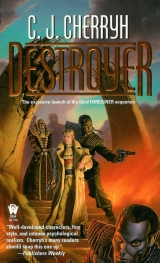

Текст книги "Destroyer "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Man’chi. That emotion. That binding force, that sense of other-self. What had almost been broken was made whole all in an instant: it was a choice of directions and attachments, and there wasn’t a damned thing a father or a mother with safety concerns or a great-grandmother with her own plans could do about it.

A little chill went over him. Do I see what I think I see? he wondered, and was too embarrassed to look toward his own staff, who themselves felt such an intimate thing for him. He’d never actually seen it work—well, there had been the time he had bolted from cover to reach Banichi and Jago under fire, an action that so scandalized their concept of proper behavior that Jago had been willing to shake his teeth out. He had been lucky enough to gain a staff he could absolutely trust, and, from his side, love, but the shift of loyalties had generally been so subtle and so internal with him and his staff, all of them sober, older creatures than teenagers, and while he never doubted deep emotion was there—and felt it—he had never seen a case of man’chi shifting, except in the machimi plays.

But the fact was—those two young people were utterly honest, and Cajeiri was, and there it all was, a life-choice. They hadn’t broken bonds with their family, but they’d formed something else, something that had, in a day, taken over their lives, totally shifted their focus. They were about at that stage when humans hit first love, and had to be counseled and persuaded against tidal forces that could shipwreck their whole lives…

Nothing of sexual attraction, here, not in man’chi. But clearly it was a sort of chemistry, and, a choice might be just as problematic—for Taibeni youngsters dragged into danger of their lives and a Ragi prince who, two years from now, might have made a more mature, political judgement.

“Young persons,” Ilisidi said severely.

“Mani-ma.” Cajeiri pulled his young followers over to Ilisidi, and they bowed, and he bowed, all of which she accepted with a deep frown.

“This will be dangerous, nadiin,” she said to them.

“Yes, aiji-ma,” the young man said.

“Names.”

“Antaro, aiji-ma,” the girl said; and, “Jegari, aiji-ma,” the boy, both under Ilisidi’s head to foot scrutiny.

“What, sixteen?”

“Fifteen, nearly sixteen, aiji-ma.” The boy answered.

Twice Cajeiri’s age. That made no difference in what they felt. It by no means affected rank, or precedence.

“So,” Ilisidi said, and gave a nod and leaned on her cane, then looked at the parents, another exchange of bows, hers and theirs.

And Cajeiri—Cajeiri was incredibly happy, solemn, but his whole being aglow as he went off with his companions—from dejected, he hurried to deal with his own mechieti, to make himself ready, to do everything himself. They wanted to help him, but let him manage what an eight-year-old could.

Jago turned up at Bren’s side, to help him saddle up. So did Tano. They looked solemn, themselves.

He looked a question at them, but they had no immediate answer. There were some things which, if he asked them a plain question, would be several days explaining, and no greater understanding at the end.

Now, God, the parents had to be upset—but they showed no inclination to go along. How could they, if the next ride took them down into Atageini territory, where their presence would not help negotiations at all?

Neither, the thought occurred to him, would this young pair.

Damn, he thought, arriving at, perhaps, the thoughts that were racing through several atevi minds, but never, of course, the young minds in question.

“Nandi.” Algini had his mechieti saddled for him. He took Tano’s help getting up, and hit the saddle with, oh, the expected pain. In the periphery of his vision he saw, to be sure, a leave-taking, Cajeiri with the two Taibeni youngsters, after which Keimi and the parents and everyone else rode away, back toward Taiben lands.

There was a moment of quiet. Then a burst of energy as Cajeiri went to mount up, with his associates’ help, as if the whole world was made new around them. The dowager accepted Cenedi’s assistance to mount, and, curiously, to Bren’s eye, she had a satisfaction about her this morning that said, indeed, she was not that displeased, not nearly as much as their situation might indicate.

So there were still nuances he failed to understand.

They started off, the young people planted firmly in the center of the column, with the dowager, and with him. For a while he listened to Nawari instructing the young people, advising the new arrivals what to do and what contingencies to consider if they should come under fire.

And the dowager sternly advising Cajeiri that if he picked shelter, he should now adjust his thinking and pick shelter wide enough for three.

Hell of a thing, he said to himself. Hell of a thing for three kids to have to think of. The older generation had a few things to answer for.

