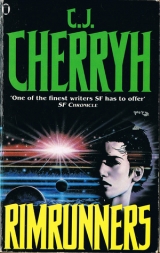

Текст книги "Rimrunners "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

"Rimrunners"by C.J.Cherryh

THE POST-WAR PERIOD

From: The Company Warsby Judith Nye

2534: University of Cyteen Press, Novgorod, U.T.

Bureau of Information ref. # 9795 89 8759

In 2353, when the Earth Company Fleet fled Pell under the command of Conrad Mazian, the overriding fear of both Union and Alliance was that Mazian would retreat to Earth and draw on its vast material and human resources. So the immediate strategic consideration was to deny the Fleet that refuge.

It was rapidly clear that the Sol Station megacorporations which had built the Fleet did not support Mazian in his bringing the War to Sol system; and the arrival of Union warships before the Mazianni could so much as effect repairs drove Mazian into a second retreat.

Alliance ships, dropping into Sol system close behind the Union fleet, entered into immediate negotiations to enlist Earth in the Alliance. Union ships, returning from the battle, offered similar terms. The governments of Earth saw in this rivalry a situation which did not demand their capitulation to either side; and in effect, while it may have been Earth's fragmented politics that led to the Company Wars in the first place, it was that long Terran experience in diplomacy which enabled a reasonable peace and assured the survival of the Alliance.

In fact it can be argued that without Earth's independence, the Alliance could not have maintained itself as a political entity, and without the Alliance, Earth could never have remained independent. Alliance, consisting at the time only of one star-system, Pell, immediately laid claim to the abandoned Hinder Stars– a bridge of close-lying points of mass which, linking Pell to Earth, promised economic growth for the newborn Alliance.

Union, which had come through the war with its industry intact, laid claim to the war-ravaged nearer star-stations of Mariner and Pan-paris, simply because it was the only government capable of the huge cost of rebuilding. Further, it offered repatriation, free transportation and a full station-share to certain refugees from those stations who had been evacuated to Pell– specifically to refugees who could demonstrate technical skill and who had no record of the kind of criminal profiteering that had arisen in Pell's quarantine zone. This program of repatriation, the work of Union Chairman Bogdanovitch and Defense Councillor Azov, drew a large number of skilled and educated refugees back into Union and, according to some speculations, purposely left the Alliance a troublesome remnant of those whom Union considered undesirables.

Nor was Pell Station able to absorb such a number of unskilled and destitute.

The Alliance solution was to offer similar station-shares and free transport to the seven mothballed stations it had claimed in the Hinder stars.

Meanwhile the allies had hoped that the Company Fleet had exhausted itself with no possibility of return from deep space; but Mazian's escape from Sol had evidently been toward some secret supply dump, at precisely what point of mass still remains a mystery.

The Mazianni made a sudden return to Sol, but, thanks to the allied forces who had remained on guard there, they were driven a second time into deep space.

After this skirmish Union strategy was to deprive the Mazianni of supply by driving them into deep space on the far side of Sol. Union viewed the re-opening of the Hinder Stars and the resumption of trade with Earth as extending a potential supply line to Mazian, who had regularly provisioned his ships by raiding commercial shipping throughout the latter stages of the War; but the newborn Alliance, with only the Hinder Stars and its proximity to Earth as assets, determined to take the risk over Union's protests.

It was a strangely assorted group of volunteers who went out to re-open those abandoned stations, some adventurers, some survivors of the riot-wracked quarantine zone at Pell, and some few certainly with dreams of a new Great Circle tradec

Alliance offered inducements to small, marginal freighters to take those dangerous routes, an opportunity which promised survival for such ships in a burgeoning post-war trade; but it reckoned without the discovery of a point of mass off Bryant's Star that bypassed four of the newly reopened stations, and most of all it reckoned without the competition of Union-built super-freighters likeDublin Again which soon moved in off Union's long-jump routes– ships which could, via tiny Gaia Point, hitherto unreachable by any freighter, bypass the Hinder Stars altogetherc

CHAPTER 1

EVERY DAY she came into the Registry, and he began to watch her—tall, thin woman, unremarkable among others who came looking for jobs, men and women beached at Thule, men and women at the end of the line and hoping for a new beginning somewhere, on some further station or aboard some ship that came to dock and trade in the days of Thule's second fading.

