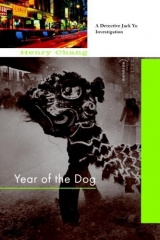

Текст книги "Year of the Dog "

Автор книги: Henry Chang

Жанры:

Прочие детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Takeout

“When the delivery came Jamal said, ‘Run the cash, ching chong.’ Then the Chinese kid went into his pocket and Jamal hit him in the back with the hammer. The kid threw the money to the floor. He started yelling and crying, trying to git away. Then Tyrone stabbed him and Jamal tossed a blanket over him, still beating him with the hammer. Tyrone kept stabbing into the blanket ’cause he kept moving, kicking his legs. Then Jamal grabbed the bat and hit him real hard on top and he went down. Jamal, mo times wit da bat. The kid was still crying but not so loud anymore. Tyrone finished him off with the hammer, ’til he didn’t move no more.”

DaShawn took a breath, was quiet a long moment. “I thought we wuz jes gonna rob him,” he said. “I know Jamal wanted money for sneakers, but I didn’t know Tyrone and him wuz gonna kill the guy. Swear to God, yo.”

Jack leaned back and caught the rest of DaShawn’s version.

“After, Jamal got mad. He was bitchin like ‘Damn. Chinee muthafucka only had fitty-one dollas.’ Tyrone was laughing, saying, ‘Shit, Nigga. No Air Jordons fo yo nigga ass!’ Jamal started cursing ‘Ah’ma have ta git two mo dese chinkees fo enough paper, yo.’ Tyrone said ‘So call in another takeout, nigga,’ but Jamal slapped him, said, ‘Everyone is closed now, fool.’ Then he was yelling, ‘Come on, clean dis shit up! Move dis ching-chong mofukka outta here before five-o comes down.’ Tyrone saying ‘Lookit all the blood. Red, too.’ He thought Chinee blood was yellow. They was laughing.”

Jack felt his hatred rise. They were all laughing, a hysterical joke, even as they wrapped the body, sponged up the blood. He stopped the tape recorder, made DaShawn scribble a statement implicating the other two.

“It was dem who done it. Tyrone and Jamal, they killd the Chinee kid.”

Jack took the signed statement and the tape, left the room, and went back to the detective’s area. Pasini waited there, grinning like he was impressed.

Jack reloaded the rap tape, readied the photographs. He gave Pasini a nod and headed for the holding cell where Tyrone was waiting to turn on his pals.

The Medical Examiner’s report had been delivered by one of the uniforms, who’d placed it in the wire basket on the detective’s table. It had Pasini’s name on it but Jack opened it anyway, took a long hard look.

Grisly morgue pictures of the teenager Hong’s body. Seen at different angles the body had thirteen stab wounds, from a knife blade eight inches in length, front and back, torso, stomach, shoulder, back, and arms, just everywhere. Some of the thrusts pierced his stomach and exited out of his lower back.

One stab had pierced his heart.

Six additional wounds to the head and shoulders, round quarter-size indentations about a half-inch deep. Blunt force impressions. One of the gangstas had swung the hammer like he was doing demolition work.

Metacarpus, phalanges. Broken fingers, both hands. Defensive wounds.

Fractured ulna, left forearm. Warding off the blows.

Fractured tibia, fibula, right side. A broken leg, dislocated kneecap. Kicked and hit going down.

Separated clavicle, the shoulder.

Three broken ribs on the left side. The bat.

An evidence photo of a Paul O’Neill Yankee Slugger, autographed model.

Shattered discs at the base of the spine, and higher, at the back of the neck. The bat, a swinging, killing club. Hitting home runs against Hong’s body flailing underneath the blanket.

The face has fourteen bones. In Hong’s face, twelve of these had been shattered. Mandible, palate, malar: jawbone, mouth, cheek. The black wood cracking through bone and gristle and teeth, crashing through nose and mouth.

A mutilated, destroyed face, then another photo showing a heavy metal Estwing, the claw hammer ripping out the nasus, the nose, the cartilage of septum, also the left eyeball (found in blanket). Facial structure crushed. Shattered occipital orbits, with skull fragments driven into the temporal areas. Displaced mastoid, and on and on, each notation consistent with a ball bat or hammer blow to the face.

Jack didn’t know if it was because of the side effects from the painkillers, but he felt sickened. He knew that this horror went on every day in this city, in America, in the world.

There were more than thirty incidences of blunt-force damage.

Jack took a breath, closed the report. In his head he was hearing grievous groaning and sobbing, the banshee wail welling up around the sad street of funeral parlors across from the playgrounds of his youth.

Death and Desperation

Koo Jai stepped away from Canal and went down Baxter, entering Chinatown the back way, through the park, and away from Mott Street where he’d risk running into Lefty. Or Kongo and the crazies crew. But he needed a sense of what was coming his way because he didn’t have what the dailo demanded. Fuck! That fuckin’ wristwatch and that stupid cunt were his downfall.

