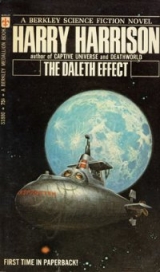

Текст книги "The Daleth Effect"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

9

The table was littered with magazines and booklets that did not interest Horst Schmidt. Novy Mir, Russia Today, Pravda, Twelve Years of U.S. Imperialist Intervention and Aggression in Laos. He leaned back in the chair, resting his elbow on the journals, and drew deeply on his cigarette. A pigeon flapped and landed on the windowsill outside, turning a pink eye to look at him through the water-beaded pane. He tapped the cigarette on the edge of the ashtray and, at the sudden motion inside the room, the pigeon flew away. Schmidt turned as the door opened and Lidia Efimovna Shirochenka came into the room. She was a slim, blond-haired girl, who might have appeared Scandinavian had it not been for her high Slavic cheekbones. Her green tweed suit was well cut and fashionable, undoubtedly purchased in Denmark. Schmidt saw that she was reading his report, frowning over it.

“There is precious little here of any value,” she said curtly, “considering the amount of money we pay you.” She sat down behind the desk that bore a small plaque reading Troisieme Secretaire de la Legation. She spoke in German, utilizing this opportunity, as a good party member, to a dual advantage; gaining linguistic practice with a native speaker.

“There is a good deal of information there. Intelligence, even negative information, is still intelligence. We now know that the Americans are as much in the dark as we are about the affair at Langeliniekaj. We know that their fair-weather allies the Danes are not acquainting their NATO comrades with all of their internal secrets. We know that all of the armed forces seemed to be involved. And if you will carefully note the last paragraph, tovarich Shiro-chenka, you will see that I have tentatively identified one of the civilians who was aboard the Isbjorn during the same day when there was all that excitement. He is Professor Rasmussen, a Nobel prize winner in physics, which I find most interesting. What is the connection between this affair and a physicist?”

Lidia Shirochenka seemed unimpressed by this disclosure. She took a photograph from a drawer and passed it over to Schmidt. “Is that the man you are talking about?”

He had too many years of experience at guarding his expression to reveal any reaction—but he was very surprised. It was a very grainy picture, obviously taken with a telescopic lens under poor light conditions, yet good enough to be instantly recognizable. Ove Rasmussen, carrying a small case, was walking down a ramp from a ship.

“Yes, that’s the same man. Where did you get this?”

“That is none of your business. You must realize that you are not the only man in the employ of this department. Your physicist now appears to be connected in some manner with rockets or missiles. Find out all you can about him. Who he sees, what he is doing. And do not tell the Americans about this littie bit of information. That would be most unwise.”

“You insult me! You know where my loyalty lies.”

“Yes. With yourself. It is impossible to insult a double agent. I am just attempting to make it clear that it would be a drastic mistake for you to betray us in the same manner that you have betrayed your CIA employers. There is no loyalty for you, just money.”

“On the contrary, I am most loyal.” He snubbed out his cigarette, then took out his package and offered one to Li-dia Shirochenka. She raised her eyes slightly at the label American cigarettes were very expensive in Copenhagen. “Have one. I get them at PX discount, about a fifth of the usual price.” He waited until he had lighted her cigarette before he continued.

“I am most loyal to your organization because it is the wisest arrangement for me. Speaking as a professional now, I can assure you that it is very difficult to got reliable intelligence information about the U.S.S.R. You have rigorous security procedures. Therefore I am tiappy for the items—I presume they are false—that you supply me for the Americans. They will never discover this because the CIA is hideously inefficient and has a one hundred percent record of never having ever been correct with intelligence information supplied to their own government. But they pay very well indeed for what they receive from me, and there are many fringe benefits.” He held up his cigarette and smiled. “Not the least of which is the money you pay me for revealing their little secrets. I find it a profitable arrangement. Besides, I like your organization. Ever since Beria…”

“Things have changed a great deal since Beria,” she said sharply. “A former SS man like yourself, an Oberst at Auschwitz has little claim to moral arguments.” When he did not answer she turned to look out of the window, at the long white building barely visible through the light rainfall. She pointed.

“There they are, Schmidt, just across the graveyard from us. There is something very symbolic in that, have you never thought?”

“Never,” he said emotionlessly. “You have far more insight into these matters than I have, tovarich Shirochenka.”

