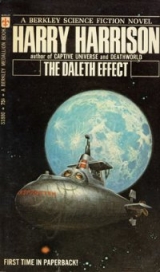

Текст книги "The Daleth Effect"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

7

With the blackboard behind him and the circle of seated, eager listeners before him, Arnie felt very much at home. As though he were back in a classroom at the university, not the wardroom of the Vitus Bering, He resisted the impulse to turn and write his name, ARNDE KLEIN, in large letters upon the board. But he did write DALETH EFFECT very clearly at the top, then the Hebrew letter ã after it.

“If you will be patient for a moment, I must give you a small amount of history in order to explain what you witnessed this morning. You will remember that Israel conducted a series of atmospheric research experiments with rockets a few years ago. The tests served a number of functions, not the least of which was to show the surrounding Arab countries that we… that is they, Israel… had home-manufactured rockets and did not depend upon the vagaries of foreign supplies. Due to the physical limitations imposed by the surrounding countries, and the size of Israel, there was very little choice of trajectories. Straight up and straight back down was all that we could do, and some very exacting control techniques had to be worked out to accomplish this. But a rocket that rose vertically and stayed directly above the launch site on the ground proved an invaluable research device for a number of disciplines. A trailing smoke cloud supplied the meteorologists with wind direction and speed at all altitudes, while internal instrumentation recordings later coordinated this with atmospheric pressure and temperature. Once out of the atmosphere there were even more experiments, but the one that we concern ourselves with now is the one that inadvertently revealed what can only be called gravimetric anomalies.” He started to write the word on the blackboard, but controlled himself at the last moment.

“My interest at this time was in quasars, and the possible source of their incomprehensible energies. Even the total annihilation of matter, as you know, cannot explain the energy generation of quasars. But this became almost incidental because—completely by chance—this rocket probe was out of the atmosphere when a solar flare started. It was there for almost fifty minutes. Other probes, in the past, have been launched as soon as a flare has been detected, but this means a lag of an hour at least after the original explosion of energy. Therefore I had the first readings to work with on the complete buildup of a solar flare. Magnetometer, cosmic ray particles—and something that looked completely irrelevant at the time: the engineering data. This drew my attention because I had been working for some years on certain aspects of the Einsteinian quantum theory that relate to gravity. This research had just proven to be a complete dead end, but it was still on my mind. So when the others discarded some of the data because they believed the telemetry was misreading due to the strong magnetic fields, I investigated in greater detail. The data was actually sound, but it showed that a wholly inexplicable force was operating that seemingly reduced the probe’s weight, but not its mass. That is to say that its gravitational mass and inertia! mass were temporarily unequal. I assigned the symbol Daleth to this discrepancy factor and then sought to find out what it was. To begin with, I at once thought of the Schwarzchild mass, or rather the application of this to the four-dimensional continuum of the Minkowski universe.

The baffled expressions on all the faces finally drew Ar-nie’s attention—including one high-ranking officer whose eyes were glazed, almost bulging—and he slowed and stopped. He coughed into his fist to cover his confusion. These were not physics students after all. Turning to the board he added another underscore to the Daleth.

“Not to go into too many details, I will attempt to explain this observation in simple language. Though you must understand that this is an approximation only of what occurred. I had something that I could not explain, though it was something that was obviously there. Like taking a dozen chicken eggs and hatching them and having an eagle come out of one. It is there, clearly enough, but why and how we do not know.”

A relieved chuckle moved across the wardroom, and there were even a few smiles as they finally found themselves understanding something that was being said. Encouraged, Arnie stayed on common ground.

