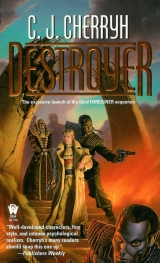

Текст книги "Destroyer "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

No one was disposed to linger in the least. They made as rapid a transit as possible, along hand-lines rigged to take them to the appropriate entry port, through the weightless dark. Breath froze, making smaller clouds in the spotlights. Parka-clad atevi shuttle crew, spotlighted in a flood, emerged at the other end of that line to assure their safety, to take their small items of hand baggage from cold-stiffened hands, and to see them into the shuttle airlock, which itself showed as a patch of white and brilliant inner light in an otherwise enveloping dark.

“Other baggage is coming, nadiin,” Tano informed the crew, “in the next lift, with Lord Geigi’s staff.”

As the bright light inside challenged their eyes and warm, ordinarily humid air met the lungs, it made both seeing and steady breathing difficult for a moment. The station shuttle dock had had numerous improvements on the drawing board, a pressurized tube planned, first of all, to make the transit to shuttles easier and safer, but clearly none of those things had happened, as so much had not happened in the last two years.

But in the faces of the shuttle crew, the only functional atevi shuttle crew, was an absolute commitment, a joy, even, in seeing them—a fervent hope of their situation set to rights, an absolute confidence that they were carrying the necessary answer back to a waiting world.

Bren wasn’t personally that confident.

Not this time.

Chapter 4

“Welcome home, nandiin,” the atevi crew bade them over the intercom, just before their launch away from the station—an auspicious launch, Bren hoped, all considering. The baji-naji emblem, that portrayal of the motive principles of the universe, chance and fortune, still decorated the bulkhead of the shuttle, still reminded them the universe, always in delicate balance, had its odd moments and was subject to forces no one could restrain—that the most secure situation and the most impossible alike could fall suddenly into chaos… but must exit that chaos into order, the eternal swing between the two states.

Some optimist among the crew or the techs had arranged flowers in a well-secured vase on a well-secured shelf below that emblem—life and welcome, that arrangement meant; but one blossom came askew during undock, leaving good fortune momentarily adrift.

And in that extremity, young Cajeiri undertook a zero-g mission, on permission from his great-grandmother to chase it and restore it to its proper and fortunate place in the arrangement. It gave a too-well-behaved young lad at the bitter end of his patience a chance to be up and moving, now that the shuttle was out and away. He succeeded quickly, a triumph, then took his time returning to relative safety in the seats, to everyone’s relief. Cajeiri’s spirits had risen, at least enough for him to become a modest worry to his elders.

The steward then began to serve tea, a fussy, acrobatic operation, unusually early service insofar as anything in the shuttle passenger program had had time to become usual. And once they had had their tea, up front in the cockpit, the pilots greatly yearned, one was coyly informed by said steward, to hear any information they were willing to give them about their voyage to the stars.

“There were foreigners!” Cajeiri exclaimed immediately, brightening, by no means a report designed to settle the crew’s curiosity, and breaching security at a stroke. Baji-naji, from order to potential chaos, in the person of a young boy. “They were nearly as tall as we are! And huge around!”

The steward was, of course, entranced, and at once had a thousand questions more—information for the pilots, of course.

So Ilisidi’s second-senior bodyguard went forward to the shuttle cockpit to regale the whole crew with the details, by the dowager’s personal dispensation, all with, of course, personal cautions against spreading the gossip. In this elite and security-conscious crew it was even foreseeable that the information would stay contained—and Ilisidi’s young man remained up there for some time, doubtless questioned and requestioned until he was hoarse, and very likely enjoying his hero’s status, the shuttle crew with their yearning for information on their voyage and everything that was out there, and the young Assassin just as anxious to understand the shuttle’s workings and to find out in some detail how the space program had survived the troubles on the planet…

And whether they had allies still in any position of authority—such, at least, were the questions Bren himself was sure he would ask, and might yet ask, if the young man didn’t come back with the answers. Certainly information flowed both ways up there, and meanwhile Banichi and Jago, with their own electronics, became very quiet, staring straight ahead of them, of course following all of it from their seats, and absorbing everything.

