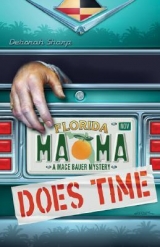

Текст книги "Mama Does Time"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Иронические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

I barely had time to process what Linda-Ann revealed about my one-time boyfriend.

I had to rush to work, where I was past late for an after-school event. Two third-grade classes were scheduled to visit the makeshift wildlife center I maintain at Himmarshee Park. A teacher from the last group of kids who came by sent me a letter, saying her students were still talking about the injured fox and scary snakes.

This latest group of kids was already there. I didn’t want to disappoint them by not showing up.

I could hear the din of thirty-one third graders as I crossed the little bridge over Himmarshee Creek and turned into the park. When I walked in the office and dropped my purse on the desk, Rhonda, my boss, shot me a relieved look.

“Thank God, you’re here, Mace. Those little monsters are tearing the place apart.’’

Within ten minutes, I had the students gathered in an outdoor amphitheater, ooohing and aaahing over the contents of a half-dozen cages. The star of the show, a bull alligator missing an eye and most of one foot, was waiting in the wings in his outdoor pool, ready to wow the kids for the show’s grand finale.

“Does anybody know what this is?’’ I held the first cage aloft. Two dozen hands shot into the air.

“A skunk!’’ cried a little boy in a red shirt who couldn’t wait to be called on.

“That’s right. But we don’t talk out of turn, do we? Anyone with the right answer today will get a special award. But you have to wait ’til you’re called on to get the prize,’’ I said.

“Now, this skunk I trapped because it was eating up the tomatoes in some lady’s garden. She definitely didn’t want it around because when she invited her friends over for cards, seeing a skunk freaked them out. It was probably somebody’s pet, because it had been descented. Who knows what that means?’’

Fewer hands went up this time. I called on the red-shirted boy so he wouldn’t feel bad.

“It means he don’t stink no more,’’ he said.

“Doesn’t stink anymore. Very good. Now, it was wrong to buy this skunk as a pet, and then let it go in the wild,’’ I said. “You know why? Because skunks use that stinky smell as a defense against bigger animals. Without it, this little guy was as helpless as a kitten.’’

And so it went for the next thirty-five minutes. A demonstration with something furred or slithery; a lesson about environmental responsibility. Finally, I herded the kids to the pool holding the seven-foot-long Ollie. There, I lectured them about staying away from alligators in the wild.

“Never, ever feed an alligator, or tease it in any way,’’ I said. “If they get too comfortable around people, it’s dangerous—not just for you, but for them. That’s when gators become what our state laws call a nuisance animal. And that means that someone with a trapper’s license—like my cousin, Dwight—can kill them and sell them for their meat and hide.’’

I thought of my stuffed-head key holder at home. It wasn’t that gator’s fault someone built a house with a pool in his territory. But once they did, it wasn’t safe for him to make himself at home there anymore. So now his head graced my coffee table, like a trophy buck on the basement wall of a deer hunter up north.

I pointed over a low concrete wall at Ollie, lolling in his pond. “Now, that gator’s here because he became a nuisance to people who like to play golf. But we didn’t kill him. We got special permission to keep him for educational purposes. Does anybody know what that means?’’

Hands shot up. I picked a little girl in a yellow sundress.

“Teaching?’’

“Right,’’ I told her. “Now, I’ll educate you a little about Ollie.’’

Thirty-one small bodies crowded toward the pond. “Careful, now! You may peek over, but you may not climb onto that wall.’’

When they’d chosen their spots, I continued, “A gator’s jaws are about the most powerful thing in the animal kingdom,’’ I told them. “If Ollie were to clamp down on your arm or leg, the pressure in his bite is more than sixteen times harder than your average big dog. His jaws are even stronger than a lion’s.’’

At this point, I tossed a whole raw chicken into Ollie’s gaping mouth. Some of the girls screamed when the gator’s jaws snapped shut over his meal. I took my bow.

