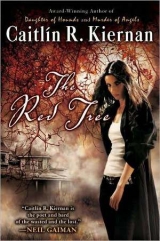

Текст книги "The Red Tree"

Автор книги: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

CHAPTER FOUR

July 6, 2008 (7:54 a.m.)

No coffee yet, and only one cigarette, and it only half smoked. If I were any less awake, sitting upright wouldn’t be an option. There was a very minor absence seizure last night, late; Constance had come downstairs to bum a cigarette, and she had not yet gone back upstairs when it happened. No big deal. I faded out for a few seconds, but she made a huge fuss over it. Can’t wait until she’s unlucky enough to be around for one of the big ones, if that’s how she’s going to react to the petit malepisodes. She brewed a pot of tea, and kept asking if she could look at my pupils, and if maybe I smelled oranges – stuff like that – and sat with me a while, though, of course, it was entirely unnecessary. I toldher it was unnecessary, but she insisted. It must have been almost four in the morning before she climbed back up into her garret and left me alone to try and sleep. And I really didn’t do much betterthan try. My head filled itself with all the sorts of unease that comes on nights like that, the unanswerable questions, the heavy thoughts to needle me and keep me awake. My health, the book, money, and also the story that Constance had told me about her ghost, the “ghost” she claims to have witnessed in Newport years ago. So, even though it’s probably not fair, I’m going to blame her for the nightmares that came when I finally diddoze off. It was almost five a.m., and the sky was going gray. I’m still not accustomed to how early the sun rises here, compared to Atlanta, and I really hate when it catches me off my guard like that. But I was sleeping before genuine daylight came along, thank fuck, or I wouldn’t have gotten even the lousy couple of hours that I managed.

The house is so goddamn quiet. Mist over Ramswool Pond. Birds singing. Little sounds I can’t identify. And these noisy fucking typewriter keys. Constance said not to worry about it, that, after her time in LA, she could sleep through an earthquake (and, in fact, she has, she tells me), but I still find myself trying to strike the keys with less force, endeavoring to somehow muffle that clack-clack-fuckity-clack of die-cast iron consonants and vowels against the paper and the machine’s carriage. The intractable guilt of the insomniac typist—sounds a bit like a stray line Ezra Pound might have wisely persuaded Eliot to cut from The Waste Land.

But the reason that I’m sitting here at the kitchen table (if I need a reason), painfully uncaffeinated, squinting at Dr. Harvey’s accursed typewriter by the wan light of eight ayem, are those nightmares I’ve already blamed Constance for summoning. Just another set of bad dreams, sure, in a parade that’s never going to end until I’m dead and buried (and, oh, what a happy thought, that death may come with nightmares all its own: unending, possibly, an afterlife of perpetual nightmares). But I can’t shake the feeling that there was something new there, and I want to try and put down some of what I recall before I lose it. It’s alreadyfading so goddamn fast, so quit stalling and get to it, woman!

I was walking by the sea, maybe one of the nearby stretches of Rhode Island coastline that I’ve visited – so, it’s no great stretch to understand why I’m blaming the tale of the “ghost” of the Forty Steps. I assume the tide was rising. It seemedto be rising, but I have spent far too little of my life by the sea to be sure. The surf was rough, the waves coming in and crashing against a beach that was more cobbles and pebbles than sand. The air was filled with spray. My feet kept getting wet. Well, I mean my shoes, as I wasn’t barefoot. My shoeskept getting wet, and my socks, because the foamy water was rushing so far up the beach towards the line of low dunes that stretched away behind me. The sky was the most amazing thing, though, and maybe if I weren’t so asleep I could find the language to do my memories of it justice. Maybe. Then again, maybe the demeanor of that sky is forever beyond my abilities to wordsmith. I know a storm was approaching, but no usual sort of storm. Something terrible, something magnificent rolling like a cumulus demon of wind and rain and lightning over the whitecaps, sweeping towards the land, and no power in the cosmos could have waylaid or detoured that storm.

At the library in Moosup, a while back, I read part of a book about the Great Hurricane of 1938, the fabled Long Island Express, and maybe that’swhat was in back of my sleeping conjuration of this advancing line of towering thunderheads. The colors, they’re still so clear in my head, a range of blue and blacks, violets and sickly greens bleeding into even sicklier yellows, and that does not even begin to convey those clouds. This was an angry, bludgeoned sky. A bruised sky. A sky bearing the contusions of some unseen atmospheric cataclysm.

