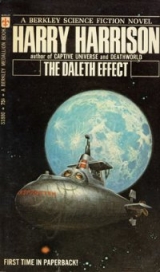

Текст книги "The Daleth Effect"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Harry Harrison

The Daleth Effect

1

Tel-Aviv

The explosion that blew out the west wall of the Physics Laboratory of the University of Tel-Aviv did little real harm to Professor Arnie Klein who was working there at the time. A solid steel workbench protected him from the blast and flying debris, though he was knocked down and cut his cheek as he fell. He was understandably shaken as he climbed to his feet again, blinking at the blood on his fingertips where he had touched his face. The far side of the laboratory was just rubble and twisted wreckage, with wreaths of dust or smoke curling up from it.

Fire! The thought of this stirred him to motion. The apparatus had been destroyed, but his records of the experiment and his notes might still be saved. He tugged wildly at the drawer, bent and warped by the blast, until it squealed open. There it was, a thin file folder, a few weeks work—but how important. Next to it a worn folder, fifteen centimeters thick, six years of concentrated labor. He pulled them both out, and since the opening in the wall was close at hand, he went out that way. His records must be made secure first; that was the most important thing.

The pathway here at the back of the building was seldom used, and was deserted now in the breathless heat of the afternoon. This was a shortcut that had been physically impossible to reach from the laboratory before, but now led directly to the faculty dormitory close by. The file would be safe in his room—that was a very good idea. He hurried there, as fast as one can hurry when the dry, furnace-like wind of the khamsin is blowing. Because he was already deep in thought he did not realize that his movements were completely unobserved.

Arnie Klein appealed slow-witted to many people, but this was only because he was constitutionally unable to follow more than one train of thought at a time, and he had to chew this thought out with methodical thoroughness until every drop of nourishment had been extracted. His mind worked with meticulous precision and ground incredibly fine. Only this unique ability had kept him firmly on this line of reasoning for six years, a complicated chain of mathematical supposition based only upon a gravimetric anomaly and a possible ambiguity in one of Einstein’s basic field theory equations.

Now his mind was occupied with a new train of speculation, one he had considered before, but which the explosion had now proven to be a strong possibility. As usual, when deeply involved in thought, his body performed routine operations with, in truth, his conscious mind being completely unaware of them. His clothing was dusty from climbing the debris, as were his handstand there was blood on his face. He stripped and automatically took a shower, cleaned the cut and applied a small bandage. Only when he began to dress again did his conscious mind intervene. Instead of putting on clean shorts, he took the trousers of his lightweight suit from their hanger and slipped them on. He put a tie in the jacket pocket and draped the jacket across a chair. After this he stopped, in silence for some minutes, while he worked out the logical conclusions of this new idea. A neat, gray-haired man in his early fifties, looking very ordinary, if one made allowance for the fact that he stood for ten minutes, unblinking and motionless, until he reached that conclusion.

Arnie was not sure yet what would be the wisest thing, but he knew what the alternative possibilities were. Therefore he opened his attaché case, still on the dresser where he had put it upon his return from the Belfast Physical Congress the previous week, that contained a book of Thomas Cook Sons traveler’s checks. It was very full because he had thought he would have to pay for his airplane tickets and be reimbursed, but instead the tickets had arrived prepaid. Into the attaché case he put the file folder and his passport, with its visas still in effect; nothing else. Then, with his jacket folded neatly over his arm and carrying the attaché case, he went down the stairs and walked toward the waterfront. Less than a minute later two excited students ran, sweating and breathless, up to his room and hammered on the door.

The khamsin blew with unobstructed relentlessness once he was away from the protection of the campus buildings, drawing the moisture from his body. At first Ar-nie did not notice this but, in Dizengoff Road, passing the cafés, he became aware of the dryness in his mouth and he turned into the nearest doorway. It was the Casit, a bohemian, Left Bank sort of place, and no one in the variegated crowd even noticed him as he sat at a small table and sipped his gazos.

It was there thafhis chain of thought unreeled to its full length and he made up his mind. In doing this he was completely unaware of any outside influences, and had no idea that an alarmed search was being carried out for him, that waves of consternation were spreading out from the epicenter of the university. At first it had been thought that he was buried under the debris caused by the mysterious explosion, but rapid digging disproved that idea. Then it was discovered that he had been in his room; his soiled clothing was found, as well as traces of blood. No one knew what to believe. Had he been hurt and was he wandering in shock? Had he been abducted? The search widened, though it certainly never came near the Casit café. Inside, Arnie Klein stood up, carefully counted out enough prutot coins to pay for his drink, and left.

