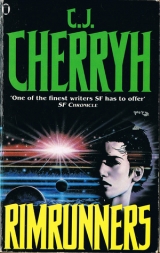

Текст книги "Rimrunners "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Doing just fine until they got to Engineering and Bernstein met them with: "Yeager, Mr. Orsini wants to see you."

"It's all right," she said to NG, and touched his arm. "I know what about. No problem."

"What?" NG asked her point-blank, delaying her at the door. "Fitch?"

"They're just trying to figure out some things." Best lie she could manage. "Fitch won't lay a hand on me. You can believe it."

So she checked out of Engineering before she'd even checked in, didn't say a thing to Bernstein about last night, and Bernstein didn't say anything to her.

Probably Bernstein and Orsini had talked. Orsini and the captain would have. Maybe the captain and Fitch—last night, his day, after she had left.

So she went up-rim to Orsini's office, she sat down and she got what she thought she would, question after question, while Orsini took notes on the TranSlate.

Nossir, nossir, yessir, nossir, I don't know anything about ops, sir.

At least Orsini didn't act as if hewas out to kill her.

"You have a problem with Mr. Fitch," Orsini said.

"I hope not, sir."

"You have a problem," Orsini said.

"Yessir."

"I trust you won't be stupid about it."

"I don't plan to be, sir."

Orsini gave her a long, long look. And started asking other questions, the kind she didn't want to answer.

Specific detail, on Africa, on her cap, what she carried, how many she carried—

I don't know, she said sometimes. Sometimes she shied off, inside, but she couldn't do that—had to make the jump, finally, and be Loki's, or not, and talk or not.

What can I tell them that Mallory couldn't? Hell, they got a renegade Fleet captain giving them any cap they ask. What's anything I know worth, against that!

So she answered, sat there telling things that might help kill her ship, one little detail and the other and deeper and deeper—far as a belowdecks skut could betray her ship, she did that—

Because here was here, that was what she kept telling herself. Because the war was lost, whatever it had ever been for, and Teo was dead, and the ship she was on was all that had to matter anymore—

Nothing to go back to. Pirates, people called the Fleet now. Maybe that was so.

"War's over," Orsini said. "There's nothing Mazian can win. Not in the long run. Just pointless destruction. Just more casualties. Best thing Mazian could do for his people is come in, sign the armistice—take what he's got coming and save the poor sods on his ships. But he won't do that."

She saw the docks again, being stationside, permanently, doing station scut, if they didn't do a wipe on you and leave you too schiz to defend yourself. Or there was Thule, maybe, one damn great hole they could dump all Alliance's problems into, same as they'd dumped Q-zone.

Hell if they'd come in. Hell if they would.

"Let's get specific again," Orsini said, and she didn't want to, didn't want to talk for a while, kept thinking about Teo and wondering if Bieji was still alive on Africa.

Bieji'd give her one of his black looks and tell her no hard feelings, but he'd try to blow her ass away.

Stay alive, Junker Phillips used to yell, stay alive, you stupid-ass bastards, I got too much invested in you—

"Yeager?"

"Yessir," she said. Here and now again. This ship, these mates.

Nothing personal, Bieji.

She sat there finally, throat sore from talking, Orsini note-taking again.

She thought, What I've done, there's no halfway, is there? Can't betray these mates, andthem.

She wanted to go somewhere and take a pill for her back and her head, she wanted to have a bath and see NG's face and Musa's and be back in rec with her shift, and remember why she wanted this ship. Right now she couldn't, right now she couldn't remember anything but Africa, couldn't see anything but Bieji and Teo and how it had been—

But those had been the good years. Those were the years before she'd lived off Africa, before she'd seen Ernestine, been from Pell to Thule and wherever they were now—

–older, maybe. Tired. Maybe just taking any out better luck might give her. She wasn't sure, unless she could feel what she felt on this ship again and shake the devils Orsini called up.

Orsini put down the stylus and got up from his desk, going to send her back down to Engineering, she thought: there was still time enough before the shift change.

God, she had to go back and go on pretending there was nothing wrongc

Had to tell NG somehow—before he found it out from somebody else.

"I want to show you something," Orsini said, motioning to the door.

"Sir?"

He didn't answer that. He showed her out, up-rim toward the bridge, to a stowage locker. He opened the door and turned on the lights.

Like so many corpses, pale, fire-scarred body-shapes stood belted to the left wall.

Armor.

Africa, one stencil said. Europe, the other. And names.

Walid—M. Walid.

