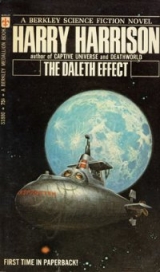

Текст книги "The Daleth Effect"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

17

Moon Base

“I really cannot do it,” Arnie said. “There are a number of other people who can do the job just as well, far better in fact. Professor Rasmussen here, for one. He knows everything about the work.”

Ove Rasmussen shook his head. “I would if I could, Arnie. But you are the only one who can say what must i said. In fact I’m the one who suggested that you speak.”

Arnie was surprised at this, and his eyes almost accuse Ove of betrayal. But he said nothing about it. He turner instead to the efficient young man from the Ministry c State who had come to the Moon to arrange all the detail?

“I have never spoken on television before,” Arnie told him. “Nor am I equipped to lie in public.”

“No one would ever ask you to lie, Professor Klein/ the efficient young man said, snapping open his attach case and slipping out a folder. “We are asking you to tell only the truth. Someone else will discuss the situation here, tell all the details, and not he at all. The most that will be said—or not said—will be an error of omission. The work here at Manebasen is not completely finished. and it is no grave crime to suggest that it is. This ship L part of the base now, there are depots outside for the equipment, and construction continues right around the clock.”

“He’s right,” Ove said quietly. “The situation is getting worse all the time in Denmark. There was an attack on the atomic institute last night. A car full of men dressed like police. They broke in, shot it out with the troops when they were discovered. Fourteen dead in all.”

“Like Israel—the terror raids,” Arnie said, mostly to himself, his eyes mirroring a long-remembered pain.

“Not the same at all,” Ove insisted quickly. “You can’t hold yourself to blame at all for anything that has happened. But you can help stop any further trouble, you realize that?”

Arnie nodded, silently, looking out of the lounge window. The pitted lunar plain stretched away from the ship, but the view of most of the sky was cut off by the sharply rising lip of a large crater. Closer in, a large yellow diesel tractor was digging an immense gouge in the soil, its blue cloud of exhaust vanishing into the vacuum at almost the same instant it appeared. A nest of six large oxygen cylinders was strapped behind the driver.

“Yes, I will do it,” Arnie said, and once the decision had been made he dismissed it from his mind. He pointed the tractor driver, who was dressed in a black and How suit with a bubble helmet.

“Any more troubles with suit leaks?” he asked as the ate Ministry man hurried out.

“Little ones, but we watch and keep them patched.We’re keeping the suit pressure at five pounds, so there is o real trouble. We should be happy we could get pressure suits at all. I don’t know what we would have done if we adn’t been able to buy these from the British, surplus from their scotched space program. Once things are set—led the Americans and the Soviets will be falling over sach other to supply us with suits for—what is the expression?”

“A piece of the action.”

“Right. We’ll soon have this base dug in and completely roofed over, and we’ll convert everything to electrical operation so we won’t have to keep bringing oxygen cylinders from Earth.”

He broke off as the television crews wheeled in their equipment. Lights and cameras were quickly mounted, the microphone cords spread across the floor. The director, a busy man with a pointed beard and dark glasses, shouted instructions continually.

“Could I ask you boys to move,” he said to Ove and Arnie, and waved the prop men toward their chairs. The furniture was shoved aside and rearranged, a long table moved over, while the director framed the scene in his hands.

“I want that window off to one side, the speakers below it, mikes on the table, get a carafe of water and some glasses, find something for that blank hunk of wall.” He spun on his heel and pointed “There. That picture of the Moon. Move it over here.”

“It’s bolted down,” someone complained.

“Well unbolt it! That’s what you have fat fingers and a little tool kit for.” He ran back and looked through the viewer on the camera.

Leif Holm stamped into the room, large as life, wear the same ancient-cut suit that he had worn in his office Helsingor.

“Some flight I had in that little Blaeksprutten” he said shaking hands firmly with the two physicists. “If I was Catholic I would have been crossing myself all the way. Couldn’t even smoke. Nils was afraid I would clog up the air equipment or something.” Reminding himself of h forced abstinence, he took his large cigar case from an inner pocket.

“Is Nils here now?” Arnie asked.

“He took off right away,” Ove told him. “They’re using the ship for a television relay and he is holding position above the horizon.”

