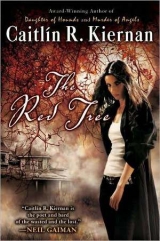

Текст книги "The Red Tree"

Автор книги: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“I think Amanda might have told you she was both.”

“Do you have any of her work here?” Constance asked, and I shook my head. I don’t. Everything of Amanda’s that I still own (including her artwork) is back in Atlanta, in the storage unit there. I almost brought a scrapbook with me, printouts of fifty or sixty of her favorite pieces. She referred to them as “giclées”—what she sold to her clients and from her website.

“There’s still some stuff online, I think,” I said. “Unless her agent or someone else has had it taken down.”

“That seems unlikely,” Constance said very softly.

“Does it?”

She didn’t reply, but sat, uninvited, on the floor a few feet away from me. She offered me a cigarette, and, having one offered, that’s not the same as bumming. She also offered me a light, but I had a book of matches in the pocket of my robe. I smoked and stared at the rain streaking the south-facing window.

“I’m scared,” I said, and the paranoid woman curled up inside my skin cringed, and cursed, and called me a traitor.

“We’re bothscared,” Constance said. “I’m not ashamed to admit that. I only work the way that I’ve been working when I’m hiding from something, Sarah.”

“So, you’ve been hiding from something since you arrived,” I said, and laughed. Thinking back, I wish that I hadn’t, but it slipped out, like the smoke slipping across my lips and out of my nostrils. And it pleased the paranoid woman. Maybe she’s the one who laughed, and it wasn’t me, at all.

“Haven’t we both been hiding?” Constance countered. “You think the only baggage I brought back from LA was the crap you helped me carry in? Fucking shitstorm out there,” she said. “I’ve been trying to forget about it, just live my life and forget things bestforgotten.”

“I never said that Amanda was something best forgotten,” the paranoid woman muttered, all but whispering, and kept her eyes on the window. Constance sighed loudly, and apologized. It made me want to hit her; I’d not asked for an apology, and I didn’t expect one.

“That’s really not what I meant,” she said. “It just came out wrong. I know there’s not a one-to-one correspondence going on here, Sarah. We both got bad shit in our immediate pasts, that’s all I mean. And then we come here, and what do we get? Chuck Harvey’s pet fucking obsession. That goddamn tree. . ” And I’ll say she trailed off here, because I got the distinct impression that there was something else she wantedto say, but didn’t.

And now the paranoid woman was yammering from someplace inside my head, intimations of seduction and guile, insincerity and head games. I silently told her to shut the hell up and leave me alone, but, I admit, I also hung on every word she said. Constance wanted something. Probably, Constance had wanted something all along, and I was getting tired of waiting to find out what it might be.

“I know that I shouldn’t be shutting myself away up there,” she said and pointed a finger towards the bedroom ceiling and the attic. “But it wasn’t so bad. . I mean, maybe I didn’t quite realize what I was doing, until youshut yourself up in here.”

“Not room enough in one house for two reclusive mad-women?” I asked, and she didn’t laugh.

“Is that what you think, Sarah? That we’re insane?”

“Don’t you? I mean, isn’t it preferable to the alternative?” And I stopped staring at the window, then, and stared at her, instead. “Oh, wait. You’re the one who opened a wormhole to 1901 and reached through space and time to stop that woman from shooting herself. I nearly forgot that part. So, for you, I guess thisisn’t so strange at all, is it?”

Constance stared back at me for a second or two, then let her eyes stray to the floorboards. She laid both her paint-stained hands palms down on the varnished wood and took a very deep breath. The paranoid woman smiled with my mouth, no doubt quite entirely pleased with herself.

“We can be cunts about this,” Constance said, and it sounded as though she were choosing her words now with great deliberation. “If it’s what you want, we can each retreat to our respective corners of the cage, and cower there in our own private misery and fear. We can be alone while we wait to see what happens next, if that’s how you think it ought to be. But it’s not what I want, and you need to know that.”

“What do you want?” I asked, crushing my cigarette out on the floor. “What do you expectme to do? I’ve already told you I don’t have the money to leave this place, to find somewhere else to live. So, will it really be so much better if we cower in the same corner? Is that what you want, Constance, someone to hold your hand while we wait for whatever came for Charles Harvey, and all those other people, to come for us? Or is it just the sex? Is the fear starting to make you horny?”