Memory of a small, dark man, grinning. Always with the jokes.

Godc

Orsini was looking at her. She walked into the locker, laid a hand on the one rig.

"Knew this man," she said. And then, afraid Orsini would read a threat into that:

"Acquaintance, anyway."

"Collected it at Pell," Orsini said.

"You could've got mine," she said. "Left it there."

"Maybe your friend was lucky."

She shook her head.

"They're not in good shape," Orsini said. "Figured to use them in emergencies: figured they were free, why turn them down? Lifesupport halfway works, most of the servos operate on that one—it'll move, at any rate, but nobody's got time to fix it."

"Not real comfortable," she said, thinking, God, the damn fools, with a gut-deep memory of what a human joint felt like with a servo pushing it just a little past reasonable, wondering if Mallory who must've let them have the rigs had ever provided the manuals. She touched the surfaces, tried the tension in the arm, felt her stomach upset at what was going on in her brain, all the old information coming up like pieces of a disaster—parameters, connections—

–her hands were close to shaking. It was Africa'sgut, the armor-shop, the voices she hadn't been able to recall, the smells and the sounds—

"Fixable?" Orsini asked.

"Yessir," she said, and looked at him, trying to see the white plastic lockers and Orsini's face, not the gray, echoing space she remembered. She said, knowing nobody gave a damn, "But I don't want to."

"Why?"

I don't want to handle this stuff again. I don't want to think about it—

She said, realizing she had stirred suspicion, "Thought I was through with rigs like this." Then another reason hit her, in the gut. "And I don't want people to know where I come from."

Orsini said, quietly: "Can you get these things working right?"

"Yessir, probably."

Man wasn't paying attention, man didn't care. She didn't expect otherwise.

"No need to have it general knowledge," Orsini said. "We're insystem, slow rate, going to dock here and fill. You can make it back and forth up the lift. You've got enough level deck here."

She looked at the L by the entry, thought about what she could get to in the shop.

"Yessir." Without enthusiasm. It was in-dock work he meant and no liberty. But she hadn't really expected one, under the circumstances. "Not real easy. But I could do that."

"Not all crew gets liberty," Orsini said. "Takes five years' seniority. And the captain's approval."

"Yessir."

"You might eventually get a posting out of it," Orsini said. "If you have the right attitude."

She stood there thinking, Right attitude. Hell. And thinking that the mofs could think they owned these rigs, but you didn't just suit up and have everything work. She didn't say, Who am I supposed to fit this for? and explain that part of it; or think she had to say something if Orsini didn't.

Maybe Orsini would call that a bad attitude.

She just said, "I'll see what I can do, sir."

CHAPTER 23

THE NEWS about their heading into dock was on general com when she headed back for Engineering, forty-odd minutes to shift-change.

"Everything all right?" Bernie asked, asking more than that, she reckoned, and she frowned at him, just not able to come back from it and knowing she had to—had to put a decent face on things and not do anything that could make Bernstein wonder about her, because Bernie was watching, Bernie was going to be making regular reports to Orsini and Wolfe and maybe Fitch, and she knew it. You asked a body to be a turncoat and you'd better keep an eye on them, if you had any respect at all for them.

Damn right, sir.

Nor trust them if they smiled at you.

She said, "Wasn't a real good time, sir."

Bernie looked sad at that. But at least he didn't frown back at her.

"Anything the matter?" NG said—NG the first one to come up to her, on his own, when you never used to get NG out front on anything.

She said, thinking fast, "Looks like I don't get a liberty."

It wasn't what NG had worried about, for sure. He looked upset, touched her arm.

"Hell, I never have had. I'llbe here."

Got her right in the heart. She couldn't think for a second, couldn't remember what she'd decided two beats ago her story was, or put any organization in her thoughts.

NG'll be on board. Him and me. God.

"You didn't expect it," Musa said, from beside her.

"Dunno, didn't think, till they made the announcement; and Orsini told me it was five years. Shit, Musa—"

She didn't want to think about months and years. A week was hard enough, NG bound to ask what she was doing topside while they were in dock, or why Orsini had her out of main Engineering, going back and forth between the shop and topside.

Damn!

Musa gave her a hug around the shoulders, friendly, Bernie didn't mind a little PDA, NG didn't say anything else, back in his habit of no-comment, and she tried to cheer up, which she reckoned made it a tolerably good act.

Damn, damn, and damn.

They did a burn before shift-change, they started doing others, after.

" We'll be docking at Thule Stationc" Wolfe said on general address.

