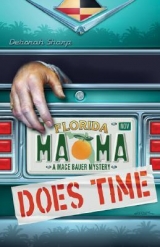

Текст книги "Mama Does Time"

Автор книги: Deborah Sharp

Жанры:

Иронические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

I moved on to wondering how I’d handle the obnoxious Martinez. I wished my sister Marty were here. People fall all over themselves to tell her things. As I weighed the best way to get information, an image of Martinez’s black eyes and sculpted features forced its way into my thoughts. I tried so hard to push it aside that my head started to hurt.

I turned my attention to a dusty stack of magazines. Leafing through Correctional News, I discovered there’s been a downturn in inmate suicides. I thought that was encouraging for Mama.

Then, I opened Police magazine, and read about the problem of sudden deaths in custody. I got depressed all over again. Browsing through the advertisements aimed at prison administrators failed to lift my spirits. There were no-shank shaving razors, so inmates can’t make knives. There was a restraint bed for the crazy or unruly prisoner, complete with floor anchors and slots for straps. The name of the bed, I swear to God, was the Sleep-Tite.

Glancing at my watch, I realized I’d already been waiting for forty minutes. I tried not to get angry. After all, my mother’s fate was in Martinez’s hands. I didn’t want to tick him off. I rehearsed how I’d approach him, concentrating on the flies with honey principle, like Mama advised.

Finally, Martinez walked into the empty lobby, frowning. He had a file folder in one hand and a cell phone to his ear.

Fifty-three minutes had crawled by since I’d given my name at the desk.

I started to rise from the chair. He caught my eye and motioned me to sit down. Then, he held up a warning finger. Don’t speak, it said.

I counted to ten real slow, gripping the arms of my uncomfortable chair. Pretending my hands were around Martinez’s throat, I squeezed until my knuckles turned white. Staring at the wall calendar, I pictured his smug face on the body of the large mouth bass. I imagined a hook grabbing hold of the soft flesh inside his cheek. I’d just formed an image of Martinez as half-man, half-fish, flopping airless in the bottom of a bass boat, when I realized he was speaking.

“I don’t know what you have to look so happy about,’’ he said.

He slipped his phone into the front pocket of his blue dress shirt. I cursed myself for noticing how snugly the shirt fit his broad chest, even as he stood glaring next to my chair.

“I was just thinking about fishing,’’ I said. “But you’re right. I have absolutely nothing to smile about. Not with my elderly mother imprisoned in a hell hole.’’

“Jailed, not imprisoned.’’

“I beg your pardon?’’

“Your mother’s in jail, not prison.’’ He tucked the folder next to his chest and crossed his arms over it, teacher style. “There’s a difference. Jails are locally run, and inmates are generally waiting to be tried. Or, they’ve been tried, and they’re serving a sentence of a year or less. Prisons are run by the state or the feds. Prisoners are usually convicted felons, serving sentences of more than a year.’’

“Thanks, Professor,’’ I said. “I’ll try to keep my references to correctional facilities correct whenever I explain to people how my mother is rotting behind bars.’’

“Actually, the rotting part comes after she’s convicted,’’ Martinez said. “Accessory to murder is a felony. It can buy you a long, long time in prison.’’

I could have throttled the arrogance right out of his voice. But then they’d send me to jail, and probably put me in that Sleep-Tite bed.

“It must strike you as strange that you’re the only one who believes my mother is involved in Jim Albert’s murder.’’ I forced a civil tone. “What evidence do you have that links her to the killing? Did you know my mother doesn’t even own a gun?’’

Ignoring my questions, Martinez looked down at a paper stapled to the file in his hand. “Is your mother acquainted with a man named Salvatore Provenza?’’ He rolled the R’s with Latin flair.

“You know she knows him,’’ I said, shifting my eyes away from the curve of his lips. “Sal was in here last night, raising a ruckus with the rest of us.’’

I didn’t reveal Big Sal was in line to become Husband Number Five. I wasn’t sure where Martinez was going with the question.

“So, he’s her boyfriend.’’ He made a little note on his paper. “Were you aware he had long-standing ties to the murder victim?’’

