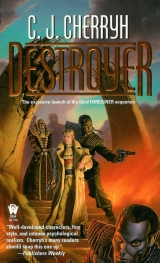

Текст книги "Destroyer "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Destroyer by C. J. Cherryh

Chapter 1

Spider plants had taken over the cabin, cascading sheets of spider plants growing from pots improvised from sealed sections of plastic pipe arranged in racks around the ceiling of every wall. They made showers of green runners and gave out clouds of miniature pale-edged spider babies that swayed in the gusts from vents, in the opening of doors.

The plants were fortunate, kabiu, to atevi sensibilities. They were alive. They grew, they changed, masking steel walls that never changed, and in their increasingly abundant green, they reminded a voyager that ahead of them in the vast deep dark of space was a planet where atevi and humans shared natural breezes, enjoyed meadows and forests and the occasional wild mountain-bred storm, in an environment where, indeed, growth was lush and abundant.

“The planting is becoming extravagant, nandi,” Narani had once suggested, that excellent gentleman, when the pipe-pots were only ten, and ran along only one wall. “Bindanda wishes to inquire if we should simply discard the excess at this point.”

Bren Cameron’s devoted staff had by now offered spider plants to every colonist in the deck above, and bestowed them on every crew cabin that would accept them, where he supposed they likewise proliferated to the limit of tolerance. He had consulted the ship’s lab, to whom he had given the first offshoots, fearing the spread of his house plants might provide lifesupport a real problem… but lifesupport declared that, no, living biomass provided their systems no problem at all, except as they tied up water and nutrients. The ship had plenty of both, and the chief disruption to the closed loop of life aboard Phoenix, so they said, was simply that the plants made “an interesting intervention” in the daily oxygen/carbon dioxide cycle, the energy budget, humidity and climate control. “A catastrophic die-off would be a matter for concern,” lifesupport told him, “but we would of course consume the biomass that might result. Slow changes, we accommodate quite well. We find this an interesting variance in the system. They balance humidity. And they clean the air.”

So the plants grew, and showered out their runners with baby spiders unrestrained over the two years of their voyage, proceeding from one wall, to two, and now four, having found conditions very much to their liking—the plants especially liked their intervals in folded space, such as now, when plants thrived in crazy abundance and intelligent beings operated on minimal intellect. The spider plants cured dry air, static, and nosebleeds, that persistent malady aboard. They were, most of all, alive, and in the metal world of the ship, they were a bizarre sort of hobby.

Pity, Bren thought, that he hadn’t brought along tomatoes instead of inedible house plants, preserved tomatoes having completely run out aboard, in the two-plus years of their voyage—tomato sauce depleted along with other commodities, like the highly favored sugar candies. The better part of three thousand souls aboard consumed a great deal of sugar and fruit, fruit being novel to a spacefaring population, the simplest flavors generally being favored over more complex tastes.

He, himself, was not from a spacefaring population, and he dreaded the day that their daily fare would get down to the yeasts and algaes that had been lonely Reunion Station’s ordinary fare for the few centuries of its existence.

Reunion was now in other hands. Its population was aboard, headed for a refuge and a new life on a station orbiting what they understood to be an Eden, a reservoir of fruit candies and other such delights.

They consumed stores at a higher rate than planned. Now tea was running short. Caffeine was about to run out altogether. That was a crisis.

Bren took his carefully cherished cup—he afforded himself one small pot a day and kept a careful eye on what remained in their stores, knowing that his atevi staff would sacrifice their own ration to provide for him till it ran out, if he did not insist they share.

This late evening as usual, after a very nice dinner, he seated himself at his writing-desk, which supported his computer along with the paper, pen, formal stationery and wax-jack of an atevi gentleman… not the only paper aboard, but close to it. He set his teacup down precisely at the proper spot, just so, opened the computer, and resumed his letters, a tapping of keys so rapid it made a sort of music; it had a rhythm, a living rhythm of his thoughts, like a conversation with himself.