Handing off the kids to one of their teachers, I collapsed on a park bench. I was staring up at the sky through the green-needled branches of a cypress tree when I heard a tentative voice.

“Excuse me, Ms. Bauer?’’

A pretty redhead peered at me from the end of the bench.

“I’m here with the kids,’’ she said. “They’re going to want to know: How’d Ollie get hurt?’’

“A fight with another male, probably over a mate. And if you think Ollie looks bad, you should have seen the other guy.’’

The line usually gets a laugh, but the teacher didn’t crack a smile.

“Uhm … I wonder if I could speak to you about another matter?’’

With the kind of day I’d had, with her hesitation and demeanor, this couldn’t be good.

“Sure.’’ I patted the bench next to me, inviting her to sit down. “What’s on your mind?’’

“I knew your mother real well. I mean, I know her.’’ She corrected the past tense. Mama wasn’t dead; she was just accused of killing someone else. “I was in her Sunday school class.’’

You and half of Himmarshee, I thought. But I was silent, preparing for the punch line.

“I wanted to tell you I’m sorry about her being in jail.’’ She sat, looking down to straighten the already perfect lines of her knee-length skirt. “I don’t think she belongs there.”

“We don’t either.’’

“No, I mean it’s impossible she did what the police say.’’

I sat up straight, fatigue forgotten.

She continued, “My mother plays bingo at the Seminole reservation, just like your mom. They were together at the casino yesterday, all afternoon. They had dinner there, and then played into the evening. At one point, before dinner, my mother got to feeling awfully cold. They keep the place air-conditioned like an ice house.’’

I drummed my fingers on the bench.

“Anyway, Ms. Deveraux told my mom she had a jacket in the trunk of her car. The two of them left the casino and walked way out into the parking lot to your mother’s turquoise convertible. Ms. Deveraux opened up the trunk. My mother said she moved aside some fishing tackle and a cooler before she found that jacket. And there sure was no body inside her trunk.’’

I felt like I was Samson, the Bible strongman, and the Lord had just lifted the heavy pillars of the temple off of my hands. I wanted to hug her, but settled for grinning like an idiot.

“That’s fantastic!’’ I jumped off the bench. “Your mother needs to tell that to the police.’’

The teacher stood up, too. “She already did. My mother called and told me a detective questioned her this afternoon. Spanish accent. Kind of rude, my mother said. He didn’t seem all that interested in her story about bingo, until she got to the part about Ms. Deveraux and her jacket.’’

I grabbed her by the arm. “What’d he say?’’

“Well, he wanted to know all about it. When, where, and how. My mother told him she saw clear into the back of Ms. Deveraux’s trunk. He argued with her, saying your mother might have collected the body from somewhere else before she wound up at the Dairy Queen.’’

I sat down again, thinking about why Martinez was trying so hard to indict Mama. Did he have something against bingo-playing grandmas?

“Did your mother tell the detective anything else that could be helpful?’’ I asked.

The teacher rolled her eyes toward her forehead, like she was replaying her conversation with her mother in her head. She touched the hem of her skirt. “She did tell him there was no way Ms. Deveraux could have snuck away. Your mother was on a hot streak all night. All the other ladies gathered round to congratulate her when bingo was over. She wound up going home with the two-hundred-dollar pot.’’

And that platinum-haired imp had never said one word about winning $200.

“Listen, would your mother be willing to go to the police department with me and tell her story over again? If we can’t get Detective Martinez to listen, we’ll just go over his head to Chief Johnson.’’

She didn’t hesitate a moment. “Absolutely. We’ll do anything we can do to help Ms. Deveraux.’’

Soon, the kids and the red-haired teacher were gone.

I fed the animals and closed up the park. It was late. I’d catch up my sisters by cell phone on my ride home. I couldn’t wait for a hot shower. All I wanted was that, and the fried chicken stuck in my fridge since last night, when Mama’s call had interrupted my supper.

My hand was on the doorknob to leave when the office phone started to ring. I wanted so bad to head on out and let the answering machine pick it up, but I was scared it could be someone trying to reach me at work with news about Mama.