“Back of the Moon, that’s the way,” Leif Holm said, clipping off the end of his immense cigar with a cutter hung from his watch chain. “So they can’t watch us with their damned great telescopes.”

“I haven’t had a chance to congratulate you yet,” Ove said.

“Very kind, thank you. Minister for Space. It has a good sound to it. I also don’t have to worry what my predecessors did—since I don’t have any.”

“If you will please take your places we can have the briefing now,” the State Ministry man said, hurrying in. He was beginning to sweat. Arnie and Leif Holm sat behind the table, and someone went running for an ashtray. “Here are the main points we want to mention.” He laid the stapled sheets in front of both of them. “I know you have been briefed, but these will be of help in any case. Minister Holm, you will make your opening statements. Then the journalists on Earth will ask questions. The technical ones will be answered by Professor Klein.”

“Who are the journalists?” Arnie asked. “From what countries?”

“Top people. A tough crowd. The Soviets and Americans, of course, and the major European countries. The other countries have been pooled and have elected ir own representatives. There are about twenty-five in.

“Israeli?”

“Yes. They insisted on having a representative of their m. All things considered, you know, we agreed.”

“The link is open,” the director called out “Stand by. Three minutes. We are tied into Eurovision, by satellite to le Americas and Asia. Top viewing. Just watch the monitor and you will know when you are on.”

A television set with a large screen was placed under camera one. The picture was adequate, the scene tense. [Tie Danish announcer was finishing the introduction, in English, the language that would be used for this broadcast.

“…from all over the world, gathered here in Copenhagen today, to talk to them on the Moon. It must be remembered that it takes radio waves nearly two seconds to reach the Moon, and the same amount of time to return, so there will be this amount of time between question and reply during the latter half of this session. We will now switch you over to the Danish Moon Station, to Mr. Leif Holm, the Minister for Space.”

The red light glowed on camera two, and they appeared on the monitor screen. Leif Holm carefully tapped his ash into the ashtray and inhaled from his cigar, so that his first words were accompanied by a generous cloud of smoke.

“I am speaking from the Moon, where Denmark has established a base for research and commercial development of the Daleth drive that has permitted these flights. The construction is in its earliest stages—you can see the operation continuing behind me through the window—and will continue until there is a small city here. For the beginning this base will be dedicated to scientific research, to continue the development of the Daleth drive that has made this all possible. In one sense this portion of the work is already completed because all”—he leaned forward to stare grimly at the camera—“all of the Daleth project is now at this base. Professor Klein, sitting on my right, is here to direct the research. He has brought assistants with him, all of his equipment, records, even thing to do with this project.” He leaned back and dr‹ on his cigar again before continuing.

“You will excuse my insistence on this fact, but I wii to make it clear. Denmark in the past months has suffers many acts of violence within her borders. Crimes ha been committed. People have been killed. It is sad to admit, but there are national powers on Earth that will go to any lengths to obtain information about the Daleth drive. I speak to them now, and I beg forgiveness in advance from all of the peace-loving countries of the world, the overwhelming majority. You can stop now. Leave. There is nothing for you to steal. We in Denmark intend to develop the Daleth effect for the greater benefit of mankind. Not for violence.”

He stopped, almost glaring at the screen, then leaned back. Arnie was staring straight ahead, expressionless, as he had done during the entire talk.

“We will now answer any specific questions that you may have.”

The scene on the monitor changed to the auditorium in Copenhagen where the press representatives waited. They sat on chairs, in neat rows, in attitudes of silent attention, while slow seconds slipped by. It was disconcerting to realize that radio waves, even at the speed of light, took measurable seconds to cross the great distance between the Moon and Earth. In an abrupt, galvanic change the scene altered as a number of the newsmen jumped to their feet, clamoring for attention. One of them was recognized and the cameras focused on him, a burly man with a great shock of hair. The white letters UNITED STATES OF AMERICA appeared below him on the screen.

“Can you tell us who is making these alleged attacks in Denmark? These so called ‘national powers,’ to use your own term, in the plural, could, by inference, mean any country. Therefore all the countries stand condemned by innuendo. This is highly unfair.” He glowered at the camera.

‘I am sorry that you find it so,” Holm responded ally. “But it’s the truth. Attacks have occurred. People have died. It is unimportant to go into the question further. Surely the world press must have more relevant questions in this one.”