I stood there, the polished stones slipping about beneath my wet feet as though they were imbued with a life all their own (and I wish I could recollect that line from Machen about the horror of blossoming pebbles, but I can’t, and won’t do it a disservice by trying). The wind and the spray swirled about me, plastering my clothes and hair flat, filling my nostrils and mouth with all the salty, living flavors and aromas of a wrathful sea. And as the gusts blown out before that storm howled in my ears, I realized that I was not alone, that Constance had followed me down to the shore. She was saying something about her former roommates, the Silver Lake junkies, but I couldn’t make out most of it. I told her to speak up, and, instead, she grew silent, and, for a time, I thought I was alone again.

The sea before me was filled with dark and indescribable shapes, all moving constantly about just below the waves, not far offshore at all, and occasionally something slick and black – like the ridged back of an enormous leviathan or the bow of an upturned boat – would break the surface for a scant few seconds. Smooth, scaleless flesh scabbed white-brown with barnacles and whale lice, or there would be a glimpse of writhing serpentine coils, or of tentacles, perhaps. there would be something festooned with poisonous spines as tall and broken as the masts of a sunken whaler cast up from the depths after a hundred and fifty years lying lost in the silt and slime.

And I felt myself leaning into the wind, and I felt the wind bearing my weight, the resistance of that stinging gale force pushing against my body. I could only wonder that it did not lift me like a kite or a dead leaf and toss me high, tumbling ass over tits, into the air.

Behind me, Constance remained taciturn, and as the storm’s voice grew ever greater in magnitude, ever more insistent, seeming intent upon devouring all othersound, her silence began to wear at my nerves. For whatever reason, her not speaking had become more corrosive than the salt and the lashing blow. As the storm chewed at the shoreline, so her refusal to speak ate at my nerves. And I turned to her, then, and she was standing naked, only a foot or so behind me, her clothing ripped away by the hurricane (if it wasa hurricane). Jesus, I need to get laid, because – despite the horrors of the dream – I woke horny from this vision of her, and writing it down, I’m getting horny again. Amanda always said I was easy. I never really argued with her on that point. But, anyway, there’s Constance standing buck-naked on this pebbly, shifting beach while the battered, choleric heavens assailed her pale and unprotected flesh. In that moment, I wanted only to throw her down on the sand and fuck her. I can admit that. Let the tempest take us both, but at least I could go with a goddamn smile on my face. In that moment, or those moments, I wanted to feel my lips against her lips, wanted the heat of her body pressed against my own, wanted to explore every seen and unseen inch of her with my hands and tongue and – yeah, it’s obvious enough to see where thatwas headed.

But then she did speak, after all, and her voice – though she spoke so, sosoftly – had no trouble whatsoever reaching my ears over the din of the storm.

“You went to Greece,” she said, “and what you remember most is a dead turtle?”

And in thatmoment, all my lust was transmuted to mere anger by the alchemy of human emotion. She was not Amanda, and I had never told her my Grecian sea turtle lie. This was a far greater intrusion than her arrival at the farm or her showing up uninvited in my dreams. This was some manner of mnemonic rape, I think, or so it seemed to me then.

“I never told you about the turtle,” I replied, struggling to stay calm, doing a lousy job of it.

“You went all the way to Greece,” she continued, staring past me, staring out to sea. “And then you wrote a book about it. But you left out that thing that made the greatest impression upon you?”

“There never was a fucking turtle,” I told her. “That was just a lie, because. ” and I trailed off, as the whysof my old lie were really none of her business. “I just made it up. And I’ve never told you about that night, about Amanda and the turtle and The Ark of Poseidon.”

She wiped saltwater from her flushed cheeks and smiled a sad, broken sort of smile. “Lady, you wear your past right out in the open, where anyone can see, if they only bother to look. So, don’t blame me for seeing what you’veput on exhibit.”

Behind me, the bludgeoned sky was suddenly lit by a flash of lightning so brilliant, so blinding, that it seemed to sear our shadows into the beach, like those photos you see taken after the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The sand will melt and turn to glass,I thought, waiting and bracing myself for that seven-thousand-degree fireball. But it didn’t come – no atomic pressure wave, no flames, no air superheated by X-rays to instantly vaporize the fragile shells of me and her. Only a thunderclap rattled the world, and then, as the rumble echoed across the land, Constance leaned forward and gently kissed me on the cheek.

