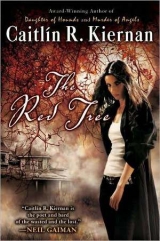

Текст книги "The Red Tree"

Автор книги: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Back then, I had blessed few points of reference, but now I’d point to any number of the Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian painters. Theyknew women with faces like hers, knew them or invented them. They set them down on canvas. In particular, I’d point to Thomas Millie Dow’s The Kelpie,which I first saw in college, years after that afternoon at the chert pit, and which still makes me uneasy.

When the water was as high as her chest, she must have reached a drop-off. The pit was at least a hundred feet deep, and the submerged walls were very steep. Most spots, it got deep fast. She took another step forward and just sank straight down, like a rock. There was a little swirl of water where she’d been, and then the surface grew still again. I crouched there, waiting, and I swear to god (now, there’s a joke) I must have waited fifteen or twenty minutes for her to come up again. But she never did. Not even any air bubbles. She just stepped out into the pit and sank. vanished. And then, suddenly, the stifling summer air, which had been filled with the droning scream of cicadas, went silent, and I mean completely fucking silent. It was that way for a few minutes, maybe. no insects, no birds, nothing at all. That’s when I realized I was scared, probably more scared than I’d ever been in my life, and a few seconds later the whippoorwills started in. Now, back then, growing up in bumblefuck Alabama, you might not learn about Pre-Raphaelite sirens, but you heard all about what whippoorwills are supposed to mean. Harbingers of death, ill omens, psychopomps, etc. and etc. Never mind that you could hear whippoorwills just about anysummer evening or morning, because the old folks said they were bad fucking juju. And at that particular moment, waiting for the naked, black-haired girl to come up for air, with what sounded like a whole army of whippoorwills whistling in the underbrush—“WHIP puwiw WEEW, WHIP puwiw WEEW, WHIP puwiw WEEW”—I believed it. I just started running – and this part I don’t really remember at all. Just that I made it back to my bicycle and was at least halfway home before I even slowed down, much less looked over my shoulder. But I never went back to the chert pit, not ever. It’s still there, I suppose.

So there, that’s my only “true-life” ghost story or whatever you want to call it. My Wednesday morning confession to this drugstore notebook. No doubt, I must have come up with all sorts of rationalizations for what I’d seen that day. Maybe the girl was from another town – Moody or Odenville or Trussville – and that’s why I’d never seen her before. Maybe she was committing suicide, and she never came back up because she’d tied concrete blocks around her ankles. Maybe she didcome back up, and I just missed it, somehow. Possibly, I was suffering the effects of hallucinations brought on by the heat.

And it’s raining even harder now. I can hardly see the slaty smudge of Ramswool Pond anymore. It’s lost out there somewhere in this cold and soggy Rhode Island morning. Days like this one, I have a lot of trouble remembering why the hell it was I left Atlanta. But then I remember Amanda and all the rest, and this dreary goddamn weather seems a small price to pay to finally be so far and away from our old place in Candler Park. Yes, I amrunning, and this is where I have run to, thank you very much. I put out a housing-wanted add on Craigslist, and one thing led to another, connect the fucking dots, and here I am, crappy weather, sodden groundhogs, and all. No regrets. Not yet. Boredom, yeah, and nightmares, and a dwindling bank balance, but life goes on. And now I have a hand cramp, so enough’s enough. Maybe I’ll just stick this notebook backin the bag from the drugstore, dump it in the trash, because right now, I truly wish I’d been content to sit here and drink my coffee and wait for the deer to come out.

