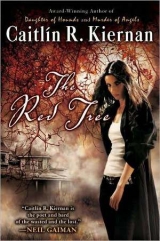

Текст книги "The Red Tree"

Автор книги: Caitlin Rebekah Kiernan

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

CHAPTER EIGHT

August 2, 2008 (9:12 p.m.)

I honestly believed I was finished with this journal. Over the past six days, I allowedmyself to start believing that. Certainly, I’ve wanted nothing more to do with it, or with Harvey’s manuscript, or that goddamn tree. And those six unrecorded days were remarkable only in their consistent, unwavering sameness. I read, watched television, and took a couple of long drives, one as far as Providence. Constance stayed in the attic, appearing only rarely, once more distant, and taciturn, and stained always with paint. I began to imagine this is how the remainder of the summer would proceed. And possibly the autumn, as well. Just yesterday, I sat here and thought how July seemed like some long, thoroughly ridiculous nightmare, but that now it was finally over. Two days ago, I packed Charles Harvey’s unfinished book back into its cardboard box and put it at the bottom of the hall cupboard, under some spare blankets. I had planned to do the same with his typewriter, but, for whatever reason, had not yet gotten around to it.

And then, late this morning, I opened the back door, the kitchen door (I can’t recall why), and found neon green fishing line tied about the porch railing near the bottom step. It was drawn taut, suspended maybe a foot above the ground, and led away into the briars and goldenrod and poison ivy, north, towards the red tree. I stared at it for a few minutes, I think. It seems now it took me a moment to fully process whatthe fishing line signified. I was startled that it was so very green, and couldn’t recall ever having seen that sort of fishing line before. And then I was shouting for Constance, and when she didn’t answer, I went back into the house. I went directly to the attic stairs. I knocked and asked her to please open the door. Then I tried the knob and discovered that it was locked. I banged on the door again, hard enough to hurt my knuckles. But no response came from the attic, and the door remained closed.

I very briefly considered breaking it down. I’m pretty sure that I couldhave, but then I admitted to myself that Constance was not behind the door. That she was not in the attic, or, for that matter, anywhere else in the house. Standing there on the narrow landing at the top of the stairs, in the darkness and the heat, I admitted to myself that the only place I would find her was at the other end of the length of green fishing line tied to the back porch. For a minute or two, I permitted myself the luxury of pretending that there was no way on earth I was going after her. It was only seventy-five yards, after all, from the house to the tree, and she’d taken precautions, done her little Hansel and-Gretel trick with the nylon line. If she’d wanted me along, she would have asked me. Constance Hopkins is a grown woman, and she can damn well look after herself. I thought each of these things, in turn, and then I retraced my steps and stared at the fishing line stretching away into the weeds and underbrush. I called her name a few more times, shouting loudly enough that people probably heard me all the way up in Moosup. And then, suddenly, the whole thing felt absurdly like a replay of the episode in the basement, and I stopped calling for her.

It was cloudy, and we haven’t had much of that this summer. Even so, the air was very still, oppressive, and I could tell the day was only going to get hotter. Even if it rains, I thought, the heat will only get worse.

I hesitated, lingering there on the porch, and then I took what I prefer to think was, realistically, the only course of action left open to me. I could hardly have called Blanchard or the police, could I? Even now, I don’t know what else I could have done, except maybe go inside and wait to see if she eventually found her way home. And I couldn’tdo that, even though that’s what I wantedto do. I’ve known Constance less than a month now, but, in that time, we’ve shared a bed, and we’ve shared the experience of living in this house on this godforsaken plot of land. I’d gone into the basement and brought her back. I’d washed the filth from her skin and hair, and she’d played nursemaid after my last fit and read Bradbury to me. More importantly, perhaps, we’d tried togetherto reach the tree, and togetherwe’d become lost, when getting lost was all but impossible. All this went through my head, I know, in only a matter of seconds, and then I left the porch and followed the trail of fishing line leading away from the house. I didn’t call her name again, and I didn’t look at the tree first. I just went.