The jumpsuit had grown threadbare, once a definite blue, no longer crisp lately, but still clean. Her fair hair was haggled up the back and sides, a ragged mop of straight hair on top, crackling with fresh-washed static. Each day she walked into the Registry and signed the application sheet: Elizabeth Yeager, spacer, machinist, temp;and sat down, hands folded, at a table at the back.. Mostly she sat alone, turned talk away, stared right through any hardy soul who tried her company. At 1700 each mainday the Registry closed and she would go away until the next sign-in, at mainday 0800.

Day after day. She went out to interviews and sometimes she took a temp job and dropped out for a day or two, but she always came back again, regular as Thule's course around its dim, trade-barren star, and she took her seat and she waited, with no expression on her face. The rest of the clients came and went, to jobs, to working berths or paid-passage on the rare ships that called here. But not Elizabeth Yeager.

So the jumpsuit—it looked like the same one day after day—lost its brightness, hung loose on her body; and she walked more slowly than she had, still straight, but lately with a feebleness in her step. She took the same seat at the same table, sat as she had always sat, and these last few days Don Ely had begun to look at her, and truly to add up how long she had been coming here, between her spates of temp and fill-in employment.

He watched her leave one mainday evening; he watched her come in and sign the next morning, one of forty-seven other applicants. It was week-end, there was nothing in dock, little trade on the dockside, nothing in Thule's dying economy this week to offer even a temporary employment. There was a perpetual sense of despair all around Thule in these last months, of diminishing hopes, an approaching long night, longer than her first, when the advent of FTL technology had shut her down once: there was talk now of another imminent shut-down, maybe putting Thule Station into a trajectory sunward, to vaporize even her metal, because it was uneconomical to push it on for salvage, and because the most that anybody hoped for Thule now was that she would not suffer a third rebirth as a Mazianni base.

Nothing in port, no jobs on station except the ones station would allot for minimum maintenance.

And he watched the woman go to her accustomed table, her accustomed seat, with a view of the news monitor, the clock, and the counter.

He went to the vacant workstation behind the counter, sat down and keyed up the record: Yeager, Elizabeth A., Machinist, freighter. 20 yrs.

More?comp asked. He keyed for it.

Born to a hired-spacer on the freighter Candide, citizenship Alliance, age 37, education level 10, no relatives, previous employment: various ships, insystemer maintenance, Pell.

He recalled other applicants in the same category, as the records of hires floated across his desk. They were either employed at Thule on the insystemers—keeping Thule's few skimmers running took constant maintenance—and stacking up respectable credit; or they had shipped out to Pell or on to Venture. But Yeager got sweep-up jobs, subbed in for this and that unskilled labor when somebody got sick. Waiting all this time, evidently, for something to turn up. And nothing did, lately.

He watched her sit there till afternoon, when the Registry closed, watched her get up and walk to the door, wandering in her balance. Drunk, he would have thought, if he did not know that she had hardly stirred from that chair all day. It was that kind of stiff-backed stagger. On drugs, maybe. But he had never noticed her look spaced before.

He leaned on the counter. "Yeager," he said.

She stopped in the doorway and turned. Her face, against the general dim lighting of the docks outside, was haggard, tired, older than the thirty-seven the record showed.

"Yeager, I want to talk to you."

She came walking back, less stagger, but with that kind of nowhere look that said she was expecting nothing but trouble. Close up, across the counter, she had scars—two, star-shaped, above her left eye; a long one on the right side, one on the chin. And eyes—

He'd had a notion of a woman in trouble; and found the trouble on his own side, having gotten this close. Eyes like bruises. Eyes without any trust or hope in them. "I want to talk with you," he said. She looked him over twice and nodded listlessly; and he led her back into the inner, glass-walled hall, toward his office. He put the lights back on.

She might think about her safety. He certainly thought about his, the danger to his career, such as it was, bringing her back here after hours. He punched the com on his desk, waved Yeager to a chair as he sat down behind its defending breadth, hoping the other Registrar had not gotten out the front door yet. "Nan, Nan, you still out there?"

"Yes."

That was a relief. "I need two cups of coca, Nan, heavy on the sugar. Favor-points for this. You mind?"

A delay. "In both?"

He always drank his unsweetened. "Just bring it. Got any wafers, Nan?"

Another pause. A dry, put-upon: "I'll look."