The details of the shuttle’s operation, however, were not among the things Bren needed to ask anyone. Having translated the shuttle plans and most of the flight operations manual, with the assistance of his staff, and having trained the translators who had mediated the finer details of the actual operations, he knew the facts down to the length of the Jackson runway; he knew that it was 20 feet shorter than the original plan, he knew the names of the grafting bastards responsible, and he really had not rather think about that old issue right now.

He decided to divert himself with his computer, with, eventually, a nap, at least as well as a sane man could sleep on a vessel hurtling deeper and deeper into the gravitational grip of a very unforgiving planet toward a runway that wasn’t quite what they’d designed.

A shuttle with all its fail-safes was still better than parachutes, he reminded himself. He had, at least, never landed the way Jase had, and the way his ancestors had landed on Mospheira in the first place—by parachute, in a little tin-can capsule. For their ancestors it had been a one-way trip, when they’d rebelled against the iron rule of the old Pilots’ Guild and decided to commit themselves to an inhabited planet, since by then it had been well-established the ship was not going to find its way back home at all. Phoenix, the same ship on which they had just voyaged, had dropped into some anomaly of space-time, or suffered some never-revealed malfunction, and popped a station-building expedition out first of all at a deadly white star. They’d gotten away from that by the skin of their teeth, only to be told, by the ship’s masters, that they had to refuel and commit to more voyages, after which, they began to comprehend, their use was to refuel the ship again and again—living a graceless, gray existence under the rule of a band of men who’d, yes, somehow survived the previous disasters, men who’d somehow not volunteered to sacrifice a thing when the better elements of the crew had given their very lives to get them free and out to this lovely green world and safer sun.

The colonists, finding there was an alternative where they’d arrived, had desperately flung themselves onto an innocent planet whose steam-age civilization naïvely assumed they’d arrived from their moon… had assumed, assumed, assumed, until they went to war with each other and every human still alive ended up in an isolated enclave on the island of Mospheira.

Hence his job, when he wasn’t being Lord of the Heavens. Hence the paidhiin came into being, the translators appointed to interpret not only words, but psychology—to prevent two species who’d originally thought it was easy to understand one another from pouring their technology and their concepts into each other’s heads until the system fractured.

One of a long line of paidhiin who’d served the system, trickling humanity’s advanced technology into atevi hands at a sane pace, trying to make humans live lightly on the planet and not offend atevi beliefs and traditions—he’d tried, at least, to keep the faith.

But had he?

Therein lay the guilt… guilt that in recent hours burrowed itself a wider and wider residency under his heart, laying its foundations the moment he’d heard Tabini had gone down, and growing to a whole suite of rooms when he’d heard Geigi lay out the reasons for Tabini’s downfall. Too much tech and too much change too fast had brought—not war with humans, this time—but an internal calamity to atevi, the fall of the aiji who’d pushed, lifelong, for more tech, more tech, more tech… and made too-quick changes in the atevi way of life to take advantage of it. At some point the paidhi was supposed to have said no, and not to have been so accommodating. That had been his job, for God’s sake. It was why all prior paidhiin had not been so snuggly-close with the atevi leadership. Tabini had had the notion of making his people the technological equals of humans in their island enclave—a technological equality they’d all conceptualized as a good rail system, air traffic crossing the continent, maybe even a computer revolution, in his lifetime.

But then long-lost Phoenix had shown up from deep space, and ownership of the abandoned space station had become an issue. Tabini had been determined to secure it for his own people, entirely understandable, and he had been convinced that if humans got it up and running first they’d never relinquish it to atevi, no matter the justice of their claims. He’d had to move fast to take over leadership not only of the space station… but of the crisis humans confessed they’d precipitated out in deep space.

Step by step, Tabini had waded into hotter and hotter water, all for the sake of protecting his people from the changes humans brought, and the paidhi, who should have said no, wait—stop—

To this hour the paidhi just couldn’t figure what else he could have done.

Average atevi, who, like Banichi, had only just figured out the earth went around the sun, or why they should care, had suddenly become critical to the planetary effort to get back into space. The mainland had the mineral resources and the manufacturing resources to do what the ship could not: supply raw materials and workers to get the space station operating again… and, most critically, the planet had the pilots to fly in atmosphere, an art the spacefarers had flatly forgotten and had no time to relearn.

