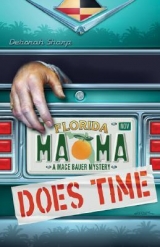

Текст книги "Mama Does Time"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Иронические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Hurricane Janet took a terrible toll on Jack and Donna Warner of Basinger. Their three-year-old daughter, Ashley, died when the storm destroyed their house in June. The child was struck on the head by a roof beam torn off in the hurricane’s 100-mph winds.

Now, Himmarshee police are looking into whether the Warners and other families struck by the June storm have been victimized again.

Almost $5,000 is missing from a fund designated to help hurricane victims rebuild, according to sources at First Florida Bank. Himmarshee Police Chief Ben Johnson confirmed that money is gone, but would not specify a sum.

“There are some discrepancies in the bank account,’’ Johnson said. “We’re investigating the matter. We’re still hoping there’s a reasonable explanation. I hate to think anyone in Himmarshee would steal from people who’ve already been hurt so much.’’

The fund was begun by members of the Abundant Hope and Charity Chapel. Phone messages left on the church’s answering machine were not returned. The Rev. Bob Dixon, pastor at the church, could not be reached for comment.

Johnson declined to say whether any arrests are imminent.

I was staring at the newspaper, picking my lower jaw off the table, when Mama walked up. “Mace, you won’t believe what happened at Hair Today.’’ She pulled out a chair and collapsed with a dramatic sigh.

I slid the Times onto her map-of-Florida placemat, right over our red star above Lake Okeechobee. “Before you say a word, read that.’’ I tapped the headline with my index finger.

“Well, it’s about Delilah,’’ Mama started in, ignoring me as usual.

“Not another peep.’’ I grabbed her glasses from her purse and slapped them in her hand. “Go ahead. Read.’’

Mama clucked her tongue at the part about the Warners’ little girl. Her eyebrows shot up when she came to the missing money. At the end, her hand flew to her throat.

“Jesus H. Christ on a crutch!”

Charlene, clearing plates off an adjacent table, shot a surprised look over her shoulder.

“Sorry, darlin’.’’ Mama slapped a hand over her mouth. Then she leaned in and whispered through her fingers. “This is bad, Mace.’’

“I know it, Mama.’’

“It’s real, real bad. I was going to tell you that Pastor Bob never did come back for poor Delilah today. That’s why I’m so late. I stayed there with her. First, she was embarrassed. Then she got irritated at him for keeping her waiting. Finally, she got plain worried. The woman was in tears, Mace. She kept calling and calling him on his cell phone.’’

“No answer?’’

“Straight to voice mail. She phoned the church office, thinking he might be there. The beep on the answering machine went on forever. Delilah said that meant there were lots of messages. She couldn’t figure out why.’’

I tapped the paper again. “I’ve got a pretty good idea, after reading that.’’

“Finally, D’Vora offered to run her home. They dropped me off here on the way.’’

We both looked down at the Times.

“What do you think it means, Mace?’’

“I’m not sure. But I aim to find out. A lot of little strands have been unraveling all around Jim Albert’s murder. Money seems like a common thread. Now, here comes another string, leading straight to Pastor Bob Dixon.’’

___

“Delilah?’’ Mama pounded for the fourth time on the Dixons’ front door. “Let us in, honey. We just want to help.’’

We called D’Vora to find out where she’d dropped Delilah. I was proud of Mama. She hadn’t given away a word, just said she had something for Delilah she’d forgotten to give her.

The house was modest, a one-story white stucco on a quiet street, only a couple of miles from the church. There was no car in the driveway. A wooden welcome sign with a clump of silk flowers in yellow and white decorated a front door painted robin’s-egg blue. A plaster cross hung beside the door, with a passage from the book of Joshua engraved in fancy letters: As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.

I doubt the Lord would consider it in His service to rip off hurricane victims.

Mama kept pounding. Finally, heavy steps sounded behind the door. Pale blue curtains rustled at the window.

“Honey, we don’t mean you a bit of harm. We figured you’d need someone to talk to. Now, open up,’’ Mama ordered through the door.

