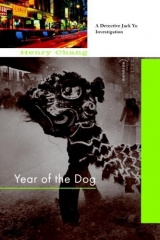

Текст книги "Year of the Dog "

Автор книги: Henry Chang

Жанры:

Прочие детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Dead Men Talking

When he got back to the 0-Five there was a big file envelope waiting with his name on it. The captain had signed for it and left it on the desk where Jack had been working the case.

The Medical Examiner’s reports were inside, a thick sheath of papers and photographs; six sets of clinical observations and explanations, one set for each victim.

Except for the old man, the other five corpses all had gang tattoos. This didn’t surprise Jack. He knew they were Ghost Legion, gwai, Lucky’s crew. Tat, Cham, and big Kong all had the Chinese word ghost tattooed onto their left biceps. The gang tats were black ink, but in different script or block styles.

gwai

What interested Jack was the tats on the other players: the two Jung brothers, and Koo Kit. Each had a quarter-sized red star tattooed on his back, just below the right shoulder. An eight-pointed star. Old tattoos, Jack could tell, because of how the red tint had faded.

None of them had the word ghost tattooed anywhere.

But they were all Ghosts, had to have had criminal records. Jack knew their rap sheets would blow their shady covers.

Jack noted the ME’s indications that Lucky and his crew all had alcohol and Ecstasy in their systems. Again, not unusual for them.

They’d indicated gun-shot residue on Cham’s left hand. A lefty. The other shooters were all right handed.

Jack remembered what a miracle it had been that no civilians had gotten hurt. Thank the blizzard for that.

The comparative reports from the Medical Examiner’s office and the Crime Scene Unit listed Cause of Death (COD), what or who caused the death, and offered a tentative scenario, how it had probably happened.

They’d matched the fingerprints on the shell casings to the shooters, making it clearer.

Ballistics and Foreign Sics

Except for Lefty—Cham—all the other gang vics had suffered multiple gunshot wounds. Lefty had expired due to a single kill-shot wound determined to have come from the .357 Magnum revolver of Joey Jung. The magnum slug had drilled a hole in Lefty’s chest and exploded half his heart out through his back.

Kong, the big Malaysian, had taken eight hits from four different guns; two in the chest from Jimmy Jung’s nine-millimeter, two more in the stomach from Koo Kit’s .380. Joey Jung had shattered Kong’s right hip with two .357 Magnum rounds, but it was a pair of high-velocity .22-caliber slugs that had put out the big man’s lights.

Two twenty-twos through the right eye.

They’d extracted the killshots from inside Kong’s skull, where the spinning metal pieces had torn up half his brain matter before fragmenting, flattening against bone.

Jack imagined the scene with wicked clarity, tracing the gun battle in his mind, seeing all the players with the star tattoos exchanging gunfire with Lucky’s crew. It had to have happened so fast Tat never got to draw his gun. Thirty seconds, less than a minute.

Jack saw a chain of actions and reactions pulling the gangboys along helplessly, like puppets. Who was the first shooter? They hadn’t found any eyewitnesses. Wait for Tat to talk? If ever?

The Jung brothers had both been seriously wounded by the heavy scattershot from Kong’s shotgun, but it was Jimmy who’d borne the brunt of the blasts. A dozen pellets had ripped open his chest and pierced his heart.

Joey Jung had three gaping wounds from the shotgun, but the two nine-millimeter headshots from Lefty Cham were what killed him. Except in right profile, he no longer bore a resemblance to his brother.

Koo Kit had taken two nine-millimeter blasts to his left shoulder and leg, sureshot Lefty drilling him, probably, as he was angling toward the alley. He’d made it partway to Doyers when four .22 hi-vels ripped through his back and riddled his heart from behind.

Twenty-twos. They’d recovered two slugs intact, in perfect shape.

Jack remembered the body sprawled near the bend in the alley.