I picked up the phone, and would come to wish I hadn’t.

“Mace? It’s your mother’s friend, Sal.’’

I looked with longing at the exit sign over the door in the park’s office. I’d been so close.

“What can I do for you, Mr. Provenza?’’ He’d asked us a hundred times to call him Sal, but my sisters and I addressed him more formally because we knew it irked him. At least Maddie and I did. Marty had barely said six words to the man in the year Mama had been dating him.

“It’s about Rosalee.’’

My heart skipped a beat. “Is she okay?’’

“She’s fine, so far as I know.’’

I let out my breath.

“But me and her aren’t,’’ Sal said. “I tried to see her today at the jail, and she refused my visit. That’s why you and me need to talk.’’ Tawk. “I don’t think she loves me anymore.’’

I felt like Robert De Niro’s shrink in the movie Analyze This.

“Then maybe you should have been truthful with her upfront,’’ I said. “Why didn’t you tell us last night at the police department you had ties to Jim Albert? Or, should I say, Jimmy the Weasel?’’

Pause. “How do you know about that?’’

“Detective Martinez told me. And I’m betting he told Mama, too. That’s probably the reason she won’t see you. She can’t abide a liar. Martinez is very interested in how you’re involved with a New York gangster, who then turns up dead in the roomy trunk of your girlfriend’s car. And, frankly Mr. Provenza, I’m interested in that question, too.’’

There was silence on his end of the phone. I could hear him taking raspy breaths. Sal really should give up smoking.

“I’m sorry, Mace,’’ he finally said. “I can’t go into all of that. Especially not on the phone. I’m out at the golf course, just finishing up eighteen holes. I played like crap. All I could think about is your mother.’’ Mudder. “Would you consider swinging by here on your way home?’’

The golf course, the centerpiece of a posh new development along a canal off Lake Okeechobee, wasn’t on my way home. I live north; the new course is south. But Sal seemed to be a key to Martinez’s case against Mama. I wanted to find out why.

“Please, Mace? There are some things I wanna tell ya, face ta face.’’ The harder Sal pleaded, the more his boyhood in the Bronx seeped into his speech.

I finally agreed to meet him at the golf course, which is out in the middle of nowhere, ten miles past the last trailer park in the Himmarshee city limits. He told me he’d wait at the snack bar, next to the pro shop.

When I got there, it was dark. Two floodlights illuminated the ornate pillars marking the entrance to the community. Himmarshee Haven, they said in cursive script. Luxurious Country Living. Talk about your oxymorons. Most of the country lives I know have very little luxury.

The Jeep bounced over a series of speed bumps as I made my way past Victorian-style homes with gingerbread trim and two-car garages. Most driveways featured golf carts parked behind white picket fences. Not a single double-wide trailer or swamp buggy in sight.

I parked in the golf course’s nearly deserted lot. There was no sign of Big Sal’s big car, but I decided to go inside anyway. I killed some time looking over the merchandise in the pro shop. Not that I play golf. But Marty does. I bought her a three-pack of those little ankle socks with the pom-pom that sticks out above the back of her golf shoes. The pom-poms were pink, mint green, and baby blue. Marty loves pastels.

As I handed over my credit card, I asked the college-aged kid at the register whether he’d seen a gargantuan golfer with a heavy New York accent.

“Sure, Big Sal.’’ The kid sucked on a breath mint. I could smell cinnamon clear across the counter. “He was in here about thirty, forty minutes ago. Then he got a call on his cell phone and high-tailed it outside. I heard the tires on his Cadillac squealing as he pulled out of the lot. Guess he was in a hurry to get somewhere.’’

He pushed my receipt toward me across the glass display case, which held dimpled golf balls and leather gloves. “Sign that, would you? And I’ll need to see some ID.’’

I gave him my driver’s license. He held it up and inspected it like he was a customs agent at the airport and I was smuggling heroin. “Hmmm, you’re thirty-one? I would have pegged you as younger. It’s not a very flattering picture.’’ He flipped a sun-bleached lock off his forehead and smiled at me, showing off even, white teeth. “You’re much prettier in person, especially your hair. I like the way it shines.’’