But then—under different circumstances, they might not have met at all. Man’chi might have fallen out differently. Tabini and Damiri and Ilisidi herself might have carefully managed what susceptible young persons came into contact with the heir, at what times, with careful consideration as to what associations they represented and what possible alliances they brought.

What governs what attraction takes hold? he wondered, without answers. What sets off the spark, that hits one hard at eight, and the other two blithely unattached to any loyalty but their parents, evidently, until they’re midteens?

They hit a long slope, bound downward, now, into the treeless meadowlands. A herd of teigi grazed in the distance. They would not be legitimate prey for another few months, in the atevi rules of season, but the teigi had no instinctive knowledge of seasons and kabiu. Heads went up and the herd bounded off at the first whisper of their presence. The wind had been out of the north, across the slope, though it had been shifting, and now it came full around out of the west, at their backs, in some force. A little spatter of rain came down on them, quickly abated, but with hints of thunder behind them.

They rode down one meadow and up to the crest of a long roll of the land, where they had their first view of the eastern mountains, a blue haze in the distance, above a long slant of meadow and cultivated fields, even the brown stripe of a farm-to-market road. That would lead to some larger town.

They avoided that direction. Wind and rain-spatter at their backs, they turned northeast, toward the heart of Atageini territory, deeper and deeper.

Further and further onto the tolerance and mercy of Lord Tatiseigi, who surely knew by now that intruders had crossed his borders.

Deeper and deeper into danger, the frail dowager, an eight-year-old boy and a pair of Taibeni children—and a human, whom Lord Tatiseigi had only grudgingly tolerated in the first place. Vulnerable, he kept thinking. And vulnerability was entirely unlike Ilisidi—on whom a supplicant’s role sat very, very strangely.

God, he thought. She wouldn’t. Would she?

Would Ilisidi, to protect her great-grandson and secure her own bloodline in the succession, harbor any notion of abandoning Tabini as aiji and joining with Tatiseigi in a coup, a shift of man’chi as sudden, as illogical, and as catastrophic as what he had just witnessed? She had always wanted to rule.

It was a turn straight out of the machimi. Too damn many movies. He was far out of the habit of the classic drama. His thinking had gone into human lines, which had governed politics on the ship. Down here the priorities were very, very different.

“Do I see worry on your face, paidhi-ji?”

“One relies, as ever, on your honesty, aiji-ma. Are we going to Tirnamardi to fight, to negotiate—” Never leave a logical set at ill-omened two. She knew there was a third thing coming. “Or to make new arrangements?”

An aged map of lines rearranged itself subtly, a wicked gleam in her eye. “No one else would dare ask such a question, paidhi.”

“Because atevi follow, aiji-ma. Humans have to figure out the path.”

“Some follow us. Some follow others.”

“But the paidhi has no instinct to tell him which way the wind is blowing, aiji-ma. One assumes there is logic in what you do. May I know what it is?”

“Purity defines you, paidhi-ji. As far as you travel, it always defines you.”

His face flushed slightly. He could not help it. He was indeed very naïve, in certain regards, and knew it, and Ilisidi smiled at him, a subtle smile.

“What you witnessed makes you think of such things, does it, paidhi-aiji?”

“It teaches me. It makes me question what I know.”

“We value you,” she said. “Our compass. Our true lodestone of virtue.”

“One is glad of some usefulness, aiji-ma.” He was not comforted. The old spark had entered the dowager’s eye this morning, ever since that turn of events in the camp. Ilisidi in this mode was dangerous. Lethal.

And sometimes frighteningly honest. She reached out a hand and touched his arm.

“Protect the truth, paidhi-ji. Do not swerve from that. We wondered when, not if, you would come to consult us about the future.”

His face still burned.

“And what future, aiji-ma? One regrets not to know, but one has no understanding at all.”

“Nor will you. Nor can you. Nor can we. We will know when we see Tatiseigi.”

Was it all that nebulous, that much a dice throw, that even Tatiseigi himself would not know until then? Tatiseigi would have to see her. They would have to size one another up, for resolution, strength—and plans, which might include one or the other of them making a power grab.

Or at least thinking about taking hostages.

She rode forward, leaving him, having said as much as she chose to say. He reined back a little.

“It was well done, Bren-ji,” Jago said, riding next to him. “Well done, to speak to her. She had questions about what you might be thinking, which she may have satisfied.”

“I had to try,” he said. “But I learned absolutely nothing. Except that a great deal is still up in the air.”