“Don’t ever forget that. You are an employee whom we watch very closely. Try to get closer to this Professor Rasmussen…”

She broke off as the door opened. A young man in his shirtsleeves hurried in and handed her a piece of paper that had been torn from the teleprinter. She scanned it quickly and her eyes widened.

“Boshemoi!” she whispered, shocked. “It can’t be true.”

The young man wordlessly nodded his head, the same look of numb disbelief on his face.

* * *

“How many hours now?” Arnie asked.

Ove looked at the chart hanging on the laboratory table. “Over two hundred fifty—and that is continuous operation. We seem to have most of the bugs worked out.”

“I hope to say you do.” Arnie admired the shining, cylindrical apparatus that almost filled the large work-stand. It was festooned with wires and electronic plumbing, and flanked by a large control board. There was no sound of operation other than a low and distant humming. “This is quite a breakthrough,” he added.

“The British did most of the groundwork back in the late sixties. I was interested because it related to some of my own work. I had been able to build up plasmas of two thousan‹ degrees, but only for limited amounts of time, a few thoi sand microseconds. Then these people at Newcastle on Tyne began using a helium-caesium plasma at fourteen hundred sixty degrees centigrade with an internal electric field. They were increasing the plasma conductivity up to a hundred times. I utilized their technique to build Little Hans here. I haven’t been able to scale up the effect yet, not practically, but I think I see a way out. In any case Little Hans works fine and produces a few thousand volts steadily, so I cannot complain.”

“You have done wonders.” Arnie nodded thanks as one of the laboratory assistants handed him a cup of coffee. He stirred it slowly, thinking. “Scaled up this could be the power source we need for a true space vessel. A pressurized atomic generator, of the type now used in submarines and surface craft, would fit our needs. No fuel needed, no oxidant. But with one inherent drawback.”

“Cooling,” Ove said, and blew on his hot coffee.

“Exactly. You can cool with sea water in a ship, but that sort of thing is hard to come by in space. I suppose an external radiating unit could be constructed…”

“It would be far bigger than the ship itself!”

“Yes, I imagine it would. Which brings us back to your fusion generator. Plenty of power, not too much waste heat to bleed off. Will you let me help you with this?”

“Delighted. Between us I know…” He broke off, distracted by a sudden buzz of conversation from the far end of the laboratory. “Is there anything wrong down there?”

“I’m very sorry, Professor, it is just the news.” She held up an early edition of BT.

“What’s happened?”

“It’s the Russians, that Moon-orbiting flight of theirs. It has turned out to be more than that, more than just a flight around the Moon. It is a landing capsule, and they have set it down right in the middle of the Sea of Tranquility.”

“The Americans won’t be overjoyed about this,” Ove said. “Up until now they have considered the Moon a bit of American landscape.”

“That’s the trouble.” She held the newspaper out to them, I19: eyes wide. “They have landed, but something is wrong with their lunar module. They can’t take off again.”

There was little more to the newspaper report, other than the photograph of the three smiling cosmonauts that had been taken just before take-off. Nartov, Shavkun, and Zlotnikova. A colonel, a major, and a captain, in a neatly organized chain of command. Everything had been very well organized. Television coverage, reporters, take-off, first stage, second stage, radioed reports and thanks to Comrade Lenin for making the voyage possible, the approach, and the landing. They were down on the Moon’s surface and they were alive. But something had gone wrong. What had happened was not clear from the reports, but the result was obvious enough. The men were down. Trapped. There for good. They would live just as long as their oxygen lasted.

“What an awful way to die, so faf from home,” the laboratory assistant said, speaking for all of them.

Amie thought, thought slowly and considered what had happened. His eyes went to the fusion generator, and when he looked back he found that Ove had been looking at it too, as though they both shared the same idea.

“Come on,” Ove said, looking at his watch. “Let’s go home. There’s nothing more to be done here today, and if we leave now we can beat most of the traffic.”

Neither of them talked as Ove pulled the car through the stream of bicycles and turned north on Lyngbyvej. They had the radio on and listened to the news most of the way to Charlottenlund.