The door cracked. A thick pair of eyeglasses and one red-rimmed eye peeked out. Delilah opened up a fraction wider and looked both ways. Her face was a mess, but her hair looked terrific. Betty had done a remarkable job.

“No reporters?’’

“Not a one,’’ Mama said.

“That man from the Himmarshee Times has been calling ever since I got home. I finally answered and told him I have no idea what he’s talking about. Bob handled all the money for the church and the house.’’

“May we come in?’’ I asked. “The neighbors will wonder why we’re talking to a door.’’

She stood aside to let us by, then turned and stalked away. “Suit yourselves.’’ Her tone was hard. “I suppose you’ve come to gloat.’’

The newspaper was on Delilah’s otherwise spotless carpet, open on the hurricane story.

“We’re not gloating,’’ Mama said. “We’re women, just like you. We feel for what you’re going through.’’

A sniffle came from Delilah’s direction. The hard shell was beginning to crack. “Would you like a cup of coffee?’’ she asked in a softer voice. “I was just about to make myself a pot.’’

Before I could scream “No More Coffee!” Mama said, “We’d love a cup. That’s very nice of you, Delilah.’’

As she busied herself preparing the pot, Mama and I took seats at the table. Images of butterflies were everywhere. They fluttered across the curtains. They danced on the coffee cups. They formed a butterfly bouquet in a vase on the table. The way Delilah’s words stung, she was more like a wasp than a butterfly. And she was big, like a hawk. Yet, deep inside, she seemed to identify with the most fragile of winged creatures.

Or, maybe she just liked butterflies.

She poured a coffee for each of us. My bladder tightened in protest.

“I may as well get right to it, Ms. Dixon. Mama and I read the story in this afternoon’s Times. Is it true?’’

She looked into her coffee cup, avoiding our eyes. A tear plopped onto the table, and her shoulders began to shake.

“I don’t know if the newspaper has it right or not.’’ Sobbing, she took off her glasses and slipped them into a pocket on her housedress. “Like I said, Bob takes care of all the financial matters. But …’’ she stopped, raising her light brown eyes to ours. Hers were filled with tears.

“But what, honey?’’ Mama stroked Delilah’s thick arm.

“He’s definitely gu … guh … gooonnnne.’’ More sobs. “He cleaned out all his drawers and his side of the closet. He even took the envelope the cashier at the grocery gave me yesterday. It had fifty-six dollars the store collected for the hurricane fund. I left it on the hall table until Bob could get to the ba … buh … baaaank,’’ she wailed.

Mama pulled a boysenberry-colored handkerchief from her purse. She patted and murmured. I envied her ability to let bygones go, comforting the same woman who’d razzed her about her jail stint. I hold onto a grudge tighter than Midas with his money. I’m not saying I’m proud of it.

Her sobs finally subsided into hiccups. “The whole thing is my fault.’’

“Why?’’ I asked.

“Don’t be silly.’’ Mama jumped immediately to Delilah’s defense. “What could you possibly have done to make your husband do an awful thing like this?’’

I said nothing, withholding judgment until I heard her answer.

“I don’t think this would have happened if I hadn’t pushed Bob beyond his limit. He’d already been under a lot of stress because his plans to grow his ministry weren’t working. And then I come along and …’’ she couldn’t finish the sentence. “I’m so ashamed to admit it …’’

“Honey, there’s not a one of us pure enough to cast a stone,’’ Mama reassured her. “We’ve all done things we’re sorry for. Go on and say what you need to say.’’ She brushed the well-coiffed hair from Delilah’s forehead.

“It’s all because of me that Bob wasn’t thinking straight.’’ Delilah fiddled with her teaspoon. “You know that woman Emma Jean came into the church shouting about? The woman who was having an affair with her man?’’

We nodded.

“Well, that was me. Lord forgive me, I was cheating on my husband with Jim Albert.’’

Mama actually gasped. I kept my mouth shut, processing Delilah’s confession.

She was silent, too. Staring out the window, she traced the wings of a butterfly on her coffee cup. Maybe she wished she were outside, floating peacefully from flower to flower on her trellis of Confederate jasmine.

