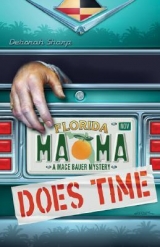

Текст книги "Mama Does Time"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Иронические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

“Easy for you to say, Miss Five-Foot-Ten.’’ She put her foot up on the dashboard to admire her lemon-hued shoe. “These are ridiculously uncomfortable. But haven’t you ever had a shoe that you loved just for the way it looks, Mace?’’

I ran mentally through my footwear inventory: leather ropers for riding, waterproof boots for work, sneakers or loafers for any other occasion.

“Nope. Can’t say that I have.’’ We passed Pete’s Pawn, with its roadkill armadillo sign. “Now, are we agreed that it’s not too much trouble for me to drive you what’s now three remaining blocks to work?’’

She straightened herself in the seat; her hair barely grazed the headrest. “I’m just trying to be considerate, Mace. You don’t need to get snippy.’’

“I could use some of that consideration the next time Cousin Whatever-her-name-is flies in to visit, and you volunteer me to pick her up at the airport.’’

She crossed her arms over her chest and stared out the windshield.

All of a sudden she reached out, turned down the radio, and yelled, “Stop! Stop right there, Mace. Stop the car!’’

“Mama, I can’t stop. I’m doing forty miles an hour. I’ve got cars in front of me and cars in back of me.’’

No wonder she had that fender-bender that started everything at the Dairy Queen.

“Okay, slow down, then. That next street there, with the used car for sale on the corner? That’s Emma Jean’s street. I remember from one time Sally and I gave her a ride from bingo.’’

As we approached, I read the street sign out loud: “Lofton Road.’’

“That’s it, Mace.’’ She leaned forward, peering out the windshield. “Let’s drive by to see if she’s okay.’’

I downshifted to take the corner.

“I’m worried about her, Mace. She sure didn’t seem right when she was swinging that tire iron at church.’’

Who would?

“There it is, Mace. The blue one. About half way down, on the left.’’

I slowed, and turned into Emma Jean’s driveway. Her cat-shaped mailbox was painted in Siamese colors. The cat’s black-tipped tail was the flag, which was flipped up straight.

I continued up the drive, noting a gaggle of yard gnomes. The rose bushes needed attention. Only the most dedicated gardeners can grow roses in the Florida heat and mucky soil around Lake Okeechobee. Judging from the mold-spotted leaves and sparse blooms, Emma Jean lacked the necessary dedication.

There was no car in the open, metal-roofed carport. I pulled in and parked. Mama and I got out.

The sun had faded the house’s blue paint almost gray. The window curtains were drawn. Her screen door was shut, as was the solid wooden door behind that. Pink and white impatiens wilted in a pot on her porch. Mama leaned over to feel the soil. Shaking her head, she picked up a watering can and poured the contents on the flowers.

I knocked at the door. No answer. I pounded.

“Emma Jean? Are you there, darlin’?’’ Mama called at the window.

“Well, we know she was here fairly recently,’’ I said. “If that tail on her mailbox was up yesterday when the mail carrier came, he would’ve taken Emma Jean’s outgoing letters and flipped it back down.’’

Mama glanced out to the cat-shaped mailbox. “You know, I didn’t even think about that. There’s a reason you were top in your class at college, Mace.”

I opened the screen door and tried the knob on the door inside. Locked.

A Siamese cat, live, not the mailbox one, minced its way up the porch steps. It sniffed at Mama’s lemon-colored sandal, and then made a beeline to me. I’m an animal lover, but I’ve never been able to warm up to felines. And don’t the cats always know that? In a crowded room, they’ll bypass a dozen cat-lovers; ignore every outstretched hand; fail to recognize a chorus of “Here, kitty-kitty’s.’’ Then they’ll decide to make friends with me.

The cat entangled itself around my ankles, rubbing against my slacks. I lifted my boot to gently push it away. Meowing, the critter stared up with big blue eyes.

“I’ll be sneezing in about two seconds, Mama.’’ Did I mention I’m also allergic? “I’m going around to check the back.’’