“When I was a kid, Sarah, I always wanted a Lite-Brite,” she whispered in my ear, and not one single syllable was lost to the jealous, wailing storm, “but it never happened.”

“You are a thief,” I replied, not whispering. “You are a thief of memories that were never yours,” and she laughed at me. There was nothing cruel in the laugh, nothing spiteful. It was more the way you might laugh to lighten a tense mood, to put someone at ease, to make a moron feel less like a moron because she or he is so goddamn dense they can’t see whatever obvious truth is staring them in the face. And it only just this second occurred to me – presumably waking me – that it did notoccur to the dreaming me that Constance could have learned these things simply by reading the journal I’ve been keeping on Dr. Harvey’s typewriter. So, is this the subconscious expression of some unsuspected paranoia on my part? Is my sleeping mind fretting that I’ve never made any attempt to hide these pages where no one else can see them, or over my having written all this down in the first place?

“Two billion trees died in that storm,” she said. “Think about it a moment. Two billiontrees.” Before I could ask her which storm she was talking about, if maybe she meant the blizzard that brought her into this world like a lion, I saw that she was crying. Only, she wasn’t crying tears, but, rather, diluted streaks of oil or acrylic paints bled from the corners of her eyes, paint in all the shades of that awful storm, as though it had somehow gotten into her and now was leaking out again.

She wiped at her face, smearing the paint across her cheekbones and the bridge of her nose. Then Constance was not speaking, but singing to me, and while the music was a mystery, I knew the words at once—“ ‘What matters it how far we go?’ his scaly friend replied. ‘There is another shore, you know, upon the other side.’ ”

And because this is a dream, and because dreams appear even less fond of resolution than waking life, I woke. I woke horny and covered in sweat and gasping, nauseous and my chest aching, any number of panicked thoughts rushing through my mind – a heart attack? Another seizure? Maybe the seizure to come along and end all my fits once and for all. And too, I had not yet passed so completely beyond the borders of the dream that I did not still fear that hurricane bearing down upon me, bearing down to scrub away the shingle and me and Constance and two billion fucking trees. But, no need to worry, right? Because there is another shore, you know, upon the other side.

I’ve got to end this and get up off my fat ass and make some coffee. It’s almost nine, and I think I hear Constance thumping around upstairs. The typewriter probably woke her, regardless of what she’s been saying. Hopefully, we’ll get our postponed walk in today, out to “the red tree,” if the weather is not too hot and we’re not both too delirious from sleep deprivation.

July 6, 2008 (10:27 p.m.)

I’m admittedly at a loss how to write all this down – the events of the past twelve or thirteen hours – but I’m also determined that I willwrite it down. Some part of me is genuinely frightened, reluctant to put the experience into words, and, still, I find myself driven to compose some account of it. Are we back to writing as an act of exorcism? Wait, don’t answer that question. In fact, no more questions requiring answers, no more questions, just what I am left to believe occurred this afternoon when we tried to visit the tree. We talked about what happened over dinner, which Constance fixed because all I could do was sit here and smoke and stare out the kitchen window at twilight dimming the sky. We talked, but it was an indirect, guarded conversation punctuated with lengthy, uncomfortable silences. I asked her if she’d ever read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House,specifically the scene where Eleanor and Theodora get lost just outside the house and stumble upon a ghostly picnic. She hasn’t, and asked if I’ve read Borges’ “The Garden of Forking Paths.” I have. Of course, I have. We ended up talking about The Blair Witch Project,though that seemed to come uncomfortably near the bald factsof the matter, and so I brought up Joseph Payne Brennan’s short story “Cana van’s Back Yard,” precisely becauseI had a feeling Constance hadn’t read it. Inevitably, by fits and starts, we came to Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock,both the novel and Peter Weir’s film, to Miss McCraw and Mrs. Appleyard and her charges, Irma, Miranda, Edith, and Marion.

Constance said, “The girl who wasn’t allowed to go on the picnic, because she hadn’t memorized the assigned poem. The one who had a crush on Miranda? Wasn’t hername Sara?”

I didn’t answer the question, and, thankfully, she didn’t ask it again.