Coming around to Mulberry, in the distance, a funeral taking place. Fuck! He’d put together eight thousand, and of course the bunch of watches the dailo didn’t want. Fuck that, he wasn’t about to dump the Rolexes, Cartiers, and Rados, worth ten thousand at least, even if he was desperate. Fuck that. And none of the crew came up with any money, all full of excuses. They’d hoped to plead their case to the dailo, hoped that reason would prevail. Fuck them, too. He thought of Sai Go the bookie, whom he was now certain had complained to the dailo.

The funeral band started, warming up despite the cold day. Three brass trumpets and a trombone, and two drums, a snare and a bass. Pacing a slow walk to a sad dirge.

If he saw him at OTB, fuck Sai Go, too.

A few black-garbed relatives came outside to smoke cigarettes, the smell of incense billowing out behind them.

To avoid their bad karma following him, Koo Jai crossed away from the section of funeral parlors, and stayed to the park side, to where Worth led him around a bend to OTB, and later, back to East Broadway, anguishing, Right, where the fuck am I getting twelve thousand?

He thought momentarily of robbing the Fuk mahjong club but knew it would be heavily guarded during the holidays. fuckin’ hak, bad luck, he cursed. Black karma was following him.

* * *

Outside the Wah Fook funeral parlor, the drivers maneuvered their black Lincoln Town Cars for the day’s processions. Two trips in the morning, one in the afternoon. The Hong funeral, the smallest of the three, led off, a flower wagon trailing the dark hearse, ahead of four Lincolns and a minivan.

Earlier, the Fukien East Lions group had trekked down to the Alphabets and performed a lion dance in front of the New Chinatown takeout to drive away the evil spirits. One member set off a mat of firecrackers, the staccato blasts shooting forth bits of colored paper that settled on top of the frozen slush.

A squad car sat on the corner of Fifth Street, watching, but the uniforms refrained from citing the illegal fireworks ban.

At Alexandra’s suggestion, the Chinese Health Clinic had dispatched a team of Chinese-language grief counselors to the Hong home, an illegal basement rental in Sunset Park. The parents, who hadn’t slept in two days, were racked with grief, in stunned disbelief at their loss, their only son, their joy and their hope, the A-student who was going to be someone in Mai quo Fukienese America, gone, forever lost to brutal, senseless violence. Gone, their American dreams all gone. The murderers, hok-kwee black devils, teenagers too lazy or stupid to succeed in school, their brains dulled from drugs and alcohol, their hearts hardened by racism and hate, animal souls consumed by lust and violence.

The grief counselors were themselves stunned.

Sociopathic was a word not found in the Chinese language, an idea the parents could not comprehend. How could human beings have no regard for the evil they do? Unless, of course, they weren’t human beings but m’hai yun, a lower species of animal.

What could the grief counselors say? None of it made any sense.

In China, a criminal who committed murder would have received a Beijing haircut, a single nine-millimeter bullet to the head, followed by government’s bill to the executed person’s family for the price of the bullet.

In China, Jack knew, cops were liberal in their application of the law, justice there more pragmatic: do the crime, and you were executed. Simple as that, in a country with a billion people. There was no death row. There was no twenty years of appeals. China was six thousand years of civilization. They knew what worked. And they didn’t play.

He watched the funeral gathering from a distance, near the ball fields of his childhood.

The neighboring businesses on the street, from the undertaker at one end to the headstone cutter at the other, were all moved by the tragic death, and had contributed to the funeral, according to the Chinese press.

The Chin brothers’ Kingdom Caskets Inc. donated the simple bronze-colored coffin, a no-frills metal-veneer box.

Peaceful Florist discounted the floral wreaths, and the family’s village association paid for the funeral and the plot.

Several radio-car drivers had offered to drive the family for free to the cemetery in Brooklyn and back to Chinatown.

On the park side, a group of Buddhist monks from the Temple of Noble Truths concluded their prayer service and planted sticks of incense in the iron urn by the curb.

A group of Puerto Rican schoolgirls passed by and cracked jokes, goofing on the bald heads and saffron robes of the monks. Chino Viejo! Oh snap, like kong foo, their giggling cutting through the dirge.

Inside the Wah Fook parlor the air was thick, heavy with the pungent cloud of jasmine incense that cloaked the room. The overhead lights were dimmed to set off the glow of candles softly illuminating the gathering of grieving, sobbing faces.

A small gathering, barely twenty people.

Out by the main doorway, the reporters and photographers waited at a respectful distance. Jack walked by them and made his way to the incense urn, paying his respects by planting three sticks of incense and bowing. Stepping to the casket, he bowed again, turned, and came to offer condolences to the family before returning to the main door.

The reporters made notes in their pads, a sad end to another violent New York City story.