“Why didn’t you say anything the night Emma Jean came to Abundant Hope?’’ I asked.

Her head snapped around, and I thought for a moment she was going to slap me. She might be hurt and humiliated, but there was still a slice of mean in Delilah Dixon.

“What should I have said? ‘Excuse me, everyone. I’m the wicked woman Emma Jean is yelling about.’ I couldn’t do that. I’m the pastor’s wife. I’m supposed to be a model of propriety.’’

I wasn’t letting her off that easy. “You just stood there, as each of those fine churchgoers looked with suspicion from woman to woman.’’ I flashed on the pretty soprano. The way Emma Jean had stared, even I’d suspected her. “That’s not right. It’s not Christian.’’

Mama put a warning hand on my wrist. “Hush, Mace. Delilah knows she’s done wrong. But she’s got all sorts of trouble right now. Her husband’s gone. So is the hurricane money. She doesn’t need you piling on.’’

Delilah got up for the coffee pot. She raised her eyebrows to me. Not unless you want me to pee right here on the butterfly-covered cushion of your kitchen chair, I thought. But I just smiled and shook my head.

“No, Rosalee. Your daughter’s absolutely right. I wanted to confess. I really did. But I simply couldn’t get out the words that night in front of everyone. I prayed and prayed about it, asking God to help me do the right thing. I’d decided to ask Emma Jean for her forgiveness, but she vanished before I could do it.’’

We sat, listening to the tick of a butterfly clock over the kitchen sink. A Monarch hovered at twelve o’clock; a Swallowtail at six. As I studied the specimens for each hour, a mini lepidopterology course, Mama eyed a store-bought package of pecan cookies on the counter.

“Delilah, honey?’’ She licked her lips. “Would you mind if I took a couple of those cookies? I never had lunch today.’’

She glanced over her shoulder at the bag, but made no move to get up. She seemed completely defeated. “Of course, Rosalee. Help yourself.’’

Mama started struggling with the indestructible packaging. She put it between her knees and tugged. She turned it this way and that, trying to find a tab to rip. Delilah took the cookies without thinking, as if she was accustomed to being the one in the house who opens lids and unsticks drawers. The tendons in her forearms flexed like steel cables as she forced open the bag.

“You’re awfully muscular, Delilah. Do you exercise a lot?’’ I asked.

“My heavens, no!’’ A tiny smile creased her mouth. “Wouldn’t I be a sight in a leotard?’’

Delilah spread her anvil-sized hands, staring at them as if they belonged to someone else. “No, I never needed to exercise. I’ve always been strong. My father was German and my mother Norwegian. They were both from hardy, peasant stock. All my brothers and sisters were big, too. But I was the biggest. My father used to call me Schweinchen, which means piglet in German. He meant it as an endearment.’’

“That’s a nice memory,’’ Mama said.

“Not really. The kids at school took my father’s nickname for me and turned it into ‘pig fart.’’’

I pictured a heavy little girl in glasses, ridiculed and teased. Sympathy for Delilah was beginning to come easier.

But then I looked again at those big hands, dwarfing the butterfly mug as if it were a doll’s teacup. What kind of damage could they do? Jim Albert was dead, tossed like a sack of garbage into Mama’s trunk. First Emma Jean vanished. And now Delilah’s husband had, too. Several of those unraveling strands seemed to start with the woman sitting across the table from Mama and me.

“Emma Jean called me the night she disappeared,’’ I said, watching carefully for Delilah’s reaction. “She knew who Jim was cheating with. She told me she was going to confront the other woman. So, you’re saying the confrontation never happened?’’

Delilah continued to stare at the table. My question hung in the air. Finally, she looked up with narrowed eyes. “That’s just what I’m saying.’’ She filed the sharp edge from her voice. “Mace, I don’t know who Emma Jean believed was the other woman. Maybe there was more than one. I do know I cheated with her boyfriend. I asked God and my husband to forgive me. I was going to ask her, too, even though I was terrified after seeing her waving that tire iron.’’

“You’ve just been telling us how strong you are. Why would you be scared?’’ I said.

