distance.

“Excuse me, man, excuse me,” the NYU yakuza pleaded.

The ED man looked to be in his twenties, homeless, snot dripping off his nose. Looked like a bugged-eyed Charlie Manson.

He continued yelling.

Jack was wondering if any of the neighbors had called 911 yet when the man took a step toward the sushi manager.

You had to be careful with EDPs, remembered Jack; there was no telling how they’d react.

State institutions had dumped thousands of them, and many of these walking timebombs had found their way to the city, which was unprepared to deal with them.

Jack flashed his gold badge, said authoritatively, “ Hey, pal, how’s about we get you into a warm shelter? Get you a hot bowl of soup? A bed?”

He imagined he heard sirens in the distance.

The disturbed man turned toward Jack, and smiled, slowly bringing his hands up to his face. He pulled back the outside corners of his eyes, making slanted chinky eyes. Then he laughed, a big howl.

“Ya Jap muddafukker!” he screamed at Jack. “You ain’t no cop! Ya sneaky cocksucker!” He spat at the Asian manager, who stepped away from Jack.

Okaay, realized Jack, disturbed, but not so disturbed that he couldn’t dredge up the racism in his soul. The words and curses drove the humanity and compassion out of Jack’s heart. He saw the man now as just another deranged skell, a danger to himself, if not others.

The skell dropped down into a kind of Kung Fu stance, making catlike Bruce Lee sounds.

Be cool, Jack thought, taking a step back. The skell’s mind might be screwed up, but that didn’t mean there was anything wrong with his body.

Suddenly the skell launched himself at Jack.

Instinctively, Jack twisted his hip and leaned back as the wild man’s foot whipped up, missing Jack but punting his sushi takeout into the street. The Manson clone’s right hand came out of the coat with something metallic, swinging down toward Jack in a wide arc.

Jack threw up a bow arm that blocked the attack, and stepped into him, hooking his foot, and throwing him off balance. Jack rocketed a stiff palm into his chest and the skell fell backward, into a dive. After he hit the sidewalk, Jack put a knee in his back and slammed his wrist, sending a box cutter skittering along the sidewalk. The fight went out of him when the cuffs went on. Crazy, but not stupid.

Jack caught his breath while the sushi manager profusely thanked him, the ying hung hero of the moment. Splattered along the gutter were the udon noodles and the hamachi.

Flashing lights from the patrol car less than a half-mile away.

Down the avenue, EMS rolling in.

They’d work out the chain of custody, and the EDP would wind up in Bellevue for psych observation. Homeless outreach services would follow. Eventually, he’d be put back on medication and released, another timebomb, back into the population.

There would be future victims.

By the time Jack got it all straightened out with the uniforms he’d lost his appetite, and made his way back to the station-house for the end of the overnight.

White Devil Medicine

Sai Go fingered the switch, and stood in the dim yellow light. He noticed it was past 4 AM as he removed his wristwatch and laid it on the counter of the bathroom sink. When he looked in the mirror, he saw a haggard beat-up old man. He was only fifty-nine. Dead eyes that were sinking into the emaciated face. The gray-white crewcut hairs sprouting out, in need of a trim. The stubble spreading from his chin.

The little plastic bottles were in a line up behind the sliding mirror glass of the medicine cabinet. Although he was proud that he could usually read aloud in his broken English the colorful names assigned to the horses on the racing form, the words on the pill bottles were unfathomable.

Taxol.

They’d found a tumor in his lung. Nodule. Adenocarcinoma.

He was finding it hard to stay focused.

Vinorelbin.

One pill twice a day. One pill every two days.

He forgot which was which. The pills had him in a daze.

The red ones with the white stripe, every third day.

The blue ones, one a day?

The yellow tablets, the purple capsules . . .

Leukocidin.

Words that were meaningless to him, like small black bugs flitting across the square of prescription notepaper from the clinic. New sounds that rattled in his ears, alien noises.

Gum Sook, the herbalist, told him to stop smoking, and to brew up some tea of Job’s tears and brown sugar. No lizard or bladder or powder of horn or dried bull penis.

Chemotherapy.

Radiation.

More dancing bugs. He’d lose his hair and be sick a lot.

