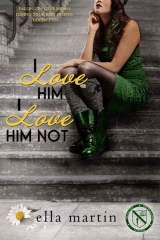

Текст книги "I Love Him, I Love Him Not "

Автор книги: Ella Martin

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Chapter Sixteen

After delivering the news, Mom and Dr. Griffin insisted I go home immediately and not go to school the rest of the week. I wasn’t going to complain about skipping classes, so I didn’t put up much of a fight, but I also didn’t know why they felt like I had to be there. I didn’t do much except sign for the flowers that arrived almost every hour and keep a list of who sent what so my mom would know whom to thank. It was almost like my dad’s friends didn’t realize they’d been estranged for years. It was crazy. My mom had already remarried, but she still wore black and acted like a grieving widow. Even stranger, Dr. Griffin didn’t seem to mind. It was almost as though he encouraged her.

His behavior was odd in general, though. I caught him watching me a few times, observing my every move as if he was waiting for me to blow up or burst into tears or something. I was sure my response – or lack thereof – disappointed him, or maybe worried him. I wasn’t angry about my dad’s death, and I certainly wasn’t sad. It was a nonevent in my world. I couldn’t avoid my stepfather indefinitely, though.

Two days after my dad died, Dr. Griffin found me in the kitchen as I picked at a bowl of chili Ally’s mom had brought over the previous evening.

“How are you holding up today?” he said as he slid onto the stool beside me.

I narrowed my eyes and pointed my spoon at him. “You know, whenever you ask a question, I’m not sure if you’re asking as a therapist or whatever.”

He grinned. “Which is easier for you to talk to?”

“No offense, Dr. Griffin, but I don’t have much to say.”

“When are you going to start calling me Rob?”

I smiled back though I inwardly groaned. Referring to him by his first name still felt weird, like we were supposed to try to be best friends or something.

“How’s she doing?” I asked after a while, my eyes raised in the direction of where Mom was resting upstairs.

He tilted his head and pressed his lips together. “She’s grieving, of course. And that’s to be expected.”

“Is she going to be okay?”

“Of course.” He gave me a curious look. “Grief’s a different process for everyone, Talia. She’s working through it.”

I let that sink in for a moment before I said, “Aren’t you weirded out by any of this?”

“No. Why would it be weird?”

I blinked a few times, surprised by his question. “Well, like, they’ve been divorced for a few years,” I said. “And she’s married to you now, but she’s all weepy and stuff. That doesn’t seem odd to you?”

Dr. Griffin put his elbows on the counter and steepled his fingers. “Is that what you think? That this is strange?”

I glanced at him uneasily. “You’re doing it again. Answering questions with questions.” I pointed my spoon at him again. “Very therapist-like. Dr. Brinkley would be proud.”

He laughed. “Occupational hazard.” He cleared his throat. “Talia, I want you to understand something.”

Oh, boy, I thought. A lecture. I braced myself.

“Your parents were married for fourteen years and they were together a long time before that. Paula loved Vince enough to want to build a life with him. They built dreams together, built a life together.” His eyes bored into mine. “Do you really think she could just turn that off?”

“He didn’t deserve her,” I said, pushing my bowl away.

“Maybe he didn’t.”

“No,” I said, emphasizing that word as much as I could to make him understand. “He was a monster.” I whispered the last word even as I choked on it. “He was horrible and said awful, awful things, and—”

“And he made mistakes,” he finished for me. “We all do that.”

“A mistake is when you forget to carry the one when you’re adding something in your head. Or going straight instead of taking a left at the corner. What he did was….” I fumbled for the words. I thought of the yelling that piqued my curiosity enough to leave my room and go downstairs. I remembered seeing my father towering over my mother, shrinking where she stood under the weight of all his cruelty. I didn’t even know what the fight was about; I never knew what they were about. I only stepped in because I wanted it to stop.

“What he did was way worse,” I finally managed to say.

Dr. Griffin didn’t speak. He was one of the only people who knew what really happened the night my dad left, and he still didn’t say anything. He just kept watching me.

I wondered if his silence was an occupational hazard, too.

“There aren’t many people you get to choose to be in your life,” he said at last. His mouth curved into a sad smile. “You can’t choose your parents, right? But your mom chose your dad, and she wanted to spend the rest of her life with him, for better or worse.”

I narrowed my eyes. I heard his words, but they didn’t make sense. “It definitely got worse.”

