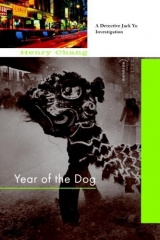

Текст книги "Year of the Dog "

Автор книги: Henry Chang

Жанры:

Прочие детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Year of the Dog

Also by the author

Chinatown Beat

Year of the Dog

Henry Chang

Copyright © 2008 by

Henry Chang

Published by Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chang, Henry, 1951-

Year of the dog / by Henry Chang.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-56947-515-7

1. New York (N.Y.). Police Dept.—Fiction. 2. Chinese—United States—

Fiction. 3. Chinatown (New York, N.Y.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3603.H35728Y43 2008

813’.6—dc22

2008018856

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Mom, who crossed the oceans with quiet courage, leaving behind a war-torn nation, bound for America, to a Chinatown life of piecework, sweatshops, and family. May the Kwoon Yum, Goddess of Mercy, stand beside you always.

Contents

Acknowledgments

0 – Nine

Bodega Koreano

Face and Death

Dog Eat Dog

Black Car, Black Night

Chao’s

OTB

On the Edge

Night Without End

Ninth and Midnight

EDP Avenue B

White Devil Medicine

Roll By

Pa’s Jook

Ma’s Prayers

AJA

Day for Night

Sampan Sinking

Precious

Friends

Golden Star

Dailo ’s Money

Hovel and Home

Pay off

Time and Space

Secret Society

Watch Out

White and Red

Sin

Touch

Crime No Holiday

Xmas Eve

Happy Family

Watch and Wait

Revelations

Deliver U$ from Evil

On This Holy Night

Break Down

Ghost Face

Fade In

God’s General Gourd

Betting Against Time

Blanket Party . . .

Above and Beyond

Gangsta Rap

Bitch Up and Turn

Takeout

Death and Desperation

Life Is Suffering

Space for Time

Courage

Afterlife

Into the Light

The Price of Freedom

Dead Man Walking

Gain , No Pain

Fresh Money

Legal End

Storm

Death Do Us Part

Painkiller

O-Nine

Off – Track – Bleeding

0 – Five

Pieces of Death

Personal Effects

Projects

Hovel

Sampan

Dailo’s Demise

Dead Men Talking

Ballistics and Foreign Sics

Most Precious

Intelligence

Loot – See Lawyer

Touch on Evil

Wise Woman

Wanted Person of Interest

Mercy and Love

White Face

BAI SAN, Paying Respect

Acknowledgments

A blood-thick thanks to Andrew, my brother, the first-born son, for his patience, understanding, and PC Photoshop skills.

A heartfelt thanks to Laura Hruska, my Soho editor, for her keen insight which undoubtedly has elevated my words.

Deep appreciation to Dana and Debbie who continue to believe in the stories.

Great gratitude to Sophia, Mimi, and Bobo, for maintaining the machine.

And as always, love to all my Chinatown brothers, past and present. They inspire me every day.

The Year of the Dog

The Dog is the eleventh sign, next to last in the lunar cycle, the most likeable of all the animals. The Dog is fearless, charismatic, and believes in justice, loyalty, and fidelity.

The year is characterized in the masculine Yang, by struggle, perseverance, and faith.

0 – N i n e

The Ninth Precinct started at the East River, and ran west to Broadway. On the north it was bounded by Fourteenth Street; on the south, Houston. Within these confines, the neighborhoods were the East Village, Loisaida, NoHo, Alphabet City, and Tompkins Square. Anarchists, artists, students, and the low-income working class all lived together, sometimes tenuously, until their breaking points made the Daily News headlines.

The detectives who worked in the Ninth were accustomed to dealing with multicultural scenarios, the daily struggles of blacks and whites, browns and yellows. The scattered Asian presence within its boundaries consisted mostly of hole-in-the wall Chinese take-out joints, Korean delis and dry cleaners, Japanese sushi spots, and even what was probably the last Chinese hand laundry in New York. In the Village, Southeast Asians peddled T-shirts, punk-rock jewelry, and drug paraphernalia. Indians and Pakistanis ruled over the newspaper stands.