The ME had noted that all the .22-caliber bullets had penetrated at an upward angle, as if the shooter was on one knee, or shooting from the hip. Since they hadn’t recovered any .22-caliber shell casings, Jack figured the gun had to be a revolver.

Somewhere in the puzzle was a missing .22– caliber piece, and a shooter in the wind who was responsible for two kill shot homicides and a coma victim.

The old man, Fong, didn’t appear to be a homicide. If he was, they’d never be able to prove it. The ME had ruled COD as cardiac arrest. Instant death due to a massive heart attack. He never knew what hit him. A quick death, better than a slow one. Who was the perp? God?

Closing the envelope, Jack called One Police Plaza, and then Manhattan South.

Most Precious

Bo was disappointed that Sai Go hadn’t shown up that week. She’d brought in a box of don tot, egg custard tarts, and planned to take him to Golden Unicorn for yum cha, tea. She’d guessed that he’d gone on another gambling junket with his friends.

When the two men in suits came through the door, she thought they were walk-ins, even though she’d hardly ever seen suits walking into the New Canton. A Chinese man and a white man, quietly glancing around the shop. Abruptly, the Chinese man asked for the owner, and KeeKee beckoned him over, a curious look on her face.

They spoke in low voices, and after a few moments, all looked at Bo.

Bo’s first fear was that the men were immigration agents.

Someone had betrayed her and they were here to send her back to China, or to extort money.

She was puzzled when the Chinese man explained that he was a lawyer, and that he was a friend of Sai Go. The Caucasian man, according to the lawyer, was an agent for an insurance company. They had some papers for her to sign, and items to turn over.

The Chinese lawyer, named Lo Fay, explained that Sai Go had suffered a sudden heart attack, and passed away.

Bo trembled as sadness came over her. The jade gourd and the Kwan Kung talisman had failed.

“You are the beneficiary of his life insurance policy, and according to his will . . .”

She started to weep, and KeeKee put an arm around her, comforting her.

“Fifty thousand dollars . . .”

She heard his words as if from a distance, in fragments, unable to comprehend the numbers. She remembered Sai Go’s last visit, when he had gifted her with the betting ticket from OTB. He’d had a smile on his face.

She trembled uncontrollably through her tears, and could not help thinking of her family in China.

“He’d had no relatives to consider.”

She felt ashamed that she was already thinking about paying off the snakeheads, but she found new hope in Sai Go’s generosity. She might finally bring her daughter and mother to America.

“Evergreen Hills cemetery,” Lo Fay was saying, “by the new Fong Association section.”

KeeKee told Bo to go home and rest and grieve privately but she insisted on finishing out the day.

She vowed to herself to pay respects in the morning, at Sai Go’s grave. She promised to sweep around his tombstone every spring’s ching ming, memorial period, at every anniversary of his passing, for the rest of her life.

At the end of the day, an old Chinese man came to the salon and presented Bo with a package, saying it was from his friend Fong Sai Go. She thanked him and he left. Removing the brown mahjong-paper wrapping, usually used by old-timers to cover the playing surface, she saw a polished mahogany box with a mother-of-pearl Double-Happiness symbol inlaid across the top. Inside the box was the gold-plated talisman card she’d given to Sai Go long ago. Beneath the talisman was a large red lai see, lucky-money envelope.

The lai see was thick. She opened it and saw neatly banded stacks of hundred-dollar bills. Lucky money from an honorable caring man who’d run out of time. She quickly put everything back into the Chinese box and left the salon.

Outside, the evening was black, and frozen. She cried all the way home, her hot tears mercifully wiping away the hopelessness that had shrouded her heart.

Intelligence

Reaching out to the Gang Intelligence squad, Jack was able to access the computer records specific to Chinatown gangs.

The Ghost crew run by Lucky had had serious charges filed against them that were mostly dropped, dismissed, or pleaded-out. Assault, robbery, promoting an illegal gambling enterprise, possession of controlled substances, and weapons violations. Suspected in numerous assaults and homicides. The On Yee was rumored to have good white lawyers on their payroll. Knowing this, Jack scrolled on and clicked deeper. Under IDENTIFYING TATTOOS AND MARKS, he entered “red star.”