Constance shook her head very slowly and licked anxiously at her lips, which I noticed were very raw, chapped, like she’d been gnawing at them.

“You won’t even try to listen,” she said. “I can leave here, Sarah. If I’m willing to leave you alone with that. .” and she glanced towards the north wall, but I understood that she was really glancing towards the red tree. “All I have to do is pack my shit and make a phone call or two, and I couldbe somewhere else.”

“Then that’s what you should do,” I told her, and used an index finger to wipe at the ashy gray-black smear I’d left on the floor. “In fact, that would probably be for the best, don’t you think?” And I said those things. I know perfectly well I said those things, or something similar. There seemed no possibility of reaching all the way down to the solid bottom of my anger, the bedrock bottom of the well of spite and bitterness and resignation that’s opened up in me after my last visit to the oak. It just goes on and on, that great invisible wound, like the cavern below this house goes on and on. It didn’t matter one iota that what I wantedwas to put my arms around Constance, to beg her not to leave, to tell her how much it terrified me even to thinkof being alone. The paranoid woman spoke from the wound the tree has left in me, and I simply could not summon the will to silence her and deny her and permit the day to take some other, less self-destructive, route.

“Yes, you should go,” I said.

“Sarah, I’ve told you already that I’d never leave you here. I couldn’t do that. I won’t.” I glanced at Constance from the corners of my eyes, and she looked like she was about to start crying. Seeing that pleased the paranoid woman no end, and the wound in me grew wider by some terrible, immeasurable increment.

“Don’t you darestart crying,” I sneered. I could say “the paranoid woman” sneered, but I’m not letting myself off the hook so easily. Isneered, and I balled one hand tightly into a fist. “It makes me sick to my fucking stomach, the sound of a woman crying.”

“Is this how you talked to Amanda?” Constance asked, covering the lower half of her face and turning away from me. “When she needed you, is this the way you treated her?”

“We’re not talking about Amanda,” I said, and clenched my hand so tightly that my short nails dug bloody half-moon grooves into the flesh of my hand.

“No,” Constance replied. “No, I don’t guess we are.”

“It’s onlya tree,” I said through gritted teeth, full in the knowledge that I’d never told so great a lie in all my life, and would never find one to top it. “And if you think differently, I believe there’s an ax in the basement. Or Blanchard would probably loan you a chain saw, if you think you’re up to it.”

Constance wiped at her nose, and quickly stood up. It wasn’t hard to see that I’d frightened her, or, to be more precise, that I’d added another dimension to her fear. At the time, it seemed like I’d only evened the score.

“I’ll be in the attic,” she said, and left me in the bedroom, easing the door shut behind her. When the lock clicked, I went back to staring at the window, at the rainy day outside, and tried not to think about the tree. Later, though, I took the piece of human jawbone I found in my jeans pocket yesterday and tossed it out the back door, into the high grass and weeds.

I’m going to stop typing now. I don’t think I can bring myself to say anything more.

August 4, 2008 (9:17 a.m.)

“The images produced in dreams are much more picturesque and vivid than the concepts and experiences of their waking counterparts. One of the reasons for this is that, in a dream, such concepts can express their unconscious meaning. In our conscious thoughts, we restrain ourselves within the limits of rational statements – statements that are much less colorful because we have stripped them of most of their psychic associations.

”Carl G. Jung, Man and His Symbols(1964)

August 4, 2008 (10:01 a.m.)

The house is so awfully quiet this morning. Maybe Constance took my advice and left in the night. I would almost believe this, the house is so quiet. There is no sound of her footsteps from upstairs. I am dressed, but have spent most of the last hour sitting on my bed, watching the south-facing window, and the trees, and the sky. Occasionally, I have heard a bird or an insect, but these noises seem to be reaching me from someplace far, far away, and are muffled by distance. I am unaccustomed to there being such a profound silence in this house. You can always hear the birds, the cicadas, the wind, the creaking of venerable timbers still settling after hundreds of years, whatever. This is a new sort of quiet.

So, yes, I wouldthink that Constance Hopkins has gone, and I am alone; that she left in the night, only I hardly slept. My body seems to have found some way around the meds. The Ambien has ceased to work. I don’t know. But I wasawake, save maybe half an hour between three and four, and then an hour (at most) between about seven-thirty and eight-thirty. Both these intervals are plainly far too brief to have accommodated her departure. I feel certain of this. She couldn’t have gotten out of here that quickly. Constance wouldn’t have dared to go on foot, not after her talk of coyotes or wild dogs on the property, and a car or truck would surely have awakened me.