9 May 2008 (Friday, 8:47 p.m.)

The thing I can’t seem to get around is the boredom. Or maybe I mean the solitude. Perhaps I am not particularly adept at distinguishing these two conditions one from the other. I didn’t have to plop myself down in the least populated part of the state. I could easily have found something in Providence or some place near the sea, like Westerly or Narragansett. Coming here was, I suppose, an impulse move. Seemed like a good idea at the time. And there’s TV and the internet (by way of two different satellite dishes, I’ll note), and I have stacks of DVDs and CDs, my cell phone and the books I brought that I’ve been meaning to read for. well, some of them for years. But I’ve been here two weeks, and mostly I just wander about the property, never straying very far from the house, or I drink coffee and stare out the windows. Or I drink beer and bourbon, even though that’s a big no-no with the antiseizure meds. I’ve taken a couple or three long drives through South County, but I’ve never been much for sightseeing and scenery. Last week, I drove all the way out to Point Judith. There’s a lighthouse there and picnic tables and a big paved parking lot, though, fortunately, it’s early enough in the season that there weren’t tourists. I understand they are like unto an Old Testament plague of locusts, descending on the state from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, other places, too, no doubt. The siren song of the fucking beaches, I suppose. I saw a bumper sticker during one of my drives that read “They call it ‘tourist season,’ so why can’t we shoot them?” And yet, I expect that all of South County and much of this state has, sadly, become dependent on the income from tourism. The curse is the blessing is the curse. But, yeah, I sat there at one of the tables at Point Judith, and I watched what I suppose were fishing boats coming and going, fishing or lobster boats, a few sailboats, headed into the bay or out to sea or down to Block Island. The gulls were everywhere, noisy and not the least bit afraid of people, and that made me think of Hitchcock, of course. The tide was out, and there was a smell not unlike raw sewage on the wind.

Yesterday, I drove up to Moosup Valley, which is a little ways north of here, much closer than either Coventry or Foster. I saw the library, but only went in long enough to grab a photocopied flyer about its history. I don’t like being in libraries any more than I like being in bookstores, and I haven’t liked going into bookstores since my first novel came out fourteen years ago. Here’s a bit about the library from the flyer: “The History of the Tyler Free Library began when the people of Moosup Valley acquired Casey B. Tyler’s private collection of about 2000 books and therefore needed to build a structure to house it. The Tyler Free Library was formally organized in January of 1896, and a Librarian was hired. The Library opened and fifteen cards were issued on March 31, 1900. Local residents organized the books and the Library was open on Saturday afternoons.” The flyer goes on to say that the rather austere whitewashed building was moved from one side of Moosup Valley Road to the other, north to south, in 1965. And why the hell am I writing all this crap down? Oh yeah, boredom.

I also stopped at an old store on Plain Woods Road, to buy cigarettes and a few other things. I’m smoking again, and that wouldn’t make my doctor back in Atlanta any happier than would all the whiskey and bottles of Bass Ale. Like just about everything else around here, the store is ancient, and like the library, it, too, bears the name of Tyler. I always heard all that stuff about how closemouthed and secretive New Englanders are, especially when you get way out in the boonies like this, and especially towards outsiders, but either the stereotype is false or I keep running into atypically garrulous Yankees. There was an old woman working in the Tyler Store, and she told me it was built in 1834, though the west end wasn’t added on until 1870. Most of what she said I don’t recall, but she did know (I don’t know how, some local gossip’s grapevine, I suppose) that I was the “lady author boarding out at the old Wight place.” And then she said it was such a shame about the last tenant, and when I asked her what she meant, she just stared at me a moment or two, her eyes huge, magnified behind trifocal lenses.

“You don’t know?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I replied.

“Then it’s not for me to tell you, I suspect. But you ask Mr. Blanchard. You got a right to know.”

I told her that Blanchard, the landlord, is away on some sort of farm-related business, a fertilizer convention or sheep-dippers’ conference or something of the sort, and that I wouldn’t be seeing him again for at least a week, and probably longer than that (he lives up in Foster and hardly ever comes out this way). But, no dice. She wouldn’t say more, and returned, instead, to the history of the old store, and a cider mill that used to be somewhere nearby, and something about the cemetery where her father is buried, and all that sort of thing. Local color. And I listened politely, deciding I shouldn’t press her regarding the former tenant, whatever it was about him or her I should know, that she felt I had a right to know. All Blanchard ever said was that a professor from URI rented the place before I came along, but I know it’d sat empty for more than two years.

Not long after I got back to the house, there was a phone call (because I forgot to turn off my damned cell), Dorothy wanting to know if I was settled in, how I was getting on out here, was I homesick, and, finally, when she could no longer put it off, had I made any progress on the novel. I almost hung up, because she knows I have not even startedthe goddamn novel. But, Dorothy is a good agent, and those don’t grow on trees, and I might still need her someday. She reminded me, tactfully, but unhelpfully, that publishers who have paid out sizable portions of sizable advances eventually expect manuscripts in return, no matter how much money I might already have made for them on my previous books. I could have lied and said the writing was going well and not to worry. But where’s the fucking point? The deadline is only six weeks off now, and that’s not the original deadline. That’s the extension on the original deadline, and so then we talked about the feasibility of a secondextension, say six or eight months. Dorothy gets this tone in her voice at times like that, and I feel like I’m a kid again, talking to my mother. But she said she would call my editor next week. At least she didn’t ask about my health. At least that’s something.