I knew it! My sisters and I weren’t just over-imaginative busybodies. Sal was involved in something criminal with Jimmy the Weasel.

“So?’’ I tried to sound casual. “That doesn’t prove anything. Sal and the man in Mama’s trunk were both from New York. Maybe they played on the same stickball team as kids.’’

Martinez looked at me like a teacher forced to flunk a once-promising student. “They played together, all right. But their game didn’t have anything to do with stickball.’’

“Well, what did it have to do with?’’

Another condescending look. “I’m not going to discuss that with you.’’

I thought of Henry, and the guessing games I hated. The more I wanted to know, the harder my cousin would withhold. I switched tactics.

“Whether you discuss it or not, I don’t see what any of this has to do with Mama.’’ I faked nonchalance. “Even if Sal is involved, why would you assume my mother is, too?’’

“I’m not going to share the nature of my information with you, Ms. Bauer.’’ He slipped the folder under his arm and touched the knot of his tie, as officious as a bureaucrat cutting off an unemployment check.

Had I really been thinking this smug jerk was attractive? It had been way too long between boyfriends.

“Let’s just say that when your dear mother isn’t teaching Sunday school, she’s consorting with some pretty rough characters,’’ he said. “The question is, ‘What did she know about the relationship between the victim and Salvatore Provenza, and what did she do about it?’ ’’

I remembered what Donnie Bailey had said at the jail. Hardly a woman behind bars doesn’t claim some man put her there. I got a mental picture of Mama sobbing in a cell, trying to convince a skeptical guard she’d been double-crossed by the man she loved.

If Martinez had his way, that sad scene wouldn’t play out in jail. It’d play out in prison—after he’d managed to convict my mama of murder.

The bells on the glass door jangled, announcing my entrance at Hair Today, Dyed Tomorrow.

Not that Betty Taylor, shop owner and news conduit, needed that cue. She probably knew the moment I made up my mind to visit, turning left from the police department instead of right.

Inside the beauty parlor, the harsh smell of permanent solution stung my nose. Hair conditioners, as fragrant as ripe fruit, softened the stronger odor. Flickering in the corner was a carnation-infused candle. That was Mama’s influence. In addition to her work with clients’ color charts, she’s also an aromatherapist. I’ll admit, the shop smelled girly, but oddly comforting, even to a tomboy like me.

Betty stood behind a chair, a pink foam roller in one hand and a strand of a customer’s wet hair in the other. Smiling at me in the mirror, she called out to her beautician trainee.

“D’Vora, c’mon out from the supply closet, girl. You won’t believe who’s here!’’

Betty did a quick twist of her customer’s hair with one hand, pulling another roller from her pocket with the other. All without breaking eye contact with my reflection in the mirror.

“Mace, toss the towels off of that chair and have a seat.’’ Another hair twist and roll. “What in the world is going on with our poor Rosalee?’’

I suppose it had been wishful thinking to imagine word hadn’t reached my mother’s co-workers. Gossip spreads at the shop like dark roots on a bottle blonde. It was just as well. I hadn’t relished the idea of breaking the news that Mama’s in the slammer.

D’Vora peeked out at me from behind the supply closet. “Mace, I’m so sorry about your mama. I just don’t know what to say.’’

D’Vora had managed to give her purple uniform some sex appeal. It was a size too small, and the top three buttons were undone. She’d appliquéd pink butterflies along the neckline, drawing even more attention to the suntanned valley between her breasts.

“That’s okay, D’Vora,’’ I said. “We’re getting the whole misunderstanding straightened out. That’s what I came by to tell y’all.’’

Her troubled frown faded. “See, Betty? Didn’t I say that? When I put that peroxide mixture on Rosalee’s hair, I didn’t understand how strong it was. And then the phone rang. I didn’t know leaving it on for just a tiny bit longer than the directions say would cause such a mess. It was just a misunderstanding, like Mace said.’’

Betty left her customer in the chair, click-clacked across the lilac-and-white floor, and snapped her fingers in front of D’Vora’s face. Snap. Snap. Snap. “Get with it, girl. That burned-up ’do you gave Rosalee is yesterday’s news. I told you she got tossed in the hoosegow. Try to focus, D’Vora.’’

