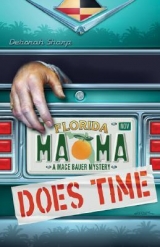

Текст книги "Mama Does Time"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Иронические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

I couldn’t help but remember how convincing Jeb had seemed back then. And all the while, he’d been lying like a tobacco company bigwig testifying to Congress.

“What in the name of Mike was all that about?’’ Mama slid her coffee cup back onto the counter and climbed up on the stool in front of the hamburgers Charlene had finally delivered.

“I don’t want to talk about it.’’ I stared straight ahead at the stainless steel wheel above the kitchen. So many white order slips were clipped up there, it looked like laundry day for a race of tiny people.

Mama reached over to straighten my bangs. “Well, I’m not surprised. You seem just about talked out after that scene with Jeb. What were you two whispering about, Mace? I could hear you all the way over to the table with Ruth’s grandson. The way you were hissing, it sounded like somebody stepped into a mess of snakes.’’

There was a snake, all right; and its name was Jeb Ennis.

“Mama, did you know Jim Albert loaned money to people?’’

“I didn’t know too much about him, Mace. But what I had heard, I didn’t like. Truth is, this whole marriage came up awfully fast. I don’t believe they dated for more than a few months. And I always thought Emma Jean could do better. I think she sensed I disapproved of Jim, because we didn’t talk much about him.’’

I took a bite from my burger and watched the order slips flutter in the breeze from an air conditioning vent. I was thinking about how Jeb was linked to Jim Albert, who in turn was linked to Emma Jean. And then there was Mama’s boyfriend, Sal, and his ties to everything. The whole mess was looking exactly like that nest of snakes Mama mentioned.

“Honey.’’ Mama tapped my shoulder. “Your purse is ringing.’’

I fumbled in my purse for my phone, past some packages of beef jerky and a jar of peanut butter, which I use to bait animal traps. By the time I found it, it’d quit ringing. I’ve got to get Maddie to sew me one of those little cell phone cases.

I went to the phone’s log and called back the last number that called me.

“Where are you two?’’ Maddie said. “Marty’s waiting for y’all. Mama left her things from the jail in the car this morning. Marty decided to run them by on her way home from her meeting at the library. You know that promotion she got? She’s running the whole show now.” My hamburger and fries awaited, salt crystals sparkling like diamonds on hot grease. I longed to take a bite, but I knew Maddie would yell at me for talking with my mouth full.

“How was church?’’ she asked.

“Just about like usual,’’ I lied. “We’ll tell you all about it tomorrow.’’

“I should have been there, too. But I couldn’t move a muscle after Kenny went and got us barbecue from the Pork Pit for supper. I ate so much, all I could do was unzip the waist of my slacks and lie there on my couch like a big, fat hog.’’

I got an image of my normally proper sister stretched out with her undies exposed, and smiled for the first time since Jeb sat down.

“Thanks, Maddie. I needed that. Listen, we’ll finish here and head over to Mama’s in about a half hour. Can you tell Marty? Tell her I want to hear all about the promotion.’’

“Will do,’’ Maddie said. “She already opened a bottle of Mama’s white zinfandel and she’s watching Cops on TV. It’s a good one, too, Mace. They caught this guy who got stuck in a hole he made in the ceiling when he was trying to burglarize a store. So far, I haven’t seen any of your old beaus.’’

Once, while watching the show, we’d spotted a boy I ran with during my wild period. Drunk and shirtless, he was being hauled out of a trailer on a drug charge. Maddie, of course, had never let me forget it.

After I rang off, Mama and I polished off our burgers, split the check, and headed home.

___

Teensy was running in circles and yapping at Mama’s front door. We could see Marty through the sheer curtain at the window, trying to navigate around the dog to let us in.

“Teensy, hush!’’ Mama shouted, which just pushed the Pomeranian over the top. He hurled himself at the door, intent upon breaking through the wood frame and hurricane-resistant glass to reunite with his mistress.