I walked fast, and it took me hardly any time at all to reach the deadfall marking the halfway point between the house and the red oak. I discovered that the fishing line had been looped several times around one of the sturdier of the fallen pine branches, one that’s not so rotten. From there, it turned west, towards the fieldstone wall and the creek, just as I’d expected it to do. I stopped only long enough to catch my breath and wipe some of the sweat from my face. There was a tick crawling on my pants leg, and I flicked it away. Somewhere nearby, a catbird mewled and warbled, its voice sounding hoarse and angry. I looked up and spotted it, perched fairly high in the limbs of a small maple, and it occurred to me that from that vantage, the bird would likely be able to see both me and Constance. So, it could be fussing at either one of us, or both.

I followed the line through the wide breach in the stone wall, and then down the bank to the creek. Here, the nylon had been looped securely round and round the base of yet another tree, before continuing north again, following the stream a little ways. I disturbed a huge bullfrog hiding in a patch of ferns and skunk cabbages at the edge of the stream, and it jumped high into the air and landed with a splash, darting away into the tea-colored water. The ground is pretty soft down there, quite muddy in places, and my shoes left very distinct prints in the mossy soil. But mine were the only prints I saw. The only human prints (I think I also saw a raccoon’s). Somehow, Constance had walked over the very same ground as me and managed to leave none at all. Sure, she might weigh a few pounds less, but not enough that she wouldn’t have left behind footprints. Anyway, I soon found the next tree that had been used to anchor the fishing line; it turned east, heading straight back up the steep bank on the far side of the deadfall. I decided that I’d find Constance first; she had to be close now. I could worry about the missing tracks later on.

The bank was more difficult to climb than I remembered it being, or I was more careless, and twice I slipped and almost tumbled backwards into the stream below. The second time, I scraped my left elbow pretty badly. In the confusion, I briefly lost sight of the fishing line, but immediately spotted it again at the top of the bank. It had been wound about the base of another white pine, and now resumed its path north, leading me directly to the red tree.

Whatever distorting force or trick of distance had prevented Constance and me from reaching it on the sixth of July did not repeat itself. Other than my growing sense of dread, and the fact that I couldn’t find her footprints at the creek, there was nothing even the least bit disquieting or out of the ordinary about the walk from the back porch to the oak. And I suspect maybe I was beginning to let my guard down. I found the end of Constance’s lifeline tied to a sapling maybe ten feet away from the red tree. The plastic spool that had held the fishing line was lying nearby, and I picked it up. It’s lying here on the kitchen table as I type this. McCoy “Mean Green” Super Spectra Braid, thirty-pound test, eight-pound monofilament diameter, 150 yards. I suppose she picked it up on one of her trips into Moosup or Coventry or Foster. It hardly matters. The label on the spool reads, “Soft as Silk, Strong as Steel.” Part of the price tag has been pulled away, but I can still see that the spool cost $14.95.

These details mean nothing, I know. I knowthat. I am only trying to put off what came next. That is, I’m only putting off writing it down. Consecrating it in words. But it is sosimple. I’d bent over to retrieve the spool, and that was when I saw the spatters of blood dappling the dead leaves, and also dappling the living leaves of creeper vines and ferns and whatever else grows so near the base of the oak. The blood was thick and dark, and had clearly begun to coagulate, but was not yet dry. And what still seems very strange to me – seeing it, I didn’t get hysterical. I didn’t freak out. In fact, I felt as though some weight had been lifted from my mind, a weight I’d carried for a long, long while. Maybe, it was only relief, relief that, seeing the blood, I no longer had to wonder ifsomething was amiss. I can’t say. But I looked up, towards the gnarled, knotted roots of the enormous tree, its bole so big around that three large men could embrace the trunk and still have trouble touching fingertips. And spread out above me, its heavy, whispering boughs, raised against the cloudy sky. And, even though I’d seen it up close once before, and dozed in ignorance beneath its limbs, I looked upon it now as though I was seeing the red oak for the first time. And I wondered how I ever could have mistaken it for anything so uncomplicated and inconsequential as a mere tree.

There’s a passage from Joseph Conrad that says what I felt in that moment far better than I can possibly hope to articulate on my own. Maybe it’s cheating, cadging the words of another author because I find myself wanting, inadequate to the task at hand. I just don’t care anymore. We could not understand, because we were too far and could not remember, because we were traveling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign – and no memories.Or, again, Thoreau’s “Earth of which we have heard, made out of Chaos and Old Night.” Or, finally, in my own faltering language, here, before me, was all time given substance, given form, and the face of a god, or at least a face that men, being only men, would mistake for the countenance of a god.