As he handed back my license, his fingers lingered against mine for a couple of beats too long. I couldn’t believe it. The kid was coming on to me. Must be the new ’do.

“Thanks.’’ I yanked away my fingers and slipped my ID back into my wallet. He put the socks in a little bag, and handed it to me as I headed for the door.

I was still smiling to myself as I climbed into my Jeep and started on the long drive home. Now, there was date potential, I thought: a pro-shop smoothie young enough to be my nephew. Maybe we’d drive to Orlando and I could take him on the teacup ride at Disney.

My “post-flirtus” buzz didn’t last long. Soon, I started wondering what the hell had happened to Sal. Why had he stood me up? That led to me worrying about how Mama was doing. It must be just about dinner time at the jail, which couldn’t be a good thing for someone who loves food. Before long, I was trying to fit together all the bits and pieces I’d discovered that day. I needed to prove to Martinez that Mama had nothing to do with Jim Albert’s murder.

I tried to picture me sharing some information that might replace his customary scowl with a smile. And then my brain took a quick, unexpected detour: how would those lips actually feel against mine I wondered. I traced a finger across my mouth and felt a warm twinge. Where the hell had that thought come from?

I quickly reined in my brain, and returned to worrying about Mama.

The road wasn’t crowded. I was deep in thought, puzzling out the pieces of her case. Occasionally, an unwanted image would intrude of Martinez’s face, of his strong hands; of his thick hair. Then, my mind would conjure Mama in her cell, and I’d feel guilty.

I didn’t notice the other car on my tail until I saw headlights flash in my rearview mirror. Maybe I’d let my speed taper off. I glanced at the speedometer. Nope, holding steady at sixty-six mph. That’s fast enough that no one should be riding my tail, lights flashing crazily. Peering into the mirror, I saw nothing but a white glow with a dark blob behind it. I couldn’t even say if the blob was car or truck.

Slowing, I waved my arm out the Jeep’s window. There wasn’t another oncoming car until next Tuesday. Go around, fool. He had plenty of room to pass, yet he stayed plastered to my bumper.

I eased over as far as I could to the right shoulder, giving a wide berth. It was probably a carload of teenagers, tanked up on testosterone and cheap beer. No way was I going to get into a pissing match with that mess. I slowed down some more, doing about forty now.

That’s when I felt a jolt from behind. I heard a hard, solid bump, high up on the back of my Jeep. It jerked me off the road, onto the rough shoulder. I wrestled with the steering wheel, fighting to keep control. The Jeep bucked like a rodeo bronc coming out the chute. My tires spit weeds and gravel. I tried to steer left, back to smooth pavement. But the other driver blocked my path.

Like freeze frames in my headlights, a mailbox, four garbage cans, and a barbed wire fence whizzed past. Then my lights swept across the white-gray expanse of a concrete culvert. It looked enormous, looming dead center in my sights.

And then I saw nothing but black

I saw that white light that everybody always talks about, gleaming in front of my eyes. A man’s voice called my name, softly, as if from a great distance.

“Are you there, Daddy?’’ I murmured. “Have you come to take me over to the other side?’’

I heard knocking.

“I’m not ready to go yet, Daddy. I haven’t been able to find out who really killed that man in Mama’s trunk. She’s still sitting in the Himmarshee Jail.’’

Rap. Rap. Rap. The knocking continued.

“Mace!’’ the voice repeated; louder and more insistent. “Are you okay?’’

Masculine features blurred, and then formed into a face, peering at me from above. Worried look. Firm jaw. Full mustache.

“Did you grow that mustache in heaven, Daddy?’’

“Mace! C’mon back to Earth, girl.’’

I could almost feel my synapses struggling to fire all the fog out of my brain. “Where am I, Donnie?’’ I finally asked.

Donnie Bailey, from the jail, stood in water to his waist. He was tapping his flashlight loud against the hood of my Jeep. Cracks branched out across the windshield’s glass like the bare limbs of a dead pine tree.