Chat Choy, the head chef at Tang’s Dynasty, advised him to boil three cloves of garlic, eat them with soy sauce. Longshot Lee, senior waiter at the Garden Palace, said with quiet confidence, “Fry three cloves of garlic in olive oil, add black pepper, ginger, and salt with shiitake mushrooms. Twice a day. Two months.”

Fifty-nine’s too young to die nowadays.

Four months left was not enough time.

Forget all this, he concluded in his exhaustion. We all die sooner or later.

I’m not taking any more gwailo pills. It was more painful trying to stay alive than to accept dying. His thoughts began to scatter far and wide, somewhere between being high and falling down dizzy. It was all unraveling now. He felt it in his cancer blood, paying for his sins, his life in free fall, spiraling down helpless and hopeless.

He coughed quietly and swallowed, already tasting the blood in his throat. Flicking off the light, he let his eyes adjust and left the bathroom.

The living room was dark, but he turned on the television set and let its light fill the room. He thumbed down the volume and rewound the videotape player to the second race at Happy Valley. On the shelves next to the cable box he’d set up his own little wire room operation, where he charged up his cell phones, kept his pads of soluble paper, and reviewed the odds at different overseas race tracks.

In the glare of electronic light the twenty-year-old living-room set exposed a beat-down convertible sofa bed, matching wood-veneer end tables, and a desk that served as a dining table.

He sat down on the sofa and started the videotape. A sunny day in Hong Kong, but he could see it was a sloppy track. They’d probably had rain in the morning.

The riders, with their colorful silk outfits calmed their mounts as they loaded into the gates. He followed the horses: Gung Ho Warrior, Buddha’s Baby, Fool Manchu, Happy Dragon, Sword of Doom, Baby Bok Choy, Noble Emperor, Ming Sing, Chu Chu Chang. Double Happiness, and Secret Asian Man, and Geisha’s Gold. A crowded field of twelve.

Suddenly, they were off, breaking from the gates. With the volume off, Sai Go was calling the race in his head, seeing the fix with wicked clarity.

At the break, it’s Geisha’s Gold along the rail, with Noble Emperor challenging for the lead, followed by Buddha’s Baby. Fool Manchu and Baby Bok Choy a length back for third. A gap of two, it’s Double Happiness, Ming Sing outside him, and Chu Chu Chang, settling in toward the rail, with Secret Asian Man and Happy Dragon chasing them. Gung Ho Warrior drops back, with Sword of Doom bringing up the rear as they pound into the first turn.

It’s Geisha’s Gold and Noble Emperor chased by Fool Manchu a length back, then a close-packed crowd of Buddha’s Baby and Chu Chu Chang in front of Baby Bok Choy, Ming Sing, and Secret Asian Man. Happy Dragon boxed to the rail by Gung Ho Warrior and Double Happiness. In last, Sword of Doom is stalking them all.

Down the backstretch it’s still Geisha’s Gold and Noble Emperor. Behind them the others are scrambling for position, dropping in, and saving ground, barreling out or breaking sharply, all driving to catch the leader. The pace quickens; Ming Sing is in ninth position. A half mile to go.

Secret Asian Man dances around the outside and takes the lead. Ming Sing is boxed in along the rail in eighth place. The field is bumping and pushing the leaders.

They come to the clubhouse turn.

It’s still Secret Asian Man, with Buddha’s Baby, and Chu Chu Chang ready to pounce. Ming Sing is in seventh.

They’re three-wide off the turn. Double Happiness, Chu Chu Chang, and Buddha’s Baby. Ming Sing is sixth, the rest of the field digging for the leaders.

At the top of the stretch, the jockeys are waving their whips.

The leaders spread apart a gap. Ming Sing dodges out and follows Double Happiness down the middle of the track. Sword of Doom, fighting through horses, chases them. Buddha’s Baby loses ground, and Chu Chu Chang blocks off the rest of the field.

A mad dash the last three lengths and at the wire it’s Ming Sing by a neck, then Double Happiness, and Sword of Doom. Buddha’s Baby finishes fourth.

Sai Go pumped his fist and cheered quietly. The race, which took merely a minute to run, had been a thing of beauty. He waited for the posting of the payout, thinking that his exotic bets, via his man at Happy Valley, were going to bring in more than ten grand. He had taken Lucky’s pick, Ming Sing, and boxed the bet with other longshots into double and treble wagers. The exotic bets available in Hong Kong made the same type of action in the states seem like standard play; pay-outs in the Fragrant Harbor were astronomically higher.

