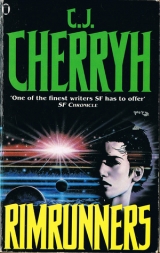

Текст книги "Rimrunners "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Just get the supplies she needed, look respectable enough to impress Mary Gold, work to the next port, and just try to make herself useful enough to stay on—anywhere, any port but Pell—that being Norway'sport.

That was why she'd told old Kato she was staying, because Ernestinewas going back.

And Kato had believed the crap about her wanting to take her chances on the Rim, but Kato had desperate business to do at Pell and a ship in debt and Kato left her for a fool, good luck, mate, stay out of trouble, hope you find your luck.

Hell.

She went back to Ritterman's apartment, she read the messages on the comp, which was only a notice from station library that tapes were overdue. She found the ones the library wanted back, she laid them on the table, to take out and dump in the return the next morning, she looked the address up in the station directory to be able to find it.

And she kept the vid tuned to station traffic ops, always hoping, while she made down a comfortable bed on the couch and drank Ritterman's vodka, ate Ritterman's chips and candy and read Ritterman's skutty picture-books till bedtime.

Back to the docks the next morning, down to the row of vending machines spinward of the lift. She had her mouth full of cheese puffs when the bell rang, that loud long burst that meant a ship had just dropped into system; and she gulped it down with a mouthful of soda and took a breath.

So she made her leisurely stroll toward the corner where the public monitor was, because it was just the longscan had gotten the info from the zenith buoy, and that was an hour and a half light away.

Thule was a dim double star, hardly more than a moderately treacherous jump point, no traffic: the buoy was close-in, and that ship, if it was Mary Gold, a day and a half early, had probably just shaved a quick lighthour or so off that distance in the V-dumps since that information had started on its way to Thule Central. Which still put her some hours out at realspace V, and a long, long burn to go, plus another hour on docking once she got close-in.

A cold-hauler, Mary Gold, just the regular supply run out from Pell. And on from here to Bryant's, that was the schedule. Moving less mass than expected, she reckoned: that could speed a ship up a day, easy. Thank God.

But when she got to the corner where the monitor gave its tired, gray cycles of information, the shipname was AS Loki.

Her heart ticked, just a single bewildered jolt.

Who in hell is Loki?

She stopped, ate a couple of cheese puffs, washed them down and stared at the progress marker on the vid. She wasn't the only one. Dock workers gathered around to wonder.

It was coming in smartly enough. It was an Alliance ship designation.

Her stomach felt upset. She heard somebody speculate it was a Unionside merchanter, just come into the Alliance.

Not unless it was some damn tiny ship, she thought, something come in from some godforsaken arm like Wyatt's Star, clear on Union's backside: she knew every shipname that was worth knowing, knew the Family name, the cargo-class—and the armament class. Down in Africa's'tween-decks, shipnames and capabilities were a running topic.

The skuts in the 'decks might not be able to do a thing in a ship-fight, but if you were down there strapped into your rack and your ship was going into a firefight, what the cap was on the other ship was a real important topic; and if you were going to have to board after that, go onto some merchanter's deck into twisty little corridors full of ambushes, you liked to know those little details. Damn right.

She ate her cheese puffs, she watched the data unfold—then suddenly she remembered the time and she ducked out of the crowd and hurried on down to the Registry.

"I wondered if you were coming in today," Nan said, at her desk as she slipped in the door.

"Sorry." There was a reg about eating and drinking in the front office. "Breakfast. I'll dump this in the can. 'Scuse."

"You know what ship that is?" Nan asked.

She shook her head. "Thought I knew 'em all. Spooks." Trooper word. It was getting to be common, since the War, but she wished she hadn't said that. She oozed past Nan and into the back hall, where Ely met her and asked, "You know that ship?"

"Just saying: no, sir. New one."

Ely looked worried. Well he should. She went on into the back-office work area, tipped the last of the puff-crumbs into her mouth and washed them down with the dregs of the soda, chucked the foil and the can into the cycle-bin before she walked out where the vid was.

Where everybody was: Ely, Nan, the three other clients looking for jobs this morning, all standing, all watching the vid and not saying a thing, except she got looks from the three stationers that maybe added her up as an honest-to-God spacer and maybe a source of information.

"Do you know—?" one started to ask her.