Once again luck was on his side. A taxi was letting out a fare at Rowal’s, the sophisticated café next door, and Arnie climbed in while the door was still open.

“Lydda Airport,” he said, and listened patiently while the driver explained that he was going off duty, that he would need more petrol, then commented unfavorably on the weather and a few other items as well The negotiations that followed were swift because, now that he had come to a decision, Arnie realized that speed would avoid a great deal of unpleasantness.

As they started toward the Jerusalem road two police cars passed them, going in the opposite direction at a tremendous pace.

2

Copenhagen

The hostess had to tap his arm to get his attention.

“Sir, would you please fasten your seat belt. We’ll be landing in a few minutes.”

“Yes, of course,” Arnie said, fumbling for the buckle. He saw now that the seat belt and no smoking signs were both lit.

The flight had passed very quickly for him. He had vague memories of being served dinner, although he could not remember what it was. Ever since taking off from Lydda Airport he had been absorbed in computations that grew out of that last and vital experiment. The time had passed very swiftly for him.

With slow grandeur, the big 707 jet tipped up on one wing in a stately turn and the Moon moved like a beacon across the sky. The clouds below were illuminated like a solid yet strangely unreal landscape. The airliner dropped, sped above the nebulous surface for a short time, then plunged into it. Raindrops traced changing pathways across the outside of the window. Denmark, dark and wet, was somewhere down below. Arnie saw that his notebook, the open page covered with scribbled equations, was on the table before him. He put it into his breast pocket and closed the table. Points of light appeared suddenly through the rain and the dark waters of the Oresund streamed by beneath them. A moment later the runway appeared and they were safely down in Kastrup Airport.

Arnie waited patiently until the other passengers had shuffled by. They were Danes for the most part, returning from sunshine holidays, sunreddened faces glowing as though about to explode. They clutched straw sacks and Oriental souvenirs—wooden camels, brass plates, exfoliating rugs—and each had the minuscule tax-free bottle of alcoholic spirits that their watchful government permitted them to bring in. Arnie went last, paces behind the others. The cockpit door was open as he passed, revealing a dim hutch incredibly jammed with shining dials and switches. The captain, a big blond man with an awe-inspiring jaw, smiled at him as he passed. Capt. Nils Hansen the badge above his gold wings read.

“I hope you enjoyed the flight,” he said in English, the international language of the airways.

“Yes indeed, thank you. Very much.” Arnie had a rich British-public-school accent, entirely out of keeping with his appearance. But he had spent the war years at school in England, at Winchester, and his speech was marked for life.

All of the other passengers were queued up at the customs booths, passports ready. Arnie almost joined them until he remembered that his ticket was written through to Belfast and that he had no Danish visa. He turned down the glass-walled corridor to the transit lounge and sat on one of the black leather and chrome benches while he thought, his attaché case between his legs. Staring unseeing into space he considered his next steps. In a few minutes he had reached a decision, and he blinked and looked about. A police officer was tromping solidly through the lounge, massive in his high leather boots and wide cap. Arnie approached him, his eyes almost on a level with the other’s silver badge.

“I would like to see the chief security officer here, if you would.”

The officer looked down, frowning professionally.

“If you will tell me what the matter is…”

“Dette kommer kun mig og den vagthavende officer ved. Så må jeg tale med han?”

The sudden, rapid Danish startled the officer.

“Are you Danish?” he asked.

“It does not matter what my nationality is,” Arnie continued in Danish. “I can tell you only that this is a matter of national security and the wisest thing for you to do now would be to pass me over to the man who is responsible for these matters.”

The officer tended to agree. There was something about the matter-of-factness of the little man’s words that rang of the truth.

“Come with me then,” he said, and silently led the way along a narrow balcony high above the main airport hall, keeping a careful eye open so that the stranger with him made no attempt to escape to the rain-drenched freedom of the Kastrup night.

