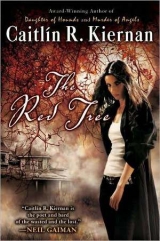

Текст книги "The Red Tree"

Автор книги: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

I have spread my dreams beneath your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Outside, the sky continues to brighten. The sky is the color of blueberry yogurt. Harvey’s unfinished manuscript is still in its box, here beside the typewriter. I’ve read the first two chapters. And that probably wasn’t so terribly bright of me, not after I figured out what his book is about, but curiosity and cats and all that. My dreams be damned, how would I notread it?

Look at this. Two and a half pages already, and I’ve managed not to get to the point. I have managed to skirtthe point, to dance around the peripheryof the point. Stop writing about dreams, Sarah, and writing aboutwriting about dreams, and just writethe dream.

The sky is going milky.

I cannot recall the beginning of it, but I was back in the basement with my flashlight. I know that I wasn’t looking for Harvey’s manuscript, because I clearly recall setting it down on one of the sagging shelves of pickles or machine parts or whatever, so I’d have a hand free. I was on the other side of the archway, past that odd threshold and its preposterous array of glyphs. I was somewhere past the threshold, trying to locate the north wall of the basement, pacing off my steps, one after the other, doing my best not to lose track and have to start over again. I realized that I must have walked very far beyond the house, and the footing beneath me grew increasingly wet. There were stagnant pools of black water standing here and there, pools whose depth it was impossible to judge, and I did my best not to step too near any of them. They seemed. unwholesome. Yes, that’s the word. Of course, truthfully, the whole damned place seemed unwholesome, as if I had somehow stumbled into an actual gangrenous abscess in the ground, a geological infection that had hollowed out this cavity below and within Blanchard’s land.

Here, where the pools of water began, there were far fewer shelves, and all of them contained nothing but antique books, volumes swollen from the moisture, their covers warped and spines splitting open like overripe berries. I did not stop to examine them, to learn any of their titles. I didn’t want to know, any more than I wanted to approach those motionless obsidian puddles. And this is when I realized that I was not alone. I heard footsteps first, and looking over my shoulder, I saw Amanda. Only, in death (and she wasdead, of that I am certain) she had taken on aspects of various of her photomontages, the sick fantasies of her pervert clients. She had the ridged and lyre-shaped horns of a male impala sprouting from her skull, and her eyes were as black as the pools of stagnant water. When she came closer, I could see that her cheeks and the backs of her hands were flushed with tiny scales that appeared to shimmer with some internal light all their own.

“Changed your mind, did you?” she asked, and when I nodded yes, she laughed – and it was so much herlaugh, in no way distorted by the dream. It was simply Amanda laughing, and I was grateful to hear it again. And then she asked, “So, was it inquisitiveness, or was it peer pressure? Or maybe you just got to thinking I wouldn’t want to fuck a woman who was afraid of the dark.”

“I am notafraid of the dark,” I replied, a little too emphatically. “It isn’t safe down here. They seal these places for a reason.”

“So, you’ve come to saveme?” and she laughed again, but the sound was neither as pure nor as welcome as before. “Are you my Lancelot? Are you the kindly huntsman come to rescue me from all the big bad wolves?”

And I told her no, it wasn’t anything like that, that I was only trying to find the north wall of the basement, because I knew it had to be there somewhere. I explained that if there were no north wall, then there’d be nothing to hold back Ramswool Pond. And since the basement clearly wasn’t flooded, it stood to reason the wall was there somewhere.

She shrugged and pointed at one of the puddles, not far from her muddy, bare feet. “You never can tell,” she said, “what goes on down below. Given any thought to where these fuckers might lead?”

“They’re mud holes,” I replied, growing impatient with the argumentative ghost of my argumentative lover. “They don’t lead anywhere.”

She smiled the sort of smile that maybe dead people commonly smile, and said, “You always were a woman of unfounded assumptions, Sarah.”