He wore his lightest coat in the snug, pleasantly humidified warmth of his cabin, maintained only a minimum of lace at the cuffs—in the general diminution of intelligence and enterprise, no one stirred much during their transit of folded space, few people went visiting, and entertainments were mostly, during such times, television of the very lowest order. Staff gathered in the dining hall to watch dramas from the human archive… but there were no longer refreshments, under the general rationing, and the whole affair had begun to assume a worn, threadbare cheerfulness, which he usually left early.

He dressed, every day, wore the clothes of a gentleman, which his staff meticulously prepared and laid out daily… the lace now unstarched, that commodity having run short, too, but the shirts carefully ironed, the knee-length coats immaculate. He read in the afternoons. He was learning ancient Greek, long an ambition of his, and working on a kyo grammar—being a linguist, the translator, the paidhi, long before he became Lord of the Heavens. He had been charged with retrieving a few thousand inconvenient colonists and getting them back to safe territory, and in the process he had discovered a further need for his services. He had words. He could make a dictionary and a grammar. He reverted to his old scholarly duties to keep his mind sharp.

He likewise kept up his letters, daily, his evening ritual, along with the after-dinner tea. He had a cyclic record of the rise in the quality of his output during sojourns in normal space, when his brain formed connections, and, longer still, those intervals of folded space, when his prose suffered jumps of logic and grammar and other flaws. In the latter instance he learned that the ship’s crew had a reason for rules and discipline and careful procedure. He found that strict schedule and meticulous procedure afforded his dimmer days a necessary structure, when it was oh so easy to grow slovenly in habit. Rules and formality were increasingly necessary for him and the staff, when getting out of bed these days took an act of moral fortitude.

But every day his staff dressed him completely and properly, no matter that he seldom called on the upstairs neighbors and received no guests. He was their necessary focus, as his letters and his dictionary had become the purpose of his interminable days—and he went through his meticulously ordered daily routine on this day as on over seven hundred days before this. The letters, the one to his brother Toby, and the other to Tabini, aiji of the aishidi’tat, the association of all atevi associations, each totaled above a thousand pages. In all reason, he doubted either his brother or the aiji who had commissioned him to this voyage would ever have the patience to read what amounted to a self-indulgent diary—well, they would read certain key sections he had flagged as significant, but that was not the point of creating it in such detail.

Sanity was. The ability to look up a given day and remember they had made progress.

Dear Toby, he began his day’s account, a peaceful night and a day as dull as yesterday, which, considering our adventures of time past, I still count as good.

What have I done since yesterday?

I solved that puzzle I was working on. I learned a new Greek verb form. The aorist isn’t as hard as advertised, compared to atevi grammar. I reviewed the latest race car design. Remember I had lunch with Gin and her staff last week, and we have that race in their hallway next week, Cajeiri’s team, namely us, against Gin’s engineers, with some of the crew betting on the outcome. I have to bet with my own staff. She has to bet with hers. I have second thoughts on the bet between us being in tea, of which Bindanda tells me I have one cannister remaining, and they are likely as short, by now. I think we should have kept it to sugar packets. We have more of those. Either of us losing will put us in truly desperate straits for caffeine. I think I should propose to Gin that we change the bet to sugar. And it’s the theory of a bet that matters, isn’t it?

Meanwhile Cajeiri’s birthday is coming on apace. He just this morning proposed we turn the birthday party into a slumber party—God knows where he learned that term, but I have my suspicions he’s seen one too many movies—and he’s insisting on inviting his young acquaintances from upstairs. Cenedi has informed him that propriety wouldn’t let Irene attend an all-night party with boys. Cajeiri absolutely insists on both Irene and Artur, and Gene, of course, and now he wants no chaperons at all. Atevi security is sensibly appalled…

He deleted that paragraph—not the first he’d set down and then, considering the reputation and future safety of the boy who someday would be aiji in Shejidan, erased from the record.