Atevi had been able to get their manufacturing geared up to handle the crisis. The island enclave of Mospheira had still been debating the matter when the atevi’s first spacecraft lifted off the runway and blasted roof tiles off the eaves of Shejidan.

Change, change, and not just change—change proceeding at breakneck speed through every aspect of atevi life. Mines and factories were opened, sudden wealth created for some districts, with shortages of critical materials and extravagant plenty of new luxuries: Mospheiran society, wrangling over regional advantage and company prerogatives, hadn’t been able to do it, even with the technological advantage. Atevi society, where a strong leader could dictate where new plants were to be built, could balance the economy of regions against regions, equalize the supply and demand—and in so doing, created new values, new economy, new emphasis on manufacturing instead of handcrafting of objects valued for centuries, not even to mention such radical notions as preserved food, instead of food auspiciously and respectfully offered in season, with awareness of one’s debt to the natural world…

Cultural change, religious change, upheaval in the relative importance of provinces and districts, not according to history but according to the mineral wealth and the siting of some new critical facility, partly by the aiji’s grace, partly by the questions of where nature had put the resources. It had all worked. It had been a toboggan ride to a brave new tomorrow, and Tabini’s brilliance had kept everyone prosperous, kept himself in charge, abandoned not a shred of his power and put down every attempt to unseat him…

And had the paidhi objected? He’d superintended Tabini’s rush to modernize, confident Tabini’s management of the economy was going to preserve the traditions as well as create new professions, new Guilds. He’d known he was riding the avalanche, and he’d thought he’d steered Tabini to safety. When the crisis came that called them out to Reunion, he’d left Tabini never more powerful, the Association never more prosperous, the atevi economically and politically equal to humans in every regard, even in relation to the ship-humans on the station. He’d left a people possessed of shuttlecraft and every functioning facility to land and service spacecraft, even building a starship of their own, while Mospheiran humans, across the straits from the mainland, dithered and debated and never had accomplished more than those modifications to the airport at Jackson that would serve as a reserve landing site in emergency… give or take the twenty feet of runway that couldn’t get past certain special interests and the Jackson Municipal Golf Course.

Humans on Mospheira had continued to have mixed feelings about the space station, that was the problem underlying Mospheiran politics. Some were extremely enthusiastic about going back to space, but more were suspicious and resentful of their cousins on the ship. And like the atevi, Mospheirans had mixed feelings, too, about the changes, the haste to turn the entire economy into a space-based push for technological equality with the ship-folk, the trampling of, well, fairly old, if not ancient traditions of Mospheiran life.

He’d foreseen all the objections. He’d hoped both Shawn Tyers, the President of Mospheira, and Tabini-aiji, head of the aishidi’tat, the atevi government, would weather all the storms of discontent at least until they’d been able to get back from their mission to Reunion and report that all this sacrifice and striving had produced a result worth having.

He seemed to have won the bet in the case of his old friend Shawn Tyers, though Shawn’s political survival when he had left had seemed more precarious. Shawn was still in office, despite the volatile politics of the island and all the pressures bearing on him.

He had been disastrously wrong, however, about the atevi side of the equation. Tabini had seemed unassailable, delicately and deftly maneuvering around difficulties, as he always had, having secured the help of such unlikely individuals as his own grandmother, the aiji-dowager, a unifying power of the far east, who might have threatened his reign. He’d begotten an heir, Cajeiri, with an Atageini woman, the Atageini, historically speaking, posing one of the greatest threats to the stability of the aishidi’tat. He’d gotten the crotchety, traditionalist head of the Atageini clan on his side. He’d put down one bad bit of trouble arising in the seafaring south and west, and engaged the gadget-loving western Lord Geigi firmly on his side, in the process, Geigi’s influence being a firm bulwark against trouble in all that curve of western coast. What more could he need than those several allies? Nothing had looked remotely likely to shake Tabini from power.