Oh, I finally unpacked my Waterman pens. I’m using the “diamond-black” Edson I bought in Denver last year. I have consigned the yellow pencil stub to a drawer. On a whim, I seriously considered burying the damned thing, but then I started worrying over whether the graphite (a form of carbon, I believe) would be bad for the earthworms and moles and such. I thinkI read somewhere that residual graphite is harmless, but I’ve already got enough on my conscience without having to worry about whether I’ve poisoned the grubs. I’ll do my best to keep making entries in this notebook. The pens make it much easier, and it’s not like I’ve got a hell of a lot else to do, is it?

11 May 2008 (7:29 a.m.)

I have been awake maybe twenty minutes, and the nightmare is still buzzing about my skull like a hungry swarm of mosquitoes. Nothing, though, that I can conveniently swat away. Also, I have misplaced my glasses, and, no matter how hard I squint, the blue college-ruled lines on this page shift and sway, grudgingly resolving for a few seconds at a time before they fade and blur again. Still, fuck the coffee, I’m going to get this down before I lose it. Last night, I read back over my two previous entries, and hell, they don’t even sound like me. They sound like some pale ghost of my voice. Not even a decent echo. What does a writer become when she can no longer write? What’s left over when the words don’t come when called? What did Echo become after she was slaughtered for spurning Pan, or after her collusion with Zeus was discovered and so she was punished by Hera, or after her rejection by Narcissus? Those pages seem, at best, my ownecho, a waning, directionless cry in this wilderness to which I have exiled myself. But, the dream. Write down the dream and save the rest for later. Write down what you can recall about the dream.

I was at the kitchen table, just as I am now, smoking and staring out at the shadows gathering as the sun set, the afternoon melting into twilight. I could see the dark smudge of Ramswool Pond, and the low, rocky hills around the farm, the trees pressing in, new-growth trees where once there were fields for grazing sheep and apple orchards and whatever else. I was sitting here, smoking, and the longer I watched, the more unnerving the shadows became, as the coming night drew them ever sharper. I felt as though they were becoming substantial, corporeal things, and that the sun’s retreat westward was releasing them from unseen prisons, below the ground or from out of unseen dimensions which exist, always, alongside this visible world. There were no lights on in the house, I think, and it had already fallen into darkness around and behind me, and that darkness seemed inhabited, populated by dozens of muttering men and women. I would try to make out what they were saying, but always their words slipped away from me. And all the while, I suspected the murmuring was meant to distract me from all that lay outside the kitchen window. With hindsight, I might even be so reckless as to guess that this intent was merciful. But, since I could not make head nor tails of the murmurers’ attempts at communication, I watched the window, instead. I realized here that I was not sitting in the kitchen of Mr. Blanchard’s old farmhouse, but in a small screening room, a movie theater, and the window was, in truth, a screen. It’s a cheap fucking trick, the kind of unimaginative, low-budget legerdemain at which dreaming minds seem to excel or in which they only compulsively indulge. I sat in my theater seat and stared out the window, which was now, of course, merely the projected image from concealed mechanisms hidden somewhere behind me, flickering moments fused to celluloid. The muttering voice had become other members of the audience, though I could not actually see any of them (and I am not certain that I tried). I don’t often go to the movies. But Amanda liked to, so she usually went without me. That was something else we might have shared, but I couldn’t be bothered.

On the screen, I see the kitchen’s window frame, and the fallow, overgrown land beyond, and I see the shadows growing bolder. And then I see you,Amanda, and you’re standing with your back to me, but, still, I know it’s you. You’re standing at the first of the stone walls, staring out towards the flooded granite quarry. Your shoulders are slumped, your head down, almost bowed, and you’re wearing a simple yellow dress, and even though you are too far away for me to make out such details, I can see that the fabric has been imprinted with tiny flowers of one sort or another, a yellow calico. Your long hair hangs down as though you wear a veil, and it’s matted and tangled, as if you haven’t combed it in days and days. That’s so unlike you, and I began, here, to suspect I was only dreaming, because you’d never be out with your hair in such a dreadful state, not out where someone might seeyou.