She shook her head. "New to me, mate. No idea." She folded her arms and looked at the numbers, heard one of the stationers say that looked like an all-right approach, the numbers didn't look like a strike-run.

Depends, station-woman. Depends on the mass. Entry vector. Lot of things, damnfool.

Sometimes you got to maneuver. And we lied to those buoys, damn if we didn't.

She watched, standing there with her arms folded, thinking, the way the stationers around her had to be thinking, that it could be one of the Fleet; feeling, the way the stationers certainly weren't, a little stomach-unsettling hope that it was one of Mazian's ships.

Hope like hell it wasn't a Fleet ship going to pull a strike for some reason, and hole the station.

And hope while she was at it that any minute that single blip was going to start shedding other blips, that that screen was going to go red and start flashing a take-cover, and Africaitself, with its riderships deployed, was going to be on station com, old Junker Phillips himself telling a panicked Thule Station that a Fleet ship was going to dock, like it or not.

She watched. She bit her lip and shook her head when one of the stationers asked her about the numbers. She listened while the com-flow from station intersected the comflow from the incomer, all cool ops, station asking the intruder for further ID and a statement of intent, the intruder within a few minutes light, now, but going much, much slower.

Decel continuing, the numbers said.

"Huh," she said finally, figuring there was nothing much going to happen for a while, so she went over and sat down, which got a momentary attention from the stationers, who looked at her as if they hoped that meant something good.

So she relaxed. Watching on vid, waiting to see, was hell and away more comfortable than they'd gotten between-decks, just the audio, the com telling them what they absolutely needed to know, while the ship pulled Gand racks and paneling groaned like the pinnings were going and somebody's gear that had been loose when the takehold rang became a flock of missiles.

Nan and Ely drifted back to work. One of the job-seekers went over to the counter to finish an application, but the other two just stood there looking up at the vid.

" This isLoki command," the vid said finally, amid the muted, static-ridden comflow that had been coming through. " Clear on your instructions, Thule Station. We're a fifteen tank, running way down."

God. No small tank on that thing.

" This is Thule Stationmaster. We've got a scheduled ship-call, Loki, we can do a partial."

Bet sat there with her feet in a scarred plastic chair and listened, with her heart picking up its beats, brain racing with the figures while the timelag of ship and station narrowed, but not enough.

An unknown and a tank that size. Claiming Alliance registry.

Thule Control reported the incomer had done the scheduled burn.

" Thule Stationmaster," the same voice came over the com, finally, " this isLoki command. We're carrying a priority on that fill. Request you route us to your main berth."

The stationers finally figured out priority. There was a sudden tension in them. Bet sat there with her feet up, arms folded, knowing it was still going to be a while, with her heart thumping away in leaden, before-the-strike calm.

Priority. There was only one berth on Thule with a pump fitting that was going to accommodate a starship. The pump was two hundred years old and it managed, but it was slow, and the station tanks were nowhere near capable of turning two large-cap ships in the same week—it took timefor Thule's three skimmers and the mass-driver to bring in a ship-tank load of ice.

If that ship was priority and if it was Alliance, then it was something recommissioned, something Mallory herself might have sent, if it was telling the truth and it wasn't just talking itself into dock to blow them all to hell.

And if it was official, and if it was sitting there for the five days it was likely to take drinking Thule's tanks down to the dregs, there was no way in hell a freighter like Mary Goldwas going to get into that single useable berth and out again for another week.

Or two or three.

Information trickled out of Station Central. Central got a vid image. "God," Nan said when that came up, and Bet just sat there with her arms crossed on a nervous stomach.

Small crew-quarters, a bare, lean spine, and an engine-pack larger than need be.

"What in hell?" Bet said, to a handful of nervous civ stationers, and put a foot on the floor suddenly. "Damn, what class is that thing?"

Ely was out of his office again, coming out to look at the vid in this room, which showed the same thing as the vid in the office. People tended to cluster when they thought they might be blown away.

"Oh, God, oh, God," one of the clients kept saying.

Bet got up while the comflow ran on the audio, business-as-ordinary, with an apparent warship coming in to dock.

"Bet," Nan said. "What is it?"

"Dunno," she said. "Dunno." Her eyes desperately worked over the shadowy detail, the midships area, the huge vanes. "She's some kind of re-fit."

"Whose?" a civ asked.

Bet shook her head. "Dunno that. It's a re-fit, could be anything."