“You two are home early,” Ulla said when they came in. She was Ove’s wife, a still attractive redhead, although she was in her mid-forties. While Arnie was staying with them she had more than a slight tendency to mother him, thinking he was far too thin. She took instant advantage of this unexpected opportunity. “I’m just making tea and I’ll bring you in some. And some sandwiches to hold you until dinner.” She ignored all protests and hurried out.

They went into the living room and switched on the television. The Danish channel had not come on the air yet, but Sweden was broadcasting a special program about the cosmonauts and they listened closely to this. Details were being released, almost grudgingly, by Moscow, and the entire tragedy could now be pieced together.

The landing had been a good one right up to the very end. Setdown had been accomplished in the exact area that had been selected and, until the moment of touchdown, it had looked perfect. But as the engines cut off one of the tripod landing legs had given way. Details were not given, whether the leg itself had broken or gone into a hole, but the results were clear enough. The lunar module had fallen over on its side. One of the engines had been torn free: an undisclosed quantity of fuel had been lost. The module would not be able to take off. The cosmonauts were down to stay.

“I wonder if the Soviets have a backup rocket that could get there?” Arnie asked.

“I doubt it. They would have mentioned it if there were any chance. You heard those deep Slavic tones of tragedy in the interview. If there were any hope at all it would have been mentioned. They are already written off, and busts are being made of them for the Hall of Fame.”

“What about the Americans?”

“If they could do anything they would jump at the chance, but they have said nothing. Even if they had a ship ready to go, which they probably don’t, they don’t have a window. This is the completely wrong time of the month for them to attempt a lunar trip. By the time there is a window that trio of cosmonauts will be dead.”

“Then… nothing can be done?”

“Here’s your tea,” Ulla said, bringing in the heavily loaded tray.

“You know better than that,” Ove told him. “You have been thinking the same thing I have. Why don’t we take the fusion generator, put it in Blaeksprutten—and go up there to the Moon and rescue them.”

“It sounds an absolutely insane idea when you come right out and say it.”

“It’s an insane world we live in. Shall we give it a try—see if we can talk the Minister into it?”

“Why not?” Arnie raised his cup. “To the Moon, then.”

“To the Moon!”

Ulla, eyes wide, looked back and forth from one to the other as though she thought they were both mad.

10

The Moon

“Signing off until sixteen hundred hours foir next contact,” Colonel Nartov said, and threw the switch on the radio. He wore sunglasses and ragged-bottom shorts, hacked from his nylon shipsuit, and nothing else. His dark whiskers were now long enough to feel soft when he rubbed kt them, having finally grown out of the scratchy stage. They itched too: not for the first time he wished that there was enough water to have a good scrub. He felt hot and sticky all over, and the tiny cabin reeked like a bear pit.

Shavkun was asleep, breathing hoarsely through his gaping mouth. Captain Zlotnikova was fiddling with the knobs on the receiver—they had more than enough power from their solar panels—looking for the special program that was beamed to them night and day. There was static, a blare of music, then the gentle melody of a balalaika playing an old folk melody. Zlotnikova leaned back, arms behind his head, and hummed a quiet accompaniment. Nartov looked up at the blue and white mottled globe in the black sky and felt a strong desire for a cigarette. Shavkun groaned in his sleep and made smacking noises with his mouth.

“Chess?” Nartov asked, and Zlotnikova laid down the well-worn thin-paper copy of The Collected Works of V.I. Lenin that he had been leafing through. It was the only book aboard—they had planned to read from it when they planted the Soviet flag in Lunar soil—and, while inspiring in other circumstances, bore little relationship to their present condition. Chess was better. The litde pocket set was the most important piece of equipment aboard Vostok IV.

“I’m four games ahead of you,” Nartov said, passing over the board. “You’re white.”

Zlotnikova nodded and played a safe and sane pawn to king four. The colonel was a strong player and he was taking no chances. The sun, pouring down on the Sea of Tranquility outside, hung apparently motionless in the black sky, although it crept closer to the horizon all the time. Even with sunglasses he squinted against the glare, automatically looking for some movement, some change in that ocean of rock and sand, mother-of-pearl, grayish green, lifeless.

“Your move.” He looked back at the board, moved his knight.

“A vacuum, airless… whoever thought it would be this hot?” Zlotnikova said.

“Whoever thought we would be here this long, as I have told you before. As highly polished as this ship is, some radiation still gets through. It hasn’t a hundred percent albedo. So we warm up. We were supposed to be here less than a day, it wasn’t considered important.”