And then the deer are coming out of the shadows gathered beneath the trees, and there are other animals, though it’s hard for me to be sure what they are. Animals. Things smaller than the deer, things that move swiftly, mostly creeping along nearer to the ground. I think the deer are all coming toyou, that possibly you have called them somehow, and I think, for a second or two, I am delighted at the thought and wonder why you never told me you knew how to call deer. I think back on the stories you told me about your childhood in Georgia, that your father was a hunter, so I consider that maybe it was a talent you learned from him. And it occurs to me now that, a page or two back, I shifted fucking tense, past to present. I fucking hatethat, but I’m still so asleep and afraid I’ll forget something important – that I have already forgotten – if I wait and try to wake up before putting this down.

In the dream, I think the deer are being called to you, the deer and those other animals. But you do not raise your head to greet them, do not make any sign whatsoever to acknowledge their approach. And I think, Maybe she knows that would only scare them away.The movie has a soundtrack, though I think I only become aware of it as the animals approach. I can hear their feet crunching softly in the grass, can hear wind, and what I think might be you singing very softly to yourself. All this time my girlfriend could sing to deer, and I had no idea. How crazy is that? And before much longer, those nervous, long-leggedy beasts and their damp noses would be pressing in all about you, and in that instant you seemed to me some uncanonized Catholic saint. Our Lady of the Bucks and Does and Fawns. And here, I think, I am grown quite certain that I am dreaming, but it hardly seems to matter, because there you are, so perfect, and I need to see you, and I need to know what is about to happen.

And here, too, the dream shifts again, canvas and plywood backdrops swapped and costumes changed in a seamless, unmarked segue. Now it is some otherevening, and I am not in the kitchen of the rented farmhouse off Barbs Hill Road, and I am not in that anonymous theater, either. Amanda is with me now, and we are no longer divided by windowpanes or silver screens or time. I am telling her how sorry I am, how it’ll never happen again, and she’s on her knees, huddled on a sidewalk washed in the sodium-arc glow of a nearby streetlight. She holds a stick of chalk gripped tightly in her left hand, drawing something on the concrete at my feet. By slow degrees, I scrape up enough comprehension to see that what she’s making resembles the squares of a child’s hopscotch game, only instead of numbers, each square contains a line from the magpie rhyme, with the first square marked Earth. In the second she has written “One for anger,” and in the third “Two for mirth.” She is only just beginning to fill in the fourth square, the chalk loudly scratching and squeaking against the pavement, and as I talk she shakes her head, no, no, no. She will not listen, will not hear me, and it does not matter whether I am a liar or sincere, for we have already come to a place where actions have forever eliminated even the possibility of forgiveness and reconciliation.

“Three for a wedding,” she says.

And all the things that I said, I’ve lost those words, had forgotten them by the time I awoke. But in the dream I speak them with such a wild desperation that I have begun to cry, and still she shakes her head– No, Sarah, no.

“Four for a birth,” she says, and doesn’t look up at me. There are enormous, rumbling vehicles rushing and rattling by, neither trucks nor cars, precisely, but I only catch fleeting glimpses of them from the corners of my eyes, for I know they are abominable things that no one is meant to gaze upon directly. The air smells like exhaust and something lying dead at the side of the road, and “Five for rich,” Amanda says and laughs.

Her chalk breaks, splintering against the sidewalk, and again I am only sitting in the kitchen, in this same chair. Again, I am watching her as the deer and other animals approach from the cover of trees and lengthening shadows. Head bowed, she is still singing, her voice calling out clearly across the dusk. Every living thing perks its ears to hear, and the sky above is battered black with the wings of owls and catbirds and seagulls. And it is here that I realize, too late, that the deer are not actually deer at all. Their eyes glint iridescent green and gold in the failing day, and they smile. Those long legs, so like jointed stilts, pick their way through brambles and over stones, and your song invites them. Perhaps, even, Amanda’s song has somehow createdthem, weaving them into being from nothingness. Or no, not from nothingness, but fashioning them from the fabric of my own fear and remorse and guilt. Maybe they are only shards of me, stalking towards her in the gloom. I rise to shout a warning, but no sound escapes my throat, and my fists cannot reach the glass to pound against the window. They smile their vicious smiles, these long-leggedy things, and the house murmurs, and she is still singing her summoning, weaving song when, one by one, they fall, merciless and greedy, upon her.