There was a great deal more blood. And something broken lying on the stone slab at the foot of the tree. I made myself look at it. It would have been cowardice to turn away, and I hope I can at least say I am not a coward. The rabbit’s throat had been cut, and its belly torn open. The wet, meaty lumps of organs and entrails decorated old Hobbamock’s altar, and there were also a few smears of blood on the rough, reddish-gray bark of the tree itself. My legs felt weak then, and though I don’t actually recall having sat, I remember standing up again sometime later. I cannot say how long I rested beneath the tree, gazing into those gigantic branches, making my eyes return again and again to Constance’s sacrifice. It may have been as long as an hour. It may have been only half that. By the time I left, the dead rabbit had begun to attract a cloud of buzzing flies, and I understood that the insects, and the maggots they heralded, were also there to serve the tree, in a cycle of life and death and rebirth that I could only dimly comprehend.

Whatever drove Joseph Fearing Olney to murder all those women and then bury choice bits of them beneath the oak, and whatever had finally driven John Potter insane centuries before – whatever it was that had taken Susan Ames and then her husband, and whatever malignancy had at last left Charles Harvey with no choice but to end his own life, I sat there before it, clutching the empty plastic spool that had recently held 150 yards of fishing line. I was sure that the tree would not allow me to leave. Or that, having seen it stripped of any pretense at being merely a tree, I would find myself incapable of walking away. Here was my burning bush, or the Gorgon’s face. Here was epiphany and revelation and, if I so desired, the end of self. So many had been undone before me, and I knew that secret history, and now I also knew the whyof the thing.

But I did find the requisite will to leave the tree. Or it allowed me to leave. I’ll likely never know which, and, likely, it makes no difference.

By the time I got back to the house, it was a quarter past two in the afternoon. I could hear Constance moving about upstairs. I considered trying, again, to get her to open the attic door, and I wondered if we’d passed one another somewhere in the woods. If she’d been headed back, following some alternate route to the one she’d marked with the fishing line, as I was picking my way towards the tree. I wondered where she’d gotten the rabbit. And then I went to the bathroom, undressed, searched my skin and hair for deer ticks (there were none), and took a hot shower.

I still have not seen Constance. I have not heard her come down the stairs. But I was in bed early last night, utterly exhausted, and then I slept late. She might have come down then. She might have stood in the doorway of my bedroom, watching me dream and trying to decide what is to become of the both of us, and by whose hand. She did a messy job on the rabbit.

August 3, 2008 (3:29 a.m.)

Three things.

First, about half an hour ago I reached into the front right pocket of my jeans and discovered there a section of jawbone, maybe two and half inches long, sporting two molars. That the jaw is human is undeniable. One of the teeth even has a gold filling. The bone is stained a dark brown, and there is clay and soil packed tightly into various cracks and into both the severed ends, partially clogging the porous interior. I held it awhile, as the initial shock faded, turning the fragment over and over in my hands, straining in vain to remember having picked it up and put it into my pocket. Then I stopped trying, and set it on the kitchen table next to the typewriter. I assume,in the absence of any other viable explanation, or any evidence to the contrary, that I must have discovered this scrap of jaw while sitting beneath the tree yesterday. That I must have picked it up (and maybe, when I found it, the bone was even still half buried in the ground), dusted it off, and then slipped it into my pocket. The fact that I remember doing none of these things does not strike meas having any bearing, any relevance, on whether or not this is actually what transpired.