“You’re sitting in a ditch up to your wheel wells off Highway 98. Are you hurt?’’

I moved my left arm and then my right; lifted and lowered each foot. I was surprised to hear them splash into the water that swirled around the floorboards. When I put my palm to my forehead, I felt something else wet. I dropped my hand and stared at my own blood.

Donnie spoke calmly: “That’s a head wound, Mace. You might have banged it on the steering wheel, or caught some of that barbed wire through your open window.’’ He blinded me, shining his flashlight into my face. “That’ll bleed, but it doesn’t look too deep. Do you think you can undo your seat belt and help me get you out of that Jeep?’’

Barbed wire fencing was draped like Christmas garland across the Jeep’s front half. Donnie used the long handle on the butt-end of his flashlight to move the wire away. Pulling open my door, he leaned awkwardly into the driver’s seat.

“Put your arm around my neck, Mace. I’m gonna slip my hands under your legs and lift. Careful. You’re gonna be shaky.’’

He swung me clear of the door. “Very good,’’ he said. “Now, I’m going to carry you over and set you down on the hood of my squad car where I can get a look at you. Is that okay?’’ He was using that slow, deliberate, ABC-teaching tone.

“I understand you perfectly, Donnie. I’m not going into shock on you. Did I hit the concrete culvert?’’

I could smell the muddy sediment and the grassy scent of water spinach stirring as we moved. I hoped that was all that was stirring in that dark water. Donnie slipped a little climbing up the steep bank. I’m heavier than I look.

“You missed hitting it head-on. Grazed it.’’ He stopped at the top to catch his breath. “There’s a big scratch along the culvert. Then it looks like you flew over that grassy berm, and right into the water.’’

We waited on the bank, as Donnie gathered strength. Mosquitoes hummed in the still air.

“You can put me down. I’m fine.’’ I felt embarrassed that someone whose diapers I’d changed was carrying me like a baby.

“You’re not walking until I know what you’ve hurt.’’ He was still panting a little.

We made it the twenty feet or so to his car. He sat me down on the hood and grabbed a blanket from the trunk to wrap around me. Now, he was checking me over—noting whether my skin was clammy or warm; feeling my pulse. I’d done the same thing myself to injured visitors at Himmarshee Park. After toting me through the water and up a small hill, Donnie’s heart rate was probably worse off than mine.

“Can you feel that? Does that hurt?’’ he asked, pressing first on my midsection and then down my legs. “How ’bout that?’’ he said, moving on to the rest of my body.

My head felt as big as a balloon in the Macy’s parade, and my right knee ached like somebody smashed it with a mallet. “I’m fine, Donnie,’’ I lied. “Just shaken up.’’

“You’re lucky you didn’t wind up top side down in the water,’’ he said, moving aside my new hairdo to see if there were any more cuts. “I’d never have seen you if not for your headlights shining out over the canal. It’s a good thing we’ve had some dry days, or that water would have been higher.’’

He backed up a couple of steps, the better to view all of me at once.

“Looks like you’ll live.’’ He bent down to pick a long stem of hydrilla out of his shoe. I could hear the water dripping as he held up one foot.

“Thanks for coming to my rescue, Donnie. I might have stumbled out of the Jeep, fallen underwater, and never come to. I owe you.’’

“You should still have them look you over at the hospital, though. I’ve already radioed in about your accident.’’

Donnie using that word triggered my recall of the frightening moments before the crash. “It wasn’t an accident,’’ I said quickly. “Somebody deliberately ran me off the road.’’

I told him what happened, describing how the other vehicle had chased me, finally forcing me to lose control. “I’m telling you they bumped me, Donnie. Hard. If you check the Jeep’s rear end once it’s on dry land, you’ll probably find a scrape of paint or something from his car. I’m saying right now, this was on purpose. It was no accident.’’

I could see the skepticism in his eyes. “Why would someone want to do that, Mace?’’