And around us, then, suddenly there were fireflies, and swirling motes of unidentifiable bioluminescence that seemed to make the darkness no less dark. The ceiling of the basement was draped with more than roots, I saw, with the sticky silken threads of larval glow worms, and I imagined there were zodiac constellations drawn in the arrangement of their deadly lures. Amanda held up her arms, as though she’d summoned this swarm, as though she worshipped or made herself an offering to it. And the basement had, I saw, grown into a cavern, something straight out of A Journey to the Center of the Earth,and forests of oyster-colored mushrooms the size of redwoods towered all around us. I heard the crashing waves of a not-so-distant sea, and Amanda sat down on a rock, and, slowly, she lowered her arms.

“So, what. You think this is usual?” she asked me, or some question very near to that, and I turned, trying to see the way back to the arch, and, past that, the foot of the stairs leading to a place that was only a basement.

“I don’t know what I think anymore,” I lied.“Perhaps you ought to put it back,” and I knew she meant the manuscript, Harvey’s manuscript, without having to ask.

“Perhaps you’re not ready for this.”

“That’s not for you to say,” I told her.

“And the typewriter, too,” she continued, as though I’d not even spoken. She did that a lot, when we were both alive. “It can’t be healthy, Sarah, having it around like this, workingwith it, a thing that has recently borne such strange fruit.” And if her allusion was lost on me in the dream, it’s not lost on me now.

The impala horns abruptly dropped from her head, and where they’d been nothing was left but two bloody stumps. She sat looking at them, the horns, and her expression was not so much sad as wistful, I think.

“Kind of makes you wonder,” she said, nodding at the shed horns. I waited for her to elaborate, but she never did. And I saw then that a variety of pale fungi had begun to sprout from her flesh, from her jeans and T-shirt, not so much devouring as simply augmenting,and I knew that, in this dream, I was neither a knight-errant nor a woods-man who saves lost girls from hungry wolves. nor from parasitic toadstools and yeasts, molds and agarics. I had already told her that, but as I watched Amanda’s body slowly, steadily bloom with the progeny of unseen spores, any doubt I might have harbored in this regard vanished.

There was more, what seems like hours and hours more, a roiling tumble of nonsense and phantasmagoria, a flight through that subterranean forest to the shores of Verne’s Mare Internum,his Liedenbrock Sea, perhaps. It may be I sailed a plesiosaur-infested ocean, or maybe I only sat on that alien shore, gazing up at a sunless, electric sky. But, however it proceeded, I don’t think I’m up to writing the rest. Whatever I might remember of the rest. The compulsion that drove me from my bed to this chair and the typewriter of Dr. Harvey has deserted me.

Since coming here, I have written two dreams, and damned little else, and in each one, of course, I encounter you, Amanda. In each one, I have no say in what becomes of you, so, in that respect, at least these are true dreams. Then again, in each one, you seem somehow imperiled, when I find it hard to believe there was ever any threat to you beyond your own penchant for self-destruction. So, paradoxically, the dreams may also be lies. Or both things are equally true – a particle and a wave, as it were – and I’m only being narrow-minded. A woman of unfounded assumptions, a woman of either-or.

But sitting here, watching the day coming on – a morning pregnant with the promises of yet another scorcher – it occurs to me that perhaps I should consider passing Harvey’s manuscript along to someone. I really don’t know who. Perhaps URI would want it, some former colleague or his department or the library or something, if his daughter in Maine truly has no interest. I surely do not need this new source of morbidity. I brought more than enough here withme. Maybe today I’ll try to call the university. I could drive it over, the manuscript, if there’s anyone there who wants it. If no one at the school is interested, maybe I’ll contact Brown or the Providence Athenaeum. At this point, I’d appreciate what I could deem a valid excuse to blow a tank of gas on the road trip and get away from this place for a day. And I can’t imagine that Blanchard would mind my getting rid of the manuscript. Not that I’ll bother to ask him, not after the way he’s foisted this new impending upstairs neighbor upon me. I googled her, by the by, and got nothing at all.