Marty finally got an ankle in between the dog’s chest and the door and pushed the little ball of fluff out of the way. She had one foot off the floor, a glass of wine in her hand, and the other arm wrapped around Mama in a welcoming hug. Marty was so graceful, she could pull that off. If I tried it, I’d be out flat on Mama’s hallway rug, covered in sweet wine and dog fur.

“Ooooooh, is this Mama’s little boy? Is this her itty-bitty boy?’’

Teensy launched himself straight up and levitated, like a Harrier fighter jet. She caught the dog in his skyward orbit, planting a big kiss on his head.

“Have you girls ever seen a more adorable little angel than this one?’’ She waved one of Teensy’s paws at us.

Marty and I exchanged a look. All that Teensy lacked was a bonnet and a bassinet.

We escaped to the kitchen, entering a veritable barnyard of gingham. Mama had a thing for cute animals in country checks: Her cookie jar was a pig in a gingham cap. Her canisters pictured ducks in gingham ribbons. Bunnies frolicked in gingham bowties along a wall border.

Marty hiked up her knee-length, linen skirt and climbed onto a step stool. She removed a wine goblet from the shelf, and poured me half a glass. I motioned her to keep going. We could still hear Mama murmuring sweet nothings to the dog in the living room. Teensy’s frantic barking had mellowed to an annoying whimper.

“God forbid anything should ever happen to that creature,’’ I said, lifting the pig’s gingham hat to help myself to two macaroons.

Her eyes widened. “Oh, Mace, don’t even think about it. She loves that dog beyond description.’’

“How was Cops?’’

“Funny, but sad. As usual. Where on earth do they find those people?’’

Unlike Maddie, Marty was too nice to mention my intimate knowledge of someone who’d had a starring role

“I saw Jeb Ennis again tonight.’’

Marty’s face lit up and she sat down at the table, ready for a good story.

“It didn’t go well.’’

I leaned against the counter and filled her in on what I’d learned about Jeb’s ties to Jim Albert. I told her how he’d tried to cover up their big fight.

“I need to find out how much he owed him, Marty. Money is an excellent motive for murder.’’

“You can’t suspect Jeb, Mace.’’ Marty shook her head, blonde hair shimmering in the wagon-wheel light hanging over Mama’s table. “You dated the man.’’

“Yeah, Jeb and that handcuffed suspect on TV. My taste in men seems a little iffy.’’

“What would his motive be for putting the body in Mama’s car, Mace?’’

“I’m not sure. I haven’t figured that out yet.’’ I topped off my wine glass, and grabbed a third macaroon. “But Jeb’s not the only one who seems suspicious, Marty.’’

I told her about Emma Jean’s scene at the church, and her threat of committing violence.

“Emma Jean said that bad word, right there at Abundant Hope?’’ Marty spoke around the hand she’d clapped over her mouth. “Maybe I was wrong about her being so nice.’’

We could hear Mama moving toward her bedroom, probably going in to change to something more comfortable than her pansy hat and pantyhose. Teensy followed, tags jingling on his collar.

“Marty, why didn’t you tell us about your promotion?’’

She blushed. “I didn’t want to make a big deal of it, Mace. Not with everyone so worried about Mama and the murder.’’

“Well, it is a big deal.’’ I clinked my glass against hers. “I’ve always known you had it in you. You’ve proved you don’t have to be bossy to be boss.’’

I’d made a small pile of macaroon crumbs on the counter. I was just about to get another wine glass from the cabinet for Mama when Teensy shot out of the bedroom like a rocket. The dog was going nuts, barking and scaling the couch by the window like it was the Pomeranian version of Everest.

Mama called out, “Mace, see what in the world is wrong with that dog. He hasn’t been the same since I went to prison.’’

“Jail, Mama.’’

A loud thump sounded from the wooden porch outside the front door. I grabbed Mama’s grandma’s heavy, carved cane from the hallway umbrella stand.

“Marty,’’ I whispered. “There’s someone out there.’’

Within seconds, my sister was right behind me, clutching a cast-iron pan.

Teensy was yelping and jumping, a Pomeranian pogo stick.