D’Vora looked like a puppy spanked for peeing on the carpet. “I only wanted Mace to know I’m sorry about her mama’s hair. Of course, I’m sorry she murdered that man, too. Knowing Rosalee, she must have had a very good reason.’’

Betty shrugged an apology at me in the mirror. “You’ll have to excuse D’Vora, Mace.’’ She tapped the foam roller in her hand against the young woman’s forehead. “She was behind the door when God gave out brains.’’

I moved the towels and took a seat. “That’s all right. I just wanted to come and tell y’all that Mama’s a hundred-percent innocent. And we’re gonna prove it, too. She’ll be back here with her aromatherapy and seasonal color swatches before you know it.’’

“I’m sure of it, Mace,’’ Betty said reassuringly.

D’Vora didn’t look as convinced, but she kept her mouth shut this time.

“Honey, why don’t you sit right there and relax?’’ Betty asked me. “You look like a pair of pantyhose been put through the spin cycle.’’

And the day wasn’t but half over. I leaned back, shut my eyes and took some deep breaths. Usually, I don’t buy the aroma mumbo-jumbo, but the crisp scent was beginning to work its magic. Mama claims the scent of carnation oil reduces stress. I could use a little of that.

“Thanks, Betty. But just for a little while. I need to find someone else who could have committed the murder. I’m going to show this jerk of a detective from Miami that his case against Mama is a bunch of manure.’’

I try to watch my mouth around Betty, who worships with Mama at the Abundant Hope and Charity Chapel. She doesn’t cotton to cussing.

“We’ve heard all about that detective, Mace.’’ Betty spoke from around a purple comb she’d stuck between her lips. “My friend Nadine’s boy Robby manages the Dairy Queen. He told her that detective is as rude as can be. Nadine’s boy made the mistake of asking him how long they’d have the parking lot roped off while they looked at the body in Rosalee’s trunk. He didn’t mean nothing by it. It’s just wasn’t good for business. Who wants to come in for a banana split if a body’s drawing flies in the parking lot?’’

D’Vora interrupted, “I heard that detective’s easy on the eyes, but he’s downright mean. Nadine told Betty he just about snapped poor Robby’s head off at the Queen.’’

I knew the feeling. I think Martinez was still picking pieces of my own head out of his incisors.

“Absolutely snapped it off,’’ Betty agreed. “Just plain rude is what that is. But what do you expect? After all, he is from Miamuh.’’ She gave the word its old-Florida pronunciation. “You know how people are down there, girls. That place is worse than New York City.’’

I didn’t believe Betty had ever been north of Tallahassee, but that was neither here nor there.

“Speaking of New York, Betty, what do you know about the man in Mama’s trunk?’’

She quit rolling her customer’s hair and pulled the comb from her mouth, giving me her complete attention. D’Vora closed the supply closet and eased into a chair.

“We haven’t heard word one yet,’’ Betty said. “There’s only been a few clients in this morning, and so far nobody who’s known nothing. No offense, Wanda,’’ Betty nodded at the woman in her chair.

“None taken,’’ Wanda said agreeably.

Now all three women looked at me expectantly.

“It was Jim Albert,’’ I said. “Though I’ve since found out that wasn’t his real name.’’

Betty staggered theatrically, reaching out to steady herself on Wanda’s shoulder. “You don’t mean it, Mace,’’ she said. “I was just talking last week to Emma Jean Valentine about their wedding. She planned a burgundy and silver theme, and a three-tier cake with butter-cream icing. She wanted me to do her hair.’’

I sprang the rest of the story on them, about how he was really Jimmy “the Weasel,’’ and connected to New York mobsters.

As I spoke, Betty got animated, nodding and interjecting “You don’t say!’’ But D’Vora got real quiet. She returned to the supply closet, where she began shifting shampoo bottles.

“Don’t that beat all, D’Vora?’’ Betty called out, shaking her head.