I suppose I could even try to track down the daughter; I doubt it would be very hard to do. I have her name from the obits. But there’s something, I think, inherently creepy and stalkerish about doing that. Unless Blanchard’s lying, she had a chance to claim her father’s work and passed. Who knows what that relationship was like? Maybe she’s glad the old man croaked himself, and maybe she even has a rightto be. Maybe he was a complete bastard, and the last thing she needs is some stranger butting in. It just seems somehow wrong that this manuscript has languished in the basement of a farmhouse for half a decade. Then again, this all supposes there’s something here worth saving. But I suspect I’m hardly qualified to make that call, and the same is likely true of Dr. Harvey’s disinterested daughter.

I need coffee. I need coffee, and I need to drive into Coventry for groceries. I’m down to my last can of Campbell’s Chicken and Stars soup and a little bit of peanut butter. And I’m awake now, and the sun is shining. I’m bleary as hell, and maybe the slightest bit drunk, but at least the damned dream has stopped feeling like anything more than another permutation of the Nightmare.

June 29, 2008 (10:27 p.m.)

The first bad seizure yesterday since leaving Atlanta. In Which Our Heroine is Lulled into a False Sense of Security. Yes, I’ve been drinking since I got here, a little, but I’ve been religious about my meds, and I think I had actually allowed myself to believe that shit was over and done with. Then, yesterday evening, after I got back from the market, after the trip to Coventry, I was washing dishes and. it occurs to me, now, I’ve never tried to describe one of these things. Vincent van Gogh, my favorite fellow epileptic, wrote in a letter to his brother, Theo:

“In my mental or nervous fever, or madness – I am not too sure how to put it or what to call it – my thoughts sailed over many seas. I even dreamed of the phantom Dutch ship and of Le Horla, and it seems that, while thinking what the woman rocking the cradle sang to rock the sailors to sleep, I, who on occasions cannot sing a note, came out with an old nursery tune, something I had tried to express in an arrangement of colours before I fell ill, because I don’t know the music of Berlioz.”

Hell, that makes it seem almost a desirable experience. Me, I have nothing so romantic nor pleasant to report. I was standing at the kitchen sink, setting the coffee cups out to dry on a dish towel, and then I was lying on the floor, staring up at the ceiling. Maybe ten minutes had passed. There was a small cut on my left hand from a broken cup, and I’d bitten my lip pretty badly, so my mouth tasted like blood. I lay there for a while, because sometimes they come in clusters. Sometimes it’s BAM – BAM – BAM. I lay there feeling sick and hungover and disoriented, dazed, stupid. I lay there, thinking about the firsttime, the first time to my knowledge, at least, and how badly it scared Amanda. I think it scared her a whole lot more than it scared me. She cried. It wasn’t the only time I saw her cry, but it wasone of the few times. She told me she thought that I was dying, and then there were all the goddamn specialists and tests I didn’t have health insurance to cover, and that’s what she shouldhave cried over. I spent most of the evening on the sofa, feeling Not Quite Right. I watched television and tried to read. I fell asleep and woke hours later with a crick in my neck, but feeling somewhat less strung-out.

Anyway, enough about that, the raging electrical storms behind my eyes. I thought maybe I had something to say here, something to match the grand dreamquest of Mon sieur Vincent van Gogh, but I don’t. I have a broken cup, a bandage on my hand, a swollen lip, a few bruises. missing time. I have the knowledge that this thingis still with me, this shaking malady, my tarantella, and I can sit here all night long wondering what part it played in Amanda’s death, and what part it is playing now in my inability to write anything more than these meandering entries on the typewriter of Dr. Harvey. For the first time since coming to this house, I wish there were someone else with me. Right now, for whatever reason, I don’t want to be alone. It’s not so much the fear, though I’d be lying if I said I’m not scared. I’m sick of my own company. I am weary of my own voice, of talking to myself, of talking and there being no one to answer me, but me. Then again, it’s really nothing I haven’t earned.