He paused before nodding. “I’m sure it wasn’t always like that, though. And I think if you’d let yourself forgive him—”

“I was ten!” I balled my hands into tight fists and folded my arms across my chest. “All I wanted to do was get him to stop yelling at her, and he hit me.” I looked away. “Knocked me into the wall and then turned around and blamed my mom for making him do that. Like it was somehow her fault he was such a….” I couldn’t think of the right words. Everything that came to mind didn’t seem right to say in front of my stepfather.

He didn’t say anything for a while. Every now and then an ice cube would fall from the dispenser in the freezer, but we were otherwise quiet and still.

“I’m sure you can remember some good times if you try,” he said quietly.

I let out a snort. “I think it’s better if I don’t.”

He nodded. “And that’s okay, too. You need to process grief in your own way, in your own time.” He put his hand on my shoulder. “Whenever you’re ready.” He stood and left the room. I watched his retreating figure before I reached for my bowl and turned my attention back to my lunch, grateful for the solitude.

If Dr. Griffin was right and everyone had ways of dealing with death and stuff, I was happy to embrace mine alone.

Chapter Seventeen

My dad’s memorial service the following day was surreal. He’d often said he wanted his remains cremated and his ashes scattered in the Pacific Ocean, so there wasn’t a viewing or anything. My grandparents on my mom’s side were vacationing in New Zealand, but my dad’s family – all people I hadn’t seen for more than six or seven years – still flew in from all over the country. Even my cousin Pete, the only family member I’d kind of kept in touch with, was there.

There was a big argument that morning over who’d be allowed on the yacht to see my dad’s remains float out to sea. Only nine people were allowed, and everyone seemed to be jockeying for position. My grandmother insisted my mom had no right to be on the boat, but Mom said because she was paying for everything, she had the right to go wherever she wanted. At this my grandmother mumbled something in Italian. I’d never quite gotten the hang of the language, but I knew what an inferno was and I could guess she told my mom to go to a not-very-nice place.

I volunteered to give up my place and stay home to entertain the rest of the mourners, but my presence was the one thing my mother and grandmother could agree upon. Plus my mom knew my idea of entertaining guests was hiding in my room.

“Channel Islands is so far away,” I said from the back seat of Dr. Griffin’s car as we neared the marina. “Why couldn’t we just go to the Malibu Pier and toss his ashes over the edge? At least he’d be in the ocean. I mean, it’s not like he’d really know.”

My mother sighed. “There are ordinances and laws governing these things, Talia.”

“So there’s, like, the Cremation Police?” I smiled at my own joke. Maybe that could be the name of Jake’s next band.

“Paula, does it say which lot to park in?” Dr. Griffin said as we neared the marina.

I peered out the window. In the distance, ships’ masts stuck straight in the air while palm trees swayed in the ocean breeze. The surface of the water looked almost silver as it reflected the overcast sky.

“All I know is that it’s moored in the southwest section.” Mom rifled through some papers in her lap before turning to him. “It’s called The Sleep.”

“That’s an awful name for a boat,” I said.

She turned to look back at me. “Are you wearing your patch?”

I froze. Though I knew we’d be on a boat, the thought to put on one of my motion sickness patches hadn’t occurred to me.

“No,” I said, and she let out a heavy sigh. “What? You said we’d only be out there for, like, an hour.”

“Yes, but it’s been raining the last few days, and the surf’s choppy. You know how you get when there’s only the tiniest bit of turbulence on a plane.”

I could tell she was exasperated, but it was an honest mistake. I mean, it wasn’t like I wore the patch every day.

“Fine. I’ll stay in the car with Dr. Griffin.”

“No,” they said simultaneously. Mom straightened in her seat and faced forward again. “That’s not an option,” she added.

I’d never seen my mother as stressed about anything as she was that day. I had to give her credit; she took care of my dad’s cremation and memorial services by herself. I was pretty sure my grandmother’s presence and silent critiques contributed to keeping her on edge.

A small group was gathered at the far end of the dock. I could tell who’d come from northern, snowy climates because they weren’t clutching their scarves and coats the way I did when I stepped out of the car into the late January air. A cold ocean breeze assaulted my bare legs, and I wished I was in jeans and a sweatshirt instead of the black dress my mother insisted I wear. The chilly air also reminded me why I didn’t go to the beach in the winter. I loved the sweet, briny smell of the ocean, but not when inhaling it meant freezing the insides of my nose.

I greeted my grandmother with a quick kiss on the cheek but got shooed away when she burst into tears. I’d remembered her as a strong woman with a stern brow who spoke to me only in short, clipped sentences. A single look from her had been known to freeze grown men where they stood and make small children cry. But the weeping eighty-something-year-old woman who stood before me only vaguely resembled the grandmother I knew.

That’s what real grief looks like, I thought. And I felt like such a hypocrite as I stood among the mourners because I felt nothing.