Before the angry reporter could answer, another man was recognized, the representative of the Soviet Union who, if he was also angry, managed to conceal it very ell.

“Of course the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ins in with all the peace-loving nations of the world to condemn the acts of aggression that have occurred in Denmark.” He exchanged a look of mutual hatred with the American reporter, then went on. “A more important question would be, What does your country intend to do with this Daleth drive?”

“We intend to exploit it commercially,” Holm answered after the mandatory seconds had passed. “In the same way that Danish shipping opened up the commercial possibilities of East Asia during the last century. A company has been formed, Det Forenede Rumskibsselskab, The United Spaceship Company, a partnership between the government and private industry. We mean to open up the Moon and the planets. At this time there are of course no specific plans, but we are sure that great opportunities lie ahead. Raw materials, research, tourism—who knows where it will end? We in Denmark are most enthusiastic, because at this time we see no end to the good that will come from it.”

“Good for Denmark,” the Russian said before another questioner could be recognized. “Does not this monopoly mean that you will deprive the rest of the world of fair share in the venture? Should you not, as a socialist country, share your discovery in the true socialist spirit?”

Leif Holm nodded solemn agreement. “Though many of our public institutions are socialistic, enough of our private ones are sufficiently capitalistic to keep us from giving away what you have called a ‘monopoly.’ It is a monopoly only in the sense that we shall operate the Daleth ships, at a fair profit, that will open up the so system to all the countries of the Earth. We will try not be greedy. We have already entered into an agreement with other Scandinavian countries for the manufacture of the ships. Our belief is that this invention will benefit all mankind, and we consider it our duty to implement this belief.”

The representative of the Israeli press was recognized from the crowd of excited, waving men, and he addressed the camera. He had a detached, scholarly manner, with a tendency to look over the top of his rimless glasses, but Arnie recognized him as one of the shrewdest commentators that country had.

“If this discovery is of such a great benefit to mankind, I would like to ask why it has not been made available to the entire world? My question is directed to Professor Klein.”

Arnie had short seconds to prepare his answer—but he had been expecting the question. He looked directly into the camera and spoke slowly and clearly.

“The Daleth effect is more than a means of propulsion. It could be turned to destructive uses with ease. A country with the will to conquer the world could conquer the world through utilization of this effect. Or destroy the world in the attempt.”

“Could you elaborate? I am anxious to discover how this species of rocket ship engine could do all you say.”

He smiled, but Arnie knew better than to believe the smile. They both knew more about the history of the Daleth effect than they were admitting aloud.

“It can do more because it is not a kind of rocket engine. It is a new principle. It can be applied to lift a small ship—or a large ship. Or even an entire concrete-and-steel fortress mounting the heaviest cannon, and to take this anywhere in the world in a matter of minutes. It could hang in space, on top of the gravity well, immune from any retaliation by rockets, even atom-bomb-equipped rockets, and could destroy any target it wished with bombs or shells. Or if that image is not horrific enough for you, the Daleth effect could be made to pick up sat boulders—or even small mountains—from here on e Moon, and drop them on Earth. There is no limit to e imaginable destruction.”

“And you feel that the other countries of the world would use the Daleth effect for destruction if they had it?” he other reporters were silent for the moment, recognizing the underplay in the dialogue between the two men.

“You know they would,” Arnie snapped back. “Since when has the horrible potential of a weapon stopped it from being used? The cultures who have practiced genocide, used poison gas and atom bombs in warfare, will stop at nothing.”

“And you felt that Israel would do these things? Since I understand you first developed the Daleth effect in Israel and took it from this country.”

Arnie had been expecting this, but he still wilted visibly beneath the blow. When he spoke again his voice was so low that the engineers had to turn up the volume of their transmission.

“I did not wish to see Israel forced to choose between her survival and the unleashing of great evil upon the world. At first I considered destroying my papers, until I realized that there was a very good chance that someone else might reach the same conclusions and make the same discovery that I did. I was forced to come to a decision—and I did.” He was angry now, defiant in his words.