Jack Yu had been assigned to the Ninth to cover the holidays. He leaned back from his computer desk in the detective’s area and closed his eyes. On Thanksgiving Day, the last hour of the overnight shift was the longest. His nagging fatigue was spiked with uneasy anticipation.

Homicides in Manhattan South, or diverted from Major Case, were only a phone call away.

He pressed his trigger finger against his temple, working tight little circles there. Computer statistics scrolled dimly inside his forehead, the blunt, logical CompStat analysis of why and how people killed each other in New York City.

There were hundreds of murders in the five boroughs each year; closer to two thousand in the early days of crack cocaine. The records indicated that people killed because of:

Disputes 28%

Drugs 25%

Domestic violence 13%

Robbery/Burglary 12%

Revenge 10%

Gang related 8%

Unknown 4%

Entire lifetimes were reduced to an NYPD short list of cold percentages, time and location, gender and ethnicity.

Just the facts. Leave the speculation to the beat dicks.

The statistics indicated that women were more likely than men to murder a spouse or lover, and:

Male killers favored firearms over all other weapons.

Brooklyn, a.k.a. Crooklyn, had more killings citywide than any of the other five boroughs. 46%.

Saturday was the most popular day both for killing and dying.

Men and boys perpetrated 90% of the murders.

The deadliest hour was between one and two AM .

In half the cases, the killer and victim knew each other.

In 75% of cases, the perp and the vic were of the same race.

Homicides were concentrated in poorer neighborhoods.

Most of the killers had criminal records.

A third of homicides went unsolved.

Asians, who made up 11 percent of the city’s population, accounted for 4 percent of the victims, and oddly enough, for 4 percent of the killers. The number four, in spoken Chinese, sounded like the word for to die.

Jack knew working the Ninth Precinct, the 0-Nine, wouldn’t be like working anticrime in Brownsville, or East New York, where killings were commonplace, and cops were used to tabulating bodies on a weekly basis. The 0-Nine, according to the Compstat analysis, didn’t have a lot of homicides, but kept pace with other precincts with regards to all other types of incidences, like armed robberies, burglaries, domestic disputes, teen violence, and drug dealing.

He grabbed at and massaged the knotted cords in the back of his neck, taking a deep boxer’s breath through his nose.

The 0-Nine house seemed to be a good fit for him, a welcome surprise. He wasn’t expecting any of the problems he’d had in the Fifth Precinct. He figured that his exploits there, which had earned him a gold shield, would have preceded him to the new stationhouse, earning him a small measure of respect.

Jack got up from the desk and went toward the rear window, smoothly swinging his hips and legs down into a long bridge squat, a Shaolin-style stretch. His lower joints and ligaments popped as he straightened up, watching the frozen gray Alphabet City morning seep in through the window.

One call came into the precinct. A junkie from the projects had been found dead of an apparent drug overdose in an Avenue D shooting gallery, but Narcotics swept it up as part of a larger operation. The dead junkie was their CI, their confidential informant.

The remainder of the shift passed quietly, punctuated only by crackling voices from the squad radio at the duty desk out front. Nobody killed anyone in the precinct on this overnight shift, but on the Lower East Side, Jack knew, violence was only one wrong look, one bad intention away.

Out by the duty desk, the uniforms of the day shift rolled in.

Jack signed out as they started to muster for roll call. He was thinking of the hot chowder at Kim’s when the first frigid gust of East River wind slapped him in the face.

Bodega Koreano

Kim’s Produce was a mom-and-pop Korean deli on Tenth Street, a few blocks from the Ninth Precinct stationhouse. It was 9:18 AM on the Colt 45 display clock, well past his twelve-hour tour, when Jack joined the cashier’s line with his take-out container of hot clam chowder. A small television set showed the Thanksgiving Day parade. He sipped the steaming soup as he waited, watching the TV. Jack had mixed thoughts about the holiday seasons in the city. These were celebrations, but for many people the seasons were very sad times. There were two cities here—one rich, one poor, each spiritually if not physically segregated from the other.