30 June 2008 (3:12 p.m.)

I spent the better part of the morning on the phone, mostly with people at URI, trying to find a final resting place for the manuscript. After being passed from one office to another to another and back again, from one secretary or administrative assistant or grad student or professor to another, round and round the goddamn mulberry bush, I finally found someone in the Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology interested in the manuscript. Only, she’s leaving for a vacation tomorrow and won’t be back in until after the Fourth, but I don’t suppose that matters a great deal. The box sat in the dank and the dark on that chifforobe for five years. Another week’s hardly going to make much difference. And it gives me time to finish reading the thing, even if Dr. Harvey couldn’t been bothered to finish writing it before stringing himself up. It’s grimly fascinating stuff, as promised by that first page I found, the bit about the “bloody apples.” Oh, sure, it’s grim stuff I no doubt shouldn’t bereading, out here with only the woods and the deer and my fits for company, but if I pretend it’s only fiction, how does it differ from any number of the novels in that stack I have not yet managed to read? I’m tempted to have it photocopied at the library in Moosup, just so I’ll have a record. I’m certainly not going to sit here and retype the whole damned thing. But I will transcribe the following passage, from Chapter One, because it gets straight to the heart of the matter, and I’ll confess it’s made me start thinking about looking for some other place to live (though the Coming of the Attic Artist already had me thinking along those lines). Harvey writes (on page 8 of the manuscript):

I will admit, since taking up residence here, I have considered on more than one occasion simply cutting the damned thing down myself. There is a chain saw at my disposal. I have thought of burning the tree, or salting the earth at its roots. But itisonly a tree, I remind myself, and these are only stories. There are days and nights when I have given my imagination freer rein than is healthy, evenings when I’ve spent too long trying to tease history from legend, truth from fancy. Is it only the power of suggestion, having read these letters, diaries, and newspaper accounts, that leave me lying awake at night, listening (though for what I cannot say)? Is it only having so submerged myself in the native lore surrounding the oak that repeatedly draws me down to sit on the wall nearest it and contemplate the seemingly purposeful interweave of those monstrous roots?

And, as long as I’m typing this, I may as well also include this,from ms. pages 3–5:

In this case, my personal introduction to the curious and often grisly lore surrounding the ‘Red Tree of Barbs Hill’ is the odd story of William Ames, second son of a wealthy English merchant. Following his father’s death, Ames emigrated from Weymouth to Boston in 1832, seeking his fortune in America. He soon found himself in Providence, having invested a considerable portion of his inheritance in one of the many new cotton mills springing up across New England in the wake of Samuel Slater’s refinements to the design of the water-powered spinning mill (1793). By all accounts, this enterprise was a great success, securing Ames a position among the city’s industrial elite. It is something of a mystery, then, why, in October 1836, William Ames sold his interest in the mill to his partners, having decided, instead, to try his hand at agriculture in the western part of the state. He purchased a large tract of land just south of Moosup, and built a house there on the foundation of an older house (indeed, the very same house in which I am composing this book).

There is little information regarding Ames’ life after his departure from Providence, though it seems that his farming endeavors met with far less success than his milling venture. He married a local woman, Susan Beth Vaughan of Foster, in 1838, but their marriage was to be a short and troubled one. Unable to bear her husband children, Susan Ames became a distant, melancholy, and sickly woman, and in August 1840, William woke one morning in an empty bed to discover that his wife had vanished from their home. An extensive search of the surrounding countryside was organized, but failed to turn up any evidence of her whereabouts or fate. There was a rumor that Susan had run away with a whisky salesman from Philadelphia, but Ames dismissed this story, insisting that he could hear his wife calling out to him at night. He reported that her plaintive cries were especially distinct near an old oak growing on the property, and a second, smaller search party was organized. Again, no trace of the woman was found, and despite her husband’s persistant claims, no one else was able to hear her nightly wailing but William Ames.

According to an account of his death, “Horror from Moosup Valley,” published in the Providence Journal, Ames also reported a “great wild beast, larger than any wolf or panther” roaming about his property, which left “scat and terrible marks from its talons” on his doors. The creature was seen more than once (but only by Ames) in the company of a woman he believed to be Susan Ames. Finally, less than a month after his wife’s disappearance, the farmer and former mill owner’s body was found beneath the same oak where he’d reported to his neighbors having so clearly heard Susan calling out to him for help. His corpse was mauled almost beyond recognition and had been partly eaten, and a subsequent hunt for his killer ended when a young timber wolf was shot just south of Ames’ property. Its belly was opened, but the Providence Journal article fails to record if human remains were found therein, stating only that the locals were “satisfied” they’d found the culprit responsible for the deaths of both Ames and his wife.”