“To the best of my knowledge I did the right thing, and I would do it over again if I were forced to. I brought my discovery to Denmark because, as much as I love Israel, it is a country at war, that might eventually be forced to use the Daleth effect for war. It was my belief that if I found a way for my work to benefit all mankind, Israel would benefit too. Benefit first, for all that I owe her. But Denmark—I know this country, I was born there—could never be tempted into war by aggression. This is the country that twice almost voted unilateral disarmament for itself. In a world of tigers they wished to go unarmed! They have faith. I have faith in them. I could be wrong but, God save me, I have done the best I could…”

His voice choked with emotion, and he looked aw from the camera. The director instantly switched the see; back to Earth. After the moments of waiting an Indian reporter was recognized, the representative of an Asiatic reporter pool.

“Would the Minister of Space be so kind as to elaborate upon the benefits to accrue from the utilization of this discovery and to suggest, if possible, what specific benefit there might be for the countries of southern Asia?”

“I can do that,” Holm said, and looked down at his cigar, surprised to see that he had completely forgotten it, and that it had gone out.

18

Rungsted Kyst

“It’s a perfect day for it,” Martha Hansen said, rubbing out the cigarette in the ashtray, then clasping her hands together to conceal how excited she was.

“It certainly is, it certainly is,” Skou said, his nose pushed forward, looking around as though sniffing out trouble. “Will you excuse me for a moment?”

He was gone before Martha could answer, with his two shadows trailing after him. She shook another cigarette out of the pack and lighted it; at this rate she would have a pack smoked before noon. She twisted about, with her legs up on the couch, smoothing down her skirt. Had she worn the right thing? The knitted dress was always Nils’s favorite. How long had it been? She turned quickly when she heard a car—but it was only the traffic passing on Strandvejen. The sun burned down on a scene of green grass, tall trees, and the bright blue waters of the Sound beyond. White sails leaned away from the wind and a bee-buzzing motorboat drew a pale line of wake toward Sweden. A June Sunday with the sun shining—Denmark would be heaven, and Nils was coming home! How many months…

It was practically a convoy, three large black cars, pulling into the drive and stopping before the house. A police car and another car parked at the curb beyond them. They were here. She ran, getting there ahead of Skou, throwing the door wide.

“Martha!” he shouted, dropping his bag and sweeping her to him, kissing her so hard she had no breath, right there on the porch. She managed to push free, laughing, when she realized that a small circle of men was waiting patiently for them to finish.

“I’m sorry, please come in,” she said, aware that her hair was mussed and her lipstick probably smeared, and not giving a damn. “Arnie, it is wonderful to see you. Come in please.” Then they were in the living room, just the three of them, with the sound of heavy feet stamping through the rest of the house.

“Fm sorry about the honor guard,” Nils said. “But it was the only way we could get Arnie back to Earth for a holiday. It was time for us all to have a break, and I think maybe him most of all. Watchdog Skou agreed on it as long as Arnie stayed with us, and Skou could make all the security arrangements he wanted to.”

“Thank you for having me,” Arnie said, leaning back wearily in the upholstered chair. He looked drawn and had lost a lot of weight. “I am sorry to impose…”

“Don’t be silly! If you say another word I shall throw you out and make you stay at the Mission Hotel which, as you know, is absolutely non-alcoholic. Here you get drinks. To celebrate. What would you like?” She stood and opened the bar.

“My arms feel heavy as lead,” Nils said, scowling as he moved his hand up and down. “I’ve barely enough strength to lift a glass to my mouth. That gravity, one-sixth of Earth’s, it ruins the muscles.”

“Poor dear! Shall I bottle feed you?”

“You know what you can do to give me strength!”

“You sound too exhausted. Better have a drink first I’ve made a pitcher of martinis—all right?”

“Fine. And remind me, I have a bottle of Bombay go in my suitcase for you. We have it tax-free on the Moon since they have decided to call it a free-port area until someone comes up with a better idea. The customs men, very generous, allow us to bring one bottle back. An 800,000 kilometer round trip to save twenty-five kroner in duty. The world’s mad.” He took a deep drag on the chilled drink and sighed with pleasure.

Arnie sipped at his. “I hope you will excuse all the guards and fuss, but they treat me like a national treasure—”

“As you damn well are!” Nils broke in. “With all the Daleth equipment on the Moon, you are worth a billion kroner on the hoof to any country with the money to buy you. I wish I weren’t so patriotic. I would sell you to the highest bidder and retire to Bali for life.”