“It is after eleven days. Guard your queen.”

The colonel wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his arm, looked out at the changeless moonscape, looked back to the board. Shavkun grunted and opened his eyes.

“Too damn hot to sleep,” he mumbled.

“That hasn’t seemed to bother you the last couple of hours,” Zlotnikova said, then castled queenside to get away from the swiftly mounting kingside attack. “Watch your tongue, Captain,” Shavkun said, irritable after the heat-sodden sleep. “I’m a Hero of the Soviet People,” Zlotnikova answered, unimpressed by the reprimand. Rank meant very little now.

Shavkun looked distastefully at the other two, heads bent over the board. He was a really second-rate player himself. The other two beat him so easily that it had been decided to leave him out of the contest. This gave him too much time to think in.

“How long before the oxygen runs out?”

Nartov shrugged, bearlike and fatalistic, without bothering to look up from the board. “Two days, maybe a third. We’ll know better when we have to crack the last cylinder.”

“And then what?”

“And then we will decide about it,” he said with quick irritation. Playing the game had put the unavoidable from his mind for a few minutes; he did not enjoy being dragged back to it. “We have already talked about it. Dying by asphyxiation can be painful. There are a lot simpler ways. We’ll discuss it then.”

Shavkun slid from the bunk and leaned against the viewport, which was canted at a slight angle. They had managed to level off the vessel by digging at the other two legs, but nothing could replace the lost fuel. And there was the Earth, looking so close. He pulled the camera from its clip and squinted through the pentaprism, using their strongest telescopic lens.

“That storm is over. The entire Baltic is clear. I do believe I can even see Leningrad. It’s clear, really clear there with the sun shining…”

“Shut up,” Colonel Nartov said sharply, and he did.

11

The gray waters of the Baltic hissed along the side of the MS Vitus Bering, breaking into mats of foam that were swept quickly astern. A seagull flapped slowly alongside, an optimistic eye open for any garbage that might be thrown overboard. Arnie stood at the rail, welcoming the sharp morning air after the night in the musty cabin. The sky, still banded with red in the east where the sun was pushing its edge over the horizon, was almost cloudless, its pale blue bowl resting on the heaving plain of the sea. The door creaked open and Nils came on deck, yawning and stretching. He cocked a professional eye out from under the brim of his uniform cap—his Air Force one, not SAS this time—and looked around.

“Looks like good flying weather, Professor Klein.”

“Arnie, if you please, Captain Hansen. As shipmates on this important flight I feel there should be less formality.”

“Nils. You’re right, of course. And, by God, it is important, I’m just beginning to realize that. All the planning is one thing, but the thought that we are leaving for the Moon after breakfast and will be there before lunch… It’s a little hard to accept.” The mention of food reminded him of the vacant space in his great frame. “Come on, let’s get some of that breakfast before it’s all gone.”

There was more than enough left. Hot cereal and cold cereal; Nils had a little of each, sprinkling the uncooked oatmeal over his cornflakes and drowning them both in milk in the Scandinavian manner. This was followed by boiled eggs, four kinds of bread, a platter of cheese, ham, and salami. For those with even better appetites there were three kinds of herring. Arnie, more used to the light Israeli breakfast, settled for some dark bread and butter and a cup of coffee. He looked with fascinated interest as the big pilot had one serving of everything to try it out, then went around again for seconds. Ove came in, poured some coffee, and joined them at the table.

“The three of us are the crew,” he said. “It’s all set. I was up half the night with Admiral Sander-Lange and he finally saw the point”

“What is the point?” Nils asked, talking around a large mouthful of herring and buttered rugbrad. “I’m a pilot, so you must have me, but is there any reason to have two high-powered physicists aboard?”

“No real reason,” Ove answered, ready with the answer after a night of debating the point. “But there are two completely separate devices aboard—the Daleth drive and the fusion generator—and each requires constant skilled attention. It just so happens that we are the only two people for the job, sort of high-paid mechanics, and that is what is important. The physicist part is secondary at this point. If Blaeksprutten is to fly, we are the only ones who can fly her. We’ve come so far now that we can’t turn back. Our risk is really negligible—compared to the certain death facing those cosmonauts on the Moon. And it’s also a matter of honor now. We know we can do it. We have to try.”