"Thanks." He leaned back in his chair, looked at Yeager's grim face. "Where are you from?"

"This about a job?"

Hoarse. She smelled strongly of soap, of restroom disinfectant soap, a scent he had to think awhile to place. Under the overhead lighting her cheeks showed hollow and sweat glistened unhealthily on her upper lip.

"What was your last berth?" he asked.

"Machinist. On the freighter Ernestine."

"Why'd you leave her?"

"I worked my passage. Hard times. They couldn't keep me."

"They dumped you?" At Thule, that was a damned rough thing for a ship's crew to do to a hire-on, or she had deserved it by things she had done, one or the other.

She shrugged. "Economics, I guess."

"What are you looking for?"

"Freighter if I can get it. Insystemer's all right."

A little hope enlivened her face. It made him guilty, being in the least responsible for that illusion. "You've been here a long time," he said, and said, to be blunt and quick, "I haven't got anything. But there's station work. You know you can go station-work. Get basics that way, shelter, food, get an automatic no-debt ticket out of here if there's a fold-up. It's pretty empty here. Food's awful but the accommodations are take-your-pick all over station. A machinist—could damn sure get more than that, if she was good."

She shook her head.

"Reason?"

"Spacer," she said.

He never quite understood that. He had heard it a hundred times before—the ones who had rather starve than go station-side, take a job, draw the ration: the ones who would go by drugs or outright suicide, rather than lose their priority on the Registry hire-list, that little edge that meant who went to the interviews first.

"Papers?" he asked, because there had been none on the record, comp-glitch, he reckoned, nothing unusual in Thule's frequently screwed-up systems.

She touched her pocket, not offering to show them.

"Let's see," he said.

She took them out then, offered them in a hand that shook like an old woman's.

"My name's Don Ely," he said conversationally, since it occurred to him he had not.

He looked at the folder—not the official paper it ought to have been, just a letter.

To any captain, it said.

This is to attest the good character and work record of Bet Yeager, who shipped with us from '55 to 56 and who paid passage with honest work at watch and guard, at galley and small mechanics, general maintenance, in which she has many skills which she has gained under supervision of able spacers and which she performed with zeal and care. She leaves this ship with the regret of me personally and all crew.

She earned her passage and had credit in the comp at her leaving.

Bet Yeager boarded without papers under emergency conditions and this ship testifies that they know her to be the person Elizabeth Yeager whose thumbprint and likeness are hereto affixed, who served honorably on this ship, and hereby, by my authority, this stands in lieu of lost identification and swears her to be this person Elizabeth Yeager according to the Pell Convention, article 10.

Signed and Sworn to by: T. M. Kato, senior captain, AM Ernestine, lately based at Pell.

E. Kato, a/d captain.

Q. Jennet Kato, chief engineer, IS pilot.

Y. Kato, purser.

G. B. Kato, supercargo, IS pilot.

R. Kato; W. Kato; E. M. Tabriz;

K. Katoc

He looked at the back. The signatures went on. The paper was wearing through at the folds. There was no other sheet in the papers-folder, nothing official but Ernestine'sembossed seal and the date.

"That's it?" he asked.

"War," she said, flat and quick,

"Refugee?"

"Yes, sir."

"Where from?"

" Ernestine," she said. "Sir."

Cold turn-down. Go to hell. Sir.

He saw Nan behind the glass wall, coming down the hall with the tray. She caught his eye discreetly, got his nod and came inside with it.

Yeager took the cup Nan offered. Her hand shook. She ignored the wafers and set the cup down untasted on the table beside her.

"Set it there," Ely told Nan, meaning the tray with the wafers, indicating the same table. He took his own cup and sipped at the sweet stuff as Nan set the rest by Yeager.

"Have a wafer," he said to Yeager.

Yeager took one, picked up the cup and sipped at it.

Hell with you, that look still said. I'll take hospitality, you better not think this is charity.

"Thanks," he said to Nan. "Hang around, will you?"

Nan gave him a look, added zero up, and left in irritated, worried patience. Nan had her own problems, probably had dinner going cold in the oven if this dragged on, maybe had a date to keep. He owed her for this one: and Nan clearly thought he was a fool. Nan, being a veteran of the Registry at Pell, had probably seen hundreds of Yeagers while he had sat in insulated splendor in Mariner's shipping offices. Certainly they dealt with odd types in this office. All of them had troubles. Some of them weretrouble.