****

My stomach churned as I watched gray clumps of ash bobbing on the surface of the water. I closed my eyes, but it only made things worse. Each time the boat moved, my stomach’s contents shook like salad dressing in a bottle.

And the boat moved a lot.

“I shouldn’t have had yogurt for breakfast,” I said to my mom.

“Don’t you dare.” She pressed her lips together into a tight line and glared at me. “I won’t let you spoil this for your grandmother. She hates me as it is.”

Bile rose into my throat. My stomach lurched. I put my hand to my mouth, willing the nausea to subside.

How much longer? I wondered. There was no way I was going to last. I sent up a hasty prayer to any listening deity, promising to never leave home without my motion sickness patch if I could make it through my dad’s funeral without puking.

The captain was speaking again, but I tuned him out. I had more important things to focus on.

Like not throwing up.

I needed to focus on something other than my stomach. My bright orange life jacket smelled of old plastic, and I doubted it would keep me afloat for long. A cold breeze stung my bare cheeks, tiny daggers attacking each pore. My grandmother’s sobbing seemed to be getting louder. Seagulls squawked overhead as though demanding a food offering as payment for dumping my father’s remains in their territory. I looked out to sea, where the ocean met the sky, and concentrated on the horizon’s steady line.

Shallow breaths, I said to myself. In and out. In and out.

The captain invited us to take our flowers and send them out to sea with the ashes. I rooted my feet. Movement was my enemy. I had no intention of going anywhere.

One by one, the mourners paused at the bow before tossing cut flowers into the ocean. Mom nudged me, and I shook my head.

“I can’t,” I said with a furtive glance in her direction, hoping she wouldn’t force me. When she nodded, I knew I must’ve been a shade of green. Maybe not emerald– or grass-green, but green. Like chartreuse or whatever.

In and out. In and out. My stomach lurched again. I needed to find a new point of focus.

“Vincenzo!” my grandmother cried with a heaving sob. My dad’s cousins gasped, someone screamed, and I looked out into the water in time to see a big splash as my grandmother fell overboard.

Chapter Eighteen

“Please tell me someone caught that on video,” Finn said later that afternoon after I’d relayed what had happened at the service. “I’d pay to watch that.”

“Finn, that’s awful,” Ally said as she swiped at his arm. “The poor woman just lost her son.” She straightened her spine and folded her hands in her lap. “Show a little respect.”

Beside me on the couch, Jake laced his fingers through mine and squeezed. I smiled. My friends had come over after school, and though I’d seen everyone with their parents earlier in the week, I was so happy to be able to talk to them away from my stepfather’s watchful eye. I knew he meant well, but I was kind of over it.

My cousin Pete laughed. “Nah, I’m with Finn,” he said. “I’ve heard six different people tell that story at least three times each, and it’s funny every time.”

“I don’t know how you kept a straight face,” Finn said.

Bianca furrowed her brow. “So, like, did she jump in? Or…?”

“That’s the punch line. I guess she was trying to toss in this giant wreath, and she fell in with it instead. That’s what Mom said, anyway.” I fought back a snicker and added, “She was not pleased.”

That was an understatement. My grandmother had to be wrapped in blankets once they plucked her out of the frigid waters, and she spent the entire trip back to the marina complaining about my mom and how my dad deserved a proper burial instead of being tossed into the water like the prior day’s garbage. Never mind that my mom was carrying out my dad’s final wishes and that California had all kinds of rules about throwing trash into the ocean, anyway. Never mind that my mom took care of everything, and that all my grandmother had to do was show up. Even if it had been a perfect day, I’m sure my grandmother would’ve found fault in something. She and my mom didn’t exactly get along, and after the divorce, she hadn’t been too fond of me, either.

“It’s still terrible,” Ally said with a sniff, “even if the visual is a little funny.”

At this, we all laughed, earning us stern looks from some of the adults nearby. This only made us laugh harder.

“When are you heading back to school, Pete?” Jake said after we’d composed ourselves. “You go to Northwestern, right?”

“Yeah. I’m leaving late tonight.” He stretched out his legs in front of him and crossed his ankles. “Catching a red-eye. I wanted to stay through the weekend, but I’ve got an econ test on Monday I couldn’t reschedule and a biology lab I can’t miss.”

Ally wrinkled her nose. “Yuck.”

“It’s fine,” Pete said. “My dad sprung for first class. I’ll probably sleep the whole way.”

“No, I meant the bio lab.” She shuddered. “I hate biology.”

Conversation drifted to school, with Ally and Bianca peppering my cousin with questions about college life and Finn inquiring about research opportunities. Jake squeezed my hand again, and only then did I realize he’d been holding it the whole time.