“I began to work with the anomaly, first setting up mathematical models to determine its nature, then some simple experiments. In physics, as in all things, knowing just what you are looking for can be a great aid. For example, it is easier to find a criminal in a city if you have a description or a name. Once helium had been detected in the spectrum of the sun its presence was uncovered here on Earth. It had been here all the time, unnoticed until we knew what to look for. The same is true of the Daleth effect. I knew what to look for and I found answers to my questions. I speculated that it might be possible to control this…” He groped for a word. “It is not true, and I should not do it, but for the moment let us call it an ‘energy’. Remembering all the time that it is not an energy. I set up an experiment in an attempt to control this energy which had rather spectacular results. Control was possible. Once tapped, the Daleth energy could be modulated; this was little more than an application of current technology. You saw the results this morning when Blaeksprutten rose into the air. This was a very limited demonstration. There is no reason why the submarine could not have traveled above the atmosphere at speeds of our own choosing.”

A hand was raised, with positive assurance, and Arnie nodded in that direction. At least someone was listening closely enough to want to ask a question. It was an Air Force officer, looking young for the high rank that he held.

“You’ll pardon my saying this, Professor Klein, but aren’t you getting something for nothing? Which I have been taught is impossible. You are negating the Newtonian laws of motion. There is not enough power in the sub’s engines, no matter how applied, other than by a block and tackle, to lift its mass and hold it suspended. You mentioned relativity, which is based solidly on the conservation of momentum, mass energy, and electric charge. What appears to have happened here must throw at least two out of the three into doubt.”

“Very true,” Arnie agreed. “But we are not ignoring these restrictions; we are simply using a different frame of reference in which they do not apply. As an analogy I ask you to consider the act of turning a valve. A few foot pounds will open a valve that will allow compressed gas to leave a tank and expand into a bag and cause a balloon to rise. An even better comparison might be to think of yourself as hanging by a cord from that bag, high above the Earth. An ounce or so of pressure on a sharp blade will cut the cord and bring you back to the ground with highly dramatic effects.”

“But cutting the cord just releases the kinetic energy stored by lifting me to that height,” the officer said warmly. “It is the gravity of the Earth that brings me down.”

“Precisely. And it was the released gravity of Earth that permitted Blaeksprutten to fly.”

“But that is impossible!”

“Impossible or not, it happened,” an even higher ranking Air Force officer called. “You damned well better believe your own eyes’, Preben, or I’ll have you grounded.”

The officer sat down, scowling at the general laughter, which died away as Admiral Sander-Lange began to speak.

“I believe everything you say about the theory of your machine, Professor Klein, and I thank you for attempting to explain it to us. But I hope you will not be insulted when I say that, at least for me, it is not of the utmost importance. Many years back I stopped trying to understand all the boxes of tricks they were putting on my ships and set myself the task of only understanding what they did and how they could be used. Could you explain the possibilities, the things that might be accomplished by application of your Daleth effect?”

“Yes, of course. But I hope that you will understand that there are still a number of ‘ifs’ attached. If the effect can be applied as we hope—and the next experiment with Blaeksprutten will determine that—and if the energy demands are within reason to obtain the desired results, then we will have what might be called a true space drive.”

“What exactly do you mean by that?” Sander-Lange asked.

“First consider the space drive we now use, reaction rockets such as the ones that power the Soviet capsule that is now on its way to the Moon. Rockets move through application of the law of action-and-reaction. Throw something away in one direction and you move in the other. Thousands of pounds of fuel, reaction mass, must be lifted for every pound that arrives at its destination. This process is expensive, complicated, and of only limited usage. A true space drive, independent of this mass-to-load ratio, would be as functionally practical as an automobile or a seagoing ship. It would power a true spacegoing ship. The planets might become as accessible as the other parts of our own world. Since reaction mass is not to be considered, a true space drive could be run constandy, building up acceleration to midpoint in its flight, then reversing direction and decelerating continuously until it landed.

This would make a simply incredible difference in the time needed to fly to the Moon or the planets.”

“How big a difference?” someone asked. “Could you give us some specific figures?”