The cat leapt off the porch and followed.

I looked in a big kitchen window, where the curtains were tied back. Dirty dishes sat in the sink; an afternoon Himmarshee Times was closed on the table. It had to have been there at least a day, since it was still too early for today’s delivery. The silent house looked empty, but undisturbed, like Emma Jean just ran out to do an errand.

Turning from the window, I nearly stumbled over my new best friend. The cat looked up as if to say, “Careful, Clumsy.’’

I scanned the backyard.

“Hey, what kind of car does Emma Jean drive?’’ I yelled around to the side garden, where Mama was pinching sooty leaves off the rose bushes.

“It’s a little one,’’ she shouted back. “Something foreign, like a Toyota or a Honda. Why?’’

“Because there’s a pickup parked back here, next to her shed. It’s white, and it looks old.’’

I stepped closer. The bed was rusted. It was empty, except for three crushed beer cans. I looked through the driver’s window. There wasn’t anything personal inside. Just a blue bench seat, upholstered in plastic with the stuffing showing through. Kneeling on the grass, I ran my hand over well-worn rubber tread.

“What are you doing down there, Mace?’’ Mama joined me, stepping as delicately as the cat across grass still wet with dew. Beads of water clung to the reinforced toe of her knee-high stocking.

“Nothing, really.’’ I trailed my fingers again over the tread before I stood and brushed off my pants. “I was just noticing how big the tires are on this old truck.’’

Bump-bump-bump-bump-bump-bump.

My tires thumped over the wooden bridge at Himmarshee Park. No matter how bad the day, or how much work waits, driving over the little bridge always gives me a boost. Below, dark water swirled. Above, sunlight slanted through the feathery branches of cypress trees. I inhaled, breathing in the woodsy, organic aroma of the swamp.

Newcomers crinkle their noses and complain of the rotten-egg smell. It comes about as bacteria break down dead plants and animals in the water. That allows them to be consumed by other creatures; which in turn are eaten by larger critters. And so it goes.

To me, the muck and mud of the swamp smells like life itself.

I love the outdoors, but even I’ll admit there are better spots to be in the summer. The nearest coastal breeze is an hour east. If heat stroke doesn’t get you, the mosquitoes will. And park in the full sun, and your car seat will reward you with third-degree burns upon your return. Not surprisingly, our parking lot was nearly empty.

I pulled into the shade of a clump of Sabal palms. Grabbing my purse and two plastic bags full of Ollie’s chickens, I headed in to work.

The park’s office is built of cypress, with tall windows and a wraparound porch. The designer did a good job of making the structure look like it grew up in the woods. But to me, being stuck for too long inside any kind of building anywhere still feels like a trap.

Inside, a phone was affixed to my boss’ ear. Rhonda drummed the pink-polished fingers of her free hand on the arm of her chair. When she saw me in the doorway, she flexed her hand into a yak-yak-yak sign next to the phone cradled on her shoulder.

“Yes, Ma’am. I will tell Mace you called.’’ Rhonda’s fingers hovered over the phone, ready to hang up. She leaned back again, listening. “No, as I mentioned to you, she’s had a bit of family difficulty in recent days.’’ She paused. “No, Ma’am, I don’t know what it’s like to have a panther stalking the pretty red birds that come to your bird feeder.’’

The New Jerseyite! I signaled frantically, pointing at my chest and shaking my head no, no, no. The last thing I needed was her tale of woe about what I suspected was a neighbor’s fat cat. If it was a panther, it’d be after bigger prey, like her obnoxious poodle.

I was tuckered out, mentally. All I wanted was some peace and quiet to try to make sense of recent events: The come-on by the DVD-peddling pastor. The truck at Emma Jean’s. The possible connection—beyond cigars—between Martinez and Big Sal.

I went back outside to the storage room to dump Ollie’s food in the freezer. Rhonda was just hanging up when I returned.

“You owe me.’’ She rubbed at a phone-related crick in her neck. “You owe me big.’’