As I crept toward the window, I heard a car door slam in the distance. Outside, I saw nothing but dark, empty, street in front of Mama’s house. From down the block, an engine raced. Tires squealed. Whoever had been out there was now roaring away. Or, maybe that’s what they wanted us to think.

Mama, her face a white mask of Ponds cold cream against a red satin robe, joined us in the hallway. “What in heaven’s name is all the fuss, girls?’’

I shushed her, and motioned for her to grab hold of her crazy dog.

Cracking the front door, I peeked out. What looked like a bundle of rags tied to a heavy brick sat on the porch, next to a potted Boston fern. Mama held a wriggling Teensy. Marty sidled up beside me, frying pan shaking in her hand. We stepped onto the porch.

The rag bundle was the only thing out of the ordinary. I stooped to pick it up. It was a white toy dog. Deep slashes crisscrossed synthetic plush, spilling stuffing from the head and sides. A collar dangled from the nearly decapitated stuffed animal.

I held the collar to the light spilling out the front door. Marty and Mama each crowded in over a shoulder. Together, we read the name in crude letters on the mutilated dog tag.

Teensy.

I heard a sharp gasp and then another thump on the wooden porch, much louder this time. I whirled around to find Marty collapsed in an unconscious heap. The frying pan had missed my foot by about an inch and a-half.

“Oh, my stars! Would you look at my poor baby?”

I glanced at Mama, and was relieved to see she was referring to Marty, not Teensy. She’d put down the stupid dog and was focused on her youngest daughter.

“Mace, let’s get her up and onto the couch. You know Marty can’t take shock of any sort. Then run get a cold cloth for her forehead. We’ll lift her feet up on two pillows to get the blood flowing. Better bring that bottle of wine, too.’’

Mama’s tone had turned all-business. She might flirt and fuss and swan about like a Southern belle, but if the crisis involves one of her girls, there’s no one better than Mama to have in your corner.

Marty didn’t weigh much more than the sacks of puppy chow I lift to feed the abandoned wildlife babies at the park. If it’d been Maddie who fainted, we’d have been in real trouble. Mama and I easily carried Marty off the porch and into the house. We settled her on the living room couch, printed with salmon-colored roses.

“Get down off of there, Teensy!’’

The dog, ignoring Mama, was busy climbing across couch cushions and onto Marty’s chest. He’d moved up to her head where he was sniffing at her ear. He looked shocked when, none too gently, Mama swept him off her youngest human child and onto the floor.

By the time I returned with the items Mama had ordered, Marty was coming around.

“How’ya doin’, darling?’’ Mama murmured softly, stroking Marty’s baby-fine hair.

“Uhmmmm … uhmmm,’’ Marty answered.

“That’s all right, honey. You just rest right there. Mace and I have got things covered, don’t we Mace?’’

Not exactly, I thought, considering that someone had just tossed a brick and a decapitated stuffed dog at the house.

“What … what? That … the porch …’’

“Hush, Marty.’’ Mama put a finger to my sister’s perfect lips. “Everything’s going to be all right.’’

I moved a crystal candy dish full of butterscotch toffee so I could sit on the coffee table. Mama perched on the couch, next to Marty. I watched closely as her eyes focused. Then they clouded, worry taking the place of the confusion evident a moment before.

“That dog, Mace,’’ Marty said.

“It’s just a stuffed animal, a toy. It was someone’s idea of a joke.’’

“Teensy’s always getting into things, honey,’’ Mama said. “That little dickens probably chased a cat up a tree or tore up a neighbor’s flower bed. It’s just a message to keep my dog inside.’’

Even Mama didn’t look like she believed that.

I headed outside to the porch. Now that Marty was safely prone, I wanted to bring that stuffed dog inside for a better look.

I slipped my hand into one of the plastic grocery bags that Mama keeps by the door to remove Teensy’s messes from her lawn. Using the bag, I picked up the white dog. I wasn’t sure if the police could get fingerprints off a fluffy fake dog or a brick, but I was taking no chances.

Once I had the hallway light on and the stuffed dog displayed on Mama’s salmon-colored carpet, I noticed a slip of paper taped under the brick. I turned it over with the toe of my boot. The misspelled message was in the same crude letters as the dog’s name on the collar.