But Geigi had gone up to orbit, managing the atevi side of the station, while the son of a conspirator, allowed to prosper—Tabini, lately influenced by strong Mospheiran hints that it wasn’t proper or civilized to assassinate the relatives of people who’d tried to kill him—repaid Tabini with treachery.

Spare Murini, he’d asked Tabini. Take the chance. He’d been sensitive to the international, interspecies situation—been sensitive to any perception on the part of Mospheiran or space-faring humans that atevi were less civilized or in any way threatening to humans. Attached to the atevi court, he’d begun to take such accusations of atevi barbarism personally; he’d begun, hadn’t he, to want his atevi to have the respect of his species?

There had been a danger point, if he’d only seen it. But he hadn’t read the winds. He had committed the oldest mistake of joint civilization on the planet—getting distracted by one issue, modernizing too fast, worst of all ignoring atevi hardwiring and ignoring the point that what humans might call barbarism was part and parcel of atevi problem-solving.

What had he tried to promote among atevi? Tolerance of out-clan powers. Therefore tolerance of foreigners. How could an enlightened ruler kill the son of a traitor, simply because of his relatives?

And now that unenlightened son of a rebel, driven, perhaps, by that emotion of man’chi which humans weren’t wired to understand on a gut level, had quite naturally, from an atevi view, turned on the aiji who had spared him.

How much of the aishidi’tat had fractured when that happened? How much pent-up tension in the power structure had just snapped? Classic, absolutely classic atevi behavior.

And what could a human do to mend the damage, when the human in question had made the critical mistakes in the first place, and given his atevi superiors bad advice?

Ilisidi might, with some justification, ask for transport for herself and Tabini’s heir back to her homeland, bidding the paidhi to stay the hell on the island. She might justly tell the paidhi to give her no more advice, certainly not of the quality he’d given Tabini. She hadn’t yet mentioned the word blame, but he was sure she knew a certain amount of this situation was indeed his fault.

And there were no few atevi on the mainland who’d like to explain to him all the mistakes he’d made, he was quite sure of it. By now many of his loyal staff, maybe even Banichi and Jago themselves, were quietly questioning moves he’d made, things they’d accepted.

Now that he had an enforced time to sit and think, not even tea sat easily on his stomach, and sleep, as tired as he was, did not come, no matter how he tried, so the hours stretched on and on, in blacker and blacker thoughts. He ate a bite or two of his supper and found no desire for the rest. He drifted, belted to his seat, in a cabin never quiet—the shuttle had too many fans and pings and beeps for that—but that held a kind of a white, shapeless sound, and permitted far too much calculation.

“Bren-ji, you have not eaten,” Jago observed, loose from her seat for the moment, drifting close to him.

“Later, Jago-ji,” he said. “I shall have it later.”

At the moment he wasn’t sure he could keep another bite down.

But self-blame was a state of indulgence he could not afford. Until Ilisidi did, for well-thought reasons, tell him go to hell, he had to get his wits working and do something constructive, if he could only figure what that was.

So he decided he had best shake the vapors, satisfy Jago, and eat the damned sandwich, bite by bite. Deal with the situation at hand, avoid paralyzing doubt, and try to think of first things first. Try to learn from the mistakes. That was the truly unique view he could bring to the situation. At least he’d had experience in mistakes. He had a very good view, from the bottom of this mental pit, of what they had been, and what not to do twice.

Dry bite of tasteless sandwich. One after the other.

If atevi affairs were to get fixed, the fix had to start from the top of the hierarchy. That was the very point of man’chi. He had to find out what had happened to Tabini, the foremost atevi who’d trusted him, and set things right in that regard, if he had to shoot Murini with his own hand.

There was an ambition worth having. Too late to utterly undo the damage, but at least, if he took Murini out of the picture, as should have been done in the first place, he could free the people of a leader completely undeserving of man’chi, of anyone’s man’chi—in his own admittedly human estimation.

He hadn’t asked himself, in those fast-moving days when the space program had been his only focus, why humans felt guilty if they didn’t spare their enemies, but, more importantly, he hadn’t asked himself why atevi had generally felt extremely guilty if they did. He’d been feeling all warm and smug in his accomplishments in those days, too warm and smug and convinced of his own righteousness ever to ask himself that question… like… do atevi have an expectation of certain behavior on all sides, that might be worth considering?