She stood up to stretch. Not many women are as tall as me, but Rhonda had an inch and a half on me. Nearly six feet, she should be wearing designer clothes instead of government-uniform green. She’s as beautiful as any model, and at least three times as smart.

“I know I owe you, Rhonda. I’m taking you to dinner at the Speckled Perch when all of this is over.’’

She sat back down, a smile spreading from her mouth all the way up to her angled cheekbones. The Perch is famous for its fried hush puppies. Blessed with the metabolism of a marathon runner, Rhonda devours the round corn-meal morsels by the dozen.

“I’ll handle all your unpleasant details for dinner at the Perch, Mace.’’

“Believe me, boss, you don’t want that burden right now.’’

I sat at my desk and attacked some paperwork, separating letters and messages into Soon, Later, and Never piles. A call from a retirement home in Highlands County went into Soon. Sometimes, I’ll take an orphaned possum and a few snakes and give a talk for the old people. They get nearly as big a kick as the kids do out of seeing the animals. A request to speak about wildlife at the country club, not exactly my natural audience, I filed in Later. An invitation to attend a fashion-show? Mama must have gotten me on that mailing list. Never.

When I’d cleared enough paper to see some of the daily squares on my desk calendar, I stood up and stretched. I’d been at it for fifty-five minutes. That was long enough. I needed to breathe some outside air.

“I’m gonna take a look around the park, then hit the vending machine. Want anything?’’

Rhonda looked up from a towering pile of permit cards and requisition forms. If that was management, she could have it.

“No, thanks. Take your time. I can tell from the way you’ve been jiggling your leg that you’re itching to get outside. Say hi to your animals for me.’’

“Will do.’’

“And, Mace?’’ Rhonda’s shift to her supervisor tone stopped me with my hand on the doorknob. “If you see any visitors, please say hi to them, too. It wouldn’t hurt you to be a little friendlier to the park’s humans.’’

Some guy had complained to Rhonda that I was rude to his girlfriend. She was whining about how the brush and the bugs on the nature walk had eaten up her legs. All I said was it was plain stupid to come to the woods in short-shorts and high-heeled sandals, so what did she expect?

“Got it, Rhonda.’’ I pulled open the door. “I promise not to use the S-word, even when people are stupid.’’

Outside, I headed straight for the far corner of the park, where I keep the injured and unwanted animals. I could see Ollie on a sloped bank. He was sunbathing, with his body half in and half out of the water. I leaned over the concrete wall that encloses his pond.

“Hey, buddy,’’ I called down to the gator. “How’s it hangin’?’’

I talk to the animals. A lot. Maddie says it’s a clear sign I need more friends.

“Listen, I just put a dozen plump hens in your freezer. You’re going to be dining fine.’’

Ollie blinked his good eye.

With a brain a little bigger than a lima bean, he’s not much for conversation. I started to push myself away from the wall, when I heard a distant rustle in the brush behind me. I’ve spent a lifetime in the woods, and rarely been afraid. But something about that movement didn’t sound natural. A wild hog will crash through the undergrowth, not caring who all’s around. A deer will pass by, as quiet as a sigh. But the movement I heard sounded different: Sneaky. Stealthy. Big.

Maybe the New Jersey woman was right about that rogue panther.

I turned slowly, straining to hear the sound again so I could try to place it. The woods grow all around the animal area, close enough for the tallest hardwood trees to throw shadows across half of Ollie’s pond. A mockingbird sang. Dragonflies hummed. Whatever else was out there was silent now. I turned back to the gator.

“You didn’t hear anything, did you, buddy?’’ My voice sounded unnaturally loud and hearty, like I was trying to sell something.

Ollie wasn’t buying. He was so still, he might have been an alligator-hide duffel bag with a head. But he can move plenty fast when he’s motivated.

I peered into the dark shade of the woods. Laurel oaks lifted their branches. Air plants nestled in the crooks of the trees. All of it looked ordinary. Yet, I sensed unseen eyes watching me. A clammy rivulet of sweat worked its way past my waistband, rolling down the gully of my lower back.