Sitting, staring at that dirty timeworn piece of bone and the two dingy teeth still plugged tightly into their sockets, I thought about going to the closet and retrieving Harvey’s manuscript, so I could read back over the circumstances of the Olney killings. But I didn’t. I put those pages away, and I mean them to stayput away. Regardless, I recall the peculiarities surrounding the recovery of the decapitated heads and other skeletal remains that, between 1922 and 1925, the murderer had buried around the base of the red tree. Chiefly, that not all of the heads could be located, despite the fact that Olney had, in his journal, gone so far as to draw a map of the area around the oak, indicating each spot where he’d deposited bits of his victims. And, also, that all the heads that wererecovered, even those of the most recent victims, impressed the medical examiner handling the case as having been in the ground much longer than Olney claimed. No trace of flesh or hair was left, and Harvey writes that the coroner commented that the bone looked more like what one would expect from the excavation of an Indian grave, hundreds of years old, than from a recent burial. There was some speculation, at the time, that the earth below the tree might have been unusually acidic, or more amenable to some sort of grub or insect that may have picked the bones clean. We call this clutching at straws. And now I’m typingthese words, these sentences, these paragraphs, stating it all plainly in black and white, and it looks more absurd than just about anything else I’ve written down since coming to Rhode Island and first laying eyes on the tree.

And, as long as we’re talking absurdities, the more I stare at the chunk of jawbone from my pocket, the more I think about tales of fairy gifts. Or, rather, the perils of accepting any manner of food or drink or gift while within the perimeter of a fairy circle. The base of the tree is round, and so many people have drawn circles about it, repeatedly making of it a mystery (to once again paraphrase Joseph Campbell), or merely underscoring the mystery it has always been. Olney swore that these hills were hollow.

Constance made her offering yesterday, and, shortly afterwards, I sat beneath the heavy green boughs, marveling at the “face” of gods laid bare. And now I find that I came away with a grisly souvenir that I cannot recollect having found, much less having decided it would be a good idea to bring backwith me.

And here’s the second thing.

Reading my last entry, I see that twice now, since I began keeping this journal, I have written of experiencing epiphany in the presence of the red tree. Indeed, the second instance seems like little more than a revision, a better-worded second draft, of the first instance (July 6, 2008 [10:27 p.m.]). In its own way, I find this repetition as inexplicable and jarring as the jawbone from my jeans pocket. Or “Pony.” Back in July, when we tried to reach the tree and failed, I firstsaw the tree for what I now believe it to be. I wrote, “. . it seemed to me morethan a tree. . I saw wickedness dressed up like a tree.” But, then, in an entry I made only a few hours ago, writing of my latest trip to the oak, I wrote, “I looked upon it now as though I was seeing the red oak for the first time. And I wondered how I ever could have mistaken it for anything so uncomplicated and inconsequential as a mere tree.” Also, in both cases, I attempt to illustrate or elaborate on my revelation with a string of metaphors and similes.

Now, if the first “epiphany” were genuine, it would preclude the occurrence of a second, would it not? And if my narrative is to be trusted – if my goddamn memoriesare something upon which I can continue to rely—then I must find some way to account for and reconcile this redundancy. And it isa redundancy. I don’t see how mere forgetfulness could ever possibly account for this repetition.

Finally, a thought has occurred to me, and maybe it’s not the sort of thought I should write down. But I probably shouldn’t be writing anyof this down, so, fuck it. I have begun to question my assumption that Constance used the fishing line so she’d be able to find her way back. Sure, I know how rattled she was by our having gotten lost, trying to reach the tree in July. And then her misadventures in the cellar. But she clearly did notuse the line to get back to the house. She took some other route. So, possibly it was put there not as a lifeline, but as a means of leading meto the oak. A carrot on a stick. A trail of breadcrumbs left for a hungry animal to lap up. I’m moving the typewriter into my bedroom, away from the kitchen window. I’d rather not sit here now.

August 3, 2008 (4:57 p.m.)

It’s raining today, a hard, steady rain, and there’s wind and thunder and lightning. It’s coming at us from Connecticut, I think, and before that this storm must have seen New York, and Canada, perhaps. Maybe it was born in the Arctic, and has spent weeks looking for the sea. Upon reaching the Great Lakes and realizing they were landlocked, perhaps it felt cheated. If a tree can be wicked, surely a storm can feel betrayed. Anyway, I’ve spent most of the day shut away in my room (leaving only to go to the toilet), reading and trying hard not to think my own thoughts, trying only to lose myself in what others have thought before me. But somehow, as though escape from morbid rumination has now been forbidden, I ended up with Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. I’d meant to read something harmless, something new, the sort of throwaway paperback that commuters buy at airport newsstands, intended only to amuse or distract them for the duration of any given flight. Instead, I reread “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Gold Bug,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and “MS. Found in a Bottle.” There are two passages from the latter I wanted to write down, because they seem to speak not only to what I experienced yesterday, upon reaching the end of Constance’s tether and finding myself at the red tree, but also because they say something, I believe, about my present state of mind:

A feeling for which I have no name, has taken possession of my soul – a sensation which will admit of no analysis, to which the lessons of by-gone times are inadequate, and for which I fear futurity itself will offer me no key. To a mind constituted like my own, the latter consideration is an evil. I shall never – I know that I shall never – be satisfied with regard to the nature of my conceptions. Yet it is not wonderful that these conceptions are indefinite, since they have their origin in sources so utterly novel. A new sense – a new entity added to my soul.

Of course, Poe’s narrator, marooned on that ghostly black galleon as it sails the south polar seas, is a man bereft of the capacity for fancy and imagination. As he says, “. . a deficiency of imagination has been imputed to me as a crime. .” And here Iam, a woman afflicted since childhood with far too greata proclivity for fancy. At least, this is the judgment that was passed upon me at a very early age. All those elementary schoolteachers and aunts and my parents and whoever the hell else, those wise adults in Mayberry who fretted about and pointed at my “overactive imagination.” But I suppose that I’ve shown them. Well, then again, considering the lousy sales of my books, maybe they get the last laugh, after all. And maybe it is just those sorts of minds, closed as they are to the corrosive perils of fantasy, that are most suited to encounters with the uncanny. I can only say that Poe’s words ring true. Here is another passage from the same story:

To conceive the horrors of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions, predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge – some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.

August 3, 2008 (8:28 p.m.)

Not long after I made that last entry, as I was beginning “The Cask of Amontillado,” Constance knocked at my bedroom door. I said that I was busy, that I didn’t wish to be disturbed. It was a lie, on both accounts, but, still, those are the words that came out of my mouth.

“I heard the typewriter,” she said, her voice only slightly muted by the wood through which it had to pass to reach my ears. “So, I was surprised when I came downstairs, and saw you weren’t in the kitchen. I was surprised that the typewriter wasn’t on the table. Are you okay, Sarah? Is something wrong?”

I almost asked if she’d noticed the plastic spool lying near where the typewriter used to sit, the empty 150-yard spool of McCoy “Mean Green” Super Spectra Braid. But I didn’t. If I wasmeant to find that line and follow it to the oak, then we are playing a game now, the sort where one does not show her hand. And if I was not,it would have been an odious thing to say. There’s the worst of this, right there. Not knowing if I am consciously being led down these abominable and numinous roads. Or if we are both adrift on the same black galleon, in the same icy sea. Are we now damned together, or might I be the oblation that will set her free? Has she struck a deal with the tree, her life in exchange for something more substantial than a gutted rabbit? And if that’sthe truth of it, was the fishing line an attempt to warn me?

“I’m worried about you,” she said.

The door wasn’t locked, and I told her she could open it, if she wanted. She opened it partway, and peered in.

“There’s no need to be worried,” I replied. “I’m fine.”

I was sitting on the floor at the foot of the bed, and she was standing in the doorway. I was wearing only my bathrobe and a T-shirt and panties underneath it. She was wearing black jeans and one of her black smocks, and her hands and arms and face were a smudged riot of yellows and browns, crimson and gold, orange and amber and a vacant, hungry shade of blue, as though she’d begun, prematurely, to bleed autumn. Dr. Harvey’s antique Royal was (and still is) parked on the dressing table.

“Sarah,” she said, “has something happened? After the seizure, or because of it? Something I should know about? Or maybe when we were in the basement—”

“Do you remember it now, the basement?” I asked, and she stared at me a while before answering.

“Nothing I haven’t told you already.”

“Irgendwo in dieser bodenlosen Nacht gibt es ein Licht,”I said, not meeting her eyes. “Has that part come back to you?”

“Sarah, I don’t even remember what that means, what you toldme it means.” And she took a step or two into the room, though I’d only given her permission to open the door, not enter.