Too many movies, too much television, too much association with humans, the aiji-dowager said, and he by no means disagreed with that assessment of young Cajeiri’s social consciousness and opinions. But what could they do? He was a growing boy, undergoing this stultifying trip through folded space during two critical, formative years when youngsters should be asking questions and poking into everything at hand. And Cajeiri couldn’t. He couldn’t open doors at will, couldn’t explore everything he took into his head to do—he couldn’t breathe without the dowager’s bodyguards somewhere being aware of it. There were no other atevi children aboard. No one had considered that fact, Tabini-aiji having had the notion for his son to go on this voyage as an educational experience, as a way of making his heir acquainted with the new notions of space and distance and life in orbit. Argument to the contrary had not prevailed, and so what was there for a six-year-old’s active mind on their year-long voyage out to Reunion Station? What had they to entertain a six-year-old?

The collected works of humanity in the ship’s archive. Television. Movies. Books like Treasure Island, Dinosaurs! and Riders of the Purple Sage. The six-year-old had already become much too fluent in human language, and remained absolutely convinced dinosaurs were contemporaneous with human urban civilization, possibly even living on Mospheira, right across from the mainland. Hadn’t he seen the movies? How could one get a picture of dinosaurs, he pointed out, without cameras being there?

And then—then they had picked up their human passengers from the collapse of Reunion, 4043 passengers, to be exact, now 4078 going on 4149 in the enthusiasm of people no longer restricted and licensed to have a precise number of children. On the return leg, there were 638 children aboard, an ungodly number of them under a year of age, and seven of them of Cajeiri’s age, or thereabouts.

Children. Children let loose from a formerly regimented, restrictive environment. And just one deck below, a very lonely, very bored atevi youngster, heir to a continent-spanning power, who had rarely been restrained from his ambitions where they didn’t compromise the ship’s systems.

It was like holding magnets apart, these opposites of amazingly persistent and inventive attraction. Once they were aware of each other, they had to meet. The situation made everybody, atevi and human, more than anxious. Two sets of human parents had vehemently drawn their children back from all association with Cajeiri, fearing God knew what insubstantial harm. Or substantial harm, to be honest: Cajeiri, at seven years of age, had most of the height and strength of a grown human—he could hardly restrain the boy if he took a notion to rebel.

Cajeiri had hurt no one, physically. He was ever so careful with his fragile friends. He was not given to tantrums or temper outbursts, which, considering his parentage, was extremely remarkable restraint for a seven-year-old. He had, of the remaining five children, a small, close circle of human associates who dealt with him almost daily—a clutch of mostly awed human children who kept Cajeiri busy racing cars and playing space explorer and staying mostly out of trouble… if one discounted the fact that they had learned to slip about with considerable skill, using service doors and other facilities that were not off-limits in the atevi section of the ship.

That was one problem they had to cope with.

There was another, lately surfaced, but the first of all fears, namely that these young human associates told the boy things. Cautioned never to use the words love, or friendship, or aishi, or man’chi, and constantly admonished, particularly by the paidhi, they had found others he should have forbidden, had he halfway considered. Notably, the words birthday party. They had told him, and, worse, invited him to Artur’s twelfth, an occasion of supreme revelation to an atevi youngster.

Refreshments. Presents. Parties. Highly sugared revels.

Four months ago, Cajeiri had served notice he wanted his own birthday celebration, his eighth being the imminent one, and the one he looked forward to celebrating with his—no, one still did not say friends, that word of extreme ill omen between atevi and humans. His associates. His co-conspirators.

No, had been the first word from Cajeiri’s great-grandmother, early and firm: aside from all other considerations, the eighth was not an auspicious or fortunate year, in atevi tradition. The dowager refused, even cut Cajeiri off from his associates for a week, seeing trouble ahead. So Cajeiri’s determined little band had attempted to corrupt the ship’s communication system (Cajeiri’s clever trick with the computers) to contact one another in spite of the ban.

Break them up and they fought the harder to reach one another. Aishi. Association. No question of it. Be it human or be it atevi, a bond had formed, between Cajeiri and the particular four of that five who, inexperienced in the facts of human history, innocent of a war that had nearly devastated the atevi homeworld over interpersonal misinterpretations, secretly regarded Cajeiri as their friend, as he called them aishidi, that word which did not, emphatically not, mean friends—vocabulary which didn’t match up emotionally or behaviorally, a circumstance of thwarted expectations which had historically had a devastatingly bad outcome in human-atevi history.