Then, I heard the rustle again, nearer now. Something was moving toward me through the trees. I backed up, hard against the concrete of Ollie’s wall.

The rustle got louder. Moving faster. Coming closer.

My heart pounded. Every nerve cell screamed, “Run!’’ but I had nowhere to go.

Whatever was in those woods was in front of me. Ollie’s pond was behind. And I was frozen in between, as motionless as a rabbit in the moment before its predator strikes.

Loud, angry voices suddenly rang out from my left.

“And I say it’s this way!’’

“Is not!”

I turned from the woods. A sunburned man with a camera and a woman in a Hawaiian-print shorts-set were arguing at a fork in the trail. The debate: which path to follow for the parking lot.

I’d never been so happy to see two human visitors. My slamming heart slowed. My lungs clocked back in on the job. I gulped in a big, shuddery breath.

For the first time, the woods had seemed like a threat, not a comfort. I was afraid. That must be how my sister Marty feels all the time, I thought. I didn’t care for it much.

The rustling in the woods was fainter now, moving harmlessly away. Scanning the shadows, I saw nothing but trees and palmetto scrub. Feeling somewhat foolish, I hurried into the bright sun of the clearing.

“Hey, there! How you folks doin’?’’ I called to the tourists, as friendly as a Wal-Mart greeter. “Parking’s to the right. But why don’t y’all have a look at the alligator first? Ever seen one up close?’’

The woman started tugging on her husband’s Hawaiian shirt, dragging him at a run toward Ollie’s pond. “Oh, Hal! An alligator! Get the camera ready, honey!’’

I joined the visitors at the concrete wall. I could smell coconut-scented suntan cream.

“Where’s Bobby, Hal? He really should be here to see this,’’ the woman said.

“The last I saw, he was stalking off through the forest to get his Nintendo game out of the car.’’ Hal looked at me and shrugged. “Kids. What’re you going to do?’’

Judging by the size of his dad, whose flowered shirt could have been the tablecloth for a party of six, Bobby could be big enough to make the sounds I’d heard in the woods.

I asked, “Would your son normally stay on the nature path?’’ We’d groomed it, clearing away brush, after the woman in the tiny shorts complained her legs got scratched.

“He’s thirteen. What do you think?’’ Hal’s voice had an aggressive edge. “Bobby’s not so good with rules.’’

He held up his camera. “I’d love to get my wife in the picture, too. Is there any way Ev can climb down and get close to the alligator?’’

Rhonda’s warning about the S-word ran through my mind.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea,’’ I said evenly. “Ollie hasn’t been fed today.’’

“Oh, that’s something we could do, Hal!’’ Ev took an excited little hop up and down. “Alligators are supposed to love marshmallows. A man at the RV camp where we’re staying says one in the canal will climb right onto shore. The alligator opens his mouth, and the man just tosses in the marshmallows, one after the other.’’

No S-word. No S-word. No S-word.

“I hope your RV neighbor’s not too attached to his arm,’’ I said. “A couple of years ago, fishermen in Lakeland found the body of a man who’d been missing for a while. A gator got ’em. In the same lake, trappers killed a three-hundred-pounder. All the residents had been feeding him. That’s illegal, by the way. They opened the gator up, and there was the poor fisherman’s forearm. It was still intact, in the alligator’s stomach.’’

Ev ran a hand down her own arm, glancing nervously over the wall at Ollie.

“Alligators are wild, unpredictable creatures.” I could hear the annoyance seeping into my voice, but I plowed ahead. “You have to realize, they’re dangerous. They’re not costumed characters at Walt Disney World, ready to pose for tourist pictures.’’

“We get it, we get it.’’ Hal stuck out his chest. “We’re not stupid. You don’t need to take that high-and-mighty tone with us. You don’t have to be rude.’’

Uh-oh.