“Emma Jean’s nearly as big as I am. She’s ten years younger. If there was ever going to be a confrontation, I don’t know that I’d come out ahead.’’

I looked over at Mama. She was munching on her fourth pecan cookie, looking thoughtful.

“Why’d you do it, Delilah?’’ she finally said.

I had no idea what she was talking about, and I’m used to deciphering Mama Code. Delilah’s eyebrows were so tightly knit she looked like she was trying to do higher math.

Mama clarified. “I mean, why’d you cheat on your husband in the first place?’’

Delilah sighed. Was it sadness? Or was it relief Mama was only asking about sex?

“I only did it once, you know?’’ She touched the tight, beauty-shop waves in her hair. They sprang back. “I’d gone to the drive-thru to pick up some sodas for the youth group’s pizza night. Jim was there. He complimented me; told me how nice I looked in blue flowers. I looked like a pretty flower myself, he told me.’’

If Delilah had been wearing the same floral dress we’d seen her in at church, Jim Albert had been a liar as well as a weasel.

“I couldn’t remember when a man last acted with me that way. I liked it. It made me feel young again.’’ She lifted her eyes to us. I thought I saw the passage of sad and lonely years reflected there. “You may not know it by the way Bob acts in public, but I’ve had to put up with a lot from my husband. Bob’s a serial cheater.’’

I shot a quick glance at Mama. Both of us remembered the creepy scenes with Pastor Bob in his office and at Hair Today.

“It’s humiliating.’’ Delilah dabbed at her eyes with Mama’s handkerchief.

I was back to feeling sorry for her.

“It got so bad at our last church, the board forced Bob out. We prayed and prayed about it. He begged me to forgive him. Again. Things were good for a while, but then I saw the signs he was starting to slip. Again. And then, one night, Bob never came home at all. The next day, I met Jim Albert for the first time at the Booze ‘n’ Breeze.’’

“You’d had all you could take.’’ Mama patted Delilah’s hand, perhaps thinking of all those nights she waited to hear the key turn in the lock with Husband Number 2.

“That’s right, Rosalee. And when Jim Albert started flirting, I was ripe. I still didn’t know who Bob was playing around with, but I was certain he was playing around. Again. A couple of days later, I went back to the drive-thru, and there was Jim. I didn’t have the first feeling for him. A man with a diamond pinky ring, can you imagine?’’

She was married to a man with whitened teeth and clear-polished fingernails. Myself, I didn’t see how a pinky ring was that much worse.

“He told me he had some special cartons of soda at discount prices in the back. I knew full well that was malarkey. But I didn’t care. He left this girl with funny braids in charge.’’

I flashed on Linda-Ann, the slacker clerk.

“We went to his office and he locked the door.’’ Delilah traced the rim of her butterfly cup. “We did it right there, on a stained couch of brown-and-white plaid that smelled like stale cigarettes. I remember looking at a bare lightbulb on the ceiling. A Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders poster hung on the wall. The poster was crooked, and the beige paint was peeling.’’

Tears dropped as dark spots on the front of Delilah’s pink housedress.

“I didn’t feel a thing.’’ She hid her face in the lacy handkerchief.

Mama stroked her hair. “Let it all out, honey.’’

Something had been niggling at me throughout Delilah’s confession. I thought and thought. Her sobs slowed to whimpers. Finally, it came to me.

“Ms. Dixon, did you say you asked your husband to forgive you?’’

She lifted her face from the handkerchief. “Oh, yes. I got down on my knees and begged. But Bob was furious. Angrier than I’ve ever seen him. I was actually frightened he’d hurt me. And I never felt that way about him or any other man.’’

“He must have gotten over it,’’ Mama said. “He seemed sweeter than strawberry pie at the beauty parlor.’’

Delilah blew her nose. Mama’s hankie wasn’t up to the challenge. I tore two squares from the paper towel roll and handed them over.

She spoke from behind a wad of towel. Her voice was bitter. “Oh, Bob’s a very good actor. He’s had a lot of practice, pretending he isn’t cheating.’’