Like I said, grim reading. And the more of it I read, the more my mind fills up with questions. For example, exactly how old isthis house, did this Ames fellow actually build it, and if it was constructed on a preexisting foundation, then how old is thatstructure? And is the basement (including the muddy area north of the archway where I found the manuscript) part of the original foundation, or was it dug later by William Ames in the 1830s? I suspect that these are questions that can be easily answered by the librarians at the Tyler Free Library, which is where I shall direct them next time I’m up that way, when I drop by to have Harvey’s ms. copied before handing it over to the folks at URI.

Looking back over what I said before typing out the two quotations, I can’t believe that I actually said this business about a “red tree” on Blanchard’s land has me considering whether or not I should be scouting for a new place to live. Pull yourself together, old woman. This is New England, and you can’t swing a dead cat without smacking a ghost or a haint or whatever. Worry about paying next month’s rent, not about pulling up stakes because the local folktales have you spooked.

July 2, 2008 (11:24 p.m.)

There was some sort of minor delay in the arrival of the Dreaded Attic Lodger, buying me an extra day or two of privacy before the invasion. But she’s coming tomorrow, or so I have been informed by the ever so thoughtful Mr. Blanchard. Thursday afternoon, he said. And Squire Blanchard wanted to know if, by any chance, I’d be around, just in case she had questions or needed help with this or that or what the hell ever.

I told him, “I feel it’s my solemn duty to inform you I’m not much of a Welcome Wagon. In fact, I might be the opposite.”

He laughed, even though I hadn’t, and then there was a long, uncomfortable pause in our conversation. I really do think he’s beginning to regret having rented this dump to me. Also, I was warned that he’d hired some Mexicans to clean out the attic (I can only assume that if the lodger hadarrived on time, she’d have been greeted by the dust and clutter I encountered up there the day I found the measuring stick). As promised, the cleaning crew showed up this afternoon, two men and one woman, and near as I can tell, they spoke not one word of English between the three of them. What I’ve retained from my two years of high-school Spanish barely allows me to order a taco and ask directions to the toilet. Quisiera un taco, por favor. Dónde está el tocador? Dónde está lavabo? Yeah. well, my language skills, my one purported talent, have never strayed particularly toward any foreign tongue (of course, there are plenty enough readers and reviewers who would argue I’m not so hot with English, either).

Anyway, the men hauled toolboxes, sheets of plywood, and some huge-ass shop-vac contraption up there, and before long the noise from all that hammering and shouting and vacuuming was intolerable. So I cleared out, deciding it was as good a time as any to visit Dr. Harvey’s apparently infamous tree. The manuscript places “the red oak” only seventy-five yards north of the house, just a few meters east of the low fieldstone wall that runs along much of the length of the creek flowing south out of Ramswool Pond. And, reading that, I realized the tree is within easy view of the goddamn kitchen window, that I’ve been staringat the thing for two months now with no idea whatsoever that it was anything more significant than the Very Big Tree between the house and the pond. So, not much of an adventure, except there’s a tiny wilderness of briars and poison ivy that begins just beyond the back stoop.

Do New Englander’s havestoops?

