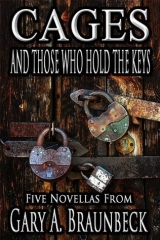

Текст книги "Cages and Those Who Hold the Keys"

Автор книги: Gary A. Braunbeck

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

(Now more than ever it seems rich to die . . .) learn.

What had he been thinking, anyway, coming in here like this? This would throw off the schedule. Postpone the pudding. Delay the spoons.

(. . . cease upon the midnight with no pain . . .)

That wouldn’t do; wouldn’t do one little bit.

“Sir,” said the other woman, now standing beside the receptionist. “Are you all right?”

Martin looked up, one hand covering his mouth, wanting to shrug, to give her some sort of physical response, but he couldn’t think of anything to do or say.

The other woman came around, slowly opening the small waist-level door that separated the reception office from where Martin was standing. Moving toward him, she carefully raised her hands to her sides as if preparing to either catch something or grab him. Maybe she wanted to dance a waltz; who knew? “What’s in the bag?” she asked.

“Huh? Oh . . . stuff. Pudding cups. Medicine.” He realized that the watercolor was still tucked under his arm, and set about slipping it back into the bag.

“What kind of medicine?” asked the woman.

“Just . . . y’know, medicine. Doctors gave it to me. I mean, some of it was Mom’s, some of it was Dad’s. Most of it was stuff the doctors gave to me after my folks died. To help me sleep, calm me down, blah-blah-blah, cha-cha-cha, so on and so forth.” The woman stopped a few feet away from him. “What’s your name?” “Martin Tyler.” “My name’s Barbara Hayes, Martin.” Why couldn’t he stop sweating? Crying. Whatever. “Nice to meet you.” “Can you tell me what you’ve taken, and how much of it?”

“Not really. I’d have to check . . . check the schedule.” The watercolor safely back in place, he tucked the grocery bag under his arm and searched through his pockets for the piece of paper on which he’d written down everything. He located it at last, unfolded it, and found that he couldn’t get his eyes to focus; something was making his vision blurry, like he was underwater.

Why was it so damned hot in here? He’d never sweated—

–not sweating, pal; try to keep up– —like this before. “I can’t seem to . . . to read my own handwriting.” He offered the paper to Barbara Hayes. “Can you give it a try?” “Yes,” she said, taking it from him.

“I’m a custodian,” he said, suddenly feeling as if he needed to explain himself to this woman. “But I’m really good at it. I wanted to be a writer once, I even studied English and American Literature for a couple of years at OSU, but I dropped out . . . can’t remember why, not just now. I figured that I could always go back to school but then . . . things happen, you know? Dad died last June and then Mom died this April and I thought I was doing okay, all things considered, I mean, considering what a hoo-ha blue-ribbon year-or-so it’d been, and I kept thinking that it wasn’t so bad, y’know, they’d both been really sick for a while and I was expecting them to die—Dad had cancer that spread from his prostate to his liver to his stomach and finally to his brain . . . Mom’s bad heart just gave up the fight, which wasn’t a big surprise after spending so much time helping me take care of Dad, so it wasn’t like I wasn’t ready for it, understand? I was doing okay, really, I was, but each time one of them died I’d have to gather up all their stuff and I wound up with all this medicine and couldn’t sleep for shit and I was nervous and shaky and it seemed like every time I turned around some doctor was giving me a prescription for this kind of sleeping pill or that kind of tranquilizer or some other kind of goddamn anti-depressant happy-happy-joy-joy pill and I woke up this morning and couldn’t remember if I’d turned the ringer off on my phone, so I checked it and the ringer was on but I checked my voicemail, anyway—it’d been five days, after all—and there weren’t any messages and I just got to wondering about how long I’d be missing before someone noticed and . . . .”

He stopped, bored with the incessant droning monotone of his voice, but the woman standing across from him, Barbara Hayes, Dr. Barbara Hayes, a practicing psychiatrist who volunteered at the Crisis Center two nights every month, did not hear a droning monotone; what she heard was a man speaking in a rapid, deadly cadence, whose voice was so tight with hysteria that the words tumbling out of his mouth hit the floor like shards of shattered glass.