And here it was, like the planet’s original sin, blossoming underfoot.

Dangerous passions. But how did one explain the hazard to a human child who was just learning what true friends were; or to an atevi boy who was trying to iron out what constituted trustable aishiin, that network of reliable alliances that would, in the case of a likely future ruler of the aishidi’tat, make all the difference between a long, peaceful rule or a series of assassinations and bloody retribution?

He wrote to Toby about their several-months-long problem, he confessed it to himself, because he had not the fortitude or the finesse to lay the whole situation out in detail for the boy’s father in that other letter. And then he inevitably erased the paragraphs he wrote, saying to himself that humans had no need to know that detail about the future aiji’s development—and saying, I should let the dowager explain the boy’s notions to Tabini.

But after the computer incident, which had incidentally locked all the doors on five-deck and caused a minor security crisis, even Ilisidi had thrown up her hands. And, instead of laying down the law, as everyone expected, the dowager had seemed to acquiesce to the birthday. Locked in her cabin and grown unsocial in the long tedium of folded space, she undoubtedly knew hour to hour and exactly to date what was going on with preparations for this eighth, infelicitous birthday, and she had said, on that topic, as late as a week ago, “Let him learn what he will learn. He came here for that. Best he see for himself the problems in this association.” And then she had added the most troubling information: “Puberty is coming. Then things will occur to him.”

That posed very uncomfortable notions, to a human who had long passed that mark and who had found his own intimate accommodation with an ateva of his own bodyguard—an understanding which they neither one acknowledged by what passed for daylight. Much as humans knew about atevi, and an earlier puberty in certain high-ranking individuals was one of those items, there were items the outrageous dowager might mention, but that even his most intimate associate would not feel comfortable discussing in pillow talk. Puberty, it seemed, was one of those unmentionables. It was, and it was not, the point at which feelings of man’chi, of association, firmly took hold of a developing ateva. It was intimate. It was embarrassing. The dowager, armored in years and power, would mention such things with wicked frankness. Jago, with whom he shared his nights, would rather not.

Well, damn, he thought, embarrassed himself, and on increasingly difficult ground. It was so embarrassing, in fact, that Jago had turned her shoulder to him and gone off to sleep. Which left him staring at the ceiling and wondering if he had offended her.

The explanation had left him with more questions than answers, and an impending birthday.

That topic, his staff would discuss. Had discussed, in detail. Atevi birthdays tended to be celebrated only if the numbers were fortunate, which worked out, with rare exceptions, as the paidhi well knew, to every other year. The infelicitous numbers, those divisible by infelicitous two, were questionable even to acknowledge in passing, except as properly compensated with ameliorating numbers. There might permissively be quiet acknowledgement in the case of a very young child—a sort of family dinner, for instance, had become traditional in the worldly-wise capital, elders felicitating the young person and admonishing him to good behavior, mentioning only his next, more fortunate year, and pointedly not mentioning the current one.

But, God help them, Cajeiri had seen Artur enjoy his birthday presents and being the center of festivities and adoration.

Was it awakening man’chi? Was it that inner need to be part of a group? If it was, it damned sure shouldn’t be satisfied by a human, however well-disposed.

We’re having the long-awaited birthday party for Cajeiri. This is, inescapably, an event involving the whole staff. There will be Cajeiri’s young guests, and I’ve given Bindanda recipes for authentic cake and ice cream, such as we can manage with synthetics and our own stores. We’re very careful about the ingredients, to be sure—no incidents, no alkaloids served to the human guests… no poisoning people’s children at a birthday party.

And this being, of course, an eighth birthday, we mustn’t mention it’s the eighth. You know what that means.

So there’s been ever such careful plotting on staff to figure how to do this gracefully. Narani suggested a beautiful patch on the situation, that we can celebrate not the oncoming eighth, but the felicity of the very fortunate seventh completely completed, so to say. And after that little dance around numerical infelicity, we have only to communicate to the parents of his human associates that they and their offspring must in no wise say ‘eighth birthday’ or ‘eight years old’, but rather say that he will be ‘completely seven.’ We seem to have finally persuaded the human parents that this semantical maneuvering is no joke. I tried to explain to the parents in that meeting yesterday, and they are the best of the best, who at least can conceptualize that passionate feelings other than human might exist in very non-human directions. Most of the Reunioners can’t remotely imagine such a case. Especially they can’t imagine it in folded space, where their brains aren’t quite up to par. Universally it’s a hard sell, in concept, to people who’ve always defined universal reality by their own feelings, and have never met anyone unlike themselves.