Am I alone? It should be a simple enough question to resolve. Leave my room, and learn whether or not I am alone in the house. I did leave once already, but only long enough to go to the bathroom. I didn’t try to find Constance, because, honestly, the possibility that she’s gone had not yet occurred to me. The profundity of this silence had not yet occurred to me. I figured she was sleeping, and then I realized that I couldn’t hear her window unit chugging away up there. That’s not so unusual, early in the day, but it started me thinking, I suppose. It would serve me right, after what I said to her yesterday. I am well enough aware of that. It’s nothing I wouldn’t have coming.

I’ll go looking for her when I finish this entry. I’ll go upstairs and knock on the door to her garret, and she’ll tell me to get lost, or we’ll make nice, or she’ll ignore me, but there will be some minute sound to betray her presence. I’ll press my lips to the keyhole and whisper apologies, and assure her that I wasn’t myself yesterday. I wasn’t. But I think that I’m getting better now.

There was a dream this morning, and I want to write it down, all of it that I can recall. I know it was the honesty that comes in sleep, that it was me trying to get through to me. I started to write it earlier, but didn’t get any farther than that quote from Jung. I suppose I intended it as some sort of an abstract or preface, a deep breath before diving headlong into icy waters. Then, as I was typing the last few words of the excerpt, there was a sudden rustling in the bushes below my window (the west window), and I had to stop and try to see what it was. But I couldn’t seeanything out there, nothing that could have caused the commotion, and I’m going to assume it was only a rabbit, or a bird, or an errant breeze.

I have never been comfortable writing out my dreams. That used to mystify Amanda. Or she claimed that it did. I know that I’ve included only a handful of dreams since I began keeping this journal, back in May. I had a therapist, years ago, who insisted that I keep a dream journal as part of our work together. I reluctantly acquiesced, but made at least half of it up. She never knew the difference, and reading back over it, later, I discovered that I had a great deal of trouble distinguishing between the real dreams and the counterfeits. That bothered me at the time. What more intimate lie can a person possibly tell herself? I would suppose forgetting which was which was me getting some sort of cosmic comeuppance, if I believed the universe worked that way. My forty-four years have yet to reveal any consistent, compelling evidence of justice woven into the fabric of this world.

I’m digressing. I’m stalling.

In the dream, Amanda and I were on the road in the same sky-blue PT Cruiser that brought Constance here from Gary, Indiana. Amanda was driving, and I was sitting in the backseat. At first, I didn’t know where we were. I’d been listening to her talk, watching as we passed an unremarkable procession of woods, pastures, houses, farms, roadside convenience stores, and gas stations. Then I remembered Amanda’s funeral, and I assumed the whole thing – her death – had been some sort of misunderstanding. I didn’t bring it up, but there was an indescribable sense of relief, that we’d all clearly been mistaken in thinking that she’d died of the overdose, or of anything else. I know that these sorts of dreams are not uncommon, encountering a loved one who has died and “realizing,” in the dream, that the person never actually died. But, to my knowledge, this is the first time I’ve had such a dream about Amanda.

She was talking about a difficult client, a bisexual woman with a thing for horses and centaurs and Kentau rides and so forth. The client wanted some elaborate set of photographs done, but hated the idea of photo manipulation and was insisting that as much be done with makeup and prosthetics as possible, because she wanted pictures of “something real, not fake.” In the dream, this was the last client that Amanda had before she killed herself. Or, rather, the last one before I’d only thoughtthat she killed herself. In the dream, this was the woman she slept with, and then lied to me about having slept with. And, in the dream, I clearly remembered having written “Pony,” in our apartment in Candler Park though, now, awake, I recognize that those memories were false. Also, the woman that Amanda was fooling around with wasn’t a client. She owned a sushi restaurant in Buckhead.

“It’s allfake,” Amanda said. “I toldher that. Either way, it’s all pretend. But that only seemed to make her more determined to have her way.”