“Please sit down,” the security officer said when the policeman had explained the circumstances. He remained seated behind his desk while he listened to the policeman, his eyes, examining Arnie as though memorizing his description, staring unblinkingly through round-paned, steel-framed glasses.

“Lojtnant Jorgensen” he said when the door had closed and they were alone.

“Arnie Klein.”

“Må jeg se Deres pass?”

Arnie handed over his passport and Jorgensen looked up, startled, when he saw it was not Danish.

“You are an Israeli then. When you spoke I assumed…” When Arnie didn’t answer the officer flipped through the passport, then spread it open on the bare desk before him.

“Everything seems to be in order, Professor. What can I do for you?”

“I wish to enter the country. Now.”

“That is not possible. You are here in transit only. You have no visa. I suggest you continue to your destination and see the Danish Consul in Belfast. A visa will take one day, two at the most.”

“I wish to enter the country now, that is why I am talking to you. Will you kindly arrange it. I was born in Copenhagen. I grew up no more than ten miles from here. There should be no problem.”

“I am sure there won’t be.” He handed back the passport. “But there is nothing that can be done here, now. In Belfast…”

“You do not seem to understand.” Arnie’s voice was as impassive as his face, yet the words seemed charged with meaning. “It is imperative that I enter the country now, tonight. You must arrange something. Call your superiors. There is the question of dual nationality. I am as much a Dane as you are.”

“Perhaps.” There was an edge of exasperation to the lieutenant’s voice now. “But I am not an Israeli citizen and you are. I am afraid you must board the next plane.”

His words trickled off into silence as he realized that the other was not listening. Arnie had placed his attaché case on his knees and snapped it open. He took out a thin address book and flipped carefully through it.

“I do not wish to be melodramatic, but my presence here can be said to be of national importance. Will you therefore place a call to this number and ask for Professor Ove Rude Rasmussen. You have heard of him?”

“Of course, who hasn’t? A Nobel prize winner. But you cannot disturb him at this hour…”

“We are old friends. He will not mind. And the circumstance is serious enough.”

It was after one in the morning and Rasmussen growled at the phone like a bear woken from hibernation.

“Who is that? What’s the meaning… Sa for Satan!… is that really you, Arnie. Where the devil are you calling from? Kastrup?” Then he listened quietly to a brief outline of the circumstances.

“Will you help me then?” Arnie asked.

“Of course! Though I don’t know what I can possibly do. Just hold on, I’ll be there as soon as I can pull some clothes on.”

It took almost forty-five minutes and Jorgensen felt uncomfortable at the silence, at Arnie Klein staring, unseeing, at the calendar on the wall. The security officer made a big thing of snapping open a package of tobacco, of filling his pipe and lighting it. If Arnie noticed this he gave no sign. He had other things to think about. The security officer almost sighed with relief when there was a quick knocking on the door.

“Arnie—it really is you!”

Rasmussen was like his pictures in the newspapers; a lean, gangling man, his face framed by a light, curling beard, without a moustache. They shook hands strongly, almost embracing, smiles mirrored on each other’s faces.

“Now tell me what you are doing here, and why you dragged me out of bed on such a filthy night?”

“It will have to be done in private.”

“Of course.” Ove looked around, noticing the officer for the first time. “Where can we talk? Someplace secure?”

“You can use this office if you wish. I can guarantee its security.” They nodded agreement, neither seemingly aware of the sarcastic edge to his words.

Thrown out of his own office—what the hell was going on? The lieutenant stood in the hall, puffing angrily on his pipe and tamping the coal down with his calloused thumb, until the door was flung open ten minutes later. Rasmussen stood there, his collar open and a look of excitement in his eyes. “Come in, come in!” he said, and almost pulled the security officer into the room, barely able to wait until the door was closed again.

“We must see the Prime Minister at once!” Before the astonished man could answer he contradicted himself. “No, that’s no good. Not at this time of night.” He began to pace, clenching and unclenching his hands behind his back. “Tomorrow will do for that. We have to first gU you out of here and over to my house.” He stopped and stared at the security officer.

“Who is your superior?”

“Inspector Anders Krarup but—”

“I don’t know him, no good. Wait, your department, the Minister…”

“Herr Andresen.”

“Of course—Svend Andresen—you remember him, Ar-nie?”

Klein considered, then shook his head no.