“Up in the air,” Jago said, amused, sometimes, by his translation of Mosphei’ idiom. “Baji-naji,” she rendered it, the dice-fall of the universe, the give and take in the design.

The design always survived. The pieces might not.

There was quiet in the column after that. The youngsters talked in whispers even human ears could detect over the general noise of movement.

They took to the trees again, a wooded district, Cenedi still leading. When they came out again, on a ridge overlooking a broad expanse of cultivated land, and the distant cluster of small towns, visible clear to the swell of horizon that obscured the eastern mountains, the sun was behind the woods at their backs, and the light was growing dim with twilight. The cloud had begun to rumble with thunder, advising them that clearing the edge of the trees and getting to the lowlands might be a good idea.

Bren absolutely had no idea where they were now. He asked Jago, who gave him village names.

“Within an hour’s ride of estate land,” she said, “at the pace we set.”

“That close.” He was dismayed. He had rather thought they would be getting wet tonight, camping in the open. He was not that much encouraged to know they were that close.

He hoped to God they didn’t run into trouble. He fished after another analgesic. He was sure everyone in the party was suffering, excepting, of course, Antaro and Jegari, who were disgustingly blithe and bright even at this late hour.

At least Cajeiri had someone specifically looking after him and answering his questions, providing him the instinctual moves his two years on the ship hadn’t taught him. Besides them, Nawari was back there, bringing up the rear, protection for the youngsters.

No question that Cenedi, who had been all his career with Ilisidi, was going to stay with her, no matter what happened: he would not divert himself to care for anyone else, come hell or high water, as the saying went.

God, he hoped Tatiseigi had not turned coat.

They started downhill again, and their trail broadened toward dusk, broadened and joined a true road, even a maintained road. The air grew cooler as the sun sank, cooler to the point of chill, with a beginning drizzle, and Bren buttoned his coat.

Another space of riding, and a dark wall, a hedge, loomed across the road, in the gathering dark. He looked concentratedly at it and saw a dim barrier in their path. A gate. A metal-grilled gate.

The estate border. Beyond it—they were on Tirnamardi’s grounds, however far they extended.

“Traps, Tano-ji?” he asked.

“Possibly,” Tano said. Algini had ridden up to speak to Banichi some few moments ago, not unprecedented in their trip, but Algini had a particular expertise in nasty devices. Of Cenedi’s men, only Nawari still hung to the rear.

And Cenedi checked their pace markedly, the closer they came to that gate. At a certain point something exploded with an electric snap, and Bren jumped, the mechieti all jumped, and he fought to bring his beast under control.

“What happened?” The dark and the misting rain obscured the riders ahead into twilight shadows. He was afraid for Banichi and Algini, foremost; and Cenedi: there might be worse. Or they had set something off.

Jago had drawn closer to him. “A discouragement to approach, Bren-ji, not lethal. One never likes to surprise a guard—unless one intends to remove him.”

“Someone is there?” In the gathering dark, in the rain, at this remote remove, he had not expected it.

“Assuredly,” Jago said. “And Banichi did not care to approach unheard. That watcher will pay close attention now.”

“We shall ride right up to the gate?”

“We shall ride up. He will come out.”

Bren bit his lip. The watcher was coming to them, that was to say.

And of a sudden, atevi eyes being the better in the dusk: “Tell your lord he has visitors!” Cenedi shouted into the night.

“Who are you, nadi?” a distant voice asked, somewhere behind the gate, and by now the fore of their column had stopped, the rest of them drifting to a halt behind. They were all too exposed, in Bren’s anxious calculation. And in a heartbeat and a glance, he was not sure where Banichi had gotten to, or Algini.

“Escort to a lady of the lord’s personal acquaintance. Tell him so, nadi!”

“I shall relay that, nadi, but best if I had a name!”

A two-heartbeat pause, then, from Cenedi: “Say he will remember when lightning hit the boat.”

“Lightning hit the boat.” Bren could hear the disbelieving mutter from here, in the general hush. Mechieti snorted and shifted, his own included, and he kept the rein just short of taut, tapping slightly with his quirt to restrain a sideward motion, while someone up there was making a phone call.

“Should we move off the road, Jago-ji?”

“Best stay in the saddle. Keep the quirt ready, Bren-ji. If we move, we move.”

There was a small pause. The guard was undoubtedly Guild, undoubtedly had communications with a station somewhere inside the Atageini house, and was asking questions. He was likely not alone, either. It was not the atevi habit that he be out here alone, and one rather thought that in all the brush grown up against the wall, and overtopping it, there might be a gun aimed at them, as somewhere out there Banichi and Algini had moved into protective position.