And then we were walking together along a narrow wooded path, though I don’t recall our having stopped and gotten out of the car. It was very hot, and the air was filled with mosquitoes and gnats. I remember shooing away a huge bluebottle fly that had lighted on my arm. The path was familiar, even though it was someplace I’d not been since I was a teenager. It was the trail leading down to the flooded quarry in Mayberry where I used to collect trilobites, where I discovered Griffithides croweiiin 1977. I was very excitedly explaining all this to Amanda, and I said that maybe we’d get lucky and find another one of the trilobites before we had to leave. I was talking about crinoids and brachiopods, horn corals and blastoids, all the sorts of sea animals preserved in the hard yellow-brown beds of cherty limestone. There was a tropical ocean here then, I told her, three hundred and fifty million years ago, aeons before the coming of the dinosaurs, in an age when hardly anything ventured onto the land.

“Dear, you’re not paying attention,” she said.

And I realized then that we weren’tapproaching the nameless chert quarry in Alabama, but the granite quarry that is now Ramswool Pond. Soon, we were standing at the edge, staring down into what looked a lot more like molten asphalt than water. It was that quality of black, pitchblack, and seemed to my eyes to have the same consistency as hot tar. When I picked up a stone and threw it in, it didn’t vanish immediately, but lay on the surface for a moment before slowly sinking into the substance. There were no ripples. There was no splash, either. The surface of that pool was perfectly, absolutely smooth.

“I don’t think we should be here,” I told Amanda, but she sat down on a boulder and pointed into the morass spread out before us.

“Well, it wasn’t exactly my idea,” she said. “Isn’t this where you saw that girl drown herself?”

That’s something I never told Amanda about, the naked girl I’d seen (or thought I’d seen) that summer afternoon thirty-one years earlier. The beautiful girl whose hair I recall being as black as tar.

“Wasn’t her name Bettina?” Amanda asked. “The girl you saw drown, I mean. Didn’t it come out, that her name was Bettina. Wasn’t she alsosome sort of an artist?”

And then I saw something lying in a clump of weeds not far from us. Clearly, it had crawled out of the pool. It was still alive, but seemed to be in a great deal of pain, its skin entirely coated in the black goop from Ramswool Pond. Amanda said something, but I can’t remember what. I couldn’t take my eyes off the writhing thing on the shore. It had been a woman once. I could see that now – a female form discernible through the glistening, tarry ooze – but any finer features were obscured. She was dying as I watched, because the black stuff was very slowly eating her alive. It was corrosive, I think, like digestive fluids, and an oily steam rose from the body and lingered in the air.

“You don’t want to see this,” I told Amanda.

“My name is not Amanda,” she protested.

“No, but it’s what I call you when I write about you. You wouldn’t want me to use your real name, would you?”

“You use hers,” she replied, and pointed at the writhing mass in the cattails and reeds. “What the fuck’s the difference, Sarah?”

And then the thing in the weeds began to scream – a scream that gave voice to both pain andfear – as the black water ate deeper into its flesh. I took Amanda’s hand and tried to pull her to her feet. “We’re not supposed to be here,” I said.

She looked up at me, surprised, a guarded hint of a smile on her lips. And she said, “Turn not pale, beloved snail, but come and join the dance.” And before I could reply, the sun had gone down, and risen again, and set a secondtime. We were no longer at the edge of Ramswool Pond, but standing at Hobbamock’s altar stone with the red tree towering above us. And the moon was so full and bright I could see everything, and, too, there was a roaring bonfire somewhere nearby.

I know the ugly faces the moon makes when it thinks No one is watching.

I could smell the woodsmoke, and I could hear the hungry crackling of the flames. And all about the tree, but farther out from it than the place where Amanda and I stood, there was a ring of wildly capering figures. She told me not to look at them, just as I’d told her not to look at the dying thing from the pool, but I stole a glance. Justa glance, but it was enough to see that they weren’t exactly human. In the firelight, their hunched silhouettes were vaguely canine, and I said something to Amanda about the coyotes that Constance thought she’d been seeing hanging around the garbage cans. Then Amanda was reciting Edgar Allan Poe, and her voice was as fervent, as fevered,as the swirling, whooping, careening dancers:

And the people – ah, the people—

They that dwell up in the steeple,

All alone,

And who, tolling, tolling, tolling,

In that muffled monotone,

Feel a glory in so rolling

On the human heart a stone—

They are neither man nor woman—

They are neither brute nor human—

They are Ghouls —

And their king it is who tolls —

And he rolls, rolls, rolls,

Rolls

A paean from the bells!

And if I’m to believe anything that Charles Harvey wrote in his unfinished book, the serial killer Joseph Fearing Olney became obsessed with these same lines, writing them over and over in his journals and on the walls of his jail cell. He even wrote them on slips of paper that he would place inside the mouths, beneath the tongues, of the decapitated heads he buried at the base of the red tree. Beneath the tongues he had forever silenced.