Arnie smiled, almost relaxing.

“They had a conspiracy. The doctors, Skou, your husband, all of them. They thought if they made an armed fort of your home that I could come here. The weather could not be better.”

“Sailing weather,” Nils said, and drained his drink. “Where’s the boat?”

“In the water, like you asked, tied up on the south side of the harbor.”

“What a day for sailing! Why don’t we all go down there—no, damn, Arnie’s supposed to stay in the house.”

“You two go, I will be fine right here,” Arnie insisted. “I will get some sun in the garden, that is what Nils promised me.”

“No such thing,” Martha said. “Nils is going to the harbor and get all hot and tarry. He never sails the boat, just caulks seams and things. Let him get it out of his system while we loaf in the garden.”

“Well—if you don’t mind?” Nils was already leaning ›ward the door.

“Go on,” Martha laughed. “Just come back in time for inner.”

“I’ll find Skou and tell him where Fm going. Not that hey care about me, since all I know about a Daleth drive s how to push the buttons.”

Martha had to find him his work trousers, then a paint-stained shirt, then his swim trunks before he was ready and slammed out of the house. Arnie had gone to his room to change and, at the sight of all the delicious sunlight, Martha put on a bathing suit too. All Danes were sun worshipers on a day like this.

Arnie was on a lounge on the patio, and she pulled the other one up next to him.

“Wonderful,” he said. “I did not realize how much we miss color and being out of doors.” The shadow of a gull slid across the grass and up the high wooden fence. The air was still. Someone laughed, far away, and there was the distinct plock-plock of a tennis ball being played.

“How is the work going? Or as much of it as you can tell me about.”

“The only secret is the drive. For the rest it is like running a steamship company and opening up the wild West at the same time. Did you read about our Mars visit?”

“Yes, I was so jealous. When do you start selling passenger tickets?”

“Very soon. And you will have the very first one. There really are plans being made along those lines. In any case, those surface veins of uranium on Mars made the DFRS stock soar tremendously on the world markets. Money is being poured into the super-liner that the Swedes are building, mostly for cargo, but with plenty of cabins for passengers later. We will lift her by tug to the Moon and put the drive in there. The base is almost a city now, with machine shops and assembly plants. We do almost all of the manufacturing of the Daleth units there, except for standard electronics components from here. It is all going so well, no one can complain.’* He looked around for a piece of wood to touch, and found none among tf chrome-and-plastic garden furniture.

“Shall I bring you a board or something?” Marth asked, and they both laughed. “Or better yet bring you , cold drink. The yard, closed in like this, cuts off th‹ breeze, and you can actually work up a sweat in this kinc of weather.”

“Yes, please, if you will join me.”

“Try and stop me. Gin and tonic since we already started on gin.”

She came back with the drinks on a tray, silently on her bare feet, and Arnie started when he saw her.

“I didn’t mean to surprise you,” she said, handing him a glass.

“Please do not blame yourself. I know that it is I. There has been a great deal of work and tension. So it is really very good to be here. In fact it is almost as hot as Israel.”

“Do you miss Israel?” she asked, then quickly said, “I’m sorry. I know that it’s none of my business.”

The smile was gone, his face set. “Yes, I miss the country. My friends, the life there. But I think that I would do the entire thing over again in the same manner if I were given a second chance.”

“I don’t mean to pry…”

“No, Martha, it is perfectly all right. It is on my mind a good deal of the time. Traitor or hero? I myself would rather die than cause injury to Israel. Yet I had a letter, in Hebrew, no signature. ‘What would Esther Bar-Giora have thought?’ it said.”

“Your wife?”

“Yes. She looked very much like you. The same kind of hair and”—he glanced at her figure, more flesh than fabric in the diminutive bathing suit, and looked away and coughed—“the, what you might call, the same sort of build. But dark, tanned all the time. A sabra, born and grew up in Israel. One of my graduate students. She married the professor, she used to always say.” His eyes had a distant, haunted look. “She was killed in a terror raid.” He sipped his drink. In the silence that followed the distant louring of children could be heard.