Another dead Chinese deliveryman.

There is enough anger here, Jack felt, in this small room. But where was the greater rage out there in the community? Would the Fukienese demonstrate again? Or would the old-guard Chinatown Cantonese make a statement?

No justice, no peace?

No just us, no please?

The community’s activist media would stay focused on this, Jack thought, and the DA’s office would be very aware of that. This one wasn’t going to be bargained away in some sealed juvie deal.

There was a freestanding black-and-white photograph of Hong, a smiling teenage face, just above the altar space. Below that was the closed casket the parents were forced to accept, so horrified were they by the damage to their son’s face.

A ring of flowers surrounded the closed coffin.

They could hear the band starting up across the street on the park side, a sad sweet “Nearer, My God, to Thee” in four-four time.

The pallbearers readying themselves to shoulder the load.

Suddenly, the mother uttered a harrowing cry, then exploded from her seat and threw herself across the coffin, knocking over her son’s framed photograph. The father and relatives rushed over to console and to restrain her. The mother was screaming, “Aah Jai! Ah Jai!!” and beating her chest, trying to tear her heart out, clutching at her hair. She fell to the floor, kicking, pounding the polished stone with her fists.

The relatives lifted her up, managed to slump her onto a seat, surrounding her from all sides supporting her, all of them wailing now, words useless in the whirlwind of grief.

The father stood speechless, ready to collapse.

The pallbearers lifted the casket, slowly beginning to walk toward the street. The band urged them on, the hearse standing at the curb with its tailgate open.

Up and down the street, drivers waited patiently as the pallbearers stepped slowly through the frozen morning, loading the coffin into the vehicle. The mother collapsed again and they carried her into one of the Town Cars. The band played until the last car moved off around the bend to Bayard, en route to the New Chinatown, then to Brooklyn, and on to everlasting sorrow.

Life Is Suffering

Sai Go sat in the barber chair and watched Bo in the mirror wall of the New Canton. She caught his glance and raised the chair, pumping the lever with her foot to position him.

“You look tanned,” she said with a smile. And tired, she thought. “Had a good time?”

“Yes,” answered Sai Go as she draped the plastic sheet over him, discreetly returning the clinic card and prescription note. “You left them here last time,” she said, grabbing a spray bottle.

Sai Go recognized the items immediately and nonchalantly pocketed them.

“Thanks,” he said. “And I’ve got something for you, too.” He produced a souvenir key ring with the Disney World logo, pleased by the happiness it brought to her face when he handed it to her.

“It’s got a light.” He smiled. “When you press the button.

For the dark places.”

“A wonderful gift.” She beamed, flashing the light. “Thank you much.” She remembered the talismans she had for him, but decided to wait until the end of the massage before showing them to him.

She misted his hair.

“The weather was good,” Sai Go said. “We went all over.”

Bo worked the little electric clipper against the long black comb.

“People swimming. People having fun,” he continued.

She misted again, and he squinted at the comb whipping around, chased by the buzz of the blades, hard salt-and-pepper clippings spraying across the plastic sheet.

“Everyone out in the sun,” he said, blinking.

“Just like a postcard,” Bo said, focused on the top of his head.

Sai Go felt himself floating, drifting behind his eyes. He scanned the overcast street in the mirrors, and felt detached, out of place. When he brought his focus back, he saw his quick trim, neat and tight. Bo was dusting his neck with powder, brushing him off. She loosened the plastic sheet.

He closed his eyes as Bo’s strong fingers kneaded the knots where the cords ran from his neck into his shoulders. He took a slow deep breath, released it the same way. He thought he’d felt something catching in his chest as she massaged his shoulders.

Inside his forehead he imagined palm trees and blue skies, the hot Florida sun on his face. Her thumbs dug into the base of his skull, rotated there, and then her forearms pressed and rubbed the sides of his neck.

He imagined a pack of greyhounds sprinting around a track, chasing a mechanical rabbit, and remembered he’d fallen asleep during the last race, but still came out a winner, a grand fifty dollars on the day.

Gum Sook’s herbal tea had made him feel good the first two days, then his energy faded and he became tired. He was sleepless the last days of the trip.

“When you get back, go to Sister Kee the herbalist,” recommended Gum Sook. “Put together litchi and seaweed. Boil garlic and chives with duck eggs. Mix in red wine and royal jelly. Eat and drink like a thick soup. For two days. I’ll write it down so she’ll know what to do.”

He’d appeared weak, and the two da jops, kitchen helpers, made sure he got home okay after they’d landed at LaGuardia. A see gay, radio car, returned them to Chinatown, and he’d slept most of the first day back. He woke up remembering his regular massage and haircut appointment, and the key ring.

Bo felt Sai Go sagging, drifting, with his eyes shut, to another place. She was sad to see how drained he looked, sensing that he was slowly dying. She chanted a Buddhist prayer in her head that never showed on her face as she drove her elbows into the clenched muscle behind his lungs, pushing the cancers back.