“I’ve been out there all day, asking questions about Jim Albert. So far, all I’m sure of is Mama didn’t murder him. But maybe it’s making somebody nervous that I’m going to find out who did.’’

Donnie swung his flashlight out to the road and then to the ditch. Aside from the bugs he picked up in the beam, we were definitely alone now. “Or maybe it was just you out here. You were tired, and you fell asleep at the wheel. That’s nothing to be ashamed of, Mace. I’ve done it myself.’’

We both got quiet. I can’t speak for Donnie, but I was busy trying to think of a list of suspects who might have wanted me drowned at the bottom of a canal. Frogs croaked. Crickets chirped. I slapped at a mosquito that landed on my neck. In the distance, a siren wailed.

“Don’t tell me that’s an ambulance, Donnie. I don’t like ambulances.’’

“You need to go to the hospital to be evaluated,’’ he said stubbornly. “You could have internal bleeding or swelling in your brain.’’

“I told you: I’m fine. And I’m not riding in the back of an ambulance. They loaded my father into one after his heart attack, and that was the last time any of us saw him. I still remember the sight of those doors closing on Daddy. My sisters and I stood there in the road, watching until that ambulance was no bigger than a dot.’’ My voice trembled.

Donnie pulled at the collar on his shirt and looked down at the ground.

“Sorry,’’ I said. “A narrow escape from death might make anybody a little emotional. Now,’’ I said, shifting gears, “tell me why you can’t just give me a ride back to town?’’

“If it was any other night, I would. But my little boy’s sick, and my wife is already late for the night shift at the nursing home. My son needs me, and those old people need her. I’m sorry, Mace.’’

I felt bad for being so selfish. Not to mention ancient. I couldn’t believe my one-time babysitting charge was married with a boy of his own. That siren was getting closer. Even as banged up as I felt, I knew I’d rather walk to town than ride in that ambulance.

Suddenly, I had what seemed like a good idea. Then again, I might have had a brain injury.

“Could you call Detective Martinez?’’ I said. “I believe this might have something to do with the questions I’ve been asking about Jim Albert’s murder. Maybe he’ll think so, too. He’d want to get a look at things out here, in case it turns out this is a crime scene.’’

I could see Donnie thinking it over. The detective outranked him. He wouldn’t want to be blamed for making a mistake. I knew if Martinez came out, I could bum a ride back with him. I’d prefer even that to being shut into the back of an ambulance.

Donnie finally agreed, putting in a call for the detective. In the meantime, the ambulance crew arrived and checked me over. They did essentially what Donnie had done, except they used various medical gizmos to gauge my vital signs. They grumbled a little when I refused to be transported to the hospital. But I know my rights. I don’t have a cousin who’s a lawyer for nothing.

Martinez arrived just as the ambulance was leaving. Donnie met him by the road, and the two conferred, out of my hearing. Donnie was probably telling him how I’d hallucinated a chase scene after I got knocked on the head. That, along with my daddy’s visit from heaven. After Martinez stopped nodding, they headed my way.

He peered into my face. Not that I cared, but was that a flicker of concern in his eyes?

“How’re you feeling, Ms. Bauer?’’ he asked.

“Not crazy, if that’s what you want to know. Someone ran me off the road.’’

He put out his arm for me to grab hold of. I ignored it, and climbed down off Donnie’s hood. A shot of pain from my knee nearly took my breath away. My leg buckled, but Martinez caught me firmly by the waist. I was still shakier than I’d thought. But not so shaky I didn’t notice the hard muscle in his arm where he held me next to his side. Or the masculine way he smelled, like after-shave mixed with a faint trace of cigars.

“Steady, chica.’’ His warm breath in my ear sent a shiver south of my stomach. I wasn’t sure what the Spanish word meant, but it sounded nice. “Just take slow steps, okay?’’ Martinez said. “We’re going to get you to the front seat of my car. We’ll take our time.’’

He nodded curtly at Donnie, dismissing him from the responsibility of me. With a wave from the open driver’s side window of his car, Donnie bid me good-bye. “Remember what I said about dozing off, Mace. It’s nothing to have to hide.’’