The Stars popped up, a dozen thumbnail pictures of adolescent Chinese faces. The Stars were thought to be one of many small gangs, the off-shoot younger brothers of outcast Chinatown gangs that had vied for leftovers along the stretch of East Broadway before the Ghosts and the Fukienese came along.

The Stars, with less than twenty members, had mostly petty criminal records: disorderly conduct, petty larceny, attempted assault, criminal mischief, nothing as hard-core as Lucky’s Ghosts.

Maybe they just hadn’t gotten caught with the serious stuff?

Sometime after 1989, their activities ceased. Long-standing warrants for their top leaders went for naught. As if they’d disappeared.

The Jung brothers, appearing younger, came up quickly as he scrolled. They were six years younger, according to the dates on the pictures. They had been charged with criminal mischief and menacing. The circumstances were not identified, and the accusations were later dropped when the complainants declined to press charges.

Other Star members had also been arrested for criminal mischief, and those charges had also been dropped.

Jack noticed that one member of the gang, Keung “Eddie” Ng, was listed at four-foot seven inches tall. A shorty. He’d had a juvie file as a teenager that revealed he had been arrested for criminal mischief, for spray-painting red graffiti stars all over the interior of a Chinatown warehouse. He’d tripped a silent alarm. They’d also charged him with a B&E, breaking and entering, even though they couldn’t figure out how he’d gotten inside.

All the doors and windows were still locked when the cops arrived.

Under IDENTIFYING MARKS, the record also indicated he had a small tattoo of a monkey, like Curious George, on his left wrist.

Finally, the address given by little Keung—“Eddie”—was 98 East Broadway, the same as the current address for Koo Kit, the victim who’d been shot in the back. Jack deduced that Little Eddie was good for whatever had happened in the alley. The vicious little twenty-twos, shot upward by a shorty.

Ngai jai dor gai, mused Jack, short people are cunning. The Chinese say that short people are more clever because their brains are closer to the ground, and they see reality more clearly.

Jack printed out the mug shots from Keung “Eddie” Ng’s file.

Loot – See Lawyer

Lo Fay, the lawyer, sat behind an old metal desk in his small windowless office. He wore his hair in a comb-over and spoke through a crooked smile.

Listening to the man, Jack saw him for the shyster lawyer that he was.

“He was dying,” Lo Fay said of Fong Sai Go, his client and friend. “He had no one else to leave it to, and he thought giving it to her was the right thing.”

“He was an honorable man?” Jack suggested. “He wanted to do something good in his life?”

“Right.” Lo Fay kept the squinty-eyed smile on his face. “She was kind to him.”

Jack gave him a knowing look. “What did Mr. Fong do for a living?

“He used to be a waiter.”

“Used to be?”

“He retired years ago.”

“So, what?” Jack asked. “He was collecting social security, or something?”

“I’m not sure about that.”

Jack leaned in, saying quietly, “What about the gun he had?”

“I don’t know about any gun,” said Lo Fay, losing the smile.

“Why do you think an old man like him would carry a gun?”

“No idea,” smirked Lo Fay. “Maybe he had no faith in the police.”

Jack grinned quietly, made a fist, and rubbed his knuckles. “What exactly did he retain you for?”

Lo Fay took a breath, saying matter-of-factly, “To do the will, and to handle the life insurance.”

Jack waited for him to go on.

“He wanted me to arrange immigration matters for her. Applications, like that.”

Jack said, “And you have a check to show that he compensated you for these services?”

“I’m not looking for trouble, officer,” said the lawyer looking away. “He paid me in cash.”

“How very Chinese.”

“Everyone prefers cash,” Lo Fay said. “It’s the American way.”

“And you work for the Association?”