He downed a shot of Chivas and sat on the sofa as he waited.

The numbers came up on the screen.

The dailo Lucky had won more than six thousand, but Sai Go’s own exotic bets had won him over eleven thousand. Minus the dailo’s money, his take was over five thousand, all from working a hot fix.

The money would be wired into his U.S. Asia bank account the next day, minus his Happy Valley cohort’s commission and the transaction fee.

Sai Go rubbed his eyes and turned off the set, plunging the room into blackness. What to do? he wondered. How to enjoy the jackpot? when the irony of it all came back upon him.

What was he thinking? With four months to live, he was getting excited about taking five thousand out of Happy Valley? Should have made a list, he thought, of all the Chinaman things to do before cashing in.

Go to Bangkok, drink, and fuck himself to death.

Go see all the places he’d never been.

Go home to Hong Kong and China to say good-bye to the few elderly relatives who were still on speaking terms with him.

Now, closer to the end of the line, he wasn’t sure he wanted to take his death on the road. He considered making his last stand in Chinatown, hunkered down in his rent-controlled one-bedroom walk-up.

He had about twenty-eight thousand in the bank, and a fifty-thousand-dollar life insurance policy from Nationwide that still listed his ex-wife as beneficiary. That was it. No wife, no kids, no family. Parents long since passed. His sister and cousins, all estranged. World without end, amen.

He knew he needed to take his money off the street, call in all debts. He could explain, if necessary, that he was starting a bigger operation, and required a larger financial investment. Once he recouped everything, he told himself, he’d still have time left to do whatever it was that one does at the end of one’s life.

He thought about getting a haircut, a massage, a Chinese newspaper, but quickly fell asleep on the sofa, in the darkness unsure of where the rest of his life would lead after that.

Roll By

In the rush-hour morning, Jack caught the M103 bus running, almost at St. Mark’s. The city bus brought him quickly down to Chinatown. He hopped off near Bayard and went west to Mott Street, past the old tenement where he’d grown up, where Pa had finally died.

A crowd of old folks had gathered, blocking the sidewalk outside Sam Kee Restaurant. Jack crossed the street, away from the dingy storefronts that had seen the better days of his youth.

Billy’s tofu factory was down the block. Billy Bow, the only son of an only son, was Jack’s oldest neighborhood friend. He had been Jack’s extra eyes and ears on the street, and he’d provided Jack with insights and observations into the arcane workings of the old community.

The Tofu King was the work of three generations of a longtime Chinatown family, the Bows. It was once the biggest distributor of tofu products in Chinatown, but was clearly no longer the king. Competition had grown steadily as new immigrants from China arrived, and the Tofu King now resorted to promotional gimmicks to hang on to its customers. Every Tuesday was Tofu Tuesday, half-price for senior citizens, and after 6 PM daily, rice cakes and dao jeong soybean milk were three for a dollar.

Billy’s grandfather had started it all by growing his own bean sprouts, then perfected the process of cooking soybeans and passed it on to his son, Billy’s dad, who then hooked up with soybean farmers in Indiana, and expanded the shop. Finally, Billy, conscripted into the family business, targeted their tofu products toward a more diverse health-oriented marketplace, and expanded the shop into the Tofu King. Now the business struggled, not only to maintain its place against the new competition, but also staggering under myriad business costs that kept rising.

Jack remembered the three rudderless years he’d worked in the Tofu King, in the suffocating backroom, cooking and slopping beans into foo jook tofu skins, and tofu fa custard. That was long after his pal Wing Lee died, but before Jack had finally graduated from City College.

When he peered through the steamy storefront window, he could see Billy near the back, animated, making faces, and gesturing with his hands.

Jack stepped into the humid shop and listened as Billy ranted on about the latest atrocities. “The health department, wealth department is what they should call it, comes down with a new regulation every fuckin’ month. Just so they can shake down more money from Chinamen.”

Preaching to the kitchen help, thought Jack.

“Ew ke ma ga hei, motherfucker,” Billy cursed in his best Toishanese, the original tongue of the first immigrants to Chinatown. “Thousands of dollars in fines.”

Jack picked up what he needed, went toward Billy who continued to vent in the general direction of the slop boys in the back. They frowned and nodded their heads at everything he said.