“Danish honor,? Nils said gravely, then broke into a wide grin. “This is really going to rock the Russians back on their heels! How many people in their country? Two hundred twenty-six or two hundred twenty-seven million, too many to count. And how many in all of Denmark?”

“Under five million.”

“Correct—a lot less than in Moscow alone. So they have all their parades and rockets and boosters and speeches and politicians, and their thing falls over and all die juice runs out. So we come along and pick up the pieces!”

The ship’s officers at the next table had been silent, listening as Nils’s voice grew louder with enthusiasm. Now they burst out in applause, laughing aloud. This flight appealed to the Danish sense of humor. Small they were, but immensely proud, with a long and fascinating history going back a thousand years. And, like all the Baltic countries, they were always aware of the Soviet Union just across that small, shallow sea. This rescue attempt would be remembered for a long time to come. Ove looked at his watch and stood up.

“It is less than two hours to our first lift-off computation. Let us see if we can make it.”

They finished quickly and hurried on deck. The submarine was already out of the hold and in the water, with technicians aboard making the last-minute arrangements.

“With all these changes the tub really needs a new name,” Nils said. “Maybe Den Flyvende Blaeksprutte—the Flying Squid. It has a nice ring to it.”

Henning Wilhelmsen climbed back over the rail and joined them, his face set in lines of unalloyed glumness. Since he knew her best, he had supervised all of the equipment changes and installations.

“I don’t know what she is now—a spaceship I guess. But she’s no longer a sub. No power plant, no drive units. I had to pull out the engine to make room for that big tin can with all the plumbing. And I even bored holes in the pressure hull!” This last crime was the end of the world to any submariner. Nils clapped him on the back.

“Cheer up—you’ve done your part. You have changed her from a humble larva into a butterfly of the skies.”

“Very poetical.” Henning refused to be cheered up. “She’s more of a luna moth than a butterfly now. Take good care of her.”

“You can be sure of that,” Nils said, sincerely. “It’s my own skin that I’m worried about, and Den Flyvende Blaeksprutte is the only transportation around. All changes finished?”

“All done. You have an air-pressure altimeter now, as well as a radio altimeter. Extra oxygen tanks, air-scrubbing equipment, a bigger external aerial, everything they asked for and more. We even put lunch aboard for you, and the admiral donated a bottle of snaps. Ready to go.” He reached out and shook the pilot’s hand. “Good luck.”

“See you later tonight.”

There was much handshaking then, last-minute instructions, and a rousing cheer as they went aboard and closed the hatch. A Danish flag had been painted on the conning tower and it gleamed brightly in the early morning sun.

“Dogged tight,” Nils said, giving an extra twist to the wheel that sealed the hatch above, set into the conning tower’s deck.

“What about the hatch on top of the tower?” Ove asked.

“Closed but not sealed, as you said. The air will bleed out of the conning tower long before we get there.”

“Fine. That’s about as close to an airlock as we can rig on a short notice. Now, are we all certain that we know what to do and how to do it?”

“I know,” Nils grumbled, “but I miss the checklists.”

“The Wright brothers didn’t have checklists. We’ll save that for those who follow after. Arnie, can we run through the drill once more?”

“Yes, of course. We have a computation coming up in about twenty minutes, and I see no reason why we should not make it.” He went forward to look out of a port. “The ship is moving away to give us plenty of room.” He pointed down at the controls in front of Nils, most of them newly mounted on top of the panel.

“Nils, you are the pilot I have rigged controls here for you that will enable you to change course. We have gone over them so you know how they operate. We will have to work together on take-offs and landings, because those will have to be done from the Daleth unit, which I will man. Ove is our engine room and will see to it that we have a continuous supply of current. The batteries are still here, and charged, but they will be saved for emergencies. Which I sincerely hope we will not have. I will make the vertical take-off and get us clear of the atmosphere. Nils will put us on our course and keep us on it. I will control acceleration. If the university computer that ties in with the radar operates all right, they should tell us when to reverse thrust. If they do not tell us, we shall have to reverse by chronometer and do the best we can by ourselves.”

“Now that is the part I don’t understand,” Nils said, pushing his cap back on his head and pointing to the periscope. “This is a plain old underwater periscope—now modified so that it looks straight up rather than ahead. It had a cross hair in it. Fm supposed to get a star in the cross hair and keep it there, and you want me to believe that this is all we have to navigate by? Shouldn’t there be a navigator?”