“So, is Finn ditching practice, or…?” I said, extracting my hand from his to stretch my fingers.

“There’s a game tonight, but I promised I’d get him back in time for it.” He smiled. “I maybe kind of guilted him into coming.”

I nodded. Finn was one of two sophomores on the varsity team, and he took his spot on the roster almost as seriously as he took his grade point average. After-school sightings were rare when there was practice, and even more so on game days.

“Thanks for that,” I said. “And for bringing everyone over.”

He lifted his shoulder in a half-shrug. “I needed to drop off your books and stuff for homework, anyway.”

“It’s all up on the portal,” I reminded him.

“Yes,” he said, “but I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised at the careful notes I took for biology.”

I raised my eyebrows, impressed. “This I’ve got to see.”

Ally cleared her throat. “Hey, Jake,” she said. “I don’t want to interrupt your little whatever or anything, but I need to get back to school for rehearsal.”

“I need to get to warm-ups, too,” Finn said, his eyes downcast. “Let Coach yell at me and get it over with.”

Bianca pocketed her phone and got to her feet. “Don’t worry about it,” she told him. “Tim said he and Brady covered for you. You’ll still start tonight.”

I rose to my feet to walk my friends outside. After some hasty good-byes, Jake pulled me into a huge hug.

“I’ll be around later,” he said into my hair. “If they let you out, I mean. I know you get restless and stuff.”

“Ugh. I feel like I’ve been cooped up forever.”

“Oh, before I forget.” He reached into his back pocket as he released me and handed me a smushed envelope. “From Clover.”

I looked down at it, and my stomach twisted into a knot. “When did you see her?”

“Last night.” He toyed with his keys, spinning them around his finger. “She said she’s really sorry, and if you need anything….”

“Yeah.” I forced a smile. “Tell her ‘thanks.’ I’m sure you’ll see her before I do.”

“Sure.” He hesitated for a second, gave me a quick peck on the cheek, and then got into his car. I waved to them from the driveway as he pulled away.

“When did you guys get together?” Pete said when I walked back into the house.

“Who?”

“You and Jake.”

“We’re not.”

He didn’t say anything, but he stared as though he was studying my face or something.

Jake hadn’t been kidding when he told Clover that Pete was the only family member I liked. That fact was the only thing keeping me in the same room as him; I hadn’t tolerated personal questions from anyone else. Pete was my only cousin and, not counting Brady, the closest thing I had to an older brother. We could pass for siblings, too, though he’d been lucky enough to avoid getting the white-hair birthmark.

“What?” I demanded.

“Nothing.” He busied himself picking up the cups and napkins my friends had left behind. I watched him stack them in neat piles, and my annoyance grew.

“Then why are you asking?”

Pete didn’t look up. “He just seems like he’s into you.”

“Jake?” I was incredulous. “No. No way.” I plopped down onto the sofa and looked at the envelope in my hands. “We’re just really good friends.”

He glanced at me, a skeptical look on his face. “Okay.”

I started to say something but stopped myself. I wanted to know why Pete thought Jake liked me, because if Pete was right, it didn’t make any sense for Jake to be spending as much time with Clover as he had been. But I knew he was wrong about the first, and I didn’t know why I cared about the second, so I left my questions unasked.

“Are you going to open that?” he said with a nod toward the envelope.

I handed it to him. “I’m sure it’s just another sympathy card.”

He tore it open and pulled out its contents. “Oh, how nice. It’s from someone named Clover.”

“That’s Jake’s friend.”

I must have involuntarily sneered when I said that because his eyebrows shot up. “Friend? Or, like, friend?”

“Friend,” I replied. “I think.” I waved away his question with a flick of my wrist. “Anyway, it’s like, whatever.”

Pete pursed his lips like he was trying not to smile, resulting in a weird, lopsided smirk. “If you say so.”

“Why are you so interested in my high school drama, anyway, college man?”

He sat on the armrest on the other side of the couch and looked at me, brown eyes so similar to my own staring into mine. “I like Jake.” He grinned. “He’s good at keeping you in line.”

I huffed and gave him my best impersonation of my mom’s I’m-not-impressed look. “Don’t you have an econ midterm to study for or something?”

He shook his head. “Not a midterm. Just a test. And anyway, this is way more interesting.” He flashed a toothy smile.

“You’re obnoxious,” I said with a frown.

“And you’re perceptive.” He tilted his head as if in thought before he laughed and added, “Wait. No, you’re really not.”

I narrowed my eyes at him. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“If you don’t know, my dear cousin, that only proves my point.”