She read what was written on the paper, then looked back up at him. “This is very organized, Martin. Extremely well-researched and well-planned.”

“Thank you.”

“How long have you been planning this?”

A shrug. “Three, four months. Off and on.”

She nodded. “And all this medication was either leftover from your parents’ treatments or prescribed to you by other physicians?”

“I bought some of it off the Internet. It was easier than I’d thought it’d be. Expensive, but easy.” “Martin?” “Yes?” “Why do you want to die?”

The unexpected directness of her question seemed to jar something loose inside him; he blinked, wiped his eyes, then pulled in a slow, hard, snot-filled breath, considering his reply. While he was doing this, Dr. Hayes looked at the receptionist, who nodded her understanding and hit the speed-dial button.

Martin was peripherally aware of the receptionist whispering to someone on the phone—maybe she was calling her boyfriend, making arrangements to meet for a late dinner or a snack or something when her shift ended (that was nice that she had someone to call, he bet they were a cute couple), but mostly he wanted to give the correct answer to the other woman’s question.

“I don’t know that it’s . . . it’s so much I want to die,” he said. “It’s just that I really don’t think I’ve been alive for a while, just sort of . . . breathing and taking up space, so . . . if there’s a third alternative that I’ve . . . overlooked, I’m all ears.” “Why do you feel this way, Martin?”

Nibby, isn’t she? He looked down at his hands. Where was the grocery bag?

He looked up again. Barbara Hayes was holding it. When had he given it to her? He should have given her the spoons. She couldn’t chow down on the pudding without the spoons. Well, he supposed she could, but it’d be kind of messy, and she didn’t look like the messy type and . . . hadn’t she asked him something?

“. . . were both sick for so long,” he heard himself saying. “If I wasn’t at work, then I was driving one of them to or from their doctors or treatments, straightening up the house—did I tell you that I’m a custodian? And a pretty good one. I always kept their house clean, their medicines organized—got some of those pill containers so I could put each day’s dosages into separate compartments in case one of them lost track of what they were supposed to take and when and . . .” He looked directly into her eyes for the first time. “You know, if you’re looking for a reason, just one, some Holy Grail of reasons . . . I can’t give it to you.” “There usually isn’t just one reason, Martin.” “Barbara?” said the receptionist; then, to Martin: “I apologize for interrupting you.” “. . . s’okay . . .” The receptionist turned back to Dr. Hayes. “They’re expecting you.” “Thanks. Martin?”

Woozy . . . damn but he was getting woozy. “Yes?”

“Did you drive yourself here?”

“Sort of . . . I mean, yes. I mean, I wasn’t really driving here, I was gonna go to . . . piss on it—my car’s outside. I left it parked over by the light.” “May I have the keys, please?” He handed them to her without question or argument. “Do you mind if I take you someplace, Martin? Someplace where there are people who can help?”

He wanted to tell her that it wasn’t a good idea, her getting into a car with a stranger, what was she thinking, but then a door opened behind him and a large, well-muscled man came into the area. “Is this him?” the man asked Dr. Hayes.

“This is Martin,” she replied, a hint of reprimand in her voice. “Martin, this is Craig. Craig is one of our volunteers. He’ll be riding along with us, if that’s all right.”

“. . . more the merrier . . .” He was feeling very . . . shiny. And dizzy. And woozy and weak. This might actually be fun if he was eating a pizza and watching Yellow Submarine.

Dr. Hayes went out to get the car and Craig took hold of Martin’s elbow. “What say you and me step out for a little air, Martin? How’s that sound?”

Sounds like you’re trying to get rid of me is what he thought; what he said was:

“. . . okay . . .”

Outside, he almost tripped over the body of the camera creature that now lay in the middle of the sidewalk, its body smashed and broken in half, one brass eye blown from its socket, trailing wires, connectors, and blood; its lower half had been split open, spilling a grotesque snarl of intestines: cogs, gears, looping tubes, and something that looked like raspberry jelly; one of its wolf’s-legs had been wrenched too far forward, the bone broken, one jagged edge pushing up through the fur; and the remaining wing, barely attached now except for a few strands of sinew and wire, jerked and shuddered. Scattered elsewhere were sections of beak and splinters of wood and other things that had once been part of its body; things mechanical, things organic, things that looked like a glistening amalgamation of the two. Some of it had spattered against the windows and walls of the buildings, and was now slowly crawling down toward the pavement, leaving a slick dark trail in its wake. Martin felt both nauseous and sad as he looked at the demolished pulp of the creature’s remains.