I shut my eyes and listened to the rain peppering the windowpanes, the one in front of me and the one on my right, south and west, respectively. I wished that she would leave, and I was afraid that’s exactly what she was about to do. I could hardly bear the thought of being alone, so near to the oak, but her company had become almost intolerable. So, there’s me between a rock and a hard place. Scylla and Charybdis. The devil and the deep blue sea. The fire and the frying pan.

“If you need to talk, I can listen,” Constance said.

“But you’re so busy,” I told her, and if I’d had my eyes open, I think I would have seen her flinch. “So much canvas, and so little time, right? That muse of yours, she must be a goddamn slave driver.”

“Sarah, are you pissed at me? Have I done something wrong?”

“Not that I’m aware of,” I answered. “Is there something I might have missed?” I opened my eyes, then, and I smiled at her. I wanted to shut the fuck up and not say another single word, and I wanted to take back what had been said already. I was sitting there – detached, dissociative– watching Constance, listening to the madwoman who’d hijacked my voice. In that fleeting instant, it seemed so perfectly crystal clear that I’d entirely lost my mind. But then the comforting certainty dissolved, and I could notdismiss the possibility that the madwoman – despite, or because of, her madness – might be wholly justified in her apprehensions.

“Not that I’maware of,” Consytance replied. Her voice had become wary, and she glanced over her shoulder, back towards the hallway and the kitchen. And the cellar door, of course, which lies in between the two. When she turned to face me again, the corners of her mouth were bent downwards in the subtlest of frowns.

“You must miss Amanda terribly,” she said. There was not even a hint of anything mocking or facetious in her voice. There was no sarcasm. But, still, there was that wariness.

“Didn’t I already tell you that Amanda is none of your concern?” I asked her. Or what I asked was very similar. Typing this, I am once more forced to admit that much of these recollections are approximations. Necessary fiction. My memory does not hold word-for-word, blow-by-blow transcripts. Very few minds are capable of such a feat, and mine doesn’t number among them. To again quote Poe (from The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket):

One consideration which deterred me was, that, having kept no journal during a greater portion of the time in which I was absent, I feared I should not be able to write, from mere memory, a statement so minute and connected as to have theappearance of that truth it would really possess, barring only the natural and unavoidable exaggeration to which all of us are prone when detailing events which have had powerful influence in exciting the imaginative faculties.

I’ve had more than one heated “discussion” with readers and other writers regarding the use of unreliable narrators. I’ve seen people get absolutely apoplectic on the subject, at the suggestion that a book (or its author) is not to be faulted for employing an unreliable narrator. The truth, of course, is that allfirst-person narrations are, by definition, unreliable, as all memories are unreliable. We could quibble over varying degrees of reliability, but, in the end, unless the person telling the tale has been blessed with total recall (which, as some psychologists have proposed, may be a myth, anyway), readers must accept this inherent fallibility and move the fuck on. Have I already mentioned the crack someone at the New York Times Book Reviewmade about my apparent fondness for digression? Consider the preceding a case in point.

Whatever specific words I might have used, I made it plain to Constance I did not wish to discuss Amanda.

“She was a painter, too,” Constance said, as though she hadn’t heard me. And it wasn’t a question, but presented as a statement of fact.

“Not exactly,” I said, wishing like hell that I had a cigarette, but I was out, and I wasn’t about to bum one off Constance.

“How do you mean?” she asked, and took another step into the room. The paranoid woman sitting at the foot of my bed noted both the physical incursion being made and Constance’s refusal to drop the obviously prickly matter of Amanda. “She didn’t paint?”

“Not with brushes,” I said. “Not with tubes of paint. At least, not usually. She used computers.”

“Graphic design?”

“She called it photo-montage,” I told Constance, who nodded and glanced at the typewriter on the dressing table. “She created composite images from photographs.”

“Oh,” Constance said. “Photoshopping,” and whether or not she’d meant to attach any sort of derisory connotation, that’s how the paranoid woman at the foot of the bed received the comment. And it triggered in me something that had not been triggered for quite some time, and I found myself needing to defend Amanda.“It was amazing, what she did,” I said, sitting up straighter, keeping my eyes on Constance. “She made photographs of things that couldn’t bephotographed.”“Right,” Constance nodded, looking at me again. There was no trace of malice in her distant sangría eyes. “I had a course on photo manipulation in college. But I’m not a photographer, I’m a painter.”