It was sunny, not more than a wisp of cloud in sight, and there was a nice breeze, so it seemed like a good day for a walk. And almost anything would have been preferable to the deafening roar of the shop vac and the pounding hammers. I pulled on the leather boots I rarely wear, a long-sleeve T-shirt (despite the heat), a pair of jeans, and grabbed a bottle of water from the fridge. I spritzed myself with tick repellant and smeared some sunscreen on my face. Then I lingered a moment in the kitchen doorway, looking out across and through the undergrowth towards that huge tree, its upper boughs silhouetted against the blue sky, wondering how many times during the past two months I’ve seen it, how many times I’d sat staring directly at it, and I considered how Dr. Harvey’s text had changed a tree into an object of. what word would be appropriate? There’s a quote from Joseph Campbell that I’ve always loved, and it seems to apply here: “Draw a circle around a stone and thereafter the stone will become an incarnation of mystery.” Or something to that effect. Clearly, to my mind, a circle had been drawn about that old tree, and no matter how many times I’d already seen it, no matter how ordinary a tree it might in fact be, the story of doomed William and Susan Ames and everything else I’d read in those pages had traced a circle about the oak (and I’m sure Campbell would have agreed that if it’s true for a stone, it’s true for a tree).

I had only a little more trouble reaching it than I’d expected. The poison ivy is fucking rampant, and though I’ve never been allergic to it, not to my knowledge, there’s always a first time. Also, about halfway to the tree, the wall’s collapsed, and the “path” is blocked by a deadfall of jagged pine branches that I wasn’t about to try to go over or through. Instead, I crossed the shallow creek, skirting the jackstraw tangle of branches and tumbled stones. My feet got muddy, and then climbing back over the stone wall where it resumed north of the deadfall got me to speculating on what sorts of poisonous snakes lurk in those woods (turns out, thank you, internet, there’s some confusion over whether or not there are any venomous snakes in Rhode Island; there might be copperheads and timber rattlers, but, then again, there might not). I spotted a couple of rabbits, a doe, and almost twisted my ankle two or three times. By the time I reached the tree, it was nearly four p.m., and I was mosquito bitten and drenched in sweat. There’s a large slab of rock at the base of the tree, and I sat down on it to get my breath and wipe away some of the sweat stinging my eyes. It’s harder to see the house from the tree than it is to see the tree from the house, and I assume this is the result of some vagary of topography and vegetation.

At any rate, all in all, the tree was a disappointment. Not much of a mystery, no matter how many circles Harvey and the local yokels might have drawn around it. It’s big, sure. Huge, really. But. that was that. A huge oak tree. I was underwhelmed – though, honestly, what had I expected? To hear the ghostly, disembodied voice of lost and presumably wolf-gnawed Susan Ames calling out to me across a hundred and sixty-eight years? I was too tired to even think of heading back right off, so I lay down on the wide slab of granite or whichever brand of igneous rock is exposed at the base of the tree, and just lay there a while, staring up into the branches. There were catbirds, and they fluttered about and scolded me for intruding upon whatever secret catbird affairs they conduct out there. Truthfully, despite the sweat and the scratches from greenbriers, despite the bug bites, it was nice being there beneath the tree. So what if it has a bit of a bad reputation. So do I. In fact, I suspect I could have fallen asleep there, if not for all the noise the catbirds were making. Certainly, Harvey’s talk of cutting the tree down or burning it – his evident fearof it – seemed entirely absurd, lying there, sheltered from the sun by its broad, whispering leaves.

When I’d gotten my second wind, I sat up and examined the oak a little closer. The roots are genuinely impressive, enormous, like gnarled, arthritic fingers digging into the soil and ferns and detritus of the forest floor. It was impossible not to be reminded of Tolkien’s ents, and, in particular, of Old Man Willow snaring Merry and Pippin in the crushing folds of its trunk, but even these thoughts, of that cunning, black-hearted tree in Bombadil’s Old Forest, failed to elicit from me any actual dread of “the red oak.” A little awe, maybe, that this great tree still stood after all these long decades, after centuries, seemingly impervious to the ravages of time. I walked about its periphery, and found a few places where people had carved initials and dates into the wood. I’ll have to go back and write them down. The only one I recall offhand is “1888,” which I assume was carved into the bark more than forty years after the whole Ames affair had supposedly occurred.

It’s getting late. I should take my pills and go to bed. I have no idea what time that woman will actually show up tomorrow. I ought to get up early and head for Providence or Newport, stay gone a few days and let her wonder, let Blanchard worry about whatever questions she might have. But what I oughtto do and what I doare very rarely ever one and the same.