Arnie hesitated, thinking, but Ove Rasmussen stood to answer. “I think I can give you some help. I have been working it out while we have been talking.” He lifted his slide rule and made a few rapid calculations. “If we have a continuous acceleration and deceleration of one G—one gravity—there will be no feeling of either free fall or excess weight to passengers in the vehicle. This will be an acceleration of… nine hundred eighty—we’ll call it a thousand for simplicity—centimeters per second per second. The Moon is, on the average, about four hundred thousand kilometers distant. The result would therefore be…”

There was complete silence as he made the calculations. He read off the result, frowned, then did it over again. The answer appeared to be the same, because he looked up and smiled.

“If the Daleth effect does produce a true space drive, there is something new under the sun, gentlemen.

“We will be able to fly from here to the Moon in a little under four hours.”

During the unbelieving silence that followed he made another calculation.

“The voyage to Mars will take a bit longer. After all, the red planet is over eighty million kilometers distant at its closest conjunction. But even that voyage will be made in about thirty-nine hours. A day and three-quarters. Not very long at all.”

* * *

They were stunned. But as they thought of the possibilities opened up by the Daleth effect a babble of conversation rose, so loud that Arnie had to tap on the blackboard with his chalk to get their attention and to silence them. They listened now with a fierce attention.

“As you see, the possibilities of the exploitation of the Daleth drive are almost incalculable. We must change all of our attitudes about the size of the solar system. But before we sail off to the Moon for a weekend of exploration we must be sure that we have an adequate source of motive power. Will the drive work away from the Earth’s surface? Is it precisely controllable—that is can we make the minute course adjustments needed to reach an object of astronomical distances? Do we have a power source great enough to supply the energy demands for the voyage? Is the drive continuously reliable?

“The next flight of Blaeksprutten should answer most of these questions. The craft will attempt to rise to the top of the Earth’s atmosphere.

“As the most qualified person in regard to the drive equipment, I shall personally conduct the tests.” He looked around, jaw clamped, as though expecting to be differed with, but there was only silence. This was his day.

“Thank you. I would suggest then that the second trial be begun immediately.”

8

“I’m beginning to see why they might need an airline pilot aboard a submarine,” Nils said, spinning the wheel that sealed the lower hatch in the conning tower.

“Keep the log, will you?” Henning asked, pointing to the open book on the little navigator’s table fixed to the bulkhead.

“I’ll do just that,” Nils said, looking at his watch and making an entry. “If this thing works you’ll be the only sub commander ever to get flight pay.”

“Take us out, please, will you, Commander Wil-helmsen?” Arnie said, intent upon his instruments. “At least as far as you did the first time.”

“/a vel” Henning advanced the impeller one notch and the pumps throbbed beneath their feet. He sat in the pilot’s seat just ahead of the conning tower. The hull rose here in a protuberance that contained three round, immensely thick ports. A control wheel, very much like that in an airplane, determined direction. For turning left and right it varied the relative speed of the twin water jets that propelled the sub. Tail planes aft caused them to rise or fall.

“Two hundred meters out,” Henning announced, and eased off on the power.

“The pumps for your jets, are they mechanical?” Arnie asked.

“Yes, electrically driven.”

“Can you cut them off completely and still maintain a constant output from your generator? We have voltage regulators, but it would help if you could produce as constant a supply as is possible.”

Henning threw a series of switches. “All motor power off. There is still an instrumentation drain as well as the atmosphere equipment. I can cut them off—for a limited time—if you like?”

“No, this will be fine. I am now activating the drive unit and will rise under minimum power to a height of approximately one hundred meters.”

Nils made an entry in the log and looked at the waves splashing at the porthole nearest him. “You don’t happen to have an altimeter fitted aboard this tub, do you, Henning?”

“Not really.”

“Pity. Have to get one installed. And radar instead of that sonar. I have a feeling that you’re getting out of your depth…”

Henning had a pained look and shook his head dolefully—then glanced at the port as a vibration, more felt than heard, swept through the sub. The surface of the water was dropping at a steady rate.

“Airborne now,” he said, and looked helplessly at his useless instruments. The ascent continued; moments passed.

“One hundred meters,” Nils said, estimating th£ir height above the ship below. Arnie made a slight adjustment and turned to face them.