She felt sick at her stomach.

Wonder if Nan and Ely are still there. How long've we been out, realtime?

She counted jumps they had made, figured maybe as much as a year, stationside.

She stowed everything she wouldn't need, stuffed a duffle with things she would, same as those who were going stationside—"Hard luck, Bet," people dropped by to say, and some few of them, McKenzie included, were cheeky enough to say, "Yeah, well, but you and NG got free bunks and all the beer aboard.—Want me to buy you anything?"

She checked with the purser's office and found out she could draw on her liberty money even being held aboard, and that NG was downright affluent, never having used his liberty credits except for on-board beers.

"Vodka," she said to McKenzie, trusting him with a sizeable draft on her account.

"Walford's is cheap, Green dock, listen, I got some incidentals I need, stand you three bottles if you hit supply for me."

"Hell," McKenzie said, "give us a list. Nobody's in port but us, we got to make do with dockers, and you know Figi's going to be in a damn card game from the time he hits—Park and me can go shopping, buy you anything you want."

"You're a love," she said, feeling better for the moment, and took McKenzie off in the corner and exchanged about twenty concentrated minutes of accumulated favor-points.

Real special, this time, rushed as it was—hard to know what it was, maybe that they were both in a desperate hurry, and taking time to be mutually polite, maybe just that they'd gotten beyond acquainted and all the way over to looking out for each other.

She wanted that right now, wanted somebody it just wasn't complicated with, who cared about her; and she hurt her back doing it and didn't regret it later, when the takehold was sounding and she hauled thirty kilos of hammock and duffle down to the stowage area to clip in and hang on with the rest of alterday and most of mainday.

Not the mofs. Mofs and a few of the mainday tekkies got to ride the lift down from the bridge to the airlock, of course—except for the lucky few who drew duty part or all of the port-call.

I hope to hell Fitch gets a long liberty. Hope the sonuvabitch gets laid at least once.

Might help his disposition.

Mostly she worried about Hughes and his friends being out there with Musa and her and NG not being. "Keep an eye on him," she'd asked McKenzie, and McKenzie'd sworn he would.

They made a tolerably soft dock, no teeth cracked, no bruises, and crew stood in harness waiting for permission to move about, laying grandiose plans for the bars they were going to hit– yeah, sure, mates, on Thulec

They got the permission, they undipped, they milled or they settled down on their duffles and checked through their cred-slips.

Johnny Walters had left his kit. There was usually some poor sod. There was always a volunteer who'd get it down by shift-change. "Yeah," Bet said. "NG or I, one. Who else,?

Make a list."

Damn list always grew when people found out there was a quarters-run going. "Shit.

Write it down! I got a year's worth of favor-points coming from you guysc"

Except Dussad, out of mainday Cargo, who muttered something about having NG into his stuff—

"You want a favor?" Bet asked, swinging around, read the name on the pocket and said, "Dussad? You want a favor or you got a problem with me and my mate?"

"You got lousy taste," Dussad said, and of all people, Liu said, "Take it easy." And McKenzie said, "Nothing wrong with NG. He just doesn't talk too good."

"Ask Cassel," a mainday woman said.

God, they couldn't move, they were here till they got orders. NG just stood there, nobody could go anywhere or do anything.

Gypsy said, "Man's got by that. Man's stood his watches, took his shit for it, long enough."

And Musa:

"Damn valve blew, Ann, you get your head in the way of it and it happens, it don't matter if you got a mate there. The rest of it's hell and away too old to track."

"He got an opinion?"

"Let him the hell alone," Bet said, and threw NG a look, couldn't not; NG was just staring somewhere else, jaw clenched—God, he couldn't talk, just damn couldn't, out-there for the moment. "Let him alone."

"I know what his mates are saying. I want to hear what he's got to say about it, all right? There's a lot of trouble going on. I want to know what the guy has to say."

McKenzie said, "I'll buy you a drink, Dussad. We'll talk about it."

Quiet for a second or two, real tense. The lift clanked and whined, high up on the rim—mofs doing their business with dockside.

"Drop it," Liu said. "Drop it, Dussad. Later. All right?"

"What about my kit?" Walters asked, in the silence after. "Is somebody going to go after it?"

They finished the fetch-downs list, mofs went out and did customs, lot of noise from the lift and the airlock; and they waited and talked, and bitched—

Prime bitch coming, if you drew duty, if you had to get up and wish everybody Drink one for me, while the captain got on the general com and told everybody clear out and when the board-call was. "I got a couple of old friends here," Bet said to Musa. "Drop in by the Registry, wish Nan Jodree and Dan Ely g'day for me. Stand 'em a drink if they got the time."