“An astrogator, if you want to be precise.”

“An astrogator then. Someone who can plot a course for us?”

“Someone whom you can have a little more faith in than a periscope you mean?” Ove asked, laughing, and opened the door to the engine compartment.

“Exactly. I’m thinking about all those course corrections, computations, and such that the Americans and Soviets have done before to get to the Moon. Can we really do it with this?”

“We have the same computations behind us, realize that. But we have a much simpler means of applying them because of the shorter duration of our flight. When time is allowed for our initial slower speed through the atmosphere, our flying time is almost exactly four hours. Knowing this, certain prominent stars were picked as targets and the computations were made. Those are our computation times. If we leave at the correct moment and keep the target star in the sight all of the time, we will be aiming at the spot in the Moon’s orbit where it will be at the end of the four hours. We both move to our appointed meeting place, and the descent can be made. After we locate the Soviet capsule, that is.”

“And that is going to be easy?” Nils asked, looking dubious.

“I don’t see why not,” Ove answered, poking his head out of the engine cubby, wiping his hands on a rag. “The generator is operating and the output is right on the button.” He pointed to the large photograph of the Moon pasted to the front bulkhead. “Goodness, we know what the Moon looks like, we’ve all looked through telescopes and can find the Sea of Tranquility. We go there, to the right spot, and if we don’t see the Soviets we use the direction finder to track them down.”

“And at what spot do we look in the Sea of Tranquility? Do we follow this?” Nils pointed to the blurry photograph of the Moon that had been cut from the newspaper Pravda.› There was a red star printed in the north of the mare where the cosmonauts had landed. “Pravda says this is where they are. Do we navigate from a newspaper photo?”

“We do unless you can think of something better,” Arnie said mildly. “And do not forget our direction finder is a standard small boat model bought from A.P. Moller Ship Supplies in Copenhagen. Does that bother you too?”

After one last scowl Nils burst out laughing. “The whole thing is so outrageous that it just has to succeed.” He fastened his lap belt. “Blaeksprutten to the rescue!”

“It is all much more secure than it might look,” Ove explained. “You must remember that we had this operational submarine to begin with. It is a sealed, tested, proven, self-sufficient spaceship built for a different kind of space. But it works just as well in a vacuum as under water. And the Daleth drive is operational and reliable—and will get us to the Moon in a few hours. The combination of radar and computer on Earth will track us and compute the correct course for us to follow. Everything possible has been done to make this trip a safe one. There will be later voyages and the instrumentation will be refined, but we have all we need now to get us safely to the Moon afld back. So don’t worry.”

“Who is worrying?” Nils said. “I always sweat and get pale at this time of day. Is it time to leave yet?”

“A few more minutes to go,” Arnie said, looking at the electronic chronometer before him. “I am going to take off and get a bit of altitude.”

His fingers moved across the controls and the deck pressed up against them. The waves dropped away. Tiny figures were visible aboard the Vitus Bering, waving enthusiastically, then they shrank and vanished from sight as Blaeksprutten hurled itself, faster and faster, into the sky.

The strangest thing about the voyage was its utter uneventfulness. Once clear of the atmosphere they accelerated at a constant one G. And one gravity of acceleration cannot be sensed as being different in any way from the gravity experienced on the surface of the Earth. Behind them, like a toy, or the projection on a large-size screen, the globe of the Earth shrank away. There was no thunder of rockets or roar of engines, no bouncing or air pockets. Since the ship was completely sealed, there was not even the small drop in atmospheric pressure that is felt in a commercial airliner. The equipment worked perfectly and, once clear of the Earth’s atmospheric envelope, their speed increased.

“On course—or at least we are aimed at the target star,” Nils said. “I think we can check with Copenhagen now and see if they are tracking us. It would be nice to know if we are going in the right direction.” He switched the transceiver to the preset frequency and called in the agreed code.

“Kylling calling Halvabe. Can you read me? Over.” He threw the switch. “I wonder what drunk thought up these code names,” he mumbled to himself. The sub was the “chick” and the other station the “lemur”—but these names were also slang terms for a quarter-litre and a hali-litre bottle of akvavit.