“Sorry.’’ I backpedaled. “I didn’t mean to sound nasty.’’ I flashed them a smile that would make Rhonda proud. “It’s just that people who feed alligators cause a lot of problems, both for the people and the gators. They’re naturally skittish of humans. But if someone feeds them, they learn to associate people with food.’’ We all looked down at the gator in the pool. “Missing one eye and part of a foot hasn’t done much to slow Ollie down. And it hasn’t done a thing to diminish the power of his jaws and tail. He’s here because he got a little too close for comfort on the eighteenth hole at the new Kissimmee Links country club.’’

Hal let out a low whistle. “That’s a hell of a water hazard.’’

“Did he kill someone?’’ the woman asked.

“Not yet.’’

I recited the facts I knew by heart from my lectures to the kids: Biting strength more fearsome than a lion’s; eighty razor teeth; a tail that can break a man’s—or a woman’s—leg.

Then I agreed to take a picture of the two of them leaning against the wall. I climbed onto a step stool I dragged over from the shed. With that and my height, I could angle downward to get Ollie in the background and the stupid couple in the foreground. I took four or five shots from different angles. The visitors left with all their limbs. Everybody was happy.

Being friendly is hard work.

Giving my little talk about alligators had just about erased the uneasiness I’d felt at the noise in the woods. But with the visitors gone, a twinge of fear came back. What was it moving toward me, pinning me between the woods and Ollie’s wall? Was it just the couple’s son, stomping around in a teenage sulk? Or was it something more sinister?

I decided to try to find the Nintendo-addicted Bobby, and ask him some questions. Normally, I’d cut through the woods, reducing by half a fifteen-minute walk to the parking lot. Today, I stayed in the clearing as long as possible. Then, I chose a wide, well-marked path.

The parking lot held just three vehicles in addition to the VW and Rhonda’s car. One was a burgundy Mercury, with Pennsylvania plates. A bumper sticker on the back said: My son can beat up your honor student.

I pegged that one as Hal’s car.

Another was a rental, with a Florida map and a bird-watching brochure sitting open on the front seat.

The third, a white pickup, was the only one parked in the shade. Squinting through the heat rising from the lot, I thought I recognized the black cowboy hat on the man in the driver’s seat. I quickly closed the distance to the truck.

Engrossed in a cell phone call, the driver was alone in the truck. He didn’t notice as I approached from the rear. The driver-side door was open.

“I told you I’m good for those cattle, Pete.’’ I could hear his half of the conversation. “How long have we known each other? All I’m asking for is a little more time.’’

It sounded like Jeb Ennis’ business troubles had taken a turn for the worse.

Silently, he listened to whatever Pete was saying on the other end of the line. Then he shook his head and looked like he was ready to start arguing, until he caught me from the corner of his eye. “Listen, I’m going to have to call you back, Pete.’’ He paused. “If I say I’ll do it, I’ll do it. I’ve got someone here just now.’’

He cut off the call and slipped the phone into his top pocket. His face was shiny with sweat.

“Kind of warm to be out here sitting in your truck, isn’t it?’’

“Hey, Mace. I just pulled up a little while ago. I was headed to the office to see you when my phone rang.’’ He swung his long legs out the door and stood on the asphalt lot. When he turned and leaned in the back to grab something from the truck’s cab, I saw his shirt was soaking wet and stuck to his back.

“You look like you’ve just chased a coonhound through the woods, Jeb.’’

When he straightened, he was holding a bouquet of daisies.

“Yeah, I’m sweatin’ buckets.’’ He looked embarrassed. “The AC’s out in my truck. Never happens in December, does it? It feels like a sauna in there.’’

He held out the flowers. “Anyway, these are for you. I figured I owed you an apology for being so rude at the diner. Your mama must have heard an earful after I left.’’

As I took the flowers, our hands brushed. His fingers were strong, work-callused. I fought myself over the little shiver of desire I felt.

“Daisies are your favorite, right? I remembered.’’

I couldn’t even think of the last time a man had given me flowers. I smiled my thanks. That didn’t mean I wasn’t still suspicious.

“So, you just drove up.’’ I took a couple of steps to the front of the truck and put my hand on the hood. The metal was as hot as Hades. The engine still ticked. “I had an interesting experience a little earlier this morning.’’

He raised his brows in a question.