Fuck it. Fuck it all to hell.

I know I’ll look back at these pages in a few hours, and all this will sound like nonsense. It’ll sound like utter horseshit. The sun will hang high and brilliant in the sky, and my only clear recollection of the nightmare will be what I have written down here. I’ll laugh at the foolish woman I have allowed myself to become, jumping at these shoddy specters spat up by my sleeping mind, then wasting good ink to consign them to paper. It will fade, and I will laugh. More than anything, I’ll be annoyed at that fucking tense shift. But, Sarah, this raises a question, one that I am still too asleep to have the good sense to avoid. If I can write about Amanda through a child’s allegorical, symbolic horrors, then can I not also bring myself to write about the truth of it? This dream and all those I haven’twritten down and likely never will, they are only a coward’s confession, indirect visions seen through distorting mirrors, mere “shadows of the world,” because I do not seem to possess the requisite courage to look over my shoulder and face my own failures. Is that who I have become? And if so, how long can I stand the sour stink of my own fear? And hey, here’s another question. Have I stopped writing, not because I no longer know what to write about, but because I know exactlywhat I need to be writing? They were always only me, the short stories and novels, only scraps of me coughed up and disguised as fiction, autobiography tarted up and disguised as figment and reverie.

Maybe I’ll have another long, long drive today. Maybe I’ll get into the car and head back to that lighthouse and those picnic tables overlooking Point Judith and the bay. Or I’ll fill up the tank and hit the interstate and not stop until I’m in Boston. I won’tdrive south and west, because that way lies Manhattan, sooner or later, and Manhattan has come to signify nothing to me but looming deadlines and impatient publishers. At any rate, enough of this. Lay down the pen and shut the hell up for a while. Give it a rest, old woman.

14 May 2008 (3:29 p.m.)

So, turns out, the poorhouse will be avoided just a little fucking longer. Dorothy called from Manhattan about an hour ago. I was in the bathroom, but heard my cell phone ringing here on the kitchen table. My backlist was just picked up by a German-language publisher, the whole thing, which will make for a tidy little advance. Lucky me. The check from Berlin should arrive just about the same time things start looking genuinely bleak in my bank account. I know she could hear the relief in my voice, because I’m lousy at hiding that sort of thing. No poker face here. Anyway, after the news, there was a moment of awkward silence, then an even more awkward bit of chitchat – how’s the weather, are you feeling well, etc. – before she asked the inescapable question. Never mind she’d just asked a few days back.

“Any progress with the writing?”

I’d offer to send her this notebook, but I don’t think that she’d appreciate the humor. What I wantedto ask Dorothy, but didn’t, is when we’re finally going to admit the truth to one another and stop playing this game of wishful thinking. The day will come. I see that now more than ever. The hour will come when she asks, and instead of making my usual excuses or dodging it altogether by changing the subject or making a joke of the whole mess, I’ll just tell her it’s not going to happen. Sorry. The well is dry, and sorry it took me so long to summon the courage to say so. Is that how it happens? How a writer stops being a writer?

Can it actually be as simple as a few words spoken into a cell phone?

I just read back over that last entry, the dream of Amanda and the animals and the game of hopscotch. I’m really not so glad I wrote it down. If I hadn’t, most of the damned thing would have faded by now. I’d recall very little beyond the mood that it evoked, that almost smothering sense of dread, and I wouldn’t be sitting here gnawing it over. Or sitting here while itgnaws at me. Have I come all the way to this musty old house at the end of the world to be whittled away by nightmares and obsession? Merely running from ruin to dissolution? I can picture those nightmares and memories as termites, or maggots, or some cancerous growth, slowly consuming me, bit by bit. And maybe I’ve done nothing but make myself more palatable.