Something had torn it apart in a rage, then thrown it from the rooftop.

Martin looked up and saw the six-year-old boy he’d once been sitting on one of the fire escape landings, grasping two of the horizontal railing bars, pressing his face between them and sniffling. His eyes were red and puffy. His expression told Martin everything he needed to know: It wasn’t me, and it didn’t fall.

“What happened?’ Martin asked aloud.

“Dr. Hayes went to get your car, remember?” replied Craig. “You just take it easy, we’ll get you all taken care of.”

Martin ignored him. Up on the roof, passing under the glow of the streetlight, he caught sight of something massive and closed his eyes; though he’d glimpsed it only for a second—part of a shoulder? the back of its head?—whatever: it was fifty miles past ugly. It had made a deep slobbering sound, radiated an air of threat and corruption, one that Martin could feel even now, covering his face and hands in thin patina of dread and

. . . rot.

Yeah, that was definitely the word for it: rot.

Then Dr. Hayes pulled up in Martin’s car and Craig was pushing him into the back seat, sitting next to him as Dr. Hayes pulled away and asked Craig if he’d brought it, and Martin wondered what they were talking about, then Craig said yes and pulled a small bottle of something out of his pocket, unscrewed the cap, and handed it to Martin as Dr. Hayes asked how long ago he’d taken the first dose of pudding and pills, and Martin said he wasn’t sure, maybe forty minutes ago, probably less, and Dr. Hayes said all right, he needed to drink that right now, please, and Martin realized that he was thirsty, so he brought the small green bottle to his lips and chugged it—it tasted like castor-oil crap but he didn’t care, it was cold and wet and felt good going down—then he thanked Craig and handed the bottle back to him and lay back his head, closing his eyes, trying to shake off the feeling of decay and corruption that still clung to him, trying not to think about the little bit of the thing that he’d been able to see, wondering where the little boy would go now, and for a few moments (minutes? . . . hard to tell) he just enjoyed the ride, responding to questions every now and then when Dr. Hayes asked them, telling her his doctor’s name somewhere in there, then his stomach rumbled and he got that funny swelling feeling in the middle of his throat that quickly rose into his mouth and he managed to say, “I think I’m gonna be—” before Dr. Hayes pulled over and Craig threw open the door and Martin fell out on his hand and knees, vomiting up what felt like everything he’d put into his stomach since he was three, vomiting with such force that he wouldn’t have been surprised to see his shoes come flying out, but it was done soon enough, it was finished, and so was he, he knew it, and next thing Craig was helping him back into the car, wiping off his mouth and chin with a handkerchief, and they were off again, and when they arrived at The Center everyone there was very nice and very helpful, Dr. Hayes talked to them, and Martin signed something about agreeing to the rules and treatment, he gave them all the contents of his pockets and they told him the items would be returned to him after he’d been processed, then Dr. Hayes gave him a shot and one of the staff took him back to his room that had a single bed, a chair, an empty student desk with a clip-on lamp, and the staffer helped Martin into bed, and for the first time in his life, he was, literally, asleep before his head hit the pillow. It was a deep, solid sleep, born as much from complete exhaustion as it was from the tranquilizer given to him. He did not dream; he would not have remembered even if he had. And so passed the only peaceful night Martin Tyler would know in Buzzland.

2

He was awakened at eight a.m. when a burly attendant did not so much knock on as pummel his door, shove it open, flip on the too-bright overhead lights, and bellow in a sing-song yet impatient voice, “Time to get up, come on, breakfast in five minutes,” before walking on to repeat the ritual elsewhere.

Martin swung his feet down onto the floor, and for a moment sat staring at the light-colored tile there. Hadn’t he read something once about how places like this used neutral-to-soothing colors? Nothing that would agitate someone? Bland but not boring. And why was he pissing away brain cells pondering the decorating scheme?