Stop questons on the murder or the real dog gets it. Then your next.

I raised my voice to carry to Mama and Marty in the living room. “I think we’d better call Detective Martinez.’’

___

Mama’s house smelled like a field of lavender flowers in Provence. Not that I’ve ever been to France, but it’s how I imagine it, anyway.

After she changed out of her robe, Mama had gotten busy with her candles and essential oils, intent upon easing our anxiety through the miracle of aromatherapy. She dabbed lavender oil on the warm bulbs in her lamps. She lit two candles for the coffee table. Dried lavender and ylang-ylang petals simmered in a pan of water on the stove.

We might have a stuffed-animal-tossing psycho stalking us, but at least we smelled good.

“How long before he’ll get here, Mace?’’

That was Marty, sitting up now, crumpling and smoothing the hem of her beige-and-brown floral blouse in nervous hands. Her leather loafers were tucked neatly under the couch.

“He said he’d be here as soon as he can,’’ I answered.

We sat quietly, listening to the hips on Mama’s Elvis clock swinging back and forth. Tick-tock. Jailhouse Rock.

Only fifteen minutes had passed since I phoned the police department to find Martinez. He called back quickly. But it seemed like the wait was going on hours. We stared at each other, trying not to let our eyes roam to the mutilated toy dog on the carpet.

Mama finally got up from the couch and rubbed her hands together. “Well, I don’t know about you girls, but all this activity has made me hungry. I think I’m gonna have me a bowl of vanilla ice cream with butterscotch topping. Anybody care to join me?’’

Marty turned green. But, nerves or not, I’ve never been one to turn down ice cream. Teensy and I followed Mama into the kitchen. She was spooning out the dessert when the dog did a double take, its little head twisting from the ice cream carton to the door and the outside beyond. Finally, Teensy’s territorial nature beat out his sweet tooth. He ran to the living room, barking like he believed he was a Doberman. I followed.

“Hush,’’ Mama yelled at the dog, to no discernible effect.

Headlights reflected through the windows out front, as a late-model white sedan swung into the driveway. Marty jumped up from the couch and flew into our old bedroom. I heard her lock the door from the inside.

Looking out the curtains, I yelled at my sister: “You can come out, Marty. It’s Detective Martinez.’’

The bedroom door opened slowly. I saw Marty’s pert nose and a curve of lip peek out. “Carlos Martinez?’’

“One and the same.’’

I watched from the window as he walked to the door, dressed in a white button-down shirt and gray slacks. Open collar. No tie. His hair was wet, like he’d just had a shower. I slammed shut the mental door on an image of him stepping out of the bathtub, water droplets clinging to his bare chest. The fact that he was frowning, as usual, helped end my inappropriate fantasy.

The doorbell rang, the dog started doing flips, and Mama came into the living room juggling three bowls of vanilla ice cream.

“Evenin’, Detective,’’ she said, as I opened the door for him. “You may as well have some ice cream before you have a look at the victim.’’ She held out the biggest serving, swimming in butterscotch.

Stepping inside, Martinez looked at the bowl like he suspected strychnine.

“Go ahead,’’ I said. “She’s already forgiven you for throwing her in jail. I can’t say the same for the rest of us.’’

Mama pushed the ice cream toward him.

“She’s not going to quit until you eat some,’’ I told him. I dipped my spoon into his bowl and took a bite. “See? Nothing but a frozen dairy treat.’’

He took it, mumbled a thank-you, and stood with his bowl over the stuffed dog.

“So it was just this toy and the note?’’ He carefully placed one of Mama’s Guideposts magazines on the hall table so he could set down the ice cream. I liked the fact that he was worried about leaving a ring on the polished wood.

He stooped down for a closer look. “Any idea who might’ve thrown it?”

All of a sudden, I felt cranky over everything he’d put us through by arresting Mama.

“Oh, gee, I don’t know,’’ I said. “Could it have been the real murderer? The one you didn’t catch while our mama was sitting in jail?’’