He laid Yeager's paper on the desk in front of him. Her eyes followed that, the first hint of nervousness, now that Nan was gone, up again, to meet his. "How long," he asked,

"have you been here?"

"Year. About."

"How many jobs?"

"I don't know. Maybe two, three."

"Lately?"

A shake of the head.

"Maybe I could find something for you."

"What?" she asked, instant suspicion.

"Look," he said, "Yeager, this is straight. I've seen you around—a long time. This—"

He flicked a finger at the paper from Ernestine. "This says you know how to work. You show that to the people on interviews?"

A nod of her head. Expressionless.

"But you won't take station work."

A shake of the head.

"Those papers don't say anything about a license. Or a rating."

"War," she said. "Lost everything."

"What ship?"

"Freighters."

"Where?"

"Mariner. Pan-paris."

"Name." Mariner was his native territory. Home. He knew the names there.

"I worked on a lot of them. The Fleet came through there, blew us to hell. I was stationside." No passion in the voice, just a recital, hoarse and distant, that jarred his nerves. It was too vivid for a moment, too much memory, the refugee ships, the stink and the dying.

"What ship'd you transport on?"

"Sita."

That was a right name.

"No records, no registry papers." She set the cup down, hardly tasted, pocketed the wafer. "They got stolen. So'd everything else. Thanks all the same."

"Wait," he said as she was getting up. "Sit down. Listen to me, Yeager."

She stood there staring down at him. A light sweat glistened on her face, against the dark outside, the lone desk light in the next glass-walled cubicle that was Nan's backroom office.

"I was there," he said. "I was on Pearl. I know what you're talking about. I was in Q, just the same as you. Where are you living? On what? What pay?"

"I get along. Sir."

He took a breath, picked up the paper, offered it back, and she took it in a shaking hand. "So it's none of my business. So you don't take handouts. I watch you day after day coming here. It's a long wait, Yeager."

"Long wait," she said. "But I don't take any station job."

"And you'd rather starve. Have people offeredyou other jobs?"

"No, sir."

"You turn them down?"

"No, sir."

It would have been in the record. Illegal to turn them down, if she was indigent.

"So you fail the interviews. All of them. Why?"

"I don't know, sir. Not what they're looking for, I guess."

"I tell you what, Yeager, you do the scut around this office for a few weeks, you keep the place swept and the secs happy. A cred a day worth it?"

"I stay on the Registry."

"You stay on the Registry."

She stood there a moment. Then nodded. "Cash," she said.

It had to be. He nodded. She said all right, and she was his liability, a problem not easy to cure; and his wife was going to look at him and ask him what the hell he was doing handing out seven cred a week to a stranger. A Registry post on Thule was no luxury berth, and if Blue Section questioned it he had no answer. Probably it broke regulations. He could think of three or four.

Like unauthorized hire-ons in a station office.

Like failing to notify security of a probable free-consumer. No way in hell that Bet Yeager afforded a sleepover room. Damned right she was an illegal, taking Station supplies and returning nothing.

Day after day in the Registry. With the smell of restroom soap.

He fished in his pocket. What came out was a twenty-chit. He found no smaller change. He offered it, regretfully.

"No, sir," Yeager said. "Can't say where I'll be twenty days from now. Ship's due."

"So pay me back if you get a berth. You'll have it then."

"Don't like debts. Sir."

"Won't fill the gut, Yeager. You don't eat, you can't work."

"No, sir. But I'll manage. Your leave, sir."

"Don't be—"– a damn fool, was in his mouth. But she was like as not to walk out then. He said: "I want you here in the morning. With a full stomach. Take it. Please."

"No, sir." The lip trembled. She didn't even look at the money he was holding out.

"No charity." She touched the pocket, where the papers were. "Got what I need. Thanks.

See you tomorrow."

"Tomorrow," he said.

She gave a scant nod, turned and left.

Military, he thought, putting it together. And then he was worried, because there was nothing like that in the letter, very few freighters were that spit-and-polish, and military meant station militia, or it might just as easily mean Fleet or Union, if it was more than a few years back.

That scared him—because big, armed merchanters were rare, because Norway, the only real force the Alliance had, was God-knew-where at any given time: the Earth Company Fleet was God-knew-where too, and every unidentified blip that showed up on station longscan sent cold chills through Thule.