Depressing, when everybody cleared out in a noisy rush and left the downside corridor all to the two of them—and NG paying attention again, but down-faced, quiet.

Damn that Dussad.

"Well?" she said, looking at NG, and sighed and picked up the duffle and the hammock. "Where d'we put it?"

NG looked at the corridor and looked up and down the curves in either direction, and finally sighed and said, in all that awful quiet of shutdown: "Locker's all right."

They got Walters' kit down, a matter of climbing up the curve using the safety clips, also stuff for Bala and Gausen and Cierra—and for Dussad, NG did that, did all the climbing around, the dangerous part, where you could take a long, long fall if you got careless clambering through the quarters. "You'll hurt your back," he told her. "I'll do the climbing, you just stay down here and catch it."

He acted all right. She wished she knew what to say about Dussad and mainday shift, that had been NG's—and Cassel's. She wished she knew what was going on in his head and she wished she had Musa here, to talk to NG, if nothing else. Or Bernstein. Bernie could get through to him. She wasn't sure she could, she wasn't sure she wanted to get into the topic with him at all.

DamnDussad. Hughes had stayed out of it, Hughes had to be taking all of it in and wanting to say something—and there was no doubt he would be saying something, in the bars and up and down dockside for five days, causing as much damage as he could, dropping stuff in ears he knew would be receptive, and in a liberty, down to the last day, the shifts mixed.

Damn, she wanted to be out there. Most of all she wanted NG out there in Musa's keeping, not on-ship, brooding on things, working alone while his partner was off doing what she couldn't let him know—

She ought to tell NG, hadto tell him sooner or later what was going on, and alone on the alterday watch might have been a decent time to do it, except for Dussad and that damn woman from mainday—Thomas, she thought it was, Ann Thomas, navcomp, Hughes'opposite. Alterday andmainday nav both were a pain in the ass, she decided—

must be something in the mindset; while Dussad, out of Cargo, was a hard-nosed hard-sell sonuvabitch, but you couldn't fault him too much—just want to bust his damn thick skull, was all. "Eyes up!" NG yelled from overhead. "Fragiles!"

They weren't the only crew missing liberty: Parker and Merrill were on mainday duty in Engineering, and Dussad and Hassan just had a partial, going out to the suppliers' and dealing for the ship, with whatever spare time they were efficient enough to gain; while Wayland and Williams were on a three-day pass, having to come back and supervise the supply loading, and a lucky handful of bridge crew, rotating off-ship for sleep and whatever rec-time they could squeeze in, was responsible for the fill, indicator-watching, mostly, and communication with Thule Central—an ops routine she knew, for once, the intricacies of cables and hoses, the names of the lines and what the hazards were—

learned it because you'd always had to worry about sabotage, in the war, and when Africawas in dock, the squad was always out there in full kit, checking the hook-ups, posting guard—

Dammit.

She kept remembering. She didn't want to. There were those dead rigs topside, waiting for her, like ghosts—

And NG was going to ask questions, NG had a natural right to ask questions about where she was going every day, and why.

They had the night, at least. "I'm not making love in any hammock," she said to NG, setting up, having consulted Parker and Merrill via com on what was going to be quarters for four people, alternately, in the main stowage—so they just spread their two hammocks down for padding on the stowage deck, and, it turned out during the set-up, got themselves a brand-new bottle of vodka when Walters and some of the guys showed up to pay off the fetch-downs.

"You sure ain't missing much," Walters delayed to say to them. "Place is dead, places are closed up, about two bars and a skuzzy sleepover still open, and that's it. Nothing alive out there but echoesc"

Made her feel sad, for some odd reason, maybe just that it was a slice out of her life, however miserable, maybe that there was something spooky about it now, knowing a piece of humankind was dying, the dark was coming just like they'd said, taking the first bases humans had made leaving Sol System.

Like those names in the restroom they just painted over. Polaris, and Golden Hind.

God, Musa could probably remember Thule in its heyday.

And came back, a crewman on an FTL, to see it die.

"Bet?" NG asked her, nudged her arm, when the lock-door had shut, when Johnny Walters was away to the docks, and she thought, for no reason, Everything we ever did—

the War, and all, they'll paint right over, like it never was, like none of us ever died—

Mazian doesn't see it. Still fighting the war—

Hell. What'swinning? What'swinning, when everything's changing so fast nobody can predict what's going to be worth anything?