“Listen, Ms. Bauer.’’ His eyes darkened ominously. “I did what I felt was necessary with the situation and information I had at the time. I’m not going to apologize, or explain myself to you.’’

“Well, of course not. You’re arrogant. God forbid you should apologize.’’

“Mace, that’s enough. Please ignore my sister, Carlos.’’ Out from her bedroom fortress, Marty carried the quiet authority of someone who rarely spoke out. If she was moved to criticize, I knew I’d gone over the line.

“I’m sorry,” I said, chastened. “We appreciate you coming over here to check this out.’’

Martinez looked at me, raised eyebrows registering his surprise.

“We were all just so upset about Mama.’’ I tried to excuse my bad manners. “And now, this stuffed dog. We don’t know who tossed it. But I can tell you we have some suspicions about who might have killed Jim Albert.’’

He shifted, sitting cross-legged on the carpet to listen. I filled him in on Emma Jean’s threat in church. I told him about Jeb Ennis owing money to the murder victim. And I mentioned the mysterious Sal Provenza, again.

“That’s outrageous, Mace! Sally would never threaten Teensy. He loves him like his own.’’ Mama stroked the flesh-and-blood Pomeranian.

“In case you hadn’t noticed, the stabbed dog is a replica.’’ I crooked a thumb at Teensy.

The dog was splitting his attention between wary regard of the detective, an alpha-male threat in this female household, and pitiful begging for a bite of ice cream.

“I’d just die if anything bad happened.’’ Mama shoveled ice cream onto Teensy’s pink tongue. “Don’t worry,’’ she said, when she saw our disgusted looks. “He has his own spoon.’’

Martinez pulled a pair of gloves and a zip-top plastic bag from his pocket, slipped on the gloves, and picked up the stuffed dog. “I’m not sure how much we can get from this.’’ He dropped it with the note and brick into the bag.

“I hope I don’t need to tell you to keep your doors locked,’’ he said as he stood. “It may be a prank. But maybe it isn’t. And that’s a chance you don’t want to take.’’

Marty begged off, heading home with the beginnings of a migraine.

Mama managed to convince Martinez to sit for a spell at the kitchen table to finish his ice cream. I caught him checking out a family of porcelain mice in gingham bonnets cavorting across a display shelf. He dabbed with a gingham napkin at a tiny drop of ice cream on his white shirt. If that’d been my spill, vanilla on white cotton, it wouldn’t even merit action. When you go crawling around in the dirt after nuisance animals, you can’t be too fussy about stains.

“Mace, honey, why don’t you show Detective Martinez where the bathroom is, so he can get some soap and water on that spot?’’

Like a trained investigator would get lost traversing two rooms and a hallway to the toilet. Mama’s ploy was transparent. But I was too tired to point out he could find soap and water right there at the kitchen sink.

We pushed back our chairs, leaving Mama to place our bowls on the floor for Teensy to lap up the leftovers. Thank God her dishwasher water is good and hot.

Martinez stopped in the hallway on the way to the bathroom. Pictures of my sisters and me in various stages of development decorated the walls. I saw him grin as he looked at a circa-nineties shot of me in a starchy white dress, leaning against a tree. What had I been thinking with that ’do? I looked like Billy Ray Cyrus, with his mullet cut, in drag.

Martinez gently grasped my elbow, pulling me near. “Listen, I didn’t mean what I said before.’’ He lowered his voice so Mama wouldn’t overhear. “I do feel bad about putting your mother in jail. I wasn’t sure about the extent of her involvement. I’m new here. I’ve never had a whole family show up for what seemed like a party in the police lobby. And then no one would shut up. I could barely get in a word edgewise.’’

“We do tend to get a little rambunctious,’’ I allowed.

“It’s just that the police do things more formally in Miami.’’

I shook off his hand, crossed my arms, and leaned against the opposite wall. I wasn’t quite ready to forgive him. “Um-hum.’’

“You don’t give anything up, do you, Ms. Bauer?’’ His lips had formed into a half smile. “Maybe you should get a job as a detective.’’ He was standing so close, I could feel heat from his body. I caught the scent of cologne. Exotic, like sandalwood mixed with ginger. He smelled all male, and damn sexy. I took a step sideways along the wall.