Jack watched the Macy’s Parade march down Central Park West, past the stately and formidable buildings whose names rolled out: Majestic, Prasada, Dakota, San Remo, the landmarks of the rich and fabulous, private balconies with front-row views. The majorettes fronting the marching bands moved briskly down through the Twentieth Precinct, toward the old Mayflower Hotel, then on past Trump International, where top-shelf guests reserved midlevel suites for holiday packages at a thousand a night, so that their children would be thrilled by the giant cartoon balloons floating past their floor-to-ceiling double-paned glass windows. The Pink Panther. The Cat in the Hat. Barney the Dinosaur. Sonic the Hedgehog, who had an appetite for lampposts along Central Park.

Down below, at street level, two million of the hoi polloi gathered along the parade route, crowded and penned-in along the sidewalks, in the bitter cold. Tourists and middle-class families from the outer boroughs saw the floats rolling by—Big Bird and Santa Claus, and comic-book heroes floating in the sky.

The parade moved south toward Times Square, passing through the Midtown Commands, Manhattan North and Manhattan South. It would all end, Jack knew, at the Macy’s store at Herald Square, where there would be backup from the Tenth and Thirteenth Precincts, and, of course, plenty of overtime uniforms managing the crowds, working the barricades and the subways.

Much farther downtown, Jack knew, there were no luxurious hotel rooms, no balloons or floats. On the Lower East Side, Loisaida, the holidays found citizens of the 0-Nine at soup kitchens and food pantries, at the Bowery Mission, where the hungry, homeless families and the poor eagerly awaited a traditional hot turkey meal with all the trimmings, with the rest of the citizenry giving thanks, There but for the grace of God go I. Holy Cross, St. Mary’s, St. Mark’s Shelter: Soup kitchens scattered throughout the precinct gave them all something to be thankful for, even for one day.

The holidays were a humbling time for them; the displays of cheery celebration, and religious and commercial spectacles were not theirs. To them it was only another year of struggle passing by.

In Chinatown, most Chinese people didn’t celebrate a traditional Thanksgiving, but the holiday provided an excuse for them to get together and feast on a meal of seafood, pork, chicken, and baby bok choy. Lobster Cantonese instead of turkey, rice instead of mashed potatoes, with winter melon and lotus root soup. Extended families gathered around da bean lo, hot-pot casserole-style cooking.

Jack didn’t have fond memories of the holidays. Pa had never felt he had a lot to give thanks for, and hadn’t been a big believer in Christmas either, so Jack rarely received gifts. His one big thrill had been getting something from the Fifth Precinct PAL, when he’d line up with all the other “deprived” Chinatown kids hoping for a holiday handout. He remembered one year getting trampled in the mad rush of the older kids and parents to get a free toy. Trampled for a Popeye-the-Sailorman figure. He cried, but was still happy to have the free gift. When he brought it home, Pa had derided him for getting run over for a stupid gwailo doll.

Jack reached the cashier at the same time that his cell phone jangled and broke his reverie. He paid for his soup, and flipped open the phone.

It was the dayshift duty sarge, telling him patrol had responded to a call and found multiple bodies, very dead, at One Astor Plaza, down from the Barnes & Noble bookstore.

Sergeant Donahoe was in the blue-and-white downstairs at the scene.

Manhattan South was responding to holiday road rage auto fatalities on the Westside Highway, so they were reaching out to Jack.

“On my way,” Jack said, pocketing the phone.

He finished the soup in a big swallow, turned up his collar, and emerged onto the frozen street. He made his way west, through the East Village, the icy wind already tearing at his face, icy needles prickling his eyes every step of the way.