“Tiny Anders, he must be well over six feet tall. He was in the upper form when we were at Krebs’ Skole. The one who fell through the ice on the Sortedamso.”

“I never finished the term. That was when I went to England.”

“Of course, the bastard Nazis. But hell remember you, and he’ll take my word for the importance of the matter. We’ll have you out of here in an hour, and then a glass of snaps into you and you into bed.”

It was a good deal more than an hour, and it took a visit by a not-too-happy Minister Andresen, and a hurriedly roused aide, before the matter was arranged. The small office was filled with big men, and the smell of damp wool and cigar smoke, before the last paper was stamped and signed. Then Lieutenant Jorgensen was finally alone, feeling tired and more than a little puzzled by the night’s events, his head still filled with the Minister’s grumbled advice to him, after taking him aside for a moment.

“Just forget the whole thing, that’s all you have to do. You have never heard of Professor Klein and to your knowledge he did not enter the country. That is what you will say no matter who asks you.”

Who indeed? What was all the excitement about?

3

“I really don’t want to see them,” Arnie said. He stood by the high window looking out at the park next to the university. The oak trees were beginning to change color already; fall came early to Denmark. Still, there was an excitement to the scene with the gold leaves and dark trunks against the pale northern sky. Small puffs of white clouds moved with stately grace over the red-tiled roofs of the city; students hurried along the paths to classes.

“It would make things easier for everyone if you would,” Ove Rasmussen said. He sat behind his big professor’s desk in his book-lined professor’s office, his framed degrees and awards like heraldic flags on the wall behind him. Now he leaned back in his deep leather chair, turned sideways to watch his friend by the window.

“Is it that important?” Arnie asked, turning about, hands jammed deep into the pockets of the white laboratory coat. There were smears of grease on the sleeve and a brown-rimmed hole in the cuff where a soldering iron had burned through.

“I’m afraid it is. Your Israeli associates are very anxious to find out what happened to you. I understand they traced your movements through a cab driver. They have discovered that you flew by SAS to Belfast—but that you never arrived there. Since the only stopover was here in Copenhagen it was rather hard to conceal your whereabouts. Though I hear that the airport people did give them a very hard time for a while.”

“That Lieutenant Jorgensen must have earned his salary.”

“He did indeed. He was so bullheaded that there was almost an international incident before the Minister of State admitted that you were here. Now they insist upon talking to you.”

“Why? I am a free man. I can go where I please.”

“Tell them that. Dark hints about kidnapping have been dropped…”

“What! Do they think that the Danes are Arabs or something like that?”

Ove laughed and twisted about in his chair as Arnie stamped over and stood before the desk.

“No, nothing like that,” he said. “They know—unofficially of course—that you came here voluntarily and that you are unharmed. But they are very curious as to why you have come here, and they are not going to go away until they have some answers. There is an official commission right now in the Royal Hotel. They say they will make a statement to the press if they don’t see you.”

“I do not want that to happen,” Arnie said, worried now.

“None of us does. Which is why they want you to meet the Israelis and tell them that you are doing fine and they can take the next flight out. You don’t have to tell them any more than that.”

“I do not want to tell them any more than that. Who have they sent?”

“Four people, but I think three of them are just yes men. I was with them most of the morning, and the only one who really mattered was a General Gev…”

“Good God! Not him.”

“You know him?”

“Entirely too well. And he knows me. I would rather talk to anyone else.”

“I’m afraid you’re not getting that chance. Gev is outside right now waiting to see you. If he doesn’t talk to you he says he is going straight to the press.”

“You can believe him. He learned his fighting in the desert. The best defense is a good offense. You had better show him in here and get it over with. But don’t leave me alone with him for more than fifteen minutes. Any more than that and you may find that he has talked me into going back with him.”

“I doubt that.” Ove stood and pointed to his chair. “Sit here and keep the desk between you. It gives one a feeling of power. Then he’ll have to sit on my student-chair there, which is hard as flint.”

“If it were a cactus he would not mind,” Arnie said, depressed. “You do not know him the way I do.”

There was silence after the door closed. An occasional shout from the students outside penetrated the double glass window, but only faintly. Inside the room the ticking of the tall Bornholm clock could be clearly heard. Arnie stared, unseeing, at. his folded hands on the desk before him and wondered what to do about Gev. He had to tell him as little as possible.