“Don’t misunderstand. I only handle the Association’s accounts with the funeral parlors.”

“Right, the death business,” Jack said knowingly. “It’s a complicated affair.”

“Lots of legalities when you die,” he answered.

“Like who gets what?” Jack added.

“Like who follows up, who takes care of the spirit,” said Lo Fay.

The spirit? thought Jack.

“You have to consider Chinese tradition,” the lawyer said. “The afterlife is just as important.”

Jack thought of Pa’s death, and the cemetery at Evergreen Hills. He leaned away from the charlatan lawyer, saying directly, “You know what it’s like in the afterlife?”

“Well, no. But people should be optimistic at death.”

Optimistic?

Both men were quiet a long moment, the interview at an awkward end.

Jack shook his head contemptuously as he left Lo Fay’s office. He remembered the Kung family’s murder-suicides, the brutal killing of the delivery boy, Hong, the bodies around OTB, and couldn’t find any optimism about death.

Touch on Evil

The two watches taken from the Jung brothers ran like they were synchronized, accurate to ten seconds of each other. Jack figured that one of the brothers had set both watches.

The Rado found on Lucky had stopped at 4:44 that afternoon. The worst numbers a Chinese can get, Jack thought. Lucky’s time really had run out.

Jack decided to bring the watches along, just to see what the old wise woman would get from them.

The little copper-colored slug was a .22-caliber long rifle round, a high velocity bullet generally used in target-shooting competition. Jack closed his hand around it, shaking it in his fist. The small piece of metal bounced around. It weighed next to nothing, he thought. It was barely bigger than a grain of nor may, sticky rice, yet the minute projectile figured prominently in the deaths of two people, and had reduced Lucky to a comatose state.

Wise Woman

He found Ah Por at the Senior Citizens Center, on a bench near the kitchen volunteers who were still ladling out the last of the free congee.

He showed her the watches first. She held them up to the light, frowning at the rectangular black watch faces. Black. Bad luck times three, he imagined her thinking. She said, “Gee sin” quickly, and made a flapping motion with her free hand, fanning herself. Gee sin, a paper fan. Another arcane clue, mused Jack. Paper fan? He knew better than to question further, and took back the watches.

He removed the twenty-two bullet from the plastic ziplock bag and handed it to her.

Ah Por cradled the little slug in her palm, bouncing it gently like she was checking its weight. She closed her gnarled fingers around it, and squeezed. Closing her eyes, she jerked her head slightly, as if surprised.

“Ma lo,” she said distinctly, and this time it was clear to Jack she meant monkey. Bad monkey, just as he’d suspected, and was now certain. Keung “Eddie” Ng was the missing shooter.

Jack thanked Ah Por, folded a five-dollar bill into her bony hand, and exited the center through the crowd of old gray heads.

Wanted Person of Interest

Back at the 0-Five, Jack reviewed the Gang Intel files, and put Eddie’s photo, tattoos, and name on a wanted bulletin that would reach out electronically to a million eyes, searching into the wind after a clever monkey.

Mercy and Love

Bo waited on Mott Street until the Temple of Buddha opened its doors. Inside, a recorded chant came from behind the large wooden carving of the Goddess of Mercy. Bo burned some incense, kneeled before the goddess, and recited the prayers for Sai Go that she’d offered during the night.

On the way out she bowed to the statue of Kwan Kung, God of War, and went down Mott Street holding back her tears.

White Face

Jack watched as the men in blue windbreakers shuttered every known gambling establishment on Mott, Bayard, and Pell Streets, including the mahjong rooms, massage parlors, and karaoke clubs.

The OCCB, Organized Crime Control Bureau, supported by state troopers, ATF agents, and U.S. Customs and Immigration officers, raided the Association headquarters of the On Yee, the Hip Ching, and the Fuk Chow.