Face and Death

One Astor Plaza was a twenty-story curved glass tower, a luxury high-rise condominium building seamlessly shoehorned into the middle of a neighborhood crossroads that spread out to include the Public Theater, the NYU and Cooper Union campuses, the East Village and NoHo. It was a doorman residence, had security in the lobby, and a concierge behind a black marble counter. A Commercial Bank branch anchored the rest of the main street floor. A two-bedroom unit cost 1.5 million dollars and the project had sold out during construction.

The sculpted neo-modern glass building towered over the main avenues that ran north-south through Manhattan, over the major eastside subway hub, and dominated that entire commercial corner of Cooper Square.

A big overweight man, Sergeant Donahoe, stepped out of the squad car.

“I’ve got Wong up there,” he said.

Police Officer Wong, Jack knew, was a rookie patrolman, a Chinese-American portable who could speak several Chinese dialects.

“Eighteen-A,” Donahoe continued. “You got the building manager, the security guard, the grandmother, all up there. The fire lieutenant’s at the fireboard in the lobby. Talk to him first.”

Jack sucked in a deep gulp of cold air. “What do you have?” he asked, steeling himself.

Donahoe gave him a sad look and shook his gray-haired head.

“It’s the whole family . . .” He paused and before he could continue, Jack had turned and was heading for the lobby.

The fire lieutenant, another tall Irishman, explained that they’d come to the scene because a ceiling smoke detector had activated and the alarm had gone out through the fireboard.

“When we got to the floor, there was no smoke,” he said. “But the ceiling detector was a combination type that also detected carbon monoxide.”

“So it was the carbon monoxide that set it off?” Jack asked.

“We took several readings,” the lieutenant said. “The CO levels were over eighty parts. And ten parts is unsafe.”

“Eight times lethal,” Jack noted.

“Hell of a thing on Thanksgiving Day. Anyway, my men are done upstairs.” The lieutenant added, “We’re just resetting the fireboard now.”

“Thanks for your help,” Jack said, grateful for the heads up as to what he was walking into.

Jack had heard many other cops deride the firefighters as thieves, referring to how they would take money and property from fire scenes. Quite often control of a crime scene that involved a fire was contested between the two commands, cops versus firefighters. Jack never saw it; he thought the firefighters had a tough job entering burning buildings, especially in winter. Even though he knew that the FDNY was still segregated—mostly white, mostly Irish—he had to give them respect for the hazardous jobs they did.

The elevators were fast, industrial quality steel polished into an elegant design.

The door to 18A was open, with yellow Crime Scene tape running across it. The firefighters had cranked open all the windows and evacuated all the residents of the eighteenth floor. P.O. Wong stood by the door with the building manager who nervously jangled a set of master keys. Jack introduced himself to the manager, nodded to Wong.

“I’ll need a statement from you,” he said to the manager. “Also, the security report, and information about the tenants.”

The manager was in shock. His face was pallid, voice shaky. He said sadly, “Certainly. I’ll be in my office on the main floor. It’s a terrible, terrible thing.” He walked slowly to the elevator.

Wong, who was shorter than Jack and built like a bulldog, pulled off one end of the yellow tape.

Jack asked him, “Wong, when accidents happen, do you think it’s destiny?”

P.O. Wong answered, “Well, this sure wasn’t an accident, but it could be destiny.” A puzzled look cross Jack’s face when he saw the Chinese grandmother seated on a folding chair just outside the apartment door.

“We had a hard time calming her down,” Wong told him. “She only speaks Taiwanese.”

Jack put his pen to his notepad. “Tell it,” he said quietly, glancing at the old woman.

“Grandma there gets a panicked phone call from Taiwan,” Wong began. “The in-laws are freaking out that something bad was going to happen here. They had received a letter from their son, the tenant, just today.”

Jack looked up from his pad.

“It sounded like he was saying good-bye,” Wong continued.

The old woman glanced at Jack, who was running worst-case scenarios in his mind.