“So he was angry you’d been with Jim Albert?’’ I asked.

She nodded, her eyes wide. “When he stormed out of the house that night, he was in an absolute rage.’’

“Delilah, honey?’’ Mama and I exchanged a look. “Did Pastor Bob own a gun?’’

Maddie taped crepe paper to the wall at the VFW lodge. The garland was as straight as the center line on a flat stretch of Florida highway. Marty followed behind—unsticking the tape, draping the paper, and tying it into festive bows.

“Hmph.’’ Maddie looked over her shoulder. “You’ve got it looking like a fancy birthday cake, Marty.’’

“That’s kind of the point, Maddie.’’ I was supervising. “It is a party, after all. It’s supposed to look pretty.’’

“I’d hardly call a pot-luck prayer breakfast a party. What are they going to do? Put top hats on the biscuits?’’

Marty made a final paper loop-de-loop. “For once in your life, could you not criticize everything, Maddie?’’ She tied a purple bow onto a gold streamer, keeping her eyes on her hands. “This is a big deal for Mama, even if it’s not exactly your style.’’

I was afraid Maddie was going to toss the heavy tape dispenser at Marty’s head. Ever since that promotion, our little sister had become more emboldened about speaking her mind.

“Hmph,’’ Maddie huffed, as if she had plenty to say. But when she looked at Marty, tongue peeking sweetly from the corner of her mouth in concentration, Maddie put down her would-be weapon.

“Explain to me again why we’re here while Mama’s off cavorting with her obnoxious boyfriend?’’ Maddie said.

“Fiancé,’’ I corrected. “They’re going to be married, whether you like it or not.’’

With all the excitement over going to jail and getting engaged, Mama had almost forgotten about her church’s annual Save a Sinner breakfast. That’s not the official name. It’s shorthand for my sisters and me. The members of Abundant Hope invite as many non-members as they can, plying them with a lavish, Southern-style breakfast. All the church ladies and a few of the men bring their specialties. The hope is guests will be so caught up with food and fellowship, they’ll commit themselves to the Lord between the homemade biscuits and the egg-and-sausage casseroles.

Mama remembered at the last minute she was supposed to be in charge of decorations. Meanwhile, Sal had made dinner reservations at the new country club. He wanted her to meet his golfing buddies and their wives. Since it was another opportunity to show off her engagement ring, Mama hadn’t hesitated. Which is how my sisters and I wound up spending our Friday night at the Veterans of Foreign Wars lodge, picking up the decorating ball that Mama had dropped.

I stood back to admire our handiwork.

A Welcome banner hung across the stage. Jesus held out a beckoning hand on a color poster, with John 3:16 inscribed in big type across the bottom. The churchgoers know the Bible verse by heart. But, for the less faithful, there was a cheat sheet beside the poster:

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

White plastic cloths covered all the tables; a vase of silk irises and marigolds decorated each one. Purple and gold are the school colors for Himmarshee High. Supplies in those shades are always left over, so they get used for just about every party in town, except funerals.

“Well, sisters, it looks as good as it’s gonna look.’’ I said. “Let’s eat.’’

I opened the box of pizza we’d ordered. We all took a seat at the one table we hadn’t decorated. In the morning, it would be crowded with platters of grits and red-eye gravy; biscuits and fruit butter; country ham and sweet potato pancakes.

Maddie helped herself to a pizza slice from the pepperoni-and-sausage side. “What I don’t understand is how they think they can still throw this big church shindig. Everyone knows the pastor vamoosed after knocking off his wife’s lover and stealing from those poor hurricane victims.’’

“Allegedly, Maddie.’’ Marty lifted out a piece from the cheese-only side. “Allegedly. No one has talked to the man, so we don’t know Pastor Bob’s side of the story.’’ She took a tiny bite. “Haven’t you ever heard of the concept ‘innocent until proven guilty?’ ’’

What were they putting in the water at the Himmarshee Library? Our mild-mannered sister was becoming a spitfire. I spoke before Maddie could come back with something mean.