“Nandi,” the other side called back, this time in a tone of astonishment, “Lord Tatiseigi is bringing the car.”

“No need for that,” Cenedi said, “if you open the gates, nadi. We can meet him halfway.”

There was another small delay. Then the gates yielded outward with a sullen creak of iron.

Bren drew a deep, deep breath. He asked, on its outflow: “Is this good, Jago-ji?”

And her amused answer: “Certainly better than the alternatives.”

Chapter 9

It was a well-maintained and level road, probably, Bren thought, the route by which the lord’s vehicles, when used, would make the trip to the rural market or to the much-debated train station. Rain spatted down, windblown, and lightning lit the rain-pocked dirt under the mechieti’s feet.

And far in the distance two headlights gleamed, wending their way toward them.

Cajeiri and his two companions came up the column, taking advantage of the wider road, to reach the dowager.

“Is that my great-uncle, mani-ma?” Great-uncle, in the polite imprecision of ordinary usage, was easier and more intimate. He was great-uncle to Cajeiri’s mother.

“It should be, indeed, young gentleman. Straighten your collar.”

“Mani-ma.” Cajeiri quickly adjusted the wildly-flying lace.

Bren did a little tidying of his own. And he was very conscious of the gun in his pocket. He was sure all their staff was on the alert. They had only the gatekeepers’ word that the oncoming car represented a welcome at all.

And the guards had shut the gate behind them.

Further and further into the estate, as that car wended toward them, its headlights at times aimed off into shrubbery, at other times casting diffuse light down onto the road in front of them, at last close enough to spotlight the slanting rain-drops.

“Should there be any unanticipated trouble for us, great-grandson,” the dowager said, speaking in the fortunate first-three-plural, “ride for the outer gate. Rely on Nawari. He will open it.”

“Yes, mani-ma.”

The motorcar was not the most modern and efficient, but certainly it sounded impressive. It had probably gone into service in Wilson’s tenure as paidhi, and probably it had traveled less than the distance from Jackson to the north shore in all its years of operation: Bren reckoned so, knowing Tatiseigi’s ways.

It blinded them with its lights as it rumbled up to them, and the mechieti were far from happy with its racket. They milled about and the sky took that moment to add thunder to the mix.

The car braked. A door opened, and a guard bailed out and moved quickly, bringing a move of hands to weapons, but indeed, it was only to open the passenger door and to assist an elderly gentleman to exit into the rain.

Tatiseigi himself, grim old man, outlined in the headlights: he advanced a few paces, squinting and shading his eyes.

Ilisidi rode forward, keeping her mechieti under tight rein, its uncapped tusks a hazard to everyone it might encounter, no respecter of elderly lords.

“ ’Sidi-ji,” the old man said, frowning into the rain. “It is you.”

“It certainly is,” Ilisidi said sharply, “and a pretty mess the world is in, when your gates are shut and guarded by lethal devices, nandi. Is my rascal grandson here?”

“No,” Tatiseigi said. “No. He has been, but he is not. But you are back from this gallivanting about the heavens. And is that half-grown boy my nephew?”

“One offers deepest respect, great-uncle.” Cajeiri was doing very well controlling a restive and annoyed mechieti, which detested facing the lights and that rumbling engine. “Has there been news from my mother, great-uncle?”

Very damned precocious, for eight. But then, Cajeiri had had his great-grandmother for a tutor non-stop for two years, and lost no time seizing the moral initiative.

“No news,” Tatiseigi said shortly, and somewhat rudely. One was not strictly obliged to courtesy with a forward child, and the old man was being rained upon. “Come to the hall for questions. Come to the hall. The deluge is coming. You might ride with me, ’Sidi-ji.”

“Too much effort to get down and get in and get out,” Ilisidi said. “These old bones prefer a short, painful ride. But a glass of brandy and supper would come very welcome when we arrive, not to mention a warm bath, Tati-ji.”

“Then come ahead. Both are available. Is that the paidhi with you?”

“It is, nandi,” Bren said for himself.

“Instigator of this mess,” Tatiseigi muttered, like a curse, and turned away, headed for his car.

So. It was certainly clear where he stood, and abundantly clear, too, the paidhi could stand out in the oncoming rain for all Tatiseigi cared, but at least Tatiseigi did not exclude him from the invitation… whatever his next intentions.