“It took her a coupla hours to get here from Jersey,” Wong went on. “And then there was a delay at the front desk, the language problem, and they wanted to make sure who she was, things like that. They called upstairs, there was no answer. Then the building manager came up with the grandma and security, and used his master keys. Both locks were locked. When they opened the door the corridor detector went off.”

“So then the fire department arrived,” Jack commented.

“A few minutes after. So then we went into the apartment.”

Jack stepped inside the apartment, followed by Wong. At their feet was a crumpled-up quilt, crushed against the inside of the door.

The old woman still sat in stunned silence as they passed her. Jack scanned the room. It was very cold inside. The windows were wide open and lightweight curtains danced in the wind. Jack noticed an aquarium with eight Chinese goldfish floating belly up.

The floors were covered with off-white carpeting throughout.

The big room beyond, the open living room, was bathed in the dull gray morning light that flooded in through floor-to-ceiling windows, a flat wash that muted the few touches of color the room held. The modern, understated furniture consisted of a navy-blue L-shaped couch with a matching ottoman at one end, a wide-screen television, and a glass coffee table. One wall held a built-in shelf unit that displayed porcelain vases, terra-cotta figurines of Chinese men on horseback, and a miniature red, white, and blue flag of Taiwan. Everything was neat, like a deluxe hotel room after a maid had been through it. To one side was a kitchen area, set off by an island with a granite countertop that housed a sink and dishwasher. A stainless-steel refrigerator and matching cabinets lined the walls.

At the far end of a hall were the bedrooms.

Wong continued, “The son’s letter described some bad business deals, and told them he’d lost money in the stock market.”

Spread across the range top and the granite counters were an array of saucepans, and two small Chinese woks. There were ashes and charred lumps in all of them. Jack saw a box of wooden kitchen matches and a small can of lighter fluid. Someone had cooked up eight containers of charcoal briquettes on the range, dousing them up with lighter fluid to keep them all going.

“There’s an empty bag of charcoal behind the counter,” Wong said. “The son and his wife were depressed over their losses.” He continued, “The two children went to a fancy private school.”

Jack walked into the smaller bedroom.

“How old were the kids?” he asked.

“Five and six,” Wong said solemnly. “Two little boys.” He was disciplined enough to brief Jack with the factual information, but smart enough to keep his opinions and personal feelings to himself.

The boys’ room had twin beds with New York Yankees pillow shams and matching duvet covers. Between the two beds was a nightstand with a Mickey Mouse table lamp. A desk held a computer and over it were shelves full of children’s books. Stuffed animals were displayed on the dresser and a few large ones stood on the carpet: Pooh Bear and Tigger, Barney and Big Bird. Posters of Thomas the Tank’s adventures hung on the wall.

Jack felt his adrenaline building. He was thinking, Murder-suicide, bad enough, but why take the kids? Were they staying together for the next life? He took a deep breath, took the disposable camera out of his jacket pocket, and went toward the last room.

Heavy curtains were drawn back. The room was even colder than the rest of the apartment. The master bedroom was spacious enough so that the bodies didn’t seem to take up much room in it. A woman and two children lay on a large bed. A man was slumped over on a settee. Jack took a photo of the area, then three more individual shots as he approached the bed. He observed a bottle of NyQuil on one of the two night tables.

The Chinese woman lay on her right side, her left arm draped across the bodies of the two boys. They were supine, their arms at their sides, dressed in school uniforms. The three of them looked as if they were asleep.

In the far corner of the room were two large red ceramic bowls with dragon designs on them, strategically placed. Jack saw ashes in both. He leaned in closer and took some head shots of the victims.

The woman’s eyes were sunken and shadowed. She’d been crying for a long while. She’d dressed conservatively in slacks and sweater top. Jack guessed she was in her mid thirties. Over on the settee, the man was hunched, head down, his open eyes staring at the carpet. He had vomited. He appeared to be in his early forties.

The vomit was dark colored, and Jack guessed from the crust that had formed that it had dried for at least a day.