While prominent white lawyers protested on the Associations’ behalf, the cops arrested every known Ghost on sight, and also hauled in the Dragons and Fuk Chings for good measure. The brazen gangboys were made to take the perp walk for the news reporters, ducking their heads to hide from the cameras, trying to avoid the humiliation of extreme loss of face.

The blue task force raided Chinatown apartments, basements, and warehouses for contraband goods: counterfeit designer handbags and computer software, watches, cassettes, and bootleg cigarettes. Department of Transportation marshals followed them and towed away all the gangsters’ muscle cars.

The 0-Five, backed by the outside layers of law enforcement, was sending a signal to all the tongs and gangbangers on Fifth Precinct turf, a hard-fisted notice that the NYPD blue gang was not going to tolerate the wanton violence that had brought embarrassment and critical scrutiny to their stationhouse.

The cops didn’t really give a shit if the gangsters killed each other, Jack knew, it was only politics. When the wind died down, the stench would return.

The pictures of seized contraband and the perp walks were published in the daily papers to show that the police had flexed their muscles, and were firmly in control of Chinatown.

One Police Plaza measured its comments, still wary of the fickle media.

Captain Marino called Jack and thanked him personally for his assistance, wishing him well on his return to the 0-Nine.

* * *

The United National, Chinatown’s oldest newspaper, ap-plauded the many Associations for their cooperation with law enforcement, for contributing to a safer neighborhood. Vincent Chin’s editorial pointed out the need for Chinese community-liaison officers, and more bilingual civilian employees in the local precincts.

The headlines in the New York Post announced NYPD MOVES TO END GANG VIOLENCE, CRACKS DOWN ON CHINATOWN TONGS.

The Daily News printed photos of the dead gangsters, labeling them “modern-day hatchetmen of the new tong wars.”

The Metro section of The Times printed a picture of Keung “Eddie” Ng, wanted as a person of interest by detectives of the Fifth Precinct.

Jack knew they meant Detectives Hernandez and Donelly.

BAI SAN, Paying Respect

January eighteenth was Pa’s birthday. Jack went to the cemetery alone, bringing the pair of potted hothouse Dusty Millers he’d bought at Fa Fa Florist. The cemetery grounds lay beneath a blanket of white, hard drifts that had piled up against the sides of the old mausoleums. The headstones were covered by white caps already melting in the morning sun, trickles of water running down toward the frozen earth.

From Pa’s gray headstone, Jack scanned the hushed ghostly scene. At the other side of the cemetery, on a hilly knoll that was part of the new Chinese section, he noticed a woman pulling items out of large shopping bags. She was a solitary figure in front of a new brown-colored headstone, setting down bright red pots of poinsettias, the only movement in the silent rolling expanse of white snow and evergreens.

Flames danced out of a big tin bucket as she fed the fire handfuls of gold– and silver-colored-paper taels, fake ancient Chinese money. A red cardboard car disappeared into the smoke, following the million-dollar packets of death money. Paper talismans of numerous Chinese gods were sacrificed, bot gwas in different colors and shapes.

Even in the distance, under the slanting sunlight, Jack could see she was crying as she spoke her prayers.

The sight made him feel even sadder.

He turned back to Pa’s patch of ground, placing his potted bushes gently into the snow on either side of Pa’s headstone. The dusty gray leaves with tiny white flowers accented the stone nicely. Touching his fingers to the Chinese words carved into the face of the stone, he searched his mind for good memories but could only recall that Pa had been a hardworking man, loyal to his friends.

He torched the incense and planted the thin sticks.

He bowed three times.

Wordlessly, he pulled the flask from his jacket and uncapped it. He poured out a thin stream of mao tai liquor that melted a line in the snow. Then he took a swig himself before resuming the final good-bye he hadn’t had the chance to say in life.

“Sorry, Dad,” he said quietly. “Hope you find some happiness up there.”

He emptied the flask and backed away from the headstone. Bowing again, he took a pack of firecrackers from his pocket, holding it while the sadness in his heart brought the tears to his eyes. He fired up his lighter, and slowly brought the flame to the skinny silver fuse.