Feigning surprise, Billy turned to Jack and laughed, “Oh shit, it’s Hawaii Five-0! Green cards out, everybody! Book ’em, Jack-O.”

Jack was happy to see Billy grinning, a momentary departure from the edgy-depressive that Billy normally was.

“Wassup, man? You look like you got some man tan there.” Billy took a breath, shook his head sadly as Jack plopped onto the counter the three plastic containers of bok tong go he’d taken from the refrigerator case.

“What’s up with the crowd outside Sam Kee’s?” Jack asked.

Billy chortled. “They’re waiting for the free for ngaap duck. The inspectors said it’s now illegal to hang ducks and chickens in the window, without temperature controls. Gave old man Kee a two-hundred-dollar fine, and a citation.”

Jack was shaking his head, looking for So what?

“So the old man catches a fit, threatens to throw the ducks into the street. All the old folks are hoping to catch a freebie.”

“It’s not going to happen,” Jack grimaced.

“I don’t think so, either.”

“All he’d be doing is inviting a Sanitation rap.”

“Jack, yo, ducks and chickens been hanging in Chinatown windows a hundred years. All of a sudden it’s a health issue?”

“Hundred Year’s Duck. Isn’t that the house special at Wally’s?”

“It’s all bullshit,” Billy continued, “When was the last time we had an epidemic down here? Eighteen-ninety-three or something?”

Through the frosted street window Jack saw the green car with the sanitation sergeant seated inside, idling at the corner of Bayard.

“The city’s just trying to pump bucks by pickpocketing the Chinamen, brother. Kee junior called it the Fuck the Duck Law. The Choke the Chicken Law.”

Jack chuckled, knowing that the more things changed in Chinatown, the more they remained the same. Been going on a hundred years. Old Man Kee had probably been too slow with the payoff, or the department had sent an overzealous, perhaps racist inspector looking to advance. The Chinatown lawyers found ways to work around municipal regulations all the time. Administrations changed. This, too, would pass.

“Everybody’s talking,” Billy said quietly, “about the Ping woman. The Fukienese one who got killed?”

Jack nodded, the cause of the demonstration at One Police Plaza.

“Three hoodie-wearing punkass, hip-hop motherfucker wannabe thug gangsters.” Billy’s eyes steeled over. “And I lost half the backroom boys yesterday ’cause they went to the protest at police headquarters.”

“It ain’t easy,” Jack said.

“Fuckin’ A that. The Fukienese Association wants the punks to hang. They hired white lawyers even. Sorta like a legal lynching.”

Jack checked his watch, thinking how long-winded Billy could get.

“But crime never takes a holiday, huh,” Billy joked. “So what else you need, kid? Some fun or some skin ?” Both were references to tofu products, but sounded perverted with drug and sexual innuendo.

The two of them broke out in laughter at this inside joke that arose from the many sweaty hours they spent in the cook room, boiling the beans.

Billy loosed a long sigh, adding, “You remember Jeff Lee? Got a little office in a warehouse on Pike Street?”

“Sure,” Jack said. “JK Trading, something like that.”

“Well, he was asking for you. I tried calling you, then I remembered you said you were away for vacation.”

“Why? What’s up?” Jack asked.

“Someone took like eight thousand worth of stuff, but they didn’t see no entry.”

That’s Ghost turf, thought Jack, dailo Tat’s territory.

“No forced entry? Didn’t Jeff call the cops?”

“Yeah, they came,” Billy answered. “The burglary cops, you know. They made a report, told Jeff they thought it was an inside job.” Billy leaned closer and said quietly, “Look, I told Jeff you’re out of the precinct, but he was just asking, maybe you could take a look around. Like a second opinion.”

Jack felt it again, the tension at the back of his neck, the reasons why he had to leave the Fifth Precinct. The Chinatown way, the Chinese mistrust of policemen and government officials, a historical divide covering centuries of corruption in China, and Hong Kong, where they’d refined corruption to an art form.

All the good things he accomplished as a cop here, made possible because he was Chinese.

All the bad things that happened along the way, also because he was Chinese.

Still, he thought he could have made a difference if only he could have kept his Chineseness out of it.

“C’mon,” Billy snapped, breaking Jack’s drift. “What fuckin’ inside job? Jeff works the place with his father and sister. It’s a desk and a coupla chairs, not JC Penney. They deliver to the vendors mostly. They don’t get a lotta walk-in traffic out there.”