“I felt like something was watching me from the woods by the alligator pond. Then, I heard something big coming at me through the brush.”

Jeb’s face lit up. “Was it a black bear? Remember that time we spotted that cute little cub over in Highlands County? And then its mama came on the scene, and she didn’t look near as cute.’’

I laughed. “I remember you were just as scared as me, and I almost peed my pants.’’

He looked at me, and the golden flecks in his eyes shone. “We had some good times in those days, didn’t we, Mace?’’

“Some real good times,’’ I agreed. “And a few bad.’’

He took off his hat and shifted his eyes to the ground. He ran a hand through his hair, which curled in sweaty clumps. Then he looked up at me again. “Do you think we could talk somewhere, Mace?’’

“We can. But first I have to ask you something. You wouldn’t have had any reason to be running around in the woods out here this morning, would you?’’

He cocked his head “Mace, it’s hotter than a pepper patch. The mosquitoes are as big as B-52 bombers. I can think of about twenty places off the top of my head that I’d rather be than in the woods. And that would include sitting in the chair at my dentist’s office. I told you, I just got here. The only reason I came at all is to apologize to you.’’

He slapped at his neck, then flicked a dead mosquito from his palm.

I glanced into the trees surrounding the parking lot. Nothing but the insects stirred.

“It’s just that I had a …’’

My voice trailed off as I tried to figure out how, without sounding weak or crazy, to explain what I’d had. The sense of threat. The paralyzing fear. After all, it was just some rustling in the brush.

“You know what, Jeb? It’s no big deal.’’ I held up the flowers. “Let’s head to the office, where I can get these in some water. We can sit out on a bench in the breezeway. At least there’s shade, and ceiling fans to keep us cool.’’

He put his hat back on. “Give me a minute to throw something over the feed I’ve got in the truck. I don’t want it to get wet if it rains.’’

I stepped aside to let him get to the truck’s bed. I took the opportunity to admire the view as Jeb leaned over to secure a tarp. His sweaty shirt was tucked tautly into his narrow waist. The W’s on the back pockets of his Wrangler jeans lay just right. My eyes traveled all the way from his well-shaped rear, down his legs, to the heels of his dusty cowboy boots.

That’s when I noticed something small clinging to the bottom of his pants leg. In the back, where it’d be hard to see, a burr from the woods’ brushy undergrowth was stuck to the fabric of Jeb’s boot-cut jeans.

“What the hell is this?’’ I leaned over and plucked the burr from Jeb’s pant leg. Pinching it between my thumb and forefinger, I thrust it inches from his face.

“How should I know, Mace? You know plants a lot better than I do. Why don’t you look it up in a plant book?’’

“It’s a beggar’s tick, Jeb. And I don’t mean, What is it? I mean, How in the hell did it come to be hitching a ride on your Wranglers?’’

He cocked his boot up to examine the back of his pant leg. Then he repeated it with the other leg. “I thought I got all of those off before I headed over here to see you. I worked this morning, but I did clean up. Not that you’d be able to tell it from the stink of me, after I drove all the way from Wauchula in my sweat box of a truck.’’

I tucked the beggar’s tick into the pocket of my work pants. You never know what you might need as evidence.

“What are you so freaked out about anyway? Is that from some nasty plant you don’t want taking hold here at Himmarshee Park?” His eyebrows raised in a question. And then, as he realized what I was implying, they V-ed down to a frown. “You’re not serious, Mace.’’

“As serious as a heart attack.’’ I took a step back, my hands on my hips. “Which is what I almost had this morning, when I was convinced something in those woods was stalking me. Now I find a burr from the brush on a man who claimed he’d rather be anywhere else than out stomping through some swampy woods.’’

“You’ve lost your mind.’’ He inched away, like he was afraid to catch crazy from me. “Your mama getting arrested for murder has sent you clear round the bend.’’ Staring at me, he shook his head. “Do you think Himmarshee Park is the only place in Florida with brush?’’

He waited for an answer. I didn’t give him one, staring off into the trees.