Yes, I know it’s sort of twisted that we had to resort to fictional metaphors and parallels because we were both too goddamned scared to talk about the thing straight on. But I suppose that’s what I’m trying to do now, talk about the thing straight on. Just write it down. Make it only words. Sticks and stones can break my bones, but. I’m starting to think maybe our dear departed Dr. Harvey figured out that words can do more harm than we generally give them credit. You’re stalling,Sarah.

Yes, I am.

We didn’t get out of the house until almost noon, and I’m not writing all that. Neither of us had slept very much, and we kept finding little chores that needed doing, little distractions. Hindsight can create all manner of illusions, and here, hindsight might suggest some prescience. You know, the man who misses his flight because he needs new shoelaces or Starbucks takes too long with his frap puccino or what the hell ever, and then he finds out the plane crashed, so surely some extrasensory force or guardian spirit was at work? That sort of thing. But the truthis we were bleary and distracted by exhaustion, and neither of us was really up to it. She didn’t get much more sleep than I did.

And she was still worried about me, because of last night’s seizure, and that kept coming up, and whether I was actually well enough for the walk. But the day was much, much cooler than yesterday, and the humidity quite decent, and I assured her that I would be fine. She pointed out that I couldn’t possibly know that, and I reluctantly conceded and told her that I’d learned I couldn’t let this condition turn me into a shut-in. I have no means of predicting these episodes, but I have to live my life, regardless. What I didn’tsay was, Constance, please mind your own goddamn business, although, by then, that’s what I was thinking. She’d asked me twice about my medication, had I taken it, should we carry it with us, what sort of side effects do I experience from it, do I tire easily, shit like that.

“We’re not even going a hundred yards from the back door,” I told her. And there’sthe single most damning fact of this thing, right there, the undeniable that I wish I could find some way to deny. We were not going even a hundred yards from the back door.

“Sarah, it’s just that I need to know what to do, if something happens,” she said, packing a canvas tote bag with bottled water and a couple of apples and the sandwiches she’d made. “And I don’t. I don’t know what’s myth, and what’s for real.”

“You saw what happened last night,” I replied. “What else is there you need to know?”

“Yeah, but that was only a little one, you said. Right? So what if there’s a really badseizure? What then? I don’t know what I’m supposed to do to help you. I mean, should I take along a spoon or something, to keep you from swallowing your tongue?”

I laughed at her, which didn’t help the situation, and said, “Only if you want to watch me break the few good teeth I have left.”

“It’s not fucking funny,” she growled and stuffed a whole handful of granola bars into her bag, enough granola to keep a troop of Boy Scouts hale and hearty and regular for a couple of days.

“No,” I said. “It’s not funny at all, which is probably why I make jokes about it.”

“Well, it’s not funny, and the jokes won’t help, if something happens.”

And so I told her what she could do, which really isn’t very much – that she should try to make sure I don’t hit my head on anything hard or sharp, and that she should roll me over into the recovery position, if possible, so I don’t strangle on saliva or anything. It seemed to help, just telling her that stuff, and at least she didn’t cram any more granola bars into the bag. I guess I’d taken the edge off the sense of helplessness she was left feeling after last night.

“How would I know if it’s bad enough to call an ambulance?” she asked.

“Constance, do I look like I could afford whatever it would cost to get an ambulance and paramedics all the way out here?”

“Jesus,” she sighed. “ I’dfucking pay for it, alright? I would pay for it before I’d let you lie there and die in the woods.”

I lit a cigarette and stared out the screen door towards that huge red oak, silhouetted against the cloudless northern sky. “If it ever lasts more than five minutes,” I said. “Now, are we going to do this, or stand here talking about my fits all day?”

“I’m ready when you are,” she replied. And that’s what was said before we left, as best I can now recall. There wasn’t much else said until fifteen or twenty minutes later, when we realized that we were lost. Or, rather, when we began to admit aloud to one another that we were lost. At first, I think it was more embarrassment than anything, embarrassment and confusion, and I’m sure we both thought that whatever had gone awry would right itself after only another minute or two. We’d simply gotten turned around somehow, that’s all. People don’t like to admit when they’re lost, not only from a fear of looking like a horse’s ass, but also because the admission entails an acceptance that one is in some degree of trouble. And, in this case, I spent half my childhood and teenage years in the woods back in Alabama and know well enough how to walk less than a hundred fucking straight yards from Point A to Point B, plus I’d already visited the tree once. Constance is a local and, despite her time misspent in Los Angeles, is also no stranger to walks in the woods. So, we were both fairly, and not unreasonably, reluctant to admit, even to ourselves, that something was wrong.