In my dream, there was no wind. The air was as stagnant as whatever vile black vitriol had seeped up from the earth and filled in Ramswool Pond. But, even so, the branches of the ancient, wicked oak moved, swaying, creaking, scraping against one another, leaves rattling like dragon scales, as though a hurricane were bearing down upon the land.

“Two billion trees died in that storm,” Amanda said. “Think about it a moment, Sarah. Two billiontrees.”

“Not thisone,” I replied, gazing up into those restless boughs. “This one seems to have ridden out the tempest just fine.”

“Yes,” she said and smiled. “But don’t think that was all luck, Sarah. It took a lot of blood and sweat to keep her safe when that storm came tearing through. It has always taken a lot of blood and sweat, keeping her safe. Like all doors, she tends to swing open, and so care must be taken to mind the hinges and the latch.”

And I think I asked, “We aretalking about the oak?”

And I think that Amanda replied, “If that’s how you see her, yes, we’re talking about the oak.”

I forced myself to make notes in pencil, not long after I awoke, or I’d have lost almost all of this. But even so, I’m having trouble making sense of much of what I scribbled down, half asleep. Partly, that’s because most of the handwriting is illegible, and, partly, because a good deal of what I can read still refuses to yield anything like meaning. I know that I’m filling in some of the gaps. Making some of this up. Approximating. That therapist who wanted me to keep the dream journal, I told her I could not possibly remember my dreams verbatim, and being a writer, it was inevitable that I might invent things as I wrote them out. But she said not to worry. So, right now, I’m trying hard not to worry.

I stood with Amanda, at the altar beneath the red tree, and the dancers howled and skipped around us. Sparkling embers rose into the sky to meet a grotesquely swollen full moon. The moon was still low on the horizon, and only half visible above the tree. I would call the scene hellish,only, at the time, I don’t believe it struck me that way at all. Only my waking mind would render it hellish in retrospect, measured against my waking values and fears and preconceptions. Dreaming, I wantedto accept Amanda’s invitation and “join the dance,” that perverse “ring around the rosie” and whatever it might entail. I wanted to be initiated into the mysteries of the tree, or into the mysteries that the tree merely represented.

“What have you brought for her?” Amanda asked, and I felt entirely inadequate, standing there beneath the single glaring white eye of the moon. At first, I was certain that I’d brought nothing at all, no offering to lay upon the slab that I now understood must have been placed at the foot of this tree long before John Potter, long before the Narragansetts. Watching those giant branches moving against the backdrop of the moon and stars and the indigo nothingness of space, I didn’t need Amanda or Harvey or anyone else to explain to me that this ground was consecrated long ages before the Europeans came in their sailing ships, before tribes of nomads wandered across an icy spit of land connecting two continents. Before anyman stood here, and before any tree was rooted in this soil, the land was touched and claimed and set aside.

In the dream, I was wearing the ratty wool coat that Amanda finally gave to Goodwill so she wouldn’t have to see it anymore, so that I’d have to buy a new one. I reached into the coat and retrieved from an inner pocket several pages of Charles Harvey’s manuscript, rolled into a tight bundle and tied off with a piece of green fishing line. I held the pages out so that Amanda could see them.

“Well,” she said, still smiling, “that’s a start.”

“I would have brought more, but he never finished writing it.”

“He couldn’tfinish,” she said. “You cannot ever conclude what has no end. It’s like walking the circumference of a circle. You can only get tired and find some arbitrary place to stop.”

“Do you know how tired I am?” I asked her, and she said that she did, and then she took the rolled-up pages of typescript from my hands. I was glad to be rid of them. I remember, distinctly, being extremely glad that they were no longer my responsibility. And that was the sense I had, that they’d been a responsibility I’d shouldered for a very long time.

“Stop looking at the sky,” Amanda said. “You’ll go blind, if you don’t look away.”

And so, instead, I looked down at the altar stone, seeing clearly for the first time all the sacrifices painstakingly laid out upon or near the stone, or set in amongst the roots of the tree, or tucked into knotholes (I have always called these “Boo holes,” after Boo Radley in To Kill A Mockingbird). There were bloodier things than murdered rabbits, but I do not think it will serve this narrative to describe them in detail. Even that monster Joseph Fearing Olney would have felt himself inadequate before that banquet. And I knew it wasa banquet, that there would soon be a feast, of one sort or another.