The human word gratitude had always translated into Ragi, the dictionary blithely said so, as kurdi, root from kur, debt. But what did it mean, derived from the word debt? A feeling of debt for an undue kindness? Good debt or bad debt?

And how was that to translate into atevi actions not within, but across the barriers of man’chi? There was the problem.

And translators previous to him had never questioned whether application of gratitude across man’chi lines was possible—had never taken any within-and-outside-man’chi applications into account because translators before him had never been in a position to see atevi cross those boundaries. Translators before him had never dealt with an aiji as extraordinary as Tabini, whose ambitions had crossed those boundaries and placed him into situations where inside and outside man’chi critically mattered. He hadn’t seen it. Bang! Right in the face, and he hadn’t seen it. None of his predecessors had suggested there might be a problem with the word, that concept, that assumption.

Welcome home, Bren Cameron. Welcome home, on the day all the mistakes suddenly made a difference. Bring the computer up, open the dictionary paidhiin had spent centuries building, and put a significant question mark not only beside that word kurdi, but add a note that every emotional and relational word in the dictionary deserved a number one and a number two entry, an inside meaning and an outside meaning. He’d let his dictionary-making duties slip, thinking they didn’t matter so much as his flashier, newer ones. Lord of the Heavens, he’d become. But where was the clue to his problems? Lurking, as always, in the dictionary, right where he’d begun.

The shuttle made its insertion into atmosphere on a route they’d never used before, so everything was tense. The station confirmed they had clearance from their landing site at Jackson, and from Mospheiran air traffic control in general—it was another worry, that some lunatic Mospheiran with an airplane might take exception to their landing or just, in great admiration, take the unprecedented chance to see a shuttle landing. Both sides of the strait had their patented craziness, and a man who wanted to think about such things could fret himself into deeper and deeper indigestion.

Jago noticed it, and inquired again: “Are you ill, Bren-ji?”

She had put away a fair amount of the offered pre-landing snack, and for answer, he simply gave her his dessert, a prettily wrapped bit of cake. “Would you, Jago-ji? I fear I may weigh my stomach down.”

She knew him. She knew he was worrying. She likely knew he was scared spitless. She floated across the aisle and back a row and shared her acquired pastry with Banichi. Then the two of them gave him analytical looks, and put their heads together and conferred.

The conference drifted up the aisle—literally, as Banichi and Jago floated forward—to Cenedi. Dared one wonder—or worry—that his anxiety might then drift over to the dowager, and reach the eight-year-old heir?

Bren felt his ears grow hot, a flush of thoroughly human embarrassment, and he shot Banichi and Jago a fretful look, trying to get them to desist from advising Cenedi. He signaled Jago, who pretended not to see. Now they were worried because he was worried, and because he had not informed them why.

His bodyguard was a delicately balanced, edged weapon. It was outright wrong to handle such an instrument with anything but precision and caution, and he had leaked human emotion into their situation. He had upset their calculations of the risks, not told them the nature of his worries, possibly tipped them toward distrust of the Mospheirans they might have to deal with.

Well, he could at least patch that problem. He insisted, caught Jago’s eye, and when she had drifted back to him:

“Have no concern for my surly disposition or my appetite, nadi-ji. Flying always upsets me. I particularly dislike it when there may be missiles aimed at us. Imagination quite thoroughly upsets my stomach. But I have confidence in our landing and great confidence in Mospheirans on the ground.”

“Do we rely securely upon the Presidenta?”

She was still ready, ready as Tabini had been, along with all their security, to take his word as truth, when his judgement was necessarily at issue in this whole business, whether he was at all reliable in his estimates of his own people, when he’d been so badly mistaken in reactions on the mainland. But there was no room for second thoughts. Gravity had them. They were headed irrevocably for Jackson, with no other landing site in the whole world available, carrying the most precious cargo atevi had, in the dowager and the (at present) bored, over-sugared, and over-stressed heir of the aishidi’tat.

The paidhi needed to get solid control of his own nerves, that was what. He could only think so many moves ahead, or go crazy trying to calculate the variables to a nicety. There was no calculation possible at present, except that they had to get down and get transportation to a place where they could gather more information.