“You’ve found out quite a bit in these last couple of days.’’ He stepped with me, staying close and keeping his voice low.

“It helps to know who to ask.’’ Mama always preaches modesty. She says there’s nothing worse than tooting your own horn.

“I’ll definitely follow up on your tip about that man with the cattle ranch. Jeb Ennis, right? And he lives in Woochola?’’

I had a guilty twinge about steering Martinez in Jeb’s direction. “Wauchula. We say, WAH-CHOO-LA.’’ I opened my mouth wide, like a speech therapist coaxing a stroke victim. “Mispronouncing these old Indian words will mark you as an outsider quicker than just about anything.’’

“I’ve had enough trouble with Himmarshee,’’ he said. “What’s it mean anyway?’’

“It’s supposed to mean new water, from an old Seminole legend about how Himmarshee Creek sprung up overnight. And don’t worry about your pronunciation. We’re probably all mangling the original Indian name anyhow. Just wait until you have to question somebody at Lake Istokpoga or Lake Weohyakapka.’’

“Thanks for the warning.’’ He bent in a little bow. “Gracias.’’

“No problem-o. You set me straight on the grammatical difference between prison and jail, remember?’’

He had the good grace to look embarrassed. “Pretty obnoxious, wasn’t I?’’

“You said it, not me.’’ I softened the criticism with a smile. Mama would be proud. “Anyway, the bathroom.’’

I gestured to the open door. The toilet, with its pink tulip seat cover, was perfectly visible through the frame. Even a bad detective could have discerned it. And from what I’d read in the Miami Herald, Carlos Martinez was a good detective.

I returned to the kitchen to find Mama feeding Teensy a doggie treat right at the table.

“Gross.’’

“Just ignore Mace, baby. You are not gross. You’re Mama’s little darlin’ dog, aren’t you?’’

I stood near the trash can, in case I needed to vomit.

Just about then, Teensy’s ears perked up and he leapt off Mama’s lap. The little nails on his paws scrabbled on peach-colored tile as he ran from the kitchen to the living room, barking all the way.

Before we had the chance to follow, we heard the front door jiggling. And then a loud knocking.

“What in the blue blazes? Open up!’’ More door-shaking, and a voice full of impatience. “Mama! Since when do you lock this front door?’’

Maddie’s irritation seeped right through the sheer curtain at the window.

By the time Mama and I made our way to the living room, Martinez had already opened the front door. “She locks it since I told her it was the safe thing to do.’’

Maddie’s mouth gaped open so wide, you could have docked an ocean liner inside. But all those years of dealing with whatever junior high-school kids can dream up had served her well. She recovered quickly.

“Detective Martinez.’’ With that inflection and the look in her eye, she might just as well have said “Detective Dog Poop.’’

“Happy to see you, too, ma’am.’’ Martinez matched Maddie’s insulting tone, syllable for syllable.

“Judging from the absence of handcuffs, may I assume you’re not here to arrest our mother again?’’ she asked.

Mama chimed in, “Now, before you say something you’ll regret, Maddie, we called the detective to come over. We’ve had a little spot of trouble.’’

“I know. I talked to Marty. She was in bed in migraine pain, with the lights out. I could barely hear her voice when I called. We only spoke a minute, but she told me about the dog.’’

“It could be simple vandalism,’’ Martinez said. “But we’re not taking any chances.’’

“Marty didn’t mention he was here.’’ Maddie pointed a long finger at the detective. She looked like the Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch, directing the evil monkeys at Dorothy and her pals.

But unlike the movie’s scarecrow, Martinez had a brain.

“I don’t want us to be enemies, ma’am.’’ His voice was warm and polite. “I hope your mother isn’t in any danger. But if she is, I really need your help.’’

Maddie was wearing flip-flops and her post-barbecue fat pants, but she still straightened to her school-principal posture. My sister loves nothing more than being needed.