16 May 2008 (9:47 p.m.)

I met Amanda Tyrell on Friday the 13th, at a party I didn’t want to attend, where I hardly knew anyone else in attendance. And it wasn’t just any Friday the 13th, but Friday the 13th in October 2006. For the first time since January 13th, 1520, four hundred and seventy-six years earlier, the digits in the numerical notation for the day added up to thirteen (1+1+3+2+6=13). By the way, there’s a tradition that on January 13th, 1520, Ferdinand Magellan reached the banks of the Rio de la Plata and proclaimed, “Monte vide eu!”It’s probably apocryphal, and I only know it because of the goddamn internet, which makes historians of anyone with enough motivation and intelligence to tap at a computer keyboard. But it all sounds rather prophetic, right? Sounds like I should have done the math, read the signs, and then wisely looked the other way. It’s easy to say shit like that in retrospect. Hell, at the time, all I knew was that it was Friday the 13th, and I found most of the people who’d shown up for this CD-release thing to be utterly loathsome. I knew a girl in the band, had once dated her, in point of fact, and that’s the only reason I was there. I didn’t even particularly care for the music, sort of a countrypolitan revival thing, the whole business trying much too hard to sound like Patsy Cline and Skeeter Davis and Jim Reeves. I was drunk, nothing unusual there (except that I was drunk on freebooze), and kept wondering if maybe I’d wandered onto the set of a David Lynch film, circa Lost Highway. Cowboy hats and twangy guitars and some stripper who could not only drink from a Budweiser can held between her grotesquely artificial breasts, but could then crush the can with those same great mounds of flesh and fat and silicone. “Monte vide eu,”indeed.

I sat there, brooding in the smoke and honky-tonk roar, the din of all those chattering voices and laughter, and Amanda was sitting on the other end of the sofa from me. She said she knew who I was, that she’d read The Ark of Poseidonand, what’s more, she hadn’t really liked it. And nothing gets me wet like literary rejection. And, too, I probably hadn’t been laid in the last six months. She was wearing this skimpy wifebeater A-shirt and jeans, and there was nothing the least bit artificial about her breasts. Though, honest to fucking god, it was the talk that got me, at least at the start. I mean, she just sat down and started telling me how I’d screwed up that novel, like I’d asked her opinion or something. She was smoking clove cigarettes and drinking Jack and Coke, and it amazes me now that I can remember either of those details, given it’s been two years, and I was very, very drunk at the time.

“I wouldn’t go so far to say that it’s overwritten,” she said. Well, no. I don’t remember precisely whatshe said, but that was the sentiment. “But it could have been a lot less wordy.” I do recall that she said wordy,and that she laughed afterwards.

“Is that a fact?” I might have asked, and maybe she nodded and took a drag off her cigarette.

“Also,” she said, “the shell in Titian’s Venus Anadyomeneis most emphatically not an oyster shell, but a scallop. And the painting was owned by John Sutherland Egerton, who was the 6th Duke of Sutherland, not by the 5th Duke of Sutherland.” And no, that’s not really what she said. I have no idea what she really said, but it was exactly that pedantic and irrelevant to both the theme and plot of the novel.

“Yeah? So, sue the copy editor,” I replied, and she laughed again.

“You ever even been to Greece?” she may have asked next, and I may have replied, “You’re an audacious little cunt, aren’t you?”

“Audacity,” she said (or let’s say she did). “Yeah, I am audacious. But, as Cocteau said, ‘Tact in audacity is knowing how far you can go without going too far.’ ”

“I think I must have missed the tact.”“Then you aren’t paying attention.”

I finished a bottle of Michelob and set the empty on the table beside the sofa. And she just sat there, smoking and watching me with those fucking gray-green eyes of hers, eyes like lichen clinging to boulders on Rocky Mountain tundra or alpine meadows, like something unpleasant growing in the back of the fridge, eyes that were cold and hard, but very much alive.

“Sorry about that,” I said. “I’m drunk. Drunk and confronted with tactless audacity.”

And then she smiled at me and said, “In every artist there is a touch of audacity, without which no talent is conceivable.”

“Oh, so you’re an artist?”

“Depends.”

“On what? On what does it depend?”

“On how one chooses to define art.”

I glanced towards the bar, wanting another beer, but lacking the requisite motivation to walk that far. Besides, she might leave if I got up.

“Who the hell said that, anyway?” I asked her. “ ‘In every artist there is a touch of audacity,’ I mean.”

“Disraeli,” she replied. “But you still haven’t answered my question, Miss Crowe.”