Near as I can tell, it started when we reached the break in the fieldstone wall and the deadfall of pine branches and had to leave the path to cross the stream running out of the pond in order to make our way around that impenetrable snarl of rotting wood, poison ivy, and greenbriers. We were both sweating by this time, and I paused at the stream to wet the bright yellow paisley bandanna I’d brought along before tying it once again about my throat. Constance crossed before me, and stood there staring in the direction of the red tree and Ramswool, talking about catching salamanders and turtles when she was a kid. I made some joke about tomboys, and then followed her across, noting how very dark the water was. I didn’t remember this from before – the somber, stained water – but it made sense, thinking about it. All that rotting vegetation surely produces a lot of tannin, which leaches directly into the stream. Where the water was moving, it was the translucent amber of weak tea, and where is wasn’t, here and there in deeper, stagnant pools, it was the rich, almost black brown of a strong cup of coffee. I associate this sort of “blackwater” with bayous and with the Southern coastal plain, and it seemed oddly out of place here on Squire Blanchard’s farm. Also, it brought to mind Dr. Harvey’s mention of the Bloody Run in Newport, that stream supposedly painted red with the blood of so many slain Hessian conscripts during the Revolutionary War.

She suggested we follow the west bank a little farther, as there was considerably less in the way of briars and underbrush on that side of the creek. And since we could still plainly see the upper boughs of the red tree from the broad gully the stream had carved, it made sense to me. The ground was a little muddy, and maybe the gnats and mosquitoes were worse, but the air was cooler down there in the leafy shadows of that hollow. We could always cross back over, scale the steep bank, and then the stone wall, when we were even with the tree. And now, typing this, another (rather obvious) literary parallel occurs to me, “Little Red Riding Hood” and the mother’s instructions that her daughter not dare stray from the path leading safely to her grandmother’s house. The Brothers Grimm, and Charles Perrault’s “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge,”and also, of course, Angela Carter’s retellings in The Bloody Chamber. Constance and I had strayed from the path, like mannish Miss McCraw and the four doomed students who followed her up Hanging Rock, or. digression, digression, fucking digression. Tell the story, Sarah, or don’ttell the story, but stop this infernal beating around the bush (and no, I shall not here initiate yet another digression regarding that unfortunate choice of words).

I think we’d walked for about ten minutes, when Constance noted how odd it was that the tree did not seem to be getting any closer. Or rather, that we didn’t appear to be getting any nearer to it. I laughed it off, said something about optical illusions or mirages, and we kept going, slogging more or less northwards towards the tree, which was still clearly visible. Fifteen or twenty minutes later, there was no longer any denying the fact that, somehow, the red tree had become a fixed point, there to the northeast of us, and that we should have already long since passed it and reached the edge of the pond. By then, it should have become necessary to turn 180° and look south to see the tree, but it remained more or less precisely where it had been, relative to our position, when we’d climbed down from the path to the nameless little stream.

“This is sort of fucked-up,” Constance said, not exactly whispering, but speaking very softly, as though she might be afraid someone would overhear.

“No,” I replied. “This is bullshit,” and I turned right, sloshing back across the tannin-stained water, getting wet to my knees and hardly caring. I scrambled up the bank, and over the fieldstone wall, and there was the path, and there was the far side of the deadfall, standing between me and the house, even though the pile of branches is, at most, only ten feet wide, and we would have passed it immediately,as soon as we began following the stream towards the tree. I stood there, out of breath, a stitch in my side, tasting my own sweat, and I shouted for Constance to get her ass up there.

After she’d seen it for herself, she shook her head and said, “It’s a different one, that’s all.” But the uncertainty in her eyes didn’t even begin to match the intended conviction of her words.

“Constance, I was here less than a weekago. Trust me. There was only one deadfall.”

“Well, then this one’s new,” she said, her voice taking on a frustrated, insistent edge. “ Theselimbs fell later, afteryou came through here, okay?”