“I had enough trouble in this precinct, Billy. I can’t chump some other cop’s report,” said Jack.

“I’m not saying that, but if your own folks really are robbing you, you sure don’t wanna hear it from some white cop who’s laughing inside.”

Jack shook his head at the raw truth in Billy’s words.

“Don’t worry about it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

“I’m out, Billy,” Jack insisted.

“That’s what I told Jeff,” Billy half-protested. “Here, take his card anyway. Call him if you get any bright ideas.”

Pocketing the card, Jack noticed the United National, a Chinese-language newspaper, on the counter. Plastered across the front page were photos of the Kung family murder-suicide. The headline TRAGEDY, reminded him to visit Ah Por, hoping for clarity. “You done with this?” he asked, folding up the newspaper.

“Take it,” Billy answered.

“You heard about the shooting on Division? Players with AK-47s?”

“Yeah, it was on the radio,” Billy remembered.

“What’s up with that?”

“Don’t know. I can check with the Fuk boys later. They’re working the slop room in the afternoon.”

“I’ll call you tonight.”

“It’s Friday,” Billy grinned. “You know where I’ll be.”

Jack smiled. Friday night was always right for Grampa’s, a revered local bar dive.

The sky outside the Tofu King looked ominous again.

Billy put Jack’s containers into a plastic bag, threw up his hands, palms out, and shook his head to refuse Jack’s money.

Jack smiled and thumped his right fist over his heart to say thanks, and backed out through the cold, steamy door.

He took the shortcut down Park Street onto Mulberry, going along Columbus Park.

He didn’t expect them to be there, the old ladies, but he wanted to be sure, and it was along the way. He was right. Not a soul here, the wind too cold, and the leaves long gone from the trees. In the warmer seasons, the old women lined the fence around the park, squatting low on plastic stools, with their charts, and herbs, and the red books containing their divinations. It was much too cold now, and Jack knew Ah Por would be indoors. He remembered her because Pa had gone to her those years after Ma died. Mostly it was for lucky words or numbers, or any kind of good news.

More recently, Ah Por’s readings, in an oblique manner, had provided accurate clues for Jack. The Senior Citizens Center, he thought, stepping away from the park.

The dull red brick building hunkered down on the corner of Bayard under the flat sky, a stunted cousin to the art-deco colossus a block away at Baxter: the Tombs Criminal Facility, also known as the Men’s House of Detention, and Criminal Courts Building. Its imposing facade was seventeen stories of cut limestone blocks, with solid granite at street level, circa 1938.

The red brick building was older, maybe a hundred years old. Its exterior was a blend of medieval-styled stonework, columns, and turrets. All the window frames were painted green. Jack remembered the place as his neighborhood grammar school, Public School 23, five stories of classrooms, auditorium, and cafeteria. Green linoleum throughout.

The school had served many generations of immigrants, including the Irish and the Italians. Ten years after Jack’s all-Chinese class had graduated, the community outgrew the school, redirecting its sturdy rooms to servicing the senior citizens and the various cultural and civic organizations. They served free breakfast to seniors now, at the same lunch tables and benches that Jack remembered eating at as a schoolboy. Jack recalled those free lunches: cheese sandwiches, split-pea soup, macaroni-and-cheese, peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. On rare occasions the kids would get a Dixie cup of ice cream.

When he stepped inside, it was as if the past had caught up with him, then surpassed him. The worn linoleum of his schooldays had been replaced by lighter vinyl tiles. Across the ceiling, hung new lighting, soft, but sufficiently bright for the elderly. The drone of people eating and talking filled the open space. Chung Wah, Chinese radio, played news and weather over the PA system, just under the chatter and gossip.

Jack went toward the back of the room, where he saw that the old kitchen of the public school cafeteria had been refitted with a half-dozen gas-burning wok stations. Against the wall was a long shelf with five large commercial-grade electric rice cookers.

On a bulletin board, in Chinese characters, they’d posted the different menus for every day of the month. Soups: winter melon, lotus root, fish, or vegetables. Main plates: chicken wings, pork, salmon, or beef, pork chops, and Chinese sausage. Fruit of the day was usually oranges.