Call security, was the impulse that went through Ely's bones. An investigation was not an arrest. They could do a background check, ask around, see if there was anyone else of the three thousand souls on Thule who remembered Bet Yeager on Sitaor in Pell's infamous Q-zone.

But Security wouldarrest the woman if she came at them with that none-of-your-business attitude, Thule's very nervous Security would certainly haul her in and question herc feedher, that much was truec but they would go on to ask unanswerable questions like Where are you living? and How are you living? And maybe Bet Yeager was everything she said, and had never committed any crime in her life but to starve on Thule docks, but if they got the wrong answers to those questions about finances, they would put Bet Yeager on station rolls and charge her with her debt, and Bet Yeager would end up a felon.

A spacer—would end up shut up in a little cell in White Section. A spacer—who would suffer anything to keep to dockside and the chance of ships—would end up working for a fading station till they turned the lights out.

That was what his inquiry could do to Bet Yeager.

He walked out into the front office, behind the counter, saw Yeager open the outside door.

He had no idea where Yeager might go for main-night; tucked up in some cold corner of dockside, he guessed, wherever she had been spending her nights. Wait, he could say, right now. He could take her home, feed her supper, let her sleep in the front room. But he thought of his wife, he thought of their own safety, and the chance Bet Yeager was more than a little crazy.

The word never left his mouth, and Yeager went out the door, out into the actinic glare and deep shadow of dockside.

"Huh," he said, recalled to the office, to Nan standing by her desk looking at him.

He motioned toward the door. "You know that one?"

"Here every day," Nan said.

"Know anything about her?"

Nan shook her head. They shut down the last lights, walked to the door themselves.

The door sealed and they walked down the docks together, under the cold, merciless glare of the floods high in the overhead, in the chill and the smells of cold machinery and stale liquor.

"I offered her a five once," Nan said. "She wouldn't take it. You think she's all right in the head? Think we—maybe—ought to notify security? That woman's in trouble."

"Is it crazy to want out of here?"

"Crazy to keep trying," Nan said. "She can sit still. Another year, they'll shut us down, pack us up, move us on to somewhere. She could get a berth from there, likely as here.

Maybe more likely than here."

"She won't live that long," Ely said. "But you can't tell her that."

"I don't like her around," Nan said.

He wished he could do something. He wished he knew if they ought to contact security.

But the woman had done nothing but go hungry. He had worked a year in the Registry System, helped administer the hiring system that was supposed to be humane, that was supposed to give highest priority and first interviews to the longest-listed. But it ended up encouraging cases like Bet Yeager, it ended up making people hang on, suffer anything rather than step out of line and let somebody get in ahead of them, God knew where another spacer was going to come from now who could threaten Yeager's seniority on the roll, if it was not the incoming Mary Goldthat let him off—but tell that to Yeager, who was down now to scrabbling for the little temp jobs that made the difference in how long she could hold on, and thosehad become nonexistent. Another few days and it was the station bare-subsistence roll: the station judiciary always reckoned free-consumers at ten cred for every day they could not prove they had been solvent. In Bet Yeager's case, that money had probably run out a year ago. And she had tried so damned long.

Next week, she said. Maybe next week. A ship was due in.

But none of the other ships had taken her.

CHAPTER 2

BET WALKED carefully, having refuge in sight, the women's restroom on Green dock, a closet of a facility, an afterthought the way the whole dock was an afterthought, the bars and the sleepovers, the cheap restaurants, in a station designed for the old sublights and now trying, in a second youth, to serve the FTLs and their entirely different needs.

And there was this restroom. It was graffitied and it stank and there was one dim light in the foyer and one no better in the restroom, with four stalls and two sinks, where spacers in the early-heyday of the place had engraved shipnames and salutations for ships to come:

Meg Gomez of Polaris, one said. Hello, Golden Hind.

Legendary ships. Ships from the days when stations were lucky to get a shipcall every two years or so. Something like that, station maintenance had painted over.

Damn fools.

It was home, this little hole, a safe place. She found the dingy restroom deserted as it usually was, washed her face and drank from the cold trickle the better of the two sinks afforded—

Her legs failed her. She caught herself against the sink, stumbled and sank down against the wall beside it. For a moment she thought she was going to pass out, and the room swam crazily for a while.