"Whose side?" someone asked.

"Could be anything," she said again. "Never seen her. Never see ships in deep space.

Just hear them. Just talk to 'em in the dark." She hugged her arms around herself and made herself calm down and sit down on the table edge, thinking that there was in fact no telling. It was whatever it wanted to be. Spook was a breed, not a loyalty.

But there was no likelihood it was going to open fire and blow the station. Not if it wanted those tanks filled. Not if its tanks were really that far down. Either it was hauling mass that didn't show or it'd been a long, long run out there.

The comflow kept up. The stationer-folk huddled in front of the vid, remembering whatever stationers remembered, who'd been through too much hell, too many shifts, too much war.

Not fools. Not cowards. Just people who'd been targets once too often, on stations that had no defense at all.

Bet kept her arms clenched, her heart beating in a panic of her own that had nothing to do with stationer reasons.

CHAPTER 5

IT TOOK TIME to get anything into dock at Thule—minimum assists, a small station. The process dragged on, a long series of arcane, quiet communications between the incomer and Station Central, long silences while the station computers and the incomer's talked and sorted things out. That was normal. That relieved the stationers of their worst fears, seeing that the incomer was actually coming in instead of shooting.

So things moved out on the docks, people began to separate themselves a little from available vids: Bet went out for her lunch, down to the vending machines by the lifts.

She got looks from the office types—as if suddenly anybody who looked like a spacer was significant, whether or not she could possibly come from that ship. She ignored the looks, got her chips and her sandwich and her soda, tucked the chips into her pocket and walked out on Thule's little number one dock, where a cluster of lights blazed white on the gantry, spotting the area where dockworkers went about their prep, Thule's usual muddled, seldom-flexed system of operations.

She gave a disgusted twitch of her shoulders, looked at that port, swallowed bites of sandwich and washed them down with soda.

Damn, that ship was a problem, it was a major Problem, it bid fair to cost her neck. It was probably Alliance, all right, her luck had been like that for two years, but her heart was beating faster, her blood was moving in a way it hadn't in a long time. Damn thing could kill her. Damn thing could be the reason the law finally hauled her in and went over her and got her held for Mallory, but it was like she could stand here, and part of her was already on the other side of that wall, already with that ship—and if it killed her it still gave her that feeling a while.

"Shit," she muttered, because it was a damnfool thing to feel, and it muddled up her thinking, so that she could smell the smells and feel the slam of Gwhen the ship moved and hear the sounds again—

She swallowed down the sandwich, she looked at that dock and she was there, that was all, and scared of dying and less scared, she wasn't sure why.

But she went back to Nan and stood by her desk with her back to the locals the other side of the counter and said, "Nan, I got to try for this one."

"Bet, it's a rimrunner. We got a freighter coming in—it's going to behere. This thing—"

Like she was talking to some drugger with a high in sight—

But: "I got to," she said. "I got to, Nan."

For reasons that made her a little crazy, for certain; but crazy enough to have the nerve—like the Bet Yeager that Nan and Ely had been dealing with and the Bet Yeager who was talking now were two different things, but she was sane enough to go back to friends, sane enough to know she didn't want to alienate the only help she had if things went sour.

"You turn 'em in my request?" Bet asked. "Nan?"

"Yeah," Nan said under her breath, looking truly worried over her, the way not many ever had in her life.

So she left.

The dockside swarmed with activity, the dull machinery gleaming under the floods, crews working to complete the connections, in Thule's jury-rigged accommodation for a modern starship. It wasn't a place for spectators. There were few of them. Thule's inhabitants remembered sorties, remembered bodies lying on the decking, shots lighting the smoke, and there were no idle onlookers—just the crews who had work finally, and the usual customs agent, and no more than that.

Excepting herself, who kept to the shadows of the girders, hands in pockets, and watched things proceeding. She inhaled the icy, oil-scented air, watched the pale gray monitor up on top of the pump control box ticking away the numbers, and felt alive for a while.

The whole dock thundered to the sound of the grapples going out, hydraulics screamed and squealed, the boom groaned, and finally the crash of contact carried back down the arms, right through the deck plating and up into an onlooker's bones.

Soft dock, considering the tiny size of the Thule docking cone and the tinsel thinness of little Thule's outer wall: damn ticklish maneuver, another reason the dock was generally vacant. There wasthe remote chance of a bump breaching the wall. But there was equally well a chance of a pump blowing under the load or God knew what else, a dozen ways to get blown to hell and gone anywhere on Thule. Today it failed to matter.