Opposite the body was a large Chinese armoire that blocked off a neat home-office area: desktop with computers, a printer, and a set of filing cabinets. On top of the cabinets was a stack of books. One was entitled The Day Trader’s Bible.

Jack used up the rest of his film, taking shots from different angles. He believed photos were a more efficient way to preserve his impressions than written notes and he wanted to take them himself before the crime scene became crowded with the coroner’s people and the crime-scene team.

When he was in Chinatown, Jack would drop the camera off at Ah Fook’s Thirty-Minute Photo, and Fook Jr. would develop his order first while he went next door to the Mei Wah, got a nai cha tea, and watched the gangboys roll by.

He dropped the disposable camera back into his pocket.

Outside the bedroom, Wong said, “Sarge notified the ME about twenty minutes ago. They’re en route in the meat wagon.”

“Okay,” Jack nodded. He knew Wong wasn’t being crude and insensitive. It was just cop talk, jargon they used to take some of the edge off of a traumatic event.

Wong moved toward the main door and the old woman, who was now weeping quietly. Jack went to the window wall of the living room. The view swept north toward the Empire State Building and the jumbled rooftops and billboards of the big city beyond.

The streets below were bustling, a tangle of pedestrian traffic crowding the intersection. The city was in a holiday season rush, and people poured out of the subways and buses, jamming the streets in every direction.

The world goes on, Jack thought. An entire family offered up to the gods, gods of greed and desire, and the world stops not one second for condolences. Too bad.

It wasn’t the first time Jack had seen dead children, but it was the first time he’d witnessed the end of an entire family. That they happened to be Chinese brought it closer to home, as he assumed it did for P.O. Wong. But as cops they instinctively protected themselves.

Cops got paid to sop up the daily horrors and bloody atrocities that the white-collar suits and ties didn’t want to deal with. Cops became hard-hearted, kept a professional distance from the victims, and worked in a way that didn’t affect them emotionally. Deeper involvement was a real danger that could lead to overzealousness. Frontline cops became numb to the daily onslaught of unspeakable crimes that crossed the desk blotter day and night. Fifty thousand arrests a year. In a city where teenage mothers disposed of their babies in the garbage, parents were known to kill their children and themselves out of anger, depression, desperation, very often in the grip of an alcohol-and-drug-induced rage.

The Taiwanese, like other Chinese, were obsessed with success and money. The present tragedy was the result of depression over the imminent loss of a certain lifestyle, but it was as much about shame, about losing face. Ma’s Buddhist beliefs came back to him: greed and desire. The Buddhists taught that wanting and having, the material world, could only lead to unhappiness. Life was suffering, and suffering came from desire, the desire for things, for hopes unfulfilled. Eliminate desire, and you will eliminate suffering.

Suicide was not uncommon in America, Jack knew. Most were men, and they shot themselves. Then there were drug overdoses, risks taken to disguise a death wish, and, finally, assisted suicide from those who believed in the right to die.

At the apartment door, Jack saw the ends of the packing tape that had been used to secure a quilt over the door so none of the carbon monoxide could escape.

Eliminate desire.

He left Wong at the scene and went down to get a statement from the building manager. He knew the follow-up paperwork at the precinct, plus the reports from the coroner’s office, the notification of next of kin, the certificates from the funeral parlor, everything, would take up his next few shifts.

Finally, after sixteen hours on the job, with weariness pulling at his eyelids, he called for a Chinatown see gay, car service.

* * *

The Chinese driver spoke Cantonese, and took him straight out to Sunset Park, Brooklyn’s Chinatown, without asking directions. Exhausted, Jack powered down the window and let the icy wind slap him awake.

He’d been thirsty long before he reached his studio apartment, but once inside he went directly to the cupboard in the kitchenette, took out a few sticks of incense, and lit them. He shook off the ash and fanned the wiggling tails of smoke as he planted them at the little shrine he’d made for Pa on the Parsons table near the windowsill, where he’d placed an old photo of his father dressed in Chinese-styled tong jong clothing.