“But do not let me sound too gloomy, Martha. It is too ice an afternoon. I would like to have known who sent lat letter. I wanted to tell whoever it was that I think isther would have been angry at me, but she would have aderstood. And in the end she might even have agreed with me. There must be a time when the issue of all nankind should come ahead of our concerns with our own country. You should know about that, what I mean. Born in American, now a Dane, a real citizen of the world.”

“No, not really.” She laughed to cover her confusion. “I mean I am married to a Dane, but I am still an American citizen, passport and all.” Now why had she told him about that?

“Papers,” he said, lifting his hand in a gesture of dismissal. “Meaningless. We are what we think we are. Our deeds reflect our ethos. I am stating it badly. I never did well in philosophy, or in anything other than physics and mathematics. I even failed stinks once, forgot a retort on the burner and let it explode. And I never thought much about anything other than my work. And Esther, of course, when we were married. People used to call me a dry stick, and they were right. I never played cards, nothing like that. But I could see and I could think. And watch the attempts to destroy Israel. And when the idea of the Daleth drive came closer and closer to reality, I thought more and more about what should be done with it. I remembered Nobel and his million-dollar guilty-conscience awards. I thought of the atomic scientists who had been certified or who had committed suicide. Why, I kept thinking, why can’t something be done before the discovery is revealed? Can I not turn it to the benefit of mankind instead of the destruction? The thought stayed with me, and I could not get rid of it, and—in the end—I had to act upon it. I did not think that it would be easy, but I never thought it would be this hard…”

Arnie broke off and sipped at his drink. “You must excuse me; I am talking too much. The company of men. A woman, a sympathetic ear, and you see what happens. A joke.” He smiled a twisted grin.

“No, never!” She leaned over impulsively and took h hand. “A woman would go mad if she couldn’t tell ht troubles to someone. I think that’s the trouble with me! They hold it all in until they explode and then go out and kill someone.”

“Yes, of course. Thank you. Thank you very much.” H patted her hand clumsily with his and lay back heavily eyes closed. A fat bumblebee hummed industriousl) around the hollyhock that climbed the side of the house. the only sound now in the still of the afternoon.

“Den er fin med kompasset,

Slå rommen i glasset…”

Nils sang happily in a loud monotone, scraping away at the paint blister on the cockpit cover. The harbor was deserted; on a summer Sunday like this every boat was out in the Sound. He would be too, as soon as he finished this job. He hated to see any imperfections on his Mage, so he ended up doing much more painting and polishing than sailing. Well, that was fun too. He had muscles and he liked to use them. Though they would ache tomorrow after the months of enervating lunar gravity. He was barefoot, stripped to his swim trunks, sweating greatly and enjoying himself tremendously. Singing so loud that he was unaware of the quiet footsteps on the dock behind him.

“That’s a terrible noise that you are making,” the voice said.

“Inger!” He sat up and wiped his hands on the rag. “Do you make a habit of sneaking up on me? And what the devil are you doing here?”

“Accident, if you can call fate that. I’m with friends from the Malmö Yacht Club, we’re just out for the day.” She pointed at a large cabin cruiser on the other side of the harbor. “We tied up here for lunch—and some drinks of course, you know how thirsty we Swedes get. They all went into the kro. I have to join them.”

“Not before I give you a drink—I have some bottles of beer in a bucket. My God but you look good.”

She did indeed. Inger Ahlqvist. Six feet of honey-tanned blonde, in a bikini so small that it was hardly noticeable.

“You shouldn’t walk around like that in public,” he said, aware of the tightening of the muscles in his tomach, his thighs. “It’s just criminal. And torture to a poor guy who has been playing Man in the Moon for so long that he has forgotten what a girl even looks like.”

“They look like me,” she said, and laughed. “Come on, give me that beer so I can go get my lunch. Sailing is hungry work. How is the Moon?”

“Indescribable. But you’ll be there one of these days soon. DFRS will need hostesses, and we’ll bribe you away from SAS.” He jumped down into the cockpit, landing heavier than he realized, still not adjusted to the change in gravity, and opened the cabin door. “I’ll get one for myself too. Isn’t this the weather? What have you been doing?”

He went to the far end where he had the green bottles in a bucket of water with chunks of ice. She stepped into the cockpit and leaned down to talk to him.

“The same old round. Still fun, but don’t think I haven’t envied you all this Moon and Mars travel. Do you mean what you said about the hostess thing?”