The staccato bursts of the firecrackers were hammered by the boom of cherry bombs and the clanging of ash-can charges as the New Year’s crowds flooded into Chinatown.

The Year of the Pig had swept in on the icy wings of the hawk, and settled onto a left-over foot of snow and slush. Clouds of gray-blue smoke floated up from the fireworks as the masses tamped down the littered carpet of red particles that covered the winding snowy streets.

Jack smelled the stinging bite of sulfur and ash, tasted the gun powder in the cold air as lion dancers in colorful costumes leaped at the blazing explosions. They were inspired by the clash of gongs and cymbals, teasing the thundering war beat out of the big wooden drums, driving out the evil spirits that plagued Chinatowns everywhere.

The explosions blasted through the smoky air, spurring on the energetic lion dancers who were stomping through the snow to the pounding rhythm of the large drums. The plaintive gongs and raucous cymbals urged the crowds on, provoking another rain of fireworks.

The lion heads appeared to be breathing fire, bright white flashes of light beneath the brilliant gold, green, and red decorations that brightened the neighborhood. He saw images of golden pigs in all the shop windows.

Outside the Tofu King, Alexandra, wearing a quilted red meen nop jacket, stood beside Jack, soaking in the joyous outpouring as Mott Street filled with people and became impassable.

The kung-fu clubs performed all around them, twisting and thrusting the multicolored lion heads at the red envelopes offered by the shop owners.

Billy Bow, using a fat cigar for ignition, launched a mat of firecrackers into the street.

A long golden dragon, held high on poles, wound its serpentine way past them, followed by a pair of lunging silver unicorns.

Everywhere, a sea of bright red.

Twenty-foot strands of firecrackers, strung from fire escapes above, blazed to a thunderous end, inciting the crowds below to cheers and applause.

The New Year was a celebration of family bonds and a chance to embrace new beginnings. Wrap up loose ends, settle debts, clean the house, sweep out the dust, buy some new clothes.

The Pig was the twelfth sign, the last sign in the lunar cycle, the purest in heart and most generous of the animals. The Pig was loyal, chivalrous, and believed in miracles. The year was characterized by honesty, fortitude, and courage.

In Columbus Park, volunteers had shoveled back the snow, and the flower vendors pitched their colorful bouquets under the huge tent of the Lunar New Year flowers market.

The benevolent associations sponsored Chinese acrobats, and produced martial-arts demonstrations in their assembly halls. Because of the snow, there would be a shortened Lantern Parade accompanied by the Chinese School Marching Band.

The On Yee Association bankrolled a Cantonese Opera troupe’s performance at the Sun Sang theater, trumpeting a community alive with celebrations of tradition, culture, and family.

The NYPD had fenced off the main streets with metal barriers, and blocked out strategic areas for police vehicles. Crowd-control duties provided overtime cash for the uniforms, most of whom stuffed cotton wads into their ears, crinkled their noses, and held their breaths in the acrid smoke.

This celebration, this new Pig Year was foreign to them.

Jack spotted Jeff Lee in a crowd across the way on Pell, tossing firecrackers at a pair of bowing lion heads. Knowing that it was the monkey, Eddie Ng¸ who’d ripped off Jeff’s office on Pike, weighed on Jack’s mind.

Seeing Jeff reminded Jack that slick short Eddie was still at large. Jack had sent out bulletins to the various law enforcement agencies and was hopeful the ma lo hadn’t fled the country yet.

Jack tilted his face up to the blue sky and felt the warmth of the winter sun. Around him, the crowd roared again as more fireworks exploded, and Alexandra clutched his arm tightly against her body.

Sooner or later, he knew, Little Eddie’s trail would turn up.

Until then, the January sun felt good, and Alex was a comfort to him, making the possibilities of the new year seem open to fortitude, courage, and good fortune. . . .