I smiled and waved back. But I was simmering inside. I couldn’t believe Donnie thought I was making it all up.

“I’m telling the truth, you know,’’ I said, feeling cranky now.

As Martinez settled me into his passenger seat, I repeated what I’d told Donnie. Including how I thought my crash was linked to the murder. Every once in awhile, he’d nod, leaning against the inside of my open door, arms across his chest.

When I was done, he said, “I don’t disbelieve you, Ms. Bauer.’’

What the hell did that mean? He wasn’t calling me a liar, but he wasn’t saying he believed me, either.

“We’ll know more about how it happened when we can look over your car. The officer called …’’

“Donnie,” I said, annoyed. “He has a name.’’

“All right, Officer Donnie called for a tow truck. They’ll haul your Jeep to the Florida Highway Patrol, and tomorrow we’ll see what we can find. I’ve requested an accident investigator from the FHP. She’s coming out here to check the scene for skid marks, tire tracks, and anything else she can find.’’

He leaned across my body and fastened the seat belt at my hip. There was that cursed twinge again. Apparently, there was nothing wrong with my nether regions. His cologne smelled spicy, but subtle. It definitely beat the ditch water stench coming off of me.

After rummaging in his trunk, Martinez returned with three roadside flares. “I’m going to light these to mark the accident scene, and then you’re going to the hospital. Your friend, Officer Donnie, already gave dispatch the location, but these will help the investigator narrow it down.’’ He placed the flares on the car’s roof, and stooped to look at me. Brushing the hair from my forehead, he examined my wound. I was surprised at the gentleness of his touch. His hands looked so strong. I jerked away, but the warm impression from his fingers lingered.

“You were northbound when you went off the road, right?’’

“When I was run off the road,’’ I snapped at him, embarrassed by my body’s response to him.

“What were you doing out here anyway? It’s the middle of nowhere.’’

As if to emphasize our isolation, we heard the deep, bellowing grunt of a bull gator. All of a sudden, an image of Mama’s boyfriend flashed into my head. I couldn’t believe I’d forgotten to mention before now how he’d summoned me to the distant golf course.

“Salvatore Provenza, huh?’’ Martinez’s attention was riveted as I related my story. “And you say he wasn’t there when you showed up?’’

“That’s right. I didn’t even want to go out to that stupid golf course in the first place. I’d been busy all day, questioning people who might know something about Mama’s case.’’

“So I’ve heard. You’re quite the interrogator.’’ Did I see the tiniest smile cracking through the granite in Martinez’s jaw?

“Anyway, I was tired. All I wanted to do was go home, nuke some fried chicken, and vegetate in front of my TV. But he’s my mother’s boyfriend. And he sounded so desperate.’’

“Sal’s desperate all right.” Martinez rose. All trace of a smile was gone. “And you’d be wise to remember that desperate people do desperate things.’’

Dread settled like a boulder in my stomach as Martinez and I pulled up to Himmarshee Regional Hospital. I’m not afraid of doctors. But I am afraid of my older sister.

I could see Maddie through the plate glass window, washed in a red glow from the emergency room sign. She was sitting in a nearly empty row of chairs. The set of her mouth was as hard as the steel bolts that screwed the chairs to the floor. Marty was beside her, staring into space and worrying the tissue in her hands into shreds.

As soon as the doors to the waiting room swooshed open, my sisters jumped up as if they were stitched together.

“Thank God!’’ Marty ran to me and threw her arms around my neck. The tears started to flow.

“Come over here and let me take a look at you,’’ Maddie commanded, using her middle-school principal tone.

With my knee aching and Marty still clinging to my neck, I inched across the floor toward Maddie. I untangled myself, and Maddie clasped me by the shoulders. She turned me in a complete circle. When we came face-to-face again, I thought I saw a glimmer of moisture in her eyes. It was probably just a reflection from the hospital’s bright lights. She patted my arm, which turned into an awkward, one-handed hug.