She thought that she could, perhaps, a major perhaps, go the round of vending machines and buy up food enough and stash it here and there in the crannies of Thule docks, maybe go to cover if somebody got onto what was in Ritter-man's bedroom. She could just ignore this ship, wait it out and hope to talk her way onto Mary Goldwhen and if she came. That was the hole card she kept for herself, if Lokiwas what she was afraid it was.

But Mary Goldhad become a small chance, a nothing chance with too many risks of its own.

She waited, she waited two hours until little Thule got its seal problem corrected and got Lokisnugged in and safe. She stood there very glad of Ritterman's castoffs under the jumpsuit, made as it had been for dockside chill: breath still frosted and exposed skin went numb, and she kept her hands in her pockets. Ice patched the corrugated decking, and the leaky seal that was dripping water at the gantry-top was going to breed one helluva icicle in five days' dock time.

Finally the tube went into place, the hatch whined and boomed open, letting out a light touch of warmer, different air, a little pressure release; and of course it was the customs man first up the ramp.

She found a place to sit in the vee of a girder, cold as it was, she sat and she watched, and finally the customs man came out again.

She shivered, she felt—God, a sense of belonging to something again, just being perched out here freezing her backside, like a dozen other sit-and-waits she remembered.

And it wasdamn foolish even to start thinking that way. It was suicidal.

But she wasn't scared, not beyond a flutter in the gut which was her common sense and the uncertainty of the situation; she wasn't scared, she was just waiting to risk her neck, that was all, she thought about where she'd been and where she could go, and it was all still remote from here.

She heard the inside lock open again, heard someone coming. Two of the crew this time, in nondescript, notmilitary. Her heart beat faster and faster as she watched them meet with the dock-chief, all the slow talk that usually went on.

More crew came down. More nondescript, nothing like a uniform, no family resemblance either. She worked cold hands, got up from her wedged-in perch between the girders and shook the feeling back into her legs, then put her hands in her pockets and walked up to the latest couple off the ramp.

"You!" a dockworker called out.

But she ignored that. She walked up, nodded a friendly hello—it was a man on rejuv and a woman headed there, both in brown coveralls, nothing flashy. Work stuff. " 'Day,"

she said. "Welcome in. I'm looking. Got any chance?"

Not particularly friendly faces. "No passengers," the man said.

She touched her pocket where the letter was. "Machinist. Stuck here. Who do I talk to?"

A long slow look, from a cold, deeply creased face; from a hollow-cheeked female face with a burn scar on the side.

"Talk to me," the man said. "Name's Fitch. First officer."

"Yes, sir." She took a breath and slipped her hands back into her pockets, a twitch away from parade rest. Damn. Relax. Civ. Dammit. "Name's Yeager. Off Ernestine.

Junior-most and they had to trim crew. Others got hire, but it's been slim for about six months."

"Not particularly hiring," Fitch said.

"I'm desperate." She kept a tight jaw, breathing shallow. "I'll take scut. I don't ask a share."

A slow, analyzing stare, head to foot and back again—like he was figuring goods and bads in what he was looking at.

"Dunno," Fitch said then, and hooked a quick gesture toward the ramp. "Talk to the Man."

She was half-numb from standing in the airlock, in the kind of dry cold that froze up any water vapor into a white rime on the surfaces and left the knees locking up and refusing to work when she stepped over the threshold into Loki'sdim gut. The knees had gotten to the shaking stage when she got through into the ring (there looked to be only one corridor) and did a drunken walk down the narrow burn-deck. There was one light showing, one door standing open, besides the hatches that were probably the downside stowage.

She reached it, saw the blond, smallish man at the desk. Plain brown jumpsuit. The gimbaled floor made a knee-high step-up. She stood in the corridor and called up,

"Looking for the captain."

"You got him," the Man said, and looked down at her from the desk, so she stepped up by the toehold in the rim of the deck and ducked to clear the door.

"Bet Yeager, sir." Fitch's name had gotten her inside. Now she was shivering, her teeth trying to chatter, not entirely from the cold. "Machinist. Freighter experience.

Looking for a berth, sir."

"Any good?"

"Yes, sir."