“Sure does.’’ D’Vora’s tone was subdued, her head still stuck in the shampoos.

Now it was my turn to exchange a look with Betty in the mirror.

“Girl, what is up with you? C’mon out of there,’’ Betty said.

D’Vora closed the door slowly. She held a pair of scissors. A folded purple drape hung from her arm. “I’ve just been thinking about your poor mama, stuck in prison,’’ she said. “I think it’ll perk her spirits if we do something about your hair, Mace. She always says how you’re so pretty, but you won’t do a thing to improve what God gave you.’’

I was curious about D’Vora’s attitude shift when I mentioned Jim Albert. I could use a haircut; and maybe she’d talk. What the hell? I’d skip lunch.

Stepping behind my chair, she eyed my bed-flattened ’do. “What’d you cut it with, Mace? Gardening shears?’’ She lifted a thick hank of hair, letting it fall around my face. “See this jet black? It’s gorgeous, like something from the silent movies. With that and your baby blues, you could be a knockout. It’s a shame you go around looking like one of the critters you’ve dragged out from under somebody’s porch.’’

“D’Vora, I’ve told you about insulting the customers!’’ Betty warned.

“Mace isn’t a customer, Betty. She’s Rosalee’s kin. And I’m starting to believe she’s right about her Mama being innocent.’’

I jumped on that. “Do you know something to help me prove that, D’Vora?’’

Her frown came back. “I can’t say just yet, Mace. I want to get it right.’’

Betty caught my eye and made a slow-down motion.

“I’ll think on it while I work on your hair. No more questions ’til then,’’ D’Vora said.

I sat, and she leaned me back until my head rested on the basin. The shampoo smelled like green apples.

“What I meant about your mama …’’ She finally spoke again as she dried, rubbing so hard I feared scars on my scalp. “I’m just not sure what to say, Mace. I was taught not to speak ill of the dead. And part of it was told me in strict confidence by a customer. That’s like a patient and a doctor, isn’t it, Betty?’’

The two of them looked over at Wanda, who’d been moved to a dryer. She sat under a whir of hot air, devouring a National Enquirer.

“These are special circumstances.’’ I lowered my voice. “Mama needs your help.’’

She gave a little nod. “Well, first of all, you knew Jim Albert owned the Booze ‘n’ Breeze, right?’’

“Um-hmm,’’ I urged her along, even though I hadn’t known. I wanted her to get to the part about how someone else might have killed him.

“He had a secret business, too. Loaning money. He didn’t ask questions, and there was no paperwork, like at a bank. I’m embarrassed to say my husband, Leland, went to him once. He needed to borrow three hundred dollars. Leland was a week late paying it back.’’

D’Vora looked down, blotting at a shampoo splotch on her smock. “Jim Albert sent a man out to the house to break all the windows in our truck. He told us the next time it wouldn’t just be the truck. Leland came up with the cash, and we never saw him again.’’

She raised her eyes to me. “That Jim Albert was a man to be feared, Mace. What if someone else couldn’t pay what they owed? That would be a reason for murder, wouldn’t it?’’

“It sure would, D’Vora.’’ I felt like kissing her.

“And there’s more; about Emma Jean and the wedding.’’ Her eyes darted around the shop, as if she expected Emma Jean to jump out from behind a chair. “She came in a few days ago while Betty was out to lunch. She sat right in that chair and told me she was having second thoughts about going through with it.’’

I jumped at that. “Did she say why? What else did she say?’’

D’Vora turned her head toward Wanda. Still drying.

She leaned in close, cupping a hand around her mouth as she broke Emma Jean’s confidence. “She’d found out Jim was cheating,’’ D’Vora whispered. “She was so mad, she said she didn’t know whether she wanted to marry him or murder him.’’

Maddie was pacing outside her Volvo by the dumpster at the Booze ‘n’ Breeze when I arrived.

It was the first time in history my teetotaler sister and the drive-thru liquor store had been forced into such close proximity. When I called Maddie to tell her I found out some things that could help cut Mama loose from jail, she insisted upon meeting me at the Booze ‘n’ Breeze. It was her maiden trip to Jim Albert’s store, a den of sin in my sister’s mind.