“Well, he sure looks guilty. Delilah couldn’t find his gun when Mama and I were at the house this afternoon. But she found the paperwork on it. It’s a revolver, a Smith & Wesson.”

Maddie slid the box to her side of the table. “What’d Detective Martinez say?’’ She rolled up her second slice like a burrito and chomped off the end.

“You know how he is,’’ I said. “Played it close to the vest, as usual. But he perked right up when I told him Pastor Bob owned a .38.’’

“Is that the kind of gun that killed Jim Albert?’’ Marty asked.

“Martinez wouldn’t say. I tried calling Henry, but he left his law office early. He’s taking the kids to Disney, and you know what that means.’’

“A thousand rides on Space Mountain and no pesky cell phone,’’ Maddie said.

“Anyway, Martinez was awfully interested in the Dixons’ marital problems and the missing money. He planned to talk to Delilah today. Mama and I offered to be there, but she turned us down. I think it gave her something else to focus on besides worrying how everyone will react to her tomorrow at the prayer breakfast.’’

“Poor Delilah.’’ Marty nibbled on a sliver of crust. She stared at us, blue eyes immense and serious in her small face. “Have y’all considered how many questions are still unanswered? For example, what happened to Emma Jean?’’

Maddie chose her third slice from Marty’s meatless side. “Maybe she found out Pastor Bob killed her boyfriend. He had to kill her, too, before she told the police.’’

I remembered how out-of-control Emma Jean had been at Abundant Hope; how distraught she’d sounded when she called me on the phone.

“Remember what Mama told us about Emma Jean’s little boy going missing all those years ago?’’ I said. “Maybe she couldn’t take losing another loved one. Maybe she walked into Taylor Creek and just kept walking until she drowned.’’

“Maybe a moccasin bit her.’’ Marty shuddered.

“Then why haven’t they found a body?’’ Maddie asked.

“She could be caught up under a fallen log,’’ I said. “A gator could’ve dragged her off. You know how the swamps are, Maddie. A lot can stay hidden in there.’’

“You’re the swamp rat, Mace. I stay out of that mess.’’ She took a compact from her purse and swiped at a tomato sauce smear on her chin. “Anyway, there’s another person whose behavior has seemed mighty suspicious. Sal Provenza. Mama’s Yankee fiancé.’’ She snapped shut her compact like an exclamation point.

Marty, studying a cartoon Italian chef on the pizza box, said nothing.

“It is strange how he won’t reveal anything about his life in New York before he retired to Himmarshee,’’ I said. “But all of a sudden Mama seems convinced he’s on the up-and-up. Do you think he told her something to put her mind at ease; something she hasn’t told us?’’

“Ha!’’ Maddie slapped the table, causing the pizza box—and Marty—to jump. “That’s a good one, Mace,’’ she said. “Asking Mama to keep a secret is like asking a sieve to hold water.’’

Our little sister remained silent, eyes cast down to the napkin she was shredding.

“Well, Martinez seems to have shifted from thinking Sal is Public Enemy Number One,’’ I said. “Sal may be okay, if we can trust Martinez. And I’m not saying for sure that I do.’’

Marty lifted her face. “Of course you can trust Carlos, Mace,’’ she said. “He’s a policeman. They protect and serve. It’s an oath.’’

Maddie snorted. “Get real, Marty. Haven’t you ever heard of police corruption? The man is from Miami, after all. Maybe he and Sal were both involved with Jim Albert in something fishy. And they murdered him to take all the profits.’’

We sat quietly for a few moments, digesting our pizza and our theories.

Marty finally cleared her throat, an apologetic sound. “There is one person we haven’t mentioned, Mace.’’ Her voice was a whisper, as if by speaking negatively she might unsettle the universe. I knew right away which conversational planet she was circling.

“Jeb Ennis,’’ I said. “You can talk about him, Marty.’’

“That devil again.’’ Maddie looked like she wanted to curse Jeb and spit on the floor. “I’d be the first one to march him straight to jail. But even I have to say the pastor seems to have a better motive for the murder than Jeb Ennis does.’’

Marty’s shredded napkins were a snow bank in her lap. “He owed Jim Albert an awful lot of money, Maddie.’’