This floor needs to be stripped and re-waxed, he thought. A good buffing wouldn’t hurt things, either.

He swallowed, was barely able to work up enough saliva to complete the action, and realized he had a major case of cotton mouth. It also felt like his stomach had imploded—Christ, he was hungry.

Breakfast in five minutes.

He stood, pulled in a deep breath, and took exactly three steps toward the door before his right leg buckled and his left decided that looked like the thing to do and joined it, which is why he was sitting on his ass in the middle of the floor when Sing-Song the Impatient came by again.

“Having a little trouble finding your legs this morning?”

“No, I found them just fine. It’s getting them to cooperate that seems to be . . .” He couldn’t think of any way to finish that, so didn’t bother trying.

The attendant—whose name tag identified him as B. WILSON—came into the room and helped Martin to his feet. “Want me to lend you a hand getting to the dining area?” “If you don’t mind.” And as the attendant was helping him up, Martin asked, “What’s the ‘B’ stand for?” “Bernard. But everybody just calls me Bernie.” “But you prefer ‘Bernard’, don’t you?” The attendant looked at him. “Actually, yes, I do. How’d you guess?” “‘Bernard’ sounds like a good, strong name. ‘Bernie’ sounds like some weasel bookie whose math is always questionable.”

Bernard laughed. “I like that. If you can make me laugh, then you ain’t as far gone as you think. C’mon, food’s getting cold.”

Breakfast was scrambled eggs, three links of sausage, toast, orange juice, milk, tea or coffee, and a fruit cup. It was brought in (as were all meals) in plastic-covered hospital serving trays. Clients were allowed to use only plastic utensils (all of which had to be accounted for at meal’s end), coffee and tea were always decaffeinated, you were allowed only three small packets of sugar, and if you were in a mood and didn’t want to eat, you went hungry until the next meal was delivered.

The main area—which also served as the dining room, break area, television room, group therapy space, and activities room—consisted of two large, long folding tables with a dozen folding chairs, a small sofa and two easy chairs that had seen better days (judging from the amount of duct tape used to repair the various tears and gashes), a color television with an actual honest-to-God channel dial, a VCR that appeared to have fallen from the cargo hold of a plane cruising at twenty thousand feet but somehow still worked, a shelf filled with donated books and videotapes, a coffee table whose surface was hidden beneath piles of magazines (most of them at least six months out of date), and a single wire mesh-covered window that looked out on a parking lot with two Dumpsters squatting at the edge. There was only one door for people to enter and exit by, and that had to be opened electronically from inside the nurses’ station. As for decorations, the walls sported bulletin boards with various outdated announcements tacked to them, posters of the cute-kitty Hang In There! variety, pictures and watercolors drawn by children who’d come to visit parents or relatives, and a large dry-erase board where the daily schedule was written:

8:00 – 8:30 – Breakfast and Morning Medication

8:30 – 9:00 – Showers

9:00 – 10:00 – Individual Sessions

10:30 – Noon – Group Session #1

Noon – 1:00 – Lunch and Afternoon Medications

1:00 – 1:30 – Free Time

1:30 – 3:00 – Group Session #2

3:00 – 3:30 – Free Time

3:30 – 4:30 – Individual Sessions

4:30 – 5:30 – Dinner and First Evening Medications

5:30 – 11:00 – Socialization

11:00 – 11:15 – Wash-Up and Second Evening Medications

11:15 – Lights Out

Martin was already worn out from just reading it.

Look on the bright side, he thought . . . then couldn’t come up with any way to finish it.

He was starting in on his second sausage link when one of the nurses—an attractive black woman in her early fifties—walked up to the board, picked up a red marker, and made a large red X through everything between 9:00 and Noon. As she passed by Martin, she stopped for a moment and smiled. “We’ve only got three clients right now, Martin, including yourself, I think, and the doctor here doesn’t like to conduct group meetings if there’s less than four—but don’t worry, we’ll have a fourth soon enough, probably more, and probably in time for the second session; it’s Friday, and we tend to get full-up for the weekend. You came in during one of our rare slow periods.”