“It’s a long distance to Tel-Aviv,” a voice said in guttural Hebrew and Arnie looked up, blinking, to see that Gev was already inside the room and had closed the door behind him. He was in civilian clothes but wore them, straight-backed, like a uniform. His face was tanned, lined, dark as walnut: the long scar that cut down his cheek from his forehead pulled the corner of his mouth into a perpetual half-grin.

“Come in, Avri, come in. Sit down.”

Gev ignored the invitation, stamping across the room, on parade, to stand over Arnie, scowling down at him as though he had been inspected and found wanting.

“I’ve come to take you home, Arnie. You are one of our leading scientists and your country needs you.”

There was no vacillation, no appeal to Arnie’s emotions, to his friends or relations. General Gev had issued an order, in the same voice that had commanded the tanks, the jets, the soldiers into combat. He was to be obeyed. Arnie almost rose from his chair and followed him out, so positive was the command. Yet he only stirred uncomfortably in the chair. His decision had been made and nothing could be done about it.

“I am sorry, Avri. I am here and I am going to stay here.”

Gev stood, glowering down on him, his arms at his sides but his fingers curved, as though ready to reach out and grasp and pull Arnie bodily to his feet. Then, in instant decision, he turned and sat down in the waiting chair and crossed his legs. His frontal assault had been repulsed; he turned the flank and prepared to attack in a more vulnerable area. Never taking his eyes from Arnie he took a vulgarly large gold cigarette case from his pocket and snapped it open. The flag of the United Arab Republic was set into the case in enamel, the two green stars picked out with emeralds. A bullet hole punched neatly through the case.

“There was an explosion in your laboratory,” Gev said. “We were concerned. At first we thought you were dead, then injured—then kidnapped. Your friends have been very concerned…”

“I did not mean them to be.”

“…and not only your friends, your government. You are an Israeli, and the work you do is for Israel. A file is missing. Your work has been stolen from your country.”

Gev lighted a cigarette and drew deeply on it, cupping the burning end in his hand, automatically, the way a soldier does. His eyes never left Arnie’s face and his own face was as expressionless as a mask, with only those accusing eyes peering through. Arnie opened his hands wide in a futile gesture, then clasped them before him once again.

“The work has not been stolen. It is my work and I took it with me when I left. When I left voluntarily, to come here. I am sorry that you… think ill of me. But I did what I had to do.”

“What was this work?” The question was cold and sharp, and cut deep.

“It was… my work.” Arnie felt outmaneuvered, outfought, and could only retreat into silence.

“Come now, Arnie. That’s not quite good enough. You are a physicist and your work has to do with physics. You had no explosives, yet you managed to blow up some thousands of pounds worth of equipment. What have you invented?”

The silence lengthened, and Arnie could only stare miserably at his clenched hands, his knuckles whitening with the pressure. Gev’s words pulled at him, relentlessly.

“What is this silence? You can’t be afraid? You have nothing to fear from Eretz Israel, your homeland. Your friends, your work, your very life is there. You buried your wife there. Tell us what is wrong and we will help you. Come to us and we will aid you.”

Arnie’s words fell like cold stones into the silence.

“I… cannot.”

“You have to. You have no other choice. You are an Israeli and your work is Israeli. We are surrounded by an ocean of enemies and every man, every scrap of material is vital for our existence. You have discovered something powerful, something that will aid our survival. Would you remove it and see us all perish—the cities and the synagogues leveled to be a desert again? Is that what you want?”

“You know that I do not! Gev, let me be, get out of here and go back…”

“That I won’t do. I won’t let you be. If I am the voice of your conscience, so be it. Come home. We will welcome you. Help us as we helped you.”

“No! That is the thing I cannot do!” The words were pulled from his body, a gasp of pain. He went on quickly, as though the dam to his feelings had been broken and he could not stop.

“I have discovered something—I will not tell you how, why, what it is—a force. Call it a force, something that is perhaps more powerful, or could be more powerful than anything we know today. A force that can be used for good or evil because it is by nature that sort of thing, if I can develop it, and I think I can. I want it used for good—”

“Israel is evil! You dare suggest that?”

“No, hear me out, I did not say that. I mean only that Israel is the pawn of the world with no one on their side.