She felt NG's hand on her shoulder. She kept seeing Thule docks, Ritterman's apartment, the Registry—

The nuclear heat of Thule's dim star.

Curfew rang.

Walters' vodka, bed, privacy, all the beer they could reasonably drink and all the frozen sandwiches they could reasonably eat, out of Services, next door.

Wasn't too bad, she decided, putting tomorrow out of her mind, the way she had learned to do. Just take the night, get her and NG fuzzed real good—

Tell him later. The man deserved a little time without grief.

So they ate the sandwiches with a beer, chased them with vodka, made love.

Didn't need the pictures. Didn't need anything. NG was civilized, terribly careful of her back—

Not worth worrying about, she said. And got rowdy and showed him a trick they used to do down in the 'decks, her and Bieji.

"God," he said. He ran his hand over the back of her neck.

Nobody else had that touch. Nobody else ever made her shiver like that. Nobody else, ever.

Hewas the one who got claustrophobicc but for a second she couldn't breathe.

Here and now, Yeager. This ship.

This man. This partner.

"You all right?" he asked.

"Fine," she said, and caught the breath, heavy sigh. "I just can't get stuff out of my mind."

He worked on that problem. Did tolerably good at it after a minute or two, till she was doing real deep breathing and thinking real near-term.—One thing with NG, he didn't question much, and he knew the willies on a first-name basis. Knew what could cure them for a while, too.

She said, somewhere after, when she found the courage: "Bernstein just left me this nasty little list of stuff, topside, seems I'm the mechanic and you got the boards." She tried to say what it was. And had another attack of pure, despicable cowardice. Couldn't trust it. Couldn't predict what he'd do. Didn't want a blow-up til she'd gotten a day or so alone with him, softened him up, got an idea what was going on with him. "I hate it like hell. You're going to be alone down there."

"Been alone before," he said. "Been alone on port-calls for years."

He didn't ask what the work was. She told herself that if he had asked she would have gone ahead and spilled it right then. But he didn't. Wasn't even curious.

Thank God.

CHAPTER 24

MS. YEAGER," Wolfe said, when she arrived on the bridge and looked around for the mof-in-charge. The captain was not who she was looking to find.

"Sir," she said, and by way of explanation: "Mr. Orsini—"

Wolfe nodded. "Go to it, Ms. Yeager."

"Thank you, sir." She gave a bob of the head and took herself and her tool-kit to the number one topside stowage, where she could draw an easier breath.

It wasn't Fitch in charge, thank God, thank God.

Not Fitch in charge anywhere else on the ship, she hoped, but there was no way to find that out without asking, and she didn't figure asking was real politic. Mofs were handling the matter, mofs had their ways of saving face, and if Fitch wason board he was going to be twice touchy if they had him under any hands-off orders regarding her.

Couldn't push it. Didn't even dare worry about it.

So she got down to work, clambered up the inset rungs to set a 200 kilo expansion track between two locker uprights, hooked a pulley in, ran a cable and a couple of hooks into the service rings of the better of the two rigs, and hauled the thing up where she could work without fighting it.

You could figure how Walid might have died—considering there was no conspicuous damage to the rig, no penetration at first glance that ought to have killed him—but those that got blown out into space had been low-priority on rescue. Nobody in authority on Pell had much cared about the survival of any trooper, and the air only held you for six hours.

Six hours—floating in the dark of space or the hellish light of Pell's star.

Arms wouldn't work far enough to reach the toggles. Couldn't even suicide. The rig had caught some kind of an impact—when it was blown out Pell's gaping wounds into vacuum, maybe; it had survived the impact, but it was shock enough to throw play into every joint it owned—

–and spring a circulation seal in the right wrist and a pressure seal in the same shoulder. Scratch the six hours. You could lose a wrist seal and live without a hand, but when you lost a main body seal, you just hoped you froze fast instead of boiled slow—

and which happened then depended on how much of you was exposed to a nearby sun.

"Helluva way, Walid." With a pat on the vacant shell. "You should've ducked."

Lousy sensahumor, Bet—

Walid's voice. Clank of pulleys, skuts bitching up and down the aisles while they suited up, the smell of that godawful stuff they sprayed the insides withc

A whiff of it came when she took a look at the seals. Even after a guy died in the damn thing, even after the rig had been standing months and years in a chilled-down storage locker, the inside still smelled like lavatory soap.