“So I’ve got nothing to do between now and lunch?”

The nurse shook her head. “I didn’t say that. We’ve got a gymnasium of sorts around the corner and through the only door there It’s mostly just a basketball court, but you can walk around or shoot some hoops if you want—be careful, though: there’s four steps that lead down onto the court once you go through the door, and they take some folks by surprise. Anyway, Dr. Hayes will be in around ten a.m. to talk you through things. In the meantime, my name’s Ethel; if you need anything, just knock on the nurses’ station door, all right?” She pointed to the station, which was actually an oversized glass-walled cubicle separating the main area from the sleeping rooms; you had to walk (squeeze, almost) through a semi-tight hallway to move from the bedroom corridor into the main area, and because the nurses’ station had glass walls on all sides, at no time were you out of anyone’s sight; even the ultra-small smoking room could be watched from there, despite its having a door that closed it off from view of the main area.

Martin took in all of this with a single, sweeping glance. “Looks like you keep a close eye on everything.”

“We do,” replied Ethel; it was both an answer and a warning. “Now, you finish your breakfast and I’ll go get your medicine.” On her way out, Ethel stopped long enough to turn on the television: a network morning news show, two oh-so-pretty hosts chatting incessantly about nothing in particular and making it sound like the most profound thing they’d ever discussed.

Martin was, for the moment, alone in the main area. He chewed his sausage—which was surprisingly flavorful—and wondered where the other clients were. Hadn’t Bernard woken everyone in the same whimsical manner? And why was Ethel—the person he assumed was in charge—unsure of how many clients they had right now? That seemed like the kind of thing they’d keep a close count on. So what was the deal?

Maybe if he didn’t eat his food too quickly, someone else would show. He suddenly wanted company.

As if she’d read his mind, Ethel appeared a few moments later with a small paper cup in her hand. “Here you go.” Martin took the cup from her, saw it had five—five?—pills, tossed them all into his mouth, downing them with a deep drink of orange juice.

“Open your mouth, please,” said Ethel, clicking on a small penlight.

Martin did; Ethel shone the light into his mouth. “Lift your tongue for me.”

He complied, Ethel nodded her head, clicked off the light, and started to walk away. Martin called her name and she turned around.

“Do you have to go?” he asked. “It’d be nice to . . . have someone to talk to.”

“Martin, come this time tomorrow, if not sooner, you’re gonna be looking back at this time by yourself as the good old days. Enjoy the quiet while it’s yours to enjoy. If you’re still hungry after you finish, they brought extra trays of food—they always bring extras; have some more if you want. What doesn’t get eaten goes down the disposal.” And with a bright and sincere smile, she went back into the nurses’ station, closed the door, and took her seat at one of the desks; another nurse, this one much younger, with porcelain-doll skin and a head of lustrous red hair, was typing something into her computer while talking to Bernard, who caught sight of Martin through the glass and gave him a quick nod.

Martin looked down at the food remaining on his tray and wondered how many trays like this the hospital kitchen had to wash every day, and just as quickly remembered all the times he’d watched his mother standing at the sink washing dishes, her and Dad having never been able to afford a dishwasher, and as he stared at this remembered image of her arthritic hands slipping dirty dishes into hot soapy water (while she hummed Charley Pride’s “Kiss An Angel Good Morning,” her favorite song), he wondered how many hours of her life she’d spent like that, alone in the kitchen, after the meals, standing at the sink washing dishes; had she ever gotten tired of it? Did she wish she’d been able to afford a dishwasher so she didn’t have to spend so much time on this chore that no one else really noticed or thought about unless it wasn’t done? Did she ever want someone else in the kitchen with her, someone to talk to while she performed this thankless task in a day filled with thankless tasks? How much of her life had she spent washing . . . ?

Martin set down his plastic fork and knife, lowered his head, and wept into his hands. He could try thinking about Dad but odds were he’d just come up with some equally happy image alive with equally cheerful thoughts. Christ! Why was it that the bad memories were always broadcast in high-definition crystal clarity, while the good ones could only be found using an old set of rabbit-ears that obscured them in static and snow?