A long silence. Pale eyes raked her over. A thin hand turned palm up.

She reached to her pocket and pulled out her papers, trying not to let her hand shake when she put the folder in his hand.

He opened it, unfolded the paper, read it without expression, looked on the back—

everyone did, the last few signatures. And folded it again and gave it back.

"We're not a freighter," he said.

"Yes, sir."

"But maybe you're not spacer."

"I am, sir."

"You know what we are?"

"I think I do, sir."

A long silence. Thin fingers turned the stylus over and over. "What rating?"

"Third, sir."

More silence. The stylus kept turning. "We don't pay standard. You get a hundred a day on leave. Period. Board-call goes out ten hours before undock. My name's Wolfe.

Any questions?"

"No, sir."

"That's the right answer. Remember that. Anything else?"

"No, sir."

"See you, Yeager."

"Yes, sir," she said. And ducked her head and got out, off the deck, down the corridor, out of the ship, still numb.

She thought about going to the Registry. She wanteda drink, she wantedto go out on the docks with a little in her pocket and hit the bars and get a little of the cold out of her bones, but she was a stranger to Lokicrew and she could not use Ritterman's card.

So she went back to the apartment and made herself a stiff one.

Lokiwas no freighter. The captain told that one right. She was still shaken, the old nerves still answered. Lokiwasn't a name she knew, but the name might not have been Lokisix months ago, or the same as that a year ago. The frame was one of the old, old ones by the look of its guts, a small can-hauler with oversized tanks where the cans ought to be, something naturally oversized in its engine pack—tanks easy come by, easy to cobble on even for a half-assed shipyard like Viking, which had built three such ships the Fleet knew about—ships to lie out and lurk in the dark of various jump-points, to run again "with information.

Except the Line was shady, and the spooks went this side and that of it, and the Fleet had trusted them no more than Union had: if you pulled into a point where a spook was, you took it out and asked no questions.

So this particular spook was all official in the Alliance. The free-merchanters had put themselves a boycott together, the merchanters had taken over Pell, and now the spooks the stations had built to keep themselves informed came out in the open, government papers and everything.

Damned right the captain wasn't going to quibble about her papers. When somebody shiny bright and proper came in there looking for a berth, that was the time Lokimight ask real close questions.

She sipped Ritterman's whiskey. And tried not to think that, spook or not, it was about as good as joining up with Mallory. She had to stop the little twitches, like the one that said stand square, like the sirand the ma'am, like the little orderly habits with her gear that said military—

So they were Mallory's spies, most probably—but not withMallory, not toolegitimate, since spooks had regularly sold information to any bidder. And going onto that ship was a case of hiding in plain sight. If she could learn the moves, learn the accent, learn a spook's ways—then she could get along on a spook ship, damn sure she could.

Dangerous. But in some ways less dangerous a hire than on some merchanter on the up and up, with a crew that expected a merchanter brat to know a lot of things, things about posts she'd never touched, especially about cargo regs and station law, things that never had been her business.

She had stood real close to Africa'sOld Man once or twice. A couple of thousand troops in Africa'sgut, and Porey rarely put his nose down there, except he went with them when they went out onto some other deck, Porey was always right in the middle of it; and being close to him that couple of times—she'd gotten the force of him, gotten right fast the idea whyhe was the Old Man, and why everybody jumped when Porey said move. Porey was the damn-coldest man she had ever stood next to; and maybe it was only how desperate she was and how Lokiwas the hope she'd thrown double or nothing on, but this Wolfe, the way he moved, the way he talked—said competent, said no-nonsense, said he was a real bastard and you didn't get any room with him. And that touched old nerves. She knew exactly where she was with him, cut your throat for a bet, but show him you were good and you just might do all right with a captain like that.

Spook captain. That Fitch, that Fitch was no easy man, either. That woman with him you didn't push. That told you something about the captain too.

She poured herself another glass. Maybe, she thought, she was crazy. She wasn't sure whether she ought not just drop out of sight now until the board-call rang, stay mostly in the apartment, not go back to the Registry at all—except she wanted to keep that card of Ritterman's active and she didn't want any chance of getting an inquiry going into Ritterman's inactivity.

Five days, at least, for Loki'stanks to fill. Maybe closer to four till boarding, counting the ten hour boarding-call. If she could just keep things quiet that long, do the daily run to the vending machines, back to the apartment, and stay put, then everything would work out.