“There appears to be more than enough power in reserve even while the drive is holding the mass of this submarine at this altitude. The equipment is functioning well and is in no danger of overloading. Are you gentlemen ready?”

“I’m never going to be more ready.”

“Push the button or whatever, Professor. Just hanging here seems to be doing me no good.”

The humming increased and their chairs pressed up against them. Nils and Henning stared through the ports, struck silent by emotion, as the tiny submarine leapt toward the sky. A thin whistle vibrated through the hull as the air rushed past outside, scarcely louder than the sigh of the air-conditioning unit. The engine throbbed steadily. Seemingly without effort, as silendy as a film taken from an ascending rocket, their strange craft was hurling itself into the sky. The sea below seemed to smooth out, their mother ship shrinking to the size of a model, then to a bathtub toy, before the low-lying clouds closed in around them.

“This is worse than flying blind,” Nils said, his great hands clenching and unclenching. “Seat of the pants, not a single instrument other than a compass, it’s just not right.”

Arnie was the calmest of the three, too attentive to his instruments to even take a quick glimpse through one of the ports. “The next flight will have all the instrumentation,” he said. “This is a trial. Just up and down like an elevator. Meanwhile the Daleth unit shows that we are still vertical in relation to the Earth’s gravity, still moving away from it at the same speed.”

The cloud layers were thick, but soon fell away beneath their keel. Then the steady rhythm of the diesel engines changed just as Arnie said, “The current—it is dropping! What is wrong?”

Henning was in the tiny engine compartment, shouting out at them.

“Something, the fuel, I don’t know, they’re losing power.”

“The atmospheric pressure,” Nils said. “We’ve reached our ceiling. The oxygen content of the air is way down!”

The engine coughed, stuttered, almost died, and a shudder went through the submarine. An instant later they started to fall.

“Can’t you do something?” Arnie called out, working desperately at the controls. “The flow—so erratic—the Daleth effect is becoming inoperable. Can’t you stabilize the current?”

“The batteries!” Henning dived for his position as he spoke, almost floating in the air, so quickly was their fall accelerating.

He clutched at the back of his chair, missed, floated up and hit painfully against the periscope housing and bounced back. This time his fingers caught the chair and he pulled himself down into it and strapped in. He reached for the switches.

“Current on—full!”

The fall continued. Arnie glanced quickly at the other two men.

“Get ready. I have cut the drive completely. When I engage it now I am afraid that the reaction will not be gentle because—”

Metal screeched, equipment crashed and broke, and there were hoarse gasps as the sudden deceleration drove the air from their lungs. They were slammed down hard into their chairs, painfully, and for an instant they hovered at the edge of blackout as the blood drained from their brains.

Then it was over and they were gasping for air, dizzily. Henning’s face was a white mask streaked with red, bleeding from an unnoticed scalp wound where his skull had struck the periscope. Outside there were only clouds. The engine ran smoothly and the air hushed from the vents, soft background to their rough breathing.

“Let us not—” Nils said, taking a deep breath. “Let us not… do that again!”

“We are maintaining altitude with no lateral motion/’ Arnie said, his words calm despite the hardness of his breathing. “Do you wish to return—or to complete the test?”

“As long as this doesn’t happen again, I’m for going on,” Nils said.

“Agreed. But I suggest that we operate on the batteries.”

“How is the charge?”

“Excellent. Down less than five percent.”

“We will go back up. Let me know when the charge is down to seventy percent and we will return. That should give us an acceptable safety margin. Plus the fact that engines can be restarted when we are low enough.”

It was smooth, exhilarating. The clouds dropped below them and the engine labored. Henning shut it down and sealed the air intake. They rose.

“Five thousand meters high at least,” Nils said, squinting at the cloud cover below with a pilot’s eye. “Most of the atmosphere is below us now.”

“Then I can step up the acceleration. Please note the time.”

“It’s all in the log. Some of it in a very shaky handwriting, I can tell you.”