She took inventory on the Europerig, real simple c.o.d., a lousy big puncture in the gut, right under the groin-seal. Big guy, name of W. Graham, Europe's, tac-squad B-team—Willie, she remembered, strong as any two guys, but no chance at all against a squeeze or an impact powerful enough to punch right through quadplex Flexyne.

God.

So, well, if you wanted to see how bad the joints were, the easiest way was just to strip down and start building the rig around you joint by joint, freezing not only your ass off, but various other sensitive spots, because the internal heater wouldn't work until the rig was powered up, and you didn't want the power on while you were making tension adjustments. You messed around with lousy little pin-sized wrenches and screwdrivers and tried not to chatter your teeth loose while you were getting the wrench or the screwdriver seated in little inconspicuous holes, about three to five of them a joint, and you fussed and you messed with one turn against another, and you tried the tension in this and that joint, till it felt right.

While your nose ran.

But you warmed up, joint by joint. Joint by joint, starting with the boots, the rig cased you in and linked up, joint with joint and contact with contact, heavy as sin and about all you could do to lift a knee and test the flex, clear up to the body-armor.

Tension-straps between two layers of the ceramic, each with their little access caps, and their nasty little adjustment screws on the action, too, four or five a segment, that pulled the sensor contacts up against bare skin, contacts that were going to carry signals to the hydraulics—all those had to be tightened or loosened, so they'd all loosen up to the right degree when you pulled the release to get out of the armor, and go right back to the proper configuration when you got inside and threw the master switch: you could feel all those little contact-points, and they shouldn't press hard, but they shouldn't lose contact either, and the padding that kept you from bumping up against those contacts too hard in spots had to be tightened down or loosened up with another lot of fussy little spring-screws.

Some damned fool had just got in and powered up. Probably fallen on his ass or sprained something just trying to stand up.

She hoped to hell it had been Fitch.

Maybe it was that thought that brought him.

The door opened. And she was sitting there on the deck half-naked and half-suited, with Fitch standing in a warm draft from the door.

Fitch looked at her, she looked at Fitch with her heart pounding. Dammit. The man still panicked her.

"Yessir," she said. "Excuse me if I don't get up, got no power at the moment."

"How's it going?" Fitch asked.

Plain question. She rested an armor-heavy wrist on an armored knee. "Thing's a mess," she said. "Fixable. Take me a little while. Few days on this one."

Silence, then. "Tac-squad, huh?"

"Yessir."

If you had a quarrel with a mof, you for God's sake didn't act up and you didn't get snide, you just kept your face innocent and your voice calm and all professional, no matter what you were thinking.

"Is that insubordination, Ms. Yeager?"

"Nossir."

"Hard feelings, Ms. Yeager?"

"I've had worse than you give, sir."

Fitch took that and seemed to think about it a minute.

Stupid, Yeager, real stupid, watchthat mouth of yours.

"Smartass again, Yeager?"

"Nossir, no intention of being."

"Are you quite sure of that, Ms. Yeager?"

"Twenty years on Africa, sir, I was never insubordinate."

"That's good, Ms. Yeager. That's real good."

After which, Fitch walked out and shut the door.

Dammit, Yeager, that was bright.

God, NG's working alone down there. Where's Wolfe?

Who else is on watch?

She threw the four manual latches on the gauntlet, slid it off; threw latches on the body-armor and on the chisses and boots. Fast. And scrambled up and put clip-lines on the scattered pieces and grabbed her clothes.

"Got to check supply," was the excuse she handed the bridge when she went through.

"Be back soon as I can."

Down the lift, all the way to downside, and up the curving downside deck in as much hurry as she could, past the deserted lowerdeck ops, up-rim toward the shop.

And naturally she popped into Engineering on the way. "H'lo," she called out at NG's back, over the noise of working pumps, and startled NG out of his next dozen heartbeats.

"God," he said.

"Fitch," she said. "Just thought I'd warn you."

He leaned back against the counter. She stepped up onto the first of the gimbaled sections that turned Engineering into a stairstep puzzle-board. "No particular trouble," she said, and raised a thumb toward the topside, casual. "Captain's up there too, what I saw."

"They come and they go," NG said. Worried, she thought. "Captain may have gone dockside. Don't get off in places with no witnesses."

"I'm working right next the—"

The lift was operating, audible over the heartbeat-thump of the fueling pumps.

"—bridge. I better get to the shop. I'm picking up some stuff, if Fitch asks."

"He'll ask," NG said, sober-faced, and she started back to the corridor and stopped again, with this terrible fear that Fitch intended something, that Fitch could, for firsts, spill everything.