The store’s about two miles east of the courthouse square in downtown Himmarshee. That’s far enough not to offend the good citizens who gather in the square for lunch, eating out of paper bags on benches under oaks strung with Spanish moss. But it’s also close enough so those same citizens can swing by for a nip on their way home from work.

In her black pantsuit, serious pumps, and reading glasses on a silver chain, Maddie looked every inch the school principal. Frown-ing, she glanced at her watch as she saw me drive up.

I parked on the weedy shoulder along Highway 98, and waited as a truck loaded with Brangus and Charolais cattle roared past. Then a battered pickup, its gate held shut with a length of rusty chain, clattered by. Six Latino farm workers in the back clamped their hands over their baseball caps, guarding them from the wind.

When I crossed the road and met Maddie by the dumpster, she stared at me so long I started to get nervous.

“What?’’ I asked her. “Do I still have sleep crud in my eyes? I know there’s nothing stuck in my teeth, because I haven’t had a bite to eat all day.’’

“What’d you do to your hair, Mace?’’

I put up a hand self-consciously, and felt nothing but smooth where there had been snarls that morning. Maddie grabbed my chin and turned my head this way and that.

“It looks good,’’ she finally said. “It really does.’’ She sounded shocked.

“D’Vora cut it,’’ I mumbled.

“My sister at a beauty parlor?’’ Maddie took a step back. “So that explains this awful foreboding I’ve had ever since Mama was arrested. The world really is coming to an end.’’

“Very funny, Maddie.’’ I snapped at her, but secretly I was pleased. A compliment from Maddie is rarer than a three-legged cat.

I told her all about Jim Albert, including his mob ties and the fact that Emma Jean had been furious after she’d found out he was running around with another woman.

“Jimmy the Weasel, huh? That cheating lowlife was an insult to the weasel,’’ Maddie said.

“Let’s go on in,’’ I told her, “and see what else we can learn about him.’’

There was no wall in front, since the whole idea of the Booze ‘n’ Breeze is to let shoppers motor past and get a good look at the libations. The business’s motto is, you never have to leave the driver’s seat to tank up.

The clerk looked at us in alarm as we stepped into the store from the drive-thru lane. She’d probably never seen a customer before from the waist down.

I smiled, harmless-like.

Maddie ratcheted up her customary frown. “Linda-Ann, tell me that’s not you underneath those stupid dreadlocks! And selling liquor, too?’’

So much for building rapport.

“I’m nine years out of middle school, Ms. Wilson,’’ the clerk said to my sister. “I’m old enough to work here, you know.’’

I could have told Linda-Ann not to sound so apologetic. The only defense against Maddie is a strong offense.

“I happen to like your hair, Linda-Ann.’’ I aimed a pointed look at my sister. “It’s a perfect style for you, especially with those cargo pants and that peace-sign T-shirt. So few young people these days show any individuality at all when it comes to fashion.’’

I was afraid I’d poured it on too thick, but Linda-Ann beamed beneath her blonde dreadlocks. “Thanks,’’ she said, smiling at me. “I like your hair, too.’’

“I thought you were going to college, Linda-Ann.’’ Maddie was judgmental.

“College isn’t for everyone.’’ I was understanding.

It was becoming clear who was the good cop and who was the bad in our interrogation tag team.

We waited while a car pulled in. The driver wanted a six-pack of Old Milwaukee and five Slim Jims. Dinner. It took Linda-Ann two tries to count out the change from his twenty.

Bad cop: “Didn’t you pay any attention at all in Mrs. Dutton’s math class?’’

Good cop: “You must be creative, Linda-Ann. Arty types are never good at arithmetic.’’

Maddie lost interest in creating rapport and asked Linda-Ann flat out what she knew about her late boss, Jim Albert. The clerk clammed up.

“Nothing really.’’ She twirled a dreadlock. “My manager told me the owner got killed, but I barely knew him. I’ve only worked here a few months.’’