Jack looked out over the lunch tables, scanning the room for Ah Por, one old woman in a field of bundled gray heads, most of them wearing overstocked off-color down jackets, donated by Good Panda, the company logo prominently screened across their backs. He continued scanning, his eyes sweeping over more than a hundred Chinese seniors slurping their steaming breakfasts of boiled rice congee, jook, dipping the little bits of bread they’d brought along. A free bowl this morning, funded by some charitable organization, city agency, federal food program, or tong. Whatever. Jack was happy to see the elderly eating heartily, jook, the staple of their lives. Jack knew that Pa had come here for a few jooks in his day, if not for the sustenance, surely for the camaraderie.

Abruptly, he spotted her at the end of the bench by the far wall. The oversized down jacket made her appear smaller, huddled over her plastic bowl. When Jack came to her side the other seniors regarded him with curiosity and suspicion, but Ah Por didn’t seem to notice him. Probably her eyes are failing, he thought, although he knew that the secrets she saw had nothing to do with her eyesight.

“Ah Por,” Jack said, just loud enough above the din.

She looked up and after a moment, he saw small darts of recognition in her eyes. A thin, weary smile crossed her lips. He could see that she had none of her instruments of divination, no red booklet or cup of bamboo sticks, but he remembered she sometimes applied face reading to everyday items, and with a clairvoyant’s touch, could provide a clue that, however obscure, proved to be on target.

This time, he needed consolation, clarity, more than a clue. Her words might exorcise the bad kharma clinging to him now.

“Ah Por,” Jack repeated, handing her the United National, splayed open at the dead Kung family’s photos. He pressed a folded five-dollar bill, folded square, into her ancient palm, gave her a smile, and a small bow of his head.

She ran a gnarled finger over the newsprint photos, closed her eyes. Slowly dropping her head to one side, as if straining to hear something, she said, “Fire.” She paused, then softly, “It is a sign of sacrifice.”

Her fingernails played over the text of the newspaper.

“Wind,” she said, “blows away fear.” Jack leaned in at the softness of her words.

“A cleansing is needed. Wash out the regrets. Sometimes it is necessary, to start anew.” Her palm passed over the school-posed pictures of the children.

“There is no fault in this.” Ah Por caught her breath, looked at Jack the way a grandmother looks at a schoolboy. “To be firm in punishment brings good in the end.” She put out her hand and whispered, “Go to the temple, say a prayer, and make a donation. Eight dollars.”

Jack palmed her another five-dollar bill, along with Jeff Lee’s business card.

She rubbed up the card between her fingers, a look of annoyance crossing her face before she closed her eyes.

She said “Malo.” Jack bent closer. “Bad,” she said. Bad, in Spanish? He was confused momentarily, until she opened her eyes, said it again. “Ma lo,” softening the Toishanese accent, meaning monkey.

“A monkey?” Jack asked. “You see a monkey?”

“A picture,” Ah Por answered, suddenly flashing him a puzzled look. “You’ve been shot,” she said matter-of-factly.

Jack was surprised that she knew. “Yes . . .” he started to answer, when she patted his left side under the jacket, where the ribs wrap around the heart.

“It was my arm,” Jack continued.

“No,” she said quietly. “Something else.”

She’s confused now, Jack thought. Could be dementia there.

“It was a while ago,” he heard himself explaining.

“No,” Ah Por repeated. “Not when . . .” Suddenly she started stirring the congee again, spooning up some, taking a slurp.

Jack knew the session was over. He thanked her, patted her gently across the shoulders. She seemed to shiver, and he backed away, leaving her to eat in peace.

She never looked up to see him leave the cafeteria of his childhood, more burdened now with answers he didn’t understand.

Outside, he puzzled over Ah Por’s words as he walked, the smell of Big Wang’s jook and yow jow gwai, fried cruller, in the back of his mind.

Turning left on Bayard, he passed a string of tong basements that doubled as after-hours gambling dens. During the Uncle Four investigation, Jack’s presence down in the dens had compromised several federal probes. His appearance had been duly recorded by DEA, and ATF, but he’d found out a female shooter could have been involved.

Someone, from one of the tongs, Jack figured, had also dropped a call to Internal Affairs, falsely accusing him of shaking down the gambling operators. The accusations had triggered an investigation, and he’d gotten suspended.

Somewhere, there was still a woman in the wind, he remembered, as he crossed Mott.