Pa was now seven weeks buried in the hard ground of Evergreen Hills.

Jack’s next visit to the cemetery wouldn’t be until mid-January, on what would have been Pa’s birthday.

This sad day reminded Jack that he, too, though only twenty-seven, was at the end of his bloodline, a solitary remnant of the Yu clan, whose ancestry retreated back through the generations.

Eighty-eighth cop of Chinese-American descent. A lucky number, he’d thought. But it hadn’t worked out that way.

He could still hear the old man’s words. “Chaai lo ah? Now you’re a cop?” Pa had said with derision when Jack first put on the blue uniform. “Chinese don’t become policemen. They’re worse than the crooks. Everyone knows they take money. Nei cheega, you’re crazy. You have lost your jook-sing– American-born—mind. I didn’t raise you to be a kai dai—punk idiot—so they can use you against your own people.”

I never took any money, Jack hadn’t found the chance to say to his father.

Jack bowed three times before the shrine, then quickly found the Johnnie Walker Black and poured a tumbler full, cracking open a can of beer to chase it.

The whiskey had only coated his throat with fire. He told himself that the beer would chill him out, would let him sleep better, as he drained the can. He’d lost any appetite he’d had at the crime scene. Now he sat on the edge of his convertible couch nestled in the far corner of the studio. He kicked off his shoes, trying to focus, to make some sense of the days and weeks gone by since Pa’s death.

Four months earlier, what began as a hardship transfer to Chinatown’s Fifth Precinct to be closer to his dying father, had ended up with a promotion. Then he’d been transferred to the Ninth.

Bad memories from the period in between twisted together as the alcohol reached his brain. He drew the blinds against the afternoon light.

When he closed his eyes, his mind drifted. He fell asleep on the couch.

His sleep was pervaded by a restless disconnected feeling, fitful, punctuated by dreams.

He was seventeen again, running across rooftops at twilight, with Tat Louie, and Wing Lee. Three bloodbrothers, hingdaai. Tat was throwing pebbles at the tenement windows and they were shrieking with juvenile laughter as they ran; three Chinatown boys, mad with mischief, having the time of their young lives. Then suddenly, there were the ugly, sneering faces of Wah Ying street-gang members, wielding nasty 007 knives. A swirl of images: Tat, fighting, and Wing, being stabbed. For himself, a quick blackness as he was smashed across his forehead, blood running into his eyes. Then the scene faded to a Chinatown funeral parlor. Wing in a casket, his face dead white, and Tat running out, past the pallbearers, followed by the wailing of Wing’s mother. The incense smell of death.

He was watching his youth flash by, viewing it like a camcorder tape, the pictures harsh, unforgiving. Suddenly, Chinese cursing from somewhere, a sound he’s heard before. Pa’s voice.

Jack felt his body quake uncontrollably. The images flashed in his brain like sparks from a live wire. Japanese soldiers charging forward, samurai swords raised, hacking at Chinese babies, lunging at Chinese women with their bayonets, raping them. The flag with the red Rising Sun fluttering violently in the gale. Butchery. A thousand Chinese heads bouncing and rolling down a blood-slicked slope. And he is sliding, falling.

But this is Pa’s nightmare.

There is nonstop screaming and yelling, Say yup poon jai! Pa cursing, Jap bastards! Jack is at Pa’s side then, punching away at the bayonets and swords, until he bolts upright on the couch, nearly kicking over the boom-box radio, slowly realizing that it’s his own voice barking into the shadowy dark of the small room.

He sat up for a while, caught his breath, and after downing another shot of Johnnie Walker Black, gradually fell back to sleep.

The final dream was short, a twisted vision of Tat, a Chinatown gangster in a black leather trench. Tat “Lucky” Louie, offering him a big bag of money which he didn’t accept. Tat, who’d become an ugly liability.