“We may rely on Shawn,” he said. “The Presidenta remains a strong associate, reliable and, as far as I know, firmly seated in his power. I wish I might tell you the next steps we shall take, but I have been reluctant to discuss any specifics with him, for fear of interception by some less well-disposed party. We shall land, I suppose we shall spend the night near the landing field to consider our options and gather information, and by some means, in the morning, I expect, we shall cross to the continent as rapidly as we can. I trust the Presidenta will arrange a boat—that would be my preference.”

“Safer,” Jago agreed. “Slower transit, but one believes all of us agree. There will be surveillance, but surely more boats than planes go about the strait, particularly under these circumstances. I shall present it to the others.”

“Do so, Jago-ji,” he said, and she sailed forward, pulled herself down to a secure place in the seats forward and spoke gravely to Banichi and Cenedi, who had continued their conference, and doubtless were committing certain key things to memory. It seemed likely a plan was in formation up there—even, likely, a plan as to what they should do if all the paidhi’s assurances fell apart entirely and they were met with gunfire or treachery at highest levels.

The paidhi was out of his element in martial affairs. What his bodyguard was doing up there was certainly more constructive than what he was doing, sitting back, fretting, and nursing his indigestion. High time he opened his computer and set about his own reasonable preparation, raking up details of officials on Mospheira, recalling those in various offices, down to their contact numbers and home addresses. He did that, reminded himself of accesses to certain lords on the mainland, then unbelted and drifted up near the dowager. Floating there, tucking down somewhat into a vacant seat, he asked her in detail about various lords on the mainland, with her estimation of their web of man’chi, and that of their households, to whom they paid allegiance, and of what history, with what marriages and inheritances, reestablishing his command of that mathematics of trust and old grievances.

Certainly young Cajeiri listened with more personal interest than a human child might have mustered, absorbing a set of old, old feuds and seemingly pointless begats, marriages, and business dealings of people he’d never met, most of them now dead. His young lips clamped tight on questions he by now knew not to ask, wisely declining to interrupt the conference of his elders, eyes sparking at this and that name he might remotely know, or a light of understanding dawning at a particular reason this clan avoided that one.

When Ilisidi began enumerating the members of the Atageini household, and included two sisters of Cajeiri’s mother, and an illicit affair and illegitimate child in the extreme youth of Damiri’s youngest sister, Lady Meisi, his young eyes grew as round as moons.

“Who, mani-ma?”

“Deiaja.”

“She is my cousin, mani-ma?” Cajeiri exclaimed—Cajeiri having resided under great-great-uncle Tatiseigi’s roof, not so long before their mission launched.

“And being half Kadigidi, and ill-advised, she is a scoundrel of a youngster,” Ilisidi said darkly, “and a thoroughly bad influence, I have no doubt.”

“She brought me cakes,” Cajeiri said, “when great-uncle said I had to stay in my room. I never heard she was my close cousin.”

Ilisidi had lifted a brow at the business of the cakes, and actually seemed to muse on that small point for an instant before she frowned darkly. “One may read the winds of decades in a tree. Young, it bends to every fickle breeze. Old—it leans increasingly to the persistent summer winds of its growing seasons. Have you never marked this tendency in trees, young aiji?”

“I never have, mani-ma.”

“Do so in future,” Ilisidi said sharply. “Consider the winds that continually blow in the Atageini household, from what direction, and how strong. Grow wise.”

“I should rather have had Artur and Gene come down with me! I might rely on them more than the Atageini, at any time!”

Oh, damn, Bren thought, inwardly bracing himself for a very wintry wind, indeed. That small rebellion was certainly not well considered, coming amid Ilisidi’s remarks about childhood and growing.

“And so you do not trust Deiaja as much these days as once you did.”

“You say we should not rely on her. But the Atageini… ”

“The Atageini remain questionable.”

“Not my mother, mani-ma!”

“Children arrive into such difficult situations. Being born to patch a rift, one necessarily spends years at the bottom of it, looking up and seeing far less of the landscape than one might otherwise see. A wise child will take the word of those with a wider view.”