I took the bandanna from around my neck and watched her while I wiped at my face with it. The stream water had long since evaporated, and the only moisture on the yellow cotton was my own perspiration.

“Fine,” I said, because I could see she was scared, and I know I was getting scared, and nothing was going to be accomplished by arguing about the hurdle of vines and rotting white pine blocking our route back to the house. “But how long have we been walking, Constance? How long have we been following that creek, with the tree not getting any closer?”

She looked at her wristwatch, and then looked towards the oak, and then looked back to me.

“I’m guessing at least half an hour, right?” I said, and, before she could reply, I continued, because I really did not need or want to hear the answer to my question. “And even if you take into account the time needed for us to climb down to the stream and back up here again, and the few minutes we spent by the water, talking about salamanders and tadpoles and shit, even if you take allthat into account, why aren’t we at the tree? How the hell does it take half an hour to walk three quarters the length of a football field?”

“We’ll clear it up later, I’m sure,” Constance said, turning away from the deadfall and towards the tree. But the wayshe said it, I was left with little doubt that she’d prefer I never even mentionthe matter again, much less try, at that safely unspecified, but later,point in time, to puzzle out what we’d just experienced.

She started walking along the narrow path, and because I had no idea what else to do, I followed her. All around us, the trees were alive with fussing birds and maybe a chattering squirrel or two. I still have a lot of trouble telling angry birds and angry squirrels apart. There was a warm breeze, and, overhead, the branches rustled and the leaves whispered among themselves. Constance walked fast, and so I had to move fast to keep pace. Before long, she was almost sprinting, her footfalls seeming oddly loud against the bare, packed earth of the trail.

Five or ten minutes later I was breathless and sweating like a pig, and I shouted for her to please stop before I had a goddamn coronary. And she didstop, but when she looked back at me, there was an angry, desperate cast in those brick-red eyes of hers. Those irises not unlike the tannin-colored water of the stream.

“ Lookat it,” I gasped, leaning forward, hands on knees, gasping for air and hoping to hell I could get through the next couple of minutes without being sick. “Jesus Christ, Constance, just stop and fucking lookat it.”

And she did. She stood there in the muttering woods, while I struggled to catch my breath, while my sweat dripped and spattered the dirt. She stared at the red tree, and then she asked, “Why doesn’t it want me to reach it? It let you, but it won’t even allow me to get near.” I am moderately sure these were her precise words, and I managed a strangled sort of laugh and spat on the ground.

“Let’s go back,” I said, doing my best to conceal my own confusion and fear. “Like you said, I’m sure it will all make sense later. But I don’t think either of us is in any shape to keep this up.”

“What if it’s me, Sarah?” she asked. “What if doesn’t want me getting close?”

I stood up, my back popping loudly, painfully, and I took her arm. “Let’s go back,” I said again. “It’s just a tree. It doesn’t want anything, Constance. We’re hot and confused and scared, that’s all.”

She nodded slowly, and didn’t argue. I held her arm and softly urged her back the way we’d come. She took a bottle of water from the canvas tote bag, twisted the cap off, and when she was finished, passed it to me. The water was warm and tasted like plastic, but it made me feel just a little better. I remembered the sandwiches and apples and all the damned granola bars she’d packed; if we werelost, at least we wouldn’t starve right away.

“Come on,” she said, returning the water bottle to the tote. “I don’t want to be out here anymore. I need to be home now.”

“That makes two of us. But, please, do me a favor, and let’s not try to make a footrace of it, alright?”

“Fine. You go first,” she replied, and the tone of her voice, her voice and the circumstances combined, there was no way I could not think of some adolescent dare. An abandoned house, maybe, a door left ajar, hanging loose on rusted hinges, opening onto musty shadows and half light. You go first. I dare you. No, I double-dog dare you.I was always a sucker for dares.

“If you keep your head, when everyone about you is busy losing theirs,” I said, and began walking south again, following the trail back to the house.

“Who said that?” she asked, and pulled her arm free.

“I’m paraphrasing,” I replied.

“So who are you paraphrasing?”

“Rudyard Kipling,” I told her, though, at the time I was only half sure it wasKipling and not Disraeli.

“The same guy that wrote The Jungle Book?” she asked, and I knew Constance was talking merely to hear her own voice, to keep metalking, that she was busy trying to occupy her mind with anything mundane. “Mowgli and Baloo and Bagheera, right?”