“Hercules did not slay the child of Typhon and Echidna,” Amanda said, speaking very softly. She bent down and lifted a white votive candle from the altar stone. “In severing that immortal head, he only set the Hydra free, so that she could take her rightful place in the Heavens.”

“Echidna,” I said, and the word brought to mind nothing but those spiny little egg-laying mammals from New Guinea. Amanda nodded, and with the candle, she set the pages I’d given her on fire. Some of the ashes settled across the altar, while others rose upwards, like the embers of the bonfire, becoming lost in the swaying branches of the red tree.

And Amanda said to me, “And again she bore a third, the evil-minded Hydra of Lerna, whom the goddess, white-armed Hera, nourished, being angry beyond measure. . ” Then she paused, the flame having burned down very near to her fingertips, and she dropped the smoldering remains of my offering onto the stone with everything else. “Only, Mother Hydra was notevil-minded, though I well imagine Hera wasangry,” Amanda said, but did not bother to elaborate.

And around me, the dream moved like the tumbling colored beads or shards trapped inside a kaleidoscope’s tube, and I tumbled with them. The night passed away, and Amanda was replaced by Constance, and the scene at the tree by the attic of Blanchard’s farmhouse. The din of the dancing creatures was replaced by the commotion from the air conditioner, which was making much more noise than usual. Constance was sitting on her inflatable mattress, and I was sitting nearby in a chair. She said that she was pretty sure the AC was on its last leg, that it was about to blow the fan or an evaporator coil or something of the sort.

“I sounded like that the time I caught pneumonia,” I said, and she laughed.

“I thought you’d be at the tree,” she said, and jabbed a thumb in the direction of the oak. Bright moonlight shone in through the attic windows, and the same sort of votive candles that had burned at the altar were scattered about Constance’s garret. “I thought they’d have you out there for the festivities. Way I had it figured, Ms. Crowe, you’d be the guest of honor, or the main course.”

“Is it that sort of feast?” I asked, and she shrugged.“Wasn’t that how it went, when those boys caught up with Sebastian Venable beneath the blazing bone sky?

Wasn’t he finally devoured for his sins by vengeful Mediterranean urchins, while poor Catherine watched on?”

“That’s not how it ever seemed to me,” I said. “To me, it always seemed that Sebastian merely consummated his desires. He’d looked upon the face of god, when he and Violet took their cruise to the Galapagos Islands—”

“The part of the play with the predatory birds and the baby sea turtles,” Constance said, and I nodded.

“Sebastian was only seeking after release, having seen too much, and that day the boys at Cabeza de Lobowere only providing that release.”

“It means ‘head of the wolf,’ ” she said. “Cabeza de Lobo,”and I told her that I already knew that.

“Well, you’re a smart cookie. Not everyone would,” she replied, and then added, “But yes, I think it’s exactly that sort of a feast.”

“They never proved that Olney was a cannibal,” I said. “Not like old man Potter. They had no real evidence that he ate from any of the women he killed. And he denied it.”

This conversation, there was so much of it. It went on and on while the air conditioner wheezed and choked and sputtered. And at some point I realized that, while I was still wearing my old wool coat, Constance was completely naked. I hoped she would invite me into her bed again. She sat there like some heathen idol, some Venus made not of marble but living, breathing tissue. Her legs were open, revealing the wet portal of her sex, and she didn’t seem to mind that I stared, but, like Amanda, she warned that I could go blind, if I looked too long or too closely.

“I thought that only worked with masturbation and the sun,” I protested.

“Moonlight is merely reflected sunshine,” she said, “and every star is another sun.” Then, as I watched, her skin changed, or I noticed for the first time that it had been meticulously painted with a pattern of overlapping oak leaves. And, before my eyes, the painted leaves turned from summer greens to rich shades of red and brown. And they began to fall, slipping off her body and settling onto the mattress all around her. I remembered the kanji tattooed above her buttocks:

and for a while, I could only watch the spectacle of the leaves drifting down from Constance’s shoulders and breasts and face. It was too beautiful to turn away from, and like Harvey’s Quercus rubra,somehow too sublime, too terrible. I realized that the air in the attic had lost all its characteristic odors – turpentine, oils and acrylics, linseed oil, gesso, stale cigarette smoke. Now there were only the faintly spicy smells of autumn.