Linda-Ann got busy rearranging a rack of pork rinds on the counter, even though they looked fine the way they were. Appetizing, actually. She straightened a hand-lettered sign that said Boiled P’nuts/Cappuccino, which I took as clear evidence that the yuppies were colonizing Himmarshee. She was doing everything she could in such close quarters to avoid us.

I knew we wouldn’t get anything from her—not with Maddie standing there radiating disapproval like musk during mating season. Linda-Ann was out to show my sister she wasn’t a little girl anymore, quaking on a hard bench outside the principal’s office at the middle school.

I dug into my purse, piling stuff onto the counter, until I found a pen and some paper. “Listen, our mother was tossed in jail because she can’t explain how come your boss’s body was found in her trunk.’’

Linda-Ann’s eyes widened.

“She didn’t kill him,’’ I said. “We’re trying to find out who did. We’d really appreciate anything you could tell us about Jim Albert that might help us do that, okay?’’ I jotted down my phone numbers and handed the paper over the counter.

“Let’s go, Maddie. Let’s let Linda-Ann get back to work.’’

Once we were out on the street again, I turned on my sister. “You have to learn to lighten up, Maddie. Not everybody responds to intimidation.’’

“Thanks for the tip, Mace. Seeing as how I’ve worked with young people all my life and you work mostly with raccoons, I appreciate the lesson in human psychology.’’

“Don’t get mad. I’m just saying sometimes you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.’’

“Now you sound like Mama.’’

I was beginning to realize there are worse things I could sound like.

Maddie and I put our argument on hold, stepping off the street as a pickup truck with mud on the flaps made its way from the drive-thru lane. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I caught a glimpse of the driver—black Stetson on his head, left arm in a cowboy shirt propped on the sill of his open window. My heart started pounding and my tongue went dry. I never imagined seeing him would send me for a loop; not after all these years.

“Jeb Ennis!’’ I yelled, before I even realized I’d opened my mouth.

“Oh, no,’’ Maddie said.

When Jeb spotted me, he lit up in a smile. Maddie’s face darkened. He parked his truck and waited to cross the road to where my sister and I stood. There was a steady stream of traffic—trucks carrying livestock feed and fertilizer, and the occasional tourist in a rental car who’d ventured far from the resorts on the coasts in search of the real Florida.

As Jeb waited for the road to clear, I had plenty of time to check him out: Blonde hair, blinding white smile, the tanned face of a man who works outdoors in the Florida sun. Tight, faded jeans fit his legs like blue denim paint. He was still long and lean; the years had added only a pound or two to his six-foot frame. First, I’d had inappropriate thoughts about Martinez. Now, seeing Jeb, my knees were as weak as a schoolgirl’s. I really need to get out more.

Reaching our side of the street, he spent a long moment staring at me.

“You look great, Mace.’’

And he looked good enough to eat. The attraction had outlasted anger, and the passage of a decade, at least. I shoved my shaking hands into the pockets of my jeans.

Jeb removed his cowboy hat and pushed a hand through his hair, flattened and slightly sweaty where the band had rested. “You’re sure a sight for sore eyes, Mace. How long has it been?’’

“Not long enough,’’ Maddie muttered.

“I think it was my first year of college,’’ I said, surprised when my voice came out sounding normal.

Maddie stepped in front of me, getting right in his face. “That’s when some horrible cowboy broke her heart. Tell me, Jeb, are you still riding rodeo?’’ She tossed him a smile like she’d rather it was a rattlesnake.

He nervously moved the hat in his hand to his waist, covering up the championship calf-roping buckle on his belt. “Nah, Maddie, I’m too old for rodeo.’’ He smiled back at her. “I bought myself a little ranch west of here, out near Wauchula.’’

“Not far enough,’’ Maddie said.

I bit my tongue before I echoed Mama and told Maddie to mind her manners. She was trying to watch out for me, and with good reason. On the other hand, a lot of time had passed. And the man did look mighty fine in his boots and jeans. He smelled of sweat and hay and the faintest trace of manure, which is like an aphrodisiac for a former ranch gal like me.

“I think my big sister was just leaving, Jeb.’’