“He is old,” Jago said, not that it moderated the old man’s discourtesy. The old had license, and some used that license freely.

“He is justified,” Bren said in a low voice. “He is completely justified, as far as things on the ground go, Jago-ji. One fears there is no remedy for his opinion except our setting things back in place.”

Not mentioning there was no particular reluctance to commit assassination under one’s own roof.

Right now they had only Taiben’s advice, predicated on Taiben’s devotedly favorable opinion of the fallen regime. This… this would be the less pleasing side of the matter. Especially as regarded the paidhi-aiji and his influence.

Tatiseigi had gotten in. The car awkwardly executed a turn, mangling a shrub in the process, and lumbered off down the road.

“I wish to try to convince this gentleman, Jago-ji. I wonder if I can do it.”

“Easier to move a mountain,” was Jago’s grim judgement. The man was notorious in the senate and elsewhere as the stiffest-necked, most hidebound lord in the west.

“We shall get the truth from this lord at least,” he said. “And if it should be a hard truth, so much the better for my pursuing it here, under the dowager’s auspices. I doubt he will poison me in her company.”

“One believes she would take strong offense,” Jago said, not at her happiest. “One hopes this is the case, Bren-ji.”

“Be easy, nadi, no matter what he says to me. I shall be glad to hear anything the lord wants to say to me, no matter how insulting, no matter how wrong. How else shall I understand what people think?”

“Indeed,” Jago muttered, not happy with the notion. “The same with his staff, nandi. We shall learn what we can, and politely tolerate what we would never tolerate. Shall we tell others of our Guild, if they ask, the things we have seen, the reasons for our actions?”

It was worth not a moment of consideration. “Yes,” he said. It was what they had to do, ultimately, and the Guild on Tatiseigi’s staff would ask those who had dealt with them. The Guild in Shejidan would need to know, above all else, and they would gather information on a situation—they would constantly gather information, and it needed to be consistent at every level.

They followed the car, no more rapidly than they had formerly ridden, and over the second hill the house itself came into view, lights gleaming through the rain.

House: fortress, rather, not quite in the sense that Malguri was a fortress, of a much older origin, but the Atageini stronghold, Tirnamardi, was a white limestone sprawl of wings and towers, some of which might have snipers at the windows, in such anxious times. The building dated from the age of gunpowder, and even had a cannon or two about the premises, which, he had heard, still fired on festive occasions, and once in the last thirty years, in a territorial dispute with Taiben, making a point, if doing harm only to a tree or two.

The old lord, disdaining modernity, had probably laid in a supply of cannonballs for the current crisis.

The place showed yellow lights from ornate windows, lights that cast rectangles on formally pruned shrubbery and, yes, a cobblestone approach, which the mechieti intensely disliked under their pads. They protested, and Cajeiri’s tended off toward the topiary hedge, intending to cross onto the clipped lawn. Jegari and Antaro rode between, and forestalled it quite deftly.

The car pulled up ahead of them. The great double doors of the house opened wide, and servants poured out onto the steps carrying electric lanterns, no floodlights installed, nothing to scar that historic facade. Gas lights had been the rule here until ten years ago, and the lord had, ever so reluctantly, modernized, only because the gas pipes had gotten too old to be safe, and electrification had been, the deciding point, cheaper to install than new gas pipes.

The lilies of the Atageini ran along the carved stone frame of the doorway atop those steps, tall, leafy stems in bas relief and graceful nodding blooms at the corners, fully defined. Lilies figured at intervals across the facade, and were—he had not noticed it—emblazoned on the black door of the car from which Tatiseigi emerged… parsimonious on technology, profligate with artists, so the reputation of the house was.

Damiri’s ancestral home. But there was no news of her, the old man had said. Has been, but not. Like a will of the wisp, Tabini’s progress through the countryside.

Servants hurried to take charge of the mechieti, who had generally formed predatory intentions against the lush, low topiary hedge. After one mistake, the servants singled out the leader as, not Ilisidi’s, but Cenedi’s. Once they had that increasingly cantankerous mechieti adequately under control from the ground, it was time for all the riders to secure the reins and get down.

Bren’s mechieti had its own ambitions toward the nearby hedge. He whacked it hard with his quirt. His blow might have been a stray breeze, the tug at the rein a mere nuisance. Its mind was set; it was dark, it was thundering and raining, the mechieti knew they were stopping and there should be food in the offing. And with the servants starting to lead the herd off, if he did not get down before they led the leader away, he would be swept ignominiously away, unable to get down before they stopped at the stables, which was not the entry to Lord Tatiseigi’s house he wanted. He slipped his leg across the bow of the serpentine neck, grasped the saddle for safety, and slid down the towering side, holding onto the leathers as he went.