Not used to food, no. She'd wanted the coca for the sugar in it, but the little that she had drunk had almost come back up right in Ely's office and now the half a wafer threatened to, while her eyes watered and she fought, with even breathing and repeated swallows, to keep from the heaves.

Eventually she could take a broken bit of wafer from her pocket and nibble on it, not because it tasted good, nothing did, now, and eating scared her, because the last had made her sick and she couldn't afford to lose the little food that was in her stomach. But she tried, crumb at a time, she let it dissolve on her tongue and she swallowed it despite the cloying sweetness.

Smart. Real smart, Bet.

Got yourself into a good mess this time.

Time was on Pell she'd hid like this. Time was on Pell she'd been almost this desperate. Hard to remember one day from the other when it got that bad. Somehow you lived, that was all.

Somehow you stuck it out, in this dingy place, sitting on an icy floor in the loo trying to keep your gut together. But bite at a time, you kept it down and it kept you alive, even when you got down to a pocket full of wafers and the hope of a cred-a-day job. A cred got a cheese sandwich. A cred got a fishcake and a cup of synth orange. You could live on that and you had to survive this night to get it, that was all.

She'd stopped believing yesterday, had really stopped believing. She'd gone in to the Registry today only because maintenance checked out the holes now and again, because going to the Registry was a way to stay warm, and showing up there proved she was still looking, the one proof an un-carded resident could use to maintain legal status. And most of all it kept her priority with any available job on that incoming freighter. Hoping for that was an all-right way to die, doing what she chose to do, looking forward to what she insisted was the only thing worth having. A good way to die. She'd seen the bad ones.

And if it got too bad there was a way to check out; and if the law caught her there were ways to keep from going to hospital. She carried one in her pocket. She'd gotten down to thinking about when, but she hadn't gotten to that yet, except to know if she passed out and people were calling the meds she might; or if they convicted her and slapped a station-debt on her—she could always do it then. Just check right out, screw the lawyers.

And now there was a little more chance. So she'd been right about sticking it out so far. She could turn out to be right in everything she'd done so far. She could win. That ship next week could come in short-handed. It could still happen.

So she sat there in the shadow of the sink awhile till one whole wafer had hit bottom, and then she knew she had to move because her legs and her backside were going numb, so she pulled herself up by the sink and got some more of the metal-tasting water on her stomach and went into one of the stalls to sit down, arms on knees and head on arms, and to try to rest and sleep a little, because that was the warmest place, the walls of the stall cut off the draft that got everywhere else, and manners kept people from asking questions.

Two women came in, way late, probably dock maintenance: she heard the murmur of voices, the curses, the discussion about some man in the crew they had their eye on. They sounded drunk. They went away. That was the only traffic, and Bet drowsed, catnapping, thinking that tomorrow evening, she could go to a vending machine and put that one cred in a slot and have a hot can of soupc start with that. She'd had experience with hunger.

Keep to the liquids when you came off starvation, do a little at a time, nothing greasy.

Her stomach was working on the dissolved wafer and the third of a cup of coca, not sure how to cope with what it had.

The docks outside entered a quiet time then, less noise of machinery and transports moving outside. Alterday on Thule was hardly worth the wake-time. Hardly any of the offices stayed open on that shift, no ship traffic was in to make it necessary, the few bars were mostly empty. Early on, when she'd had a few chits left, she'd gone into bars to keep warm. Docks were always cold, every dock ever built would freeze your ass off. Thule-alterday shut down just like some old Earth town going into night, and the general lack of machinery working all over Thule during that off-shift, she reckoned, and the demand of all the people back in their apartments for heat, meant a fierce chill-down in the dockside air. Which meant stationers were even less likely to be down here during main-night, and station scheduling didn't care to do anything about it.

So nothing got loaded out there, nothing got signed, moved, done, anywhere on the docks until maindawn brought the lights up. Thule was dying. The Earth trade opened up again after the War, but Thule had turned out to be superfluous, the run had drawn a few big new super-freighters like Dublin Again, that could short-cut right past the Hinder Stars, and the discovery of a new dark mass further on from Bryant's meant a bypass for Thule, Venture, Glory and Beta, which was over half the re-opened stations at one stroke.

A route straight to Earth via Bryant's, straight past the place Ernestinehad left her, the Old Man apologetic, saying, "Don't be a fool, Bet. We've got to go back to Pell, is all.