Sai Go opened his eyes as he started to nod off, jerking his head backward. Bo gave him a final squeeze and began drumming his back with her fists. When she was done, she presented him with the talisman Kwan Kung card and the jade gourd, slipping the red cord of the pendant over his head.

Sai Go was touched, not only by her healing hands, but by her generous compassion, which he didn’t understand, and didn’t feel he had the time to figure out. Here was a woman, working hard and saving every dollar to pay off the snakeheads so they wouldn’t turn her into a whore, and yet she presented him with new talismans, trinkets he’d seen for sale on Chinatown streets that had probably set her back twenty dollars. Cheap enough, but it was the thought, he reminded himself.

“Thank you,” he said meekly. “But you shouldn’t have,” aware of the precariousness of her financial situation. He gave her the usual tip, but when he tried to pass her an extra twenty, she became hock hee, indignant, about accepting payment from him.

It was not Sai Go’s style to force it upon her.

“It’s only a small gift,” she said firmly. “Why won’t you let me enjoy giving something to you?”

He had nothing to say to that.

“How about this,” he suggested. “I’ll bet the twenty on a horse for you. It’ll be like Lotto, okay?”

Offered a chance to test her luck, she couldn’t refuse. A small smile broke through and she said, “If you like.”

“Good then,” he said, relieved. “I’ll bring you the ticket.”

At the OTB, Sai Go reviewed the list of entries and settled on the eighth horse in the eighth race, an eight-to-one underdog. Sai Go watched the odds changing across the board, the smart money running to the number five and number two horses, driving their odds down. The number eight horse looked even better to him then.

The teller at the window was confused when he saw the resident bookie purchase a legitimate ticket. He noticed Sai Go’s sickly pallor and thought better of making a wisecrack.

Sai Go paid quickly and avoided any players who were looking for action. On the street he bought a small silk jewelry purse. It cost a dollar and he chose a red one for luck, red with gold embroidery. He tucked the OTB ticket inside and zipped it up.

He returned to the New Canton and gave it to Bo, saying, “Look for the race on the deen see, TV, or check the papers. You have the number eight horse, named American Freedom. I hope it’s lucky for you.”

Bo ran her fingers over the red silk, holding the purse as if it was precious, and said, “Thank you,” so softly it seemed she was whispering to herself. She watched him go back out into the street, slowly crossing in the direction of Chatham Square, a tanned face against a dingy gray background of storefronts.

At the far corner, he paused and glanced back, and for an instant she believed she saw a smile on his face.

Space for Time

The world below was a cloudy gray drift of mountain ranges and valleys with the occasional appearance of roads, a small city or village. He’d passed this way many times before, he remembered, flying west from Toronto, where he’d broken in the first credit-card crews, to Vancouver, where the Red Circle was a top player in spite of the authorities.

Now, seated comfortably on Air Canada Flight 688, Gee Sin was cruising at twenty thousand feet, descending toward Vancouver, for a two-night layover before the long flight back to Hong Kong. He saw the Canadian coastline below and took a deep breath, as if a weight had been removed. He was already out, out of the United States, out of American airspace, out of its legal jurisdiction. Out of sight and out of mind.

He would not be present for any investigation into the shootings over the bus routes, or the bad blood between the Fukienese crews, or the feuding tongs. The Red Circle’s financial involvement would be on hold until the Fukienese side cleaned up its own house.

The attention that the shootings brought was disappointing. Best to postpone for now.

Credit-card operations in the numerous cities would proceed as scheduled.

While descending, Sin considered the Chinatown murder of Uncle Four, and decided that the matter of the stolen gold pandas and diamonds would be given to Grass Sandal. He would be instructed to arrange a meeting with the Chinatown limousine driver whom the New York City police had in custody. The incarcerated driver could provide details and clues leading to the missing mistress.

Best to do it from Hong Kong, he thought, where he had vastly more control of matters.

One of the triad’s law firms could start the necessary legal machinery needed to obtain the interview from there.

Otherwise, the holiday had been going well. A handful of shoppers had been arrested, as expected, but the majority were bringing in significant sums. Besides, shoppers could be recruited everywhere; they were expendable.

The volume from the phone and mail-order houses surpassed even his expectations. Grass Sandal had had to close or vacate several receiving locations because they’d filled up with electronic swag after they had been used for a number of weeks. Millions of dollars worth of laptops, camcorders, game systems, cameras, computer software were consolidated for reshipment, then passed through the fences, stores they had arrangements with. The goods were converted to cash and became counterfeit Gucci and Prada bags in Hong Kong, hills of bak fun, white powder in Cambodia, then changed to currency again in Europe, Canada, America.

Cheat the people all around.

The strategy of the triad was paying off.