“Yes, but we don’t know about Bob Dixon, do we? He must have been financially desperate to take that hurricane money—to allegedly take it,’’ she said, with a nod at Marty. “Maybe he also borrowed from Jim Albert.’’

“Or, maybe the minister killed him so he could steal his money,’’ I said.

“Either way,’’ Maddie said, “a man as vain as Bob Dixon had to be humiliated that his dowdy old wife took up with someone else for a roll in the hay.’’

“A roll on a dirty plaid couch,’’ I said. “Delilah said it reeked of cigarettes.’’

“Whatever.’’ Maddie waved her hand. “The point is men do crazy things when women are involved. That leads me to the reason I don’t believe Jeb did it.’’

Marty’s eyes went round. “What do you mean?’’

“No matter what else I think about Jeb, I do believe he loved Mace.’’

“Loved her and regretted breaking her heart,’’ Marty said.

“So? What do Jeb’s old feelings for me have to do with anything?’’ I asked.

“The person who killed Jim Albert ran you off the road when you started asking too many questions,’’ Maddie said. “That wreck could have been a lot more serious, Mace. You could have been killed.’’

Marty gasped and grabbed at her throat, just the way Mama does.

“Yes, Maddie, but I wasn’t. I’m okay.’’ I reached over and patted my baby sister’s hand.

“Thank the Lord for that.’’ Maddie inclined her head to the poster Jesus. “Jeb Ennis wouldn’t do anything to hurt the woman he loved; maybe even still loves. He wouldn’t endanger you that way, Mace.’’

Maddie sounded so sure. I almost opened my mouth to tell her how I’d felt that afternoon in the park by Ollie’s pond: Stalked. Endangered. Not to mention confused, as I watched Jeb peel out with the windows rolled tight in a truck that was supposed to be stifling.

But in the end, I didn’t say a word to my sisters. I never told them how frightened I’d been that day.

The light from the headlamps on Pam’s VW bounced upward, illuminating hawk moths and the low-hanging branches of trees. At the end of the unpaved drive, Emma Jean’s house was dark. Deserted-looking. As I turned left to park the car, the headlights flashed across the front porch. The cat’s dishes and the rubber container of food were still there, just where I’d left them.

I killed the engine and turned off the lights. A waning moon barely broke through a thick layer of clouds in the sky. I heard night sounds: A dog barked a couple of streets away. Something small skittered through the dry leaves under the hedge lining the driveway. An owl hooted. The call sounded haunting. Lonely. I turned the car lights back on.

Talking with my sisters about all the people we knew who could have killed Jim Albert had left me feeling nervous.

“Here, Wila. Here kitty, kitty.’’

As I called, I lifted an animal carrier out of the car and set it on the rocky driveway. I grabbed a towel I’d put in the back seat. I’d been thinking about Emma Jean’s cat. I didn’t want to leave the pampered creature for too long on her own. I’d feel awful if Emma Jean did come home, only to find something had happened to her pet.

“C’mon, Wila. I’ve got food.’’

I tried not to sound too eager. I’m more accustomed to dogs than to cats. But a cat-crazy college roommate once told me that cats are just like men: Show too much interest and they turn tail and run; ignore them and they fall all over themselves for you. I arranged myself into a position of nonchalance on the bottom step of the porch. Plastering a bored expression on my face, I pretended to examine my fingernails.

“Okay, no big deal,’’ I announced to the night and to any Siamese that might be listening. “Come if you want. Stay away if you don’t. I’ll just sit here for a while and enjoy the music of the mosquitoes.’’

I started to hum.

Within moments, the cat padded out from behind a glider with a periwinkle-blue-and-white striped cushion. She seemed to remember me from before, but who can be sure? I stroked her a few times, murmuring nonsense words to her. I had the feeling Wila wasn’t going to like what was coming. But it was for her own good. Somebody had to take care of the poor critter.

I wrapped the towel around her, cocoon-like, except for her head. I lifted her into my arms, the towel protecting me from her claws. As quickly as I could, I stooped down, got her into the carrier, and shut the wire door.