The curvature of the Earth was visible, the atmosphere a blue band above it tapering into the black of space. The brighter stars could be seen; the sun burned like a beacon and, shining through the port, threw a patch of eye-hurting brightness onto the deck. The upward pressure ceased.

“Here we are,” Arnie said. “The equipment is functioning well, we are holding our position. Can anyone estimate our altitude?”

“One hundred fifty kilometers,” Nils said. “Ninety or a hundred miles. It looks very much like the pictures shot from the satellites at that altitude.”

“Battery reserve seventy-five percent and dropping slowly.”

“Yes, it takes power to hover, scarcely less than for acceleration.”

“Then we’ve done it!” Nils said and, even louder when the enormity struck him, “We’ve done it! We can go anywhere—do anything. We’ve really done it…”

“Battery reserve nearing seventy percent.”

“We will go down then.”

“A little slower than last time?”

“You can be sure of that.”

More gently than a falling leaf, the submarine dropped. They passed through a silvery layer of high cirrus clouds.

“Won’t we be coming down much further to the west?” Nils asked. “The Earth will have rotated out from under us so we won’t be able to set down in the same spot.”

“No, I have compensated for that motion. We should be no more than a mile or two from the original position.”

“Then I had better get on the radio.” Henning switched it on. “Well be in range soon, and we’ll want to tell them.”

A voice came clearly through the background static, speaking the fast, slang-filled Copenhagen Danish that only a native of that city would be able to understand.

“…dive, daughter, dive, and don’t come up for air. Swim deep, little sister, swim deep…”

“What on earth are they talking about?” Araie asked, looking up, surprised.

“That!” Nils said, looking out the port and turning his head swiftly to follow the silver swept-wing forms that flashed by below. “Russian MIG. We’re just out of the clouds and I don’t think they saw us. Can we drop any faster?”

“Hold on.”

A twist of Arnie’s fingers pushed their stomachs up into their throats.

“Let me know when we are about two hundred meters above the water,” he said calmly. “So I can slow the 4rop before we hit.”

Nils clutched the arms of his chair to keep from floating up despite his belt. The leaden surface of the Baltic flashed toward them, closer and closer, the waves with white caps were visible, and the Vitus Bering off to one side.

“Closer… closer… NOW!”

They were slammed down, loose equipment rolled, sliding across the suddenly canted deck. Then an even more powerful force crashed into the sub, jarring the entire hull, as they plunged beneath the surface.

“Will you please take over, Commander Wilhelm-sen,” Arnie said, and for the first time his voice was a bit uneven. “I am shutting down tht Daleth unit.”

The pumps throbbed to life and Henning almost caressed his control panel. It was hard to fly as a passenger in one’s own submarine. He whistled between his teeth as he made a slow turn and angled up to periscope depth.

“Take a look through the periscope, will you, Hansen? It’s easy enough to use, just like they do in the movies.”

“Up periscope!” Nils charted, slapping the handles down and twisting his cap backward. He ground his face into the rubber cushion. “I can’t see blast-all.”

“Turn the knob to focus the lenses.”

“Yes, that’s better. The ship’s off to port about thirty degrees.” He swept the periscope in a circle. “No other ships in sight. This thing doesn’t have a big enough field, so I can’t tell about the sky.”

“We’ll have to take a chance. I’ll bring her up a bit so the aerial is clear.”

The radio hissed with background noise, then a voice broke in, died away and returned an instant later.

“Hello, Blaeksprutten, can you hear me? Over. Hello.”

“Blaeksprutten here. What’s happening? Over.”

“It is believed that you appeared on the Russian early warning radar screens. MIGs have been all over the area ever since you went up. None in sight now. We think that they did not see you come in. Please close on us and report on test. Over.”

Arnie took up the microphone.

“Equipment functioned perfectly. No problems. Estimated height of a hundred fifty kilometers reached on battery power. Over.”

He flicked the switch and the sound of distant cheering poured from the loudspeaker.