The humans they had rescued off Reunion Station were, to say the least, not acclimated to dealing with non-humans—they were incredibly provincial, for space-farers, and Artur’s mother had even called the to-do over the attachment between the children that very dangerous word, silly.

The woman had meant, certainly, to reassure him that she didn’t expect there would be any trouble. But that was precisely the point. She didn’t remotely grasp the history of the problem, or its potential outcome. Any Mospheiran, and he was Mospheiran, from the onworld island enclave of humans, found that mother’s attitude of laissez-faire both sinister and very scary. This was, he saw in that statement, a well-meaning human as naïve in atevi culture as Mospheirans had been before the Landing—before each side’s ignorance and each side’s confidence they were completely understanding one another had triggered the War of the Landing, the cataclysm that nearly ruined the planet.

Out of that conflict, the one good that had come was the paidhi’s office—a human appointed as the atevi aiji’s own translator and mediator where it regarded the mysterious thought processes of humans, the human appointed to execute the terms of the treaty that had ended the War, turning over human technology to the atevi conquerors at a pace that would not work such grievous harm on atevi culture. He understood his predecessors’ history, he knew what they’d been through, what they’d learned painfully and sometimes bloodily, over the elapsed centuries.

And trying to convey his Mospheiran-born experience to the Reunioners, it was like starting from the beginning—like being the first paidhi that had ever existed. Reunioners, born in space, entirely unaccustomed to accepting other languages and other human cultures, let alone non-human mental processes, had just come within a hair’s breadth of starting an inter-species war in the district where they had come from.

Which was why humans elsewhere had had to send Phoenix out to collect them and get them back to safety in the first place. Humans who lived with atevi had known the moment they heard of human encounters with neighboring aliens that they were possibly in deep trouble. And, oh, God, they had been in trouble—had all but provoked another species into wiping them out and hunting down the rest of humankind.

Had the Reunion refugees now learned from this experience? No. The majority of them chose not to regard the near-war as in any sense their fault, were quite indignant at any such suggestion, and had no ingrained appreciation what a serious business it was to trample on other species’ sensitivities. Certainly they had not a care in their world that their Mospheiran cousins had, some hundreds of years in the past, fought a great war over such ‘silliness’ as humans insisting on fixed property lines and disregarding the fingernails-on-chalkboard effect of human numerical deafness, in their children’s considerate attempts to learn the atevi language.

Infelicitous eighth?

The fact was, as every Mospheiran knew, and Reunion folk did not, atevi heard numbers in everything. Numerical sensitivity was embedded in the atevi language, very possibly even in their brain architecture, influencing their whole outlook on the universe. Bjorn, Irene, Artur and Gene, who had made rudimentary efforts at talking to Cajeiri in his own language, had seemingly grasped the facts of the situation faster than their parents, though their own human nerves were absolutely deaf to the mistakes that made atevi shudder: they were continually trying to figure out what made Cajeiri scowl at them as if he’d been insulted, and to add to the problem, they were not particularly good in math, which was so matter of course to Cajeiri he had trouble understanding their mistakes. Their back-and-forth computer correspondence, which protective atevi staff had hacked, were full of very long, very convolute explanations to each other as to what one had meant by “two of us,” and, apologetically, how two wasn’t really “two.”

The youngsters’ willingness to analyze their communication was at least encouraging, no matter that they were surely not destined for a career in mathematics and would never progress beyond the children’s version of the language. Their being drawn to Cajeiri—in a bond that, for reasons he himself could not completely understand, atevi were reluctant to sever—was fraught with every imaginable difficulty.