He at least kept his footing on the wet cobbles. Annoyed, his mechieti swung its head back toward him with a dangerous pass of those formidable lower-jaw tusks, then, seeing the herd moving, ignored him for a stolen mouthful of carefully-pruned hedge on the way. He defended the foliage with a whack of the quirt, risking his life and swatting it twice. It moved on.

Jago came hurrying back belatedly to rescue him from the responsibility, the house servants trying to shy other mechieti off the hedges and only adding to the chaos. But the herd leader was clearly being quirted off into the dark, now. Bren got out of the path of two others, forced his legs to bear him, and felt Jago’s hand on his arm, firm and steady.

Thunder echoed off the walls.

“Dry lodgings,” Bren said breathlessly, attempting good cheer, but, God, he was done in. When he asked his limbs to walk, his knees and ankles were entirely unreliable under him. Too much sitting. Too much space travel. And earth’s gravity, reminding him what he did weigh.

Ahead of them, Tatiseigi had gone up the lily-bordered steps with Ilisidi, into the warm electric lamplight inside. Staff had followed. So had Cajeiri, and his two. He climbed, Banichi and the rest of his staff ahead of him, Jago steering him, where no one would notice.

They were, thank God, shallow steps. He reached the top, followed the dowager and her bodyguard, and the three youngsters into a lighted foyer, so warm it stole his breath. The walls had a lily fresco that jogged a dazed memory hard—they were exactly, he realized, like the lilies of the Atageini in their apartment in the Bu-javid. Lilies were prominent everywhere, in bronze on a cabinet, worked into the sconces, rendered in marble around the border of the floor. A visitor was to be aware at every instant under what roof he had come, and know how rich, how powerful this ancient clan was.

Inside, under the many-shadowed lights of the chandelier, there were the necessary greetings, Ilisidi to their host, the formal presentation of her great-grandson—and a scowl on Tatiseigi’s face as he looked over the two young people attending the heir, young people not, evidently to his taste.

“Taibeni,” he said.

“In man’chi to the young lord, nandi,” Ilisidi said sharply—if she and Tatiseigi had had fur, it would have bristled. “And under my protection.”

“They will stay with the young lord,” Tatiseigi said, “and only under those conditions, is it clear, nephew?”

“Yes, great-uncle.”

None of them were fit for polite company, except the two Taibeni, who were at least clean. As for the rest of them, no amount of small fussing could order their clothing into anything like good grace. They, and their baggage, were dripping unto the marble. There were the traces of the dirty, oily truck, fishy ice, of slobbering mechieti, sweat, stove soot, forest leaves, and God knew what else, all tracked into this immaculate hall, along with mud from the rain. But Tatiseigi’s mood had been, for him, warm, even cordial—until he spotted the two Taibeni. Encouraging, Bren said to himself, and noted that there was, unlike their bodyguards’ martial look in this hall, no sign of weapons among the staff, some of which were uniformed Guild. House servants had arrived, too, looking at them from the inside stairs, sizing up the job in some dismay, one might imagine, though nothing showed on their faces.

“We shall accept responsibility for these young people,” Ilisidi said. “But we stand in need of baths. Baths, Tati-ji. Even before brandy. Before supper. One does hope there will be supper.”

“By all means.” Appearing a little mollified, Tatiseigi made a movement of his hand. A servant ran up the marble stairs at high speed. There would be hot water only if the boilers were up. In places of this age, predating the human presence on the planet, boilers were the standard, and they did not operate at all hours. One would assume that if there was hot water, it would go first to the dowager.

Maids among the servants made deep bows, ready to escort the dowager and, odd woman in their party, Jago, upstairs.

“Young gentleman,” Tatiseigi said to Cajeiri, “you will use my own bath.” A signal honor, to a close kinsman, and with a slight disgust: “With your Taibeni. The rest of you, there is a bath backstairs.”

That, in Bren’s ears, certainly said where he belonged, in the mudroom, the bath the house would use coming in from the hunt. And Jago, who had matter-of-factly started to join the dowager in retreat, did not. She came back to him, and with Banichi, Tano, and Algini, formed part of a very unkempt and undigestible lump in the center of the immaculate foyer.