“Well, of course, Detective. All of us want to do anything we can to help find out who really killed Jim Albert. For some reason, the murderer has involved Mama in this nasty business. Who knows what kind of message he’s sending with that stuffed dog?’’

“I’d like you to take a look at it.’’ Martinez was so respectful, he might have been seeking help from Scotland Yard. “Maybe something will strike you that didn’t strike the rest of us, ma’am.’’

“Lead the way, Detective. And please, call me Maddie.’’

“I’ll do that.’’ As Martinez turned to escort her to the stuffed dog, he threw me a wink. “And Maddie? Call me Carlos, por favor. Please.’’

___

Martinez left Mama’s a half-hour or so later. By that time, the compliments were flowing between my sister and him like floodwaters into Lake Okeechobee during the rainy season. I thought he was going to pin her with a special deputy’s badge at any minute. I actually saw Maddie bat her eyelashes. My sister being swayed like a schoolgirl was a sight to behold. Martinez must have studied with those Eastern mystics who are able to charm cobra snakes.

Maddie and I only stayed a little while after he left. We all were tired. And I had a long drive ahead to get home.

The streets of downtown Himmarshee were just about deserted. The yellow light blinked at Main and First. The sign at Gladys’ Restaurant was dark. A few cars were still parked at the Speckled Perch restaurant, where the bar’s open past midnight. Behind the wheel of Pam’s VW, I replayed in my mind some of the odd events of the evening: Delilah’s cutting remarks before church; my fight with Jeb; the mutilated toy dog.

As I sped past the courthouse on my way to State Road 98, I caught a glimpse of a familiar car from the corner of my eye. I slowed and peered toward the far end of the government lot, where the light is dim. Sal Provenza’s big Cadillac was parked next to a light-colored sedan. The two vehicles sat driver’s-side-to-driver’s-side, like squad cars sometimes do.

As I passed, Sal torched a fat cigar. I could clearly see his profile in the flickering glow. But who was in that other car, parked in a deserted spot for a clandestine meeting near midnight?

When Sal’s lighter flared a second time, I nearly ran Pam’s car into the war memorial on the courthouse square.

Carlos Martinez leaned from his driver’s window with an equally large cigar between his lips. Sal, smiling, fired him up. The detective puffed, and settled back in his seat with a contented look. As he exhaled, a smoke cloud swirled around the two men.

Sal relit his own stogie. Martinez said something. They both laughed. From my vantage point, now getting more distant in the rearview mirror of the VW, it looked like the investigator in Jim Albert’s murder and the man we all thought might be the killer were the oldest and best of friends.

I slammed on my brakes and did a U-turn.

The putt-putt-putt of the ancient VW made a stealth approach unlikely. By the time I navigated off the road, into the police department lot, and all the way to their corner in the back, Sal had started his car and gunned it. Pedal to the metal, he screeched out the exit like Dale Earnhardt Jr. in the last lap at Daytona.

As I sputtered up, Martinez got out of his car and leaned against the driver’s door. He looked completely relaxed; casual. Just an average, hard-working cop, enjoying a cigar at the end of a long day. Of course, his smoking pal happened to be the very same man Martinez had said was criminally linked to the dead mobster. And that wasn’t the least of it. He’d all but told me Sal was a suspect in that mobster’s murder.

I brought Pam’s car shuddering to a stop, and turned off the key in the ignition. Martinez walked over to the VW to greet me. “We meet again so soon, Ms. Bauer.’’

“Oh, can the act, Detective. It’s been a long day. I’m as tuckered out as a plow horse after forty rows. Why were you just sharing a smoke with the man you implied might have murdered Jimmy the Weasel?’’

“I like a woman who cuts to the chase.’’ He smiled down into the driver’s seat.

“I’m thrilled,’’ I said. “And I like a man who isn’t a pathological liar. What the hell is going on?’’

He looked right then left, like there might be someone lurking in the vast rows of vacant parking spaces. He turned around and peered behind us. Then he took a step around the front of my car and scanned the road I’d just come from. Unless someone was hovering over our heads or hiding underneath one of our cars, there wasn’t a soul to overhear him.