But if they could somehow keep an even keel under the relationship, and avoid an emotional breach, who knew? The next generation necessarily extended into a scary dimension of time the paidhi couldn’t control, couldn’t even imagine, let alone predict. He only saw, uneasily, that the very circumstance of there being four young humans had seemingly undermined atevi resistance to the idea of their association: he knew that four was calamity unless combined with an apex fifth, a dominant fifth. These four under the peculiar circumstances of this voyage, constituted some kind of foreboding threat in certain minds. Joined to an atevi future ruler—they made a five of potential power—at least by what he could figure Ilisidi’s reasoning to be.

Scary as hell, to a human trying to figure out a volatile situation that might undermine everything he’d struggled to preserve.

But today all he had to cope with was the debated slumber party, in which Cajeiri had not even remotely twigged to the impropriety of young people of various sexes spending the night in the same bed. Irene, Cajeiri said, wasn’t a girl, she was Artur’s sister. Translation: she was clan, she was family, she was part of his aishid. Which had to worry anyone in the context of oncoming changes in the boy.

Not to mention the understanding of human parents, who saw a boy as tall as a grown human proposing to sleep with their very underage daughter.

Three ticks of the keys windowed up an ebony face, a young face, though humans not used to atevi might not see how young… gold eyes that brimmed with questions, questions, questions. There was so much good in that young heart. So much enthusiasm and willingness.

And his parents’ good looks, and his father’s cunning and, when thwarted, his father’s volatile temper. Which, fortunately, there was the aiji-dowager, his great-grandmother, to sit on, when needed.

Tantrums there might be, a last-ditch insistence on the slumber party.

We decided to offer a movie for the entertainment, he calmly wrote to Toby. Since we haven’t encouraged the boy in his movie-viewing out of the Archive lately, and since the dowager has loaded him with homework to fill his time, this should be a special treat.

In several well-considered opinions, Cajeiri had gotten far too fond of those human-made movies. Prepubescent as the lad still was, most machimi plays, the classic and common literature of his own people, did sail right over his head, both intellectually and emotionally, and unfortunately that had combined with the boredom of a long voyage to make the human Archive all too attractive to a boy who should have been out riding the hills and conniving with other children—not that Cajeiri understood the nuances of the human dramas, either, but there was in the vast Archive a great store of the sort of movies he favored… notably those with abundant pyrotechnics, a great deal of sword-swinging, and most especially horses and dinosaurs.

Machimi were, in origin, stage-plays, largely filled with people talking, in limited, static sets. The classic ones didn’t have the flash and sweep of a movie epic. So what did their boy do when admonished to view the classics of his own culture? He fast-forwarded to the blood and thunder scenes, and disrespectfully skipped through the intellectual and sensitive parts, ignoring all the things that should have begun to mean something to his developing brain.

This fast-forwarding button had begun to make his elders just a little uneasy. He was bright. He was extremely bright. They were not sure about his other attributes, or how this fascination with blood and battle played in his developing brain.

Horses, pirates, and especially dinosaurs are his current passion, he wrote to Toby. Did I mention he’s keenly disappointed to be told we don’t really have horses or dinosaurs on Mospheira? He was all ready to take a rowboat over there and see them, and we had to tell him they were long ago and far away, and that dinosaurs were not alive when humans appeared on old Earth.

Cajeiri had put in his request for Captain Blood as the birthday movie, but the dowager’s staff had lately made the firm decision that pirates were not appropriate fare for a young one-day ruler. Cajeiri and his young associates had recently sent each other a series of fanciful between-decks letters about overthrowing the ship-aijiin and cruising the universe as space pirates, a plan which, whatever its lack of feasibility, entirely scandalized his grandmother.

The offering the staff has settled on for the festive occasion is the lost world, which has wall-to-wall dinosaurs. Presumably this will please him, since we’re sure this is a version he has not seen and the dinosaurs, staff informs me, are particularly well done.

Surely in the next few years the problem would fade: his great-grandmother seemed to think so. When the boy got old enough, the machimi plays, the ancestral art of his Ragi forebears, would touch his awakening sensibilities and adult instincts in ways peculiarly and exquisitely atevi. Then human-made movies would no longer satisfy the young rascal.