I tried to signal Maddie by jerking my head toward the dumpster and her car, but she ignored me. “Maddie, don’t you need to get back to the middle school and torture some little children?’’

“I’ve got all the time in the world, Mace.’’ My sister shifted her purse from her right shoulder to her left, the better to take a swing at Jeb if she needed to.

“We were just talking about the owner of this place, that poor guy who got murdered. Did you know him?’’ I asked Jeb.

His eyes flickered to the drive-thru. “Only to nod at.’’

“You’re probably a pretty good customer,’’ Maddie said. “If I remember, drinking too much was among your many flaws.’’

“Maddie!” I said.

Jeb glared at my sister, his green eyes cold. “I don’t drink like I used to, not that it’s any of your business. I just bought a couple of cases of beer for the boys who work with me at the ranch.’’ He put his hat back on, straightened the brim, and dipped it a little toward Maddie before he turned to me. “We’re having a barbecue tonight, Mace. I’d sure love for you to come.’’

“Mace is allergic to barbecue sauce. Gives her hives,’’ Maddie lied.

I stole a quick look at his left hand. No wedding ring. Still, I wasn’t going to be that easy.

“I’ve got plans tonight.’’ I wish. “How about you ask me for the next one?’’

“Is your number listed?’’

“Mace doesn’t have a phone.’’ Maddie made a last-ditch effort.

“Ignore my sister. I’m in the book.’’

After he left, Maddie lit into me. “I can’t believe you’d give that devil the time of day, Mace. When he breaks your heart again, don’t say I didn’t warn you.’’

“I’m a big girl now, Maddie. And you didn’t have to be so rude. My heart’s been shattered a time or two since Jeb.’’

“But never as bad as that first time, Mace. Never that bad.’’ My sister glanced at her watch. “Now, I really am late. The kids will be raising a ruckus if I’m not there to supervise the school bus lines.’’

She got into her Volvo and rolled down the window. “I’ll talk to you after school, okay? We need to decide what to do next about Mama.’’

As Maddie pulled away, I started looking through my purse for my cell. I wanted to call my other sister, Marty, and tell her about running into the great love of my life. No phone. I remembered pulling everything out of my purse inside the Booze ‘n’ Breeze, hunting for a pen.

I walked back inside and saw Linda-Ann waving my missing phone over her head.

“I figured you’d be back for it,’’ she grinned.

“Listen, I want to apologize for my sister. She’s been a principal for so long, she treats everyone like they’re in the seventh grade.’’

“That’s OK. She’s just as mean as ever, though. You know how her name is Madison Wilson?’’

I nodded.

“Back in middle school, all the kids called her Mad Hen Wilson.’’

I leaned in close. “That’ll be our secret, Linda-Ann.’’ I didn’t tell her that Maddie was not only aware of the nickname, she embraced it.

“There’s something else I want to tell you.’’ She touched one of her dreadlocks to her lips. “How well do you know that good-looking cowboy who just left here?’’

“Pretty well. We used to date, a long time ago.’’

“Then you might want to ask him what he knows about the guy who owned this place.’’

I got an uneasy feeling in my gut. “Why’s that, Linda-Ann?’’

“That cowboy’s been in here a lot in the few months I’ve worked here. He always went back into the office to talk to Mr. Albert, and they’d always shut the door.’’

An old Ford rumbled into the drive-thru. I waited while Linda-Ann served a woman with three screaming kids, two of them still in diapers. I’d be buying booze too, if I had that brood.

As the Ford backfired and pulled away, the stench of burning oil filled the little store. Linda-Ann continued her story. “The last time the cowboy came in, they were back there yelling so loud I could hear their voices coming through the concrete wall.’’

“Could you tell what they were saying?’’

“I couldn’t make it out.’’ She folded a dreadlock in two and let it spring back. “But when the cowboy left, he slammed the office door so hard it about came off its hinges. Then he kicked over a whole display case of beer. Mr. Albert came out to the counter a couple of minutes later and told me to clean it up. I thought he’d be angry.’’

“He wasn’t?’’

“His face was ghost-white and he was shaking. He didn’t look mad. He looked scared to death.’’