All she had to do was stick it out and check the comp for things like overdue tapes, things that could require Ritterman's intervention.

Meanwhile she got out Ritterman's collection of fiches and started sorting. That kind of trade goods was low-mass, it would pack real easy, Thule customs only worried about guns and power-packs and knives and razor-wire and explosives, that kind of thing, it had no duty on anything, and there were no regs on Thule about liquor.

She started packing, at least the sorting part.

She bedded down, the way she had been doing, on Ritterman's couch, she watched a vid, she drank herself stupid and she woke up with a headache and the absolutely true memory that she had a berth.

Best damn night she'd had in half a year.

CHAPTER 6

SHE MADE the morning trip to the vending machines, she lived off chips and soda and cheese sandwiches she heated and added Ritterman's pickles and sauce to. That was the second day down. She stayed in the apartment otherwise and she went through everything in the cluttered front rooms, to see what was worth leaving with.

She checked the comp, she drank, she had another cheese sandwich for supper, she looked at skuz pictures and she made a hook and fixed up the one of Ritterman's useable sweaters that was really snagged—like ship, a lot. You tinkered with stuff, you mended, you washed, you did the drill, you scrubbed anything that didn't fight back, but hell if she was going to give Ritterman a good rep by cleaning up this pit: she just kicked his stuff out of her way and washed what she was going to drink out of.

But that night sleep came harder, and the level in the vodka bottle went down markedly before she could rest.

She kept thinking about immigration and the one formality there was, that she was going to have to log out of station records to get by that customs man. Right now she might be hard to find, on Ritterman's card, in Ritterman's apartment, with not even the Registry knowing where she was right now and only Nan and Ely able to connect her name to her face—but all of that changed the moment she had to hand dockside customs that temporary ID card of hers and that customs man sent the information back through the station computers, right from a terminal on dockside, to be sure she was who she said.

The one thing Alliance was touchy about besides weapons was people, because Mariner and Pan-paris had learned the hard way that people were much more dangerous—the kind of people who came and went under wrong names and false IDs, at the orders of people parsecs away. Customs insisted on checking crew IDs: they'd checked her onto Thule off Ernestineand they'd check her off and onto Loki.

And that check, if anyone was looking for her, if they had any questions about her fingerprints among a hundred others, if the customs man himself had any interest in why her face showed marks—

She tried to think of a way to dodge that check, like maybe going down to Thule's few bars, finding Loki'screw, maybe sleeping over with somebody and maybe talking her way into an early boarding that might miss customs altogether, if Lokiwould cooperate—

But doing anything that might make Lokiback off taking her on, that scared her more than the check-out did.

Besides, getting in with the crew during liberty took money she didn't have, and a body was expected to stand her own bar-bill.

She had certainly fallen asleep with worse prospects on her mind, but solitude was a new affliction. Her mind kept going back to old shipmates on Africa, wondering if they were still alive, wondering whether the major was, and who Bieji Hager was sleeping with now.

Teo was dead. Blown to cold space. So was Joey Schmidt and Yung Kim and a thousand more, at least.

DamnMallory.

So here she was, taking a berth on a spook ship, one that might be on Mallory's orders to boot. So maybe it was fair pay to old debts, if they ended up saving her neck. She imagined Teo shaking his head about what she was doing, but Teo would say, Shit, Bet, dead don't count. And Teo would never blame her.

She tossed over onto her belly and tried to not to think, period, just tried to go away, just go nothing, nowhere, like when the G-stress was going to hit soon and the missiles were going to fly and if you were a skut in a carrier's between-decks, you just rode it out and let the tekkies keep the ship from getting hit.

Damn right.

Fourth day. She got up, stumbled across the clutter in the apartment and checked the public ops channel on Ritterman's vid to see when the board-call was posted. M/D 2100, it said. Fill 97% complete.

Thank God, thank God. Mary Goldwas in, now, Mary Goldhad made it into Thule's system during the night; and the vid said: Condition hold, which meant that Mary Goldwas taking a slow approach, lazing along and probably damn mad and desperate, figuring on a fast turn-around and instead finding out they could be weeks down on their schedule—the same way that Bryant's Star Station, next on Mary Gold'sroute, was going to find its essential supplies a month late; and so was everybody else down the line. A little schedule slip at a place like Pell, a huge, modern station—that was nothing. But herec