Oil. The Arabs have the oil, and the Soviets and the Americans want it and will play any dirty game to get it. No one cares for Israel, except the Arabs who wish to see her destroyed, and the world powers who also wish they could find a way to destroy her quietly, the thorn in their sides. Oil. War will come, something will happen, and if you have my—if you had this, what we are talking about, it would be used for destruction. You would use it, with tears in your eyes perhaps, but you would use it—and that would be absolute evil.”

“Then,” General Gev said, in a voice so low it was scarcely audible, “from pride, personal ambition, you will withhold this force and see your country perish? In your supreme egocentricity you think yourself more fit to make major policy decisions than the elected representatives of the people. You place yourself on a pillar. You are unique. Better able to decide the important issues than all the lesser mortals of the world. You must believe in absolute tyranny—your tyranny. In your arrogance you become a little Hitler…”

“Shut up!” Arnie shouted hoarsely, half rising from the chair. There was silence. He sat down again, slowly, aware that his face was flushed, a pulse hammering like a rivet gun in his temple. It took a great effort to speak calmly.

“All right. You are correct in what you say. If you wish to say that I no longer believe in democracy, say it. In this matter I don’t. I have made the decision and the responsibility is mine alone. To myself, perhaps as an excuse, I prefer to think of it as a humane act…”

“Mercy killing is also humane,” Gev said in a toneless voice.

“You are right, of course. I have no excuses. I have acted willfully and I accept the responsibility.”

“Even if Israel is destroyed through your arrogance?”

Arnie opened his mouth to answer, but there were no words. What could be said? Gev had him hemmed in from all sides, his retreat was cut off, his defenses destroyed. What could he do other than surrender? All that remained was the persistent conviction that, in the long run, he was doing the right thing. A conviction that he was afraid to test or examine lest it prove false as well. The silence grew and grew and a great sadness pushed down on Arnie so that he slumped in his chair.

“I do what I have to do!” he said, finally, in a voice hoarse with emotion. “I will not return. I have left Israel as I came, voluntarily. You have no hold on me, Gev, no hold…”

General Gev stood up, looking down upon the bowed head. His words were slow in coming and when he did speak, there was the echo of three thousand years of persecution, of death, of mourning, of a great, great sadness.

“You, a Jew, you could do this… ?”

There was no possible answer and Arnie remained silent. Gev was soldier enough to see defeat even though he could not understand it. He turned his back, he said nothing more, though what more could be said than this act of turning his back and leaving? He pushed the door open with his fingertips and did not touch it again, to close it or even slam it, but went straight out. Upright, marching, a man who had lost a battle, but who would never lose a war without dying first.

* * *

Ove came in and puttered around the room, stacking the magazines, pulling out a book then putting it back unopened, doing this for some minutes in silence. When he finally spoke it was about something else.

“Listen, what a day it is out. The sun’s shining, you can see for miles. You can see the girls’ skirts blowing up when they ride their bicycles. I’ve had enough of this filthy caféteria food, I’m stuffed solid right up to here with rugbrod. I can’t face another sandwich. Let’s go to Langelinie Pavillonen for lunch. Watch the ships sail by. What do you say?”

There was a stricken look on Arnie’s face when he raised his head. He was not a man normally given to strong emotions of any kind, and he had no defenses, no way of dealing with what he now felt. There was the pain—written so clearly on his face that Ove had to turn away and push about the magazines so recently ordered.

“Yes, if you want to. We could have lunch out.” His voice was as empty of emotion as his face was lined with it.

They drove in silence down Norre Alle and through the park. It was indeed as Ove had said. The girls were on their high black bikes, flashes of color among the drab jackets of the men, pacing the car on the bicycle paths that bordered the wide street, sweeping in ordered rows across the intersections. Their long legs pumped and their skirts rode up freely and it was a lovely afternoon. Except that Arnie carried with him the memory of a great unhappiness. Ove twisted the little Sprite neatly through the converging traffic at Trianglen and down Osterbrogade to the waterfront. The car shot through a gap in the Langelinie traffic and braked under the rear of the Pavillonen restaurant. They were early enough to get a table at the great glass window that formed one wall. Ove beckoned to the waiter and ordered before they sat down. Even as they were pulling up their chairs a bottle of akvavit appeared, frozen in a block of ice, and a brace of frosted bottles of Tuborg Fine Festival beer.