“Well, it’s not.’’ Jeb answered his own question. “I was tearing through it on my own property early this morning when a calf got tangled up. He ran off, trailing some barbed wire into the woods.’’

I thought about that for a moment. It seemed logical. I was beginning to feel stupid.

“Are you gonna suspect me of everything, just because I made one of the biggest mistakes of my life when we were kids? How many times can I say I’m sorry I lied to you? I’m sorry I cheated on you. I was young and stupid. I didn’t know how to handle the attention from the girls who hang around the rodeo.’’

He put a hand on my wrist. My skin felt hot where he touched it, and it wasn’t just the outside temperature.

“Look at me, Mace.’’

I slowly shifted my gaze from the tree line to his face. He was staring into my eyes. His hand still burned a palm print around my wrist.

“Sorry,’’ I mumbled.

Jeb cupped his other hand to his ear. “Can you speak up a little? I didn’t quite hear that.’’

“I said I’m sorry.’’ I shook off his hand. “This case has got me as skittish as a colt in a pasture full of snakes.’’

I looked down to where he’d held my wrist. I was surprised to see no outward sign of how his touch had affected me. But I did notice the daisies were starting to wilt. “Why don’t we go on in and get out of this oven?’’ I said.

I led the way across the lot and onto a wood-chip trail. We don’t waste much in Himmarshee. If a hurricane or lightning storm takes down a tree, workers with chain saws cut it up, feed it into a chipper, and truck in the chips for pathways. Jeb and I turned at the fork, heading away from Ollie’s pool and toward the office.

“Look at that,’’ I whispered. As we rounded a bend near Himmarshee Creek, a great blue heron startled into flight. The woods were so quiet; we heard his big wings beating the heavy air.

At the office, I went inside to put the daisies into water. Jeb stopped to buy sodas at the vending machine. He didn’t need to ask what I liked. A Coke for me; an orange drink for him. He was just settling onto a bench in the shady breezeway when I returned to join him.

“When did you find out about Mama getting tossed in jail?’’ I asked, as I popped the top on my can of Coke.

“I already knew that night at the diner, Mace. One of my hands at the ranch dates a gal who works at the Dairy Queen. I didn’t let on when you told me. I didn’t want to embarrass you. And I didn’t think it’d be too nice to greet your mama after ten years by saying, ‘Glad to hear you’re out of the slammer, Ma’am.’ ’’

He took a long slug from his soda. Staring at the spot where his lips met the can, I felt memory waves wash over me. Lying on three folded blankets in the bed of his truck, watching shooting stars. The feel of his lips on mine, soft yet insistent. My first time, and how Jeb kissed away the tears that came from the realization that I wasn’t a virgin anymore.

“Can I ask you something, Mace?’’

I nodded, hoping it wouldn’t be “What are you thinking?’’

Jeb said, “They let your mama out of jail. But you said the case is making you nuts. Why are you still involved?’’

Good question, I thought.

“Well, for one thing, someone has made it pretty clear they don’t want us looking into Jim Albert’s murder.’’ I told him about Mama’s stuffed dog, and about my close call in the canal.

“That sounds pretty dangerous. Yet you’re still fooling around, trying to figure out whodunnit.’’

“You’ve known me a long time, Jeb. Tell me I can’t do something, and that’s exactly what I want to do. Besides, Mama’s name hasn’t been cleared.’’ I outlined how her fellow church-goers had stared and whispered. Martinez might be busy right now, I said, trying to build a stronger case against her. I didn’t mention I’d tried to steer the detective off my mother by telling him about Jeb’s troubles with Jim Albert.

I watched a drop of condensation roll off my can and onto my thigh.

“I also want to know how Mama’s boyfriend figures in, Jeb. What if he’s responsible? Mama could be in danger. I’d toss myself into Ollie the alligator’s pond if something happens to her, and I could have prevented it.’’

“It just seems like you’re putting a lot of pressure on yourself, Mace.’’

“I’m not alone. Both my sisters are involved. We’re all trying to find the real murderer. You don’t think Maddie would let anything happen to me, do you?’’