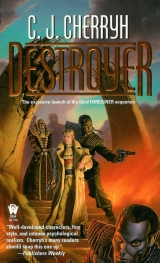

Текст книги "Destroyer "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

That chanced, unaccountably, to amuse the old lord. “So have we all, paidhi-aiji. And we are all still here.”

“And Murini’s predecessor is not,” Ilisidi observed dryly. “But Murini, alas, is no improvement. Some work must be done until we have gotten it right. So! We are entirely surfeited with tea, Tati-ji. We shall go to the solarium. We have always esteemed your solarium.”

“An honor.” The scowl persisted. “Do make free of it at your leisure, Sidi-ji. We, meanwhile, have detailed instructions to give, to permit this doubtless useless message to go through. We shall lower defenses in the west, altogether, to have no possible misunderstandings. We shall instruct the gatekeepers to let this message pass and let in any Taibeni that arrive, there or at the hunting-gate. Nand’ paidhi, if you will brief your own people and ask them to consult, to join a meeting of all our staffs—except these damned Taibeni teenagers, who will be told what they need when they need it, hear? I shall send three of my men with them, to see them pass the gate and get to the limit of our province. Immediately.”

“Immediately, nandi.” Bren rose, understanding a dismissal, and bowed. “With utmost attention.”

He left. He gathered Banichi and Jago to him outside. Of Cajeiri or his young followers there was no sign.

“The heir has written a letter to Taiben, nadiin-ji,” he said to them as they climbed the stairs.

“Antaro expressed her great desire to be the one to carry it, nandi,” Jago said in a low voice.

“There might be Kadigidi out, even in that direction,” he said. “Lord Tatiseigi says he will advise his security to let her pass, but we can by no means guarantee what else is out there that she might meet, the worse as hours pass.”

“We did soberly caution her, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “And we advised going overland, by mechieti.”

“The young gentleman is deeply concerned,” Jago said, “and expressed a wish to send Jegari with her, but Antaro said he should not go. Jegari will likely not leave the young gentleman.”

Will not, would not. Emotional decisions, man’chi, newly-attached young instincts at war with basic common sense, none of them Guild, none of them with adult comprehension of what they were up against, and Ilisidi encouraging this move, all because he had said one critical word: Taiben.

“They are attempting too much, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “Tano and Algini took these youngsters in hand last evening for brief instruction, but that only concerned house security. Jago requested the house staff give the girl a firearm: there is considerable resistance to this request.”

“The lord has ordered thorough cooperation.” They were in the upper hall. “Go back, Jago-ji, and inform them of that. She should have a gun, if she knows how to use it.”

“Yes,” Jago said, and dived back down the stairs, pigtail flying.

He was far from happy with the arrangement—with consulting the Taibeni, yes, that was a possibility with some value, if Ilisidi had sent Nawari. But he did not agree with sending a teenaged kid through a potential ambush, however remote from the expected line of combat, even if Tatiseigi had relented and sent an escort. He least of all agreed with the pressure the dowager had put on the boy, newly possessed of—

Damn it, friends was not the appropriate concept. But whatever it was, the boy had just picked up longed-for companionship in a damned lonely world, a satisfaction of atevi instincts they had worried would never wake, and now Ilisidi used him and the two Taibeni youngsters without detectible compassion. Twice damn it. And damn the whole situation. He might have succeeded in diverting Cenedi from his notion of a hopeless foray into Kadigidi territory by making that suggestion of his, but it could be at terrible cost.

And now what did he do? He and his guard were committed to stay here—he couldn’t pull his staff out of the defense of Tirnamardi after he’d backed this alternative plan to stop Cenedi from what his staff called a mistake. He couldn’t urge the Taibeni to come in here, where they historically weren’t welcome, and not be here to meet them, to iron out any misunderstandings. And he couldn’t have sent an appeal to the Guild, asking permission to appear before them and then vanish into the hills, unfindable if things went wrong, or if that Guild safe-conduct turned up.

And he couldn’t now take Cajeiri out of here, and pursue the chance of finding his father, not when Cajeiri was the principle reason the Taibeni might consent to come in to defend their historic adversary.

Jago rejoined them before they reached his door. “The Atageini staff agrees,” she said, “and has gotten their lord’s word on it. They will instruct her such as they can, providing both communications and a sidearm, and escorting her as far as the edge of the Taiben woods.”

Much better. Damned much better, and Tatiseigi had come to his senses, not hampering any chance of success. Bren let go a deep breath. There was a chance they would survive this.

“Good,” he said as Banichi opened the door and let them in. Tano and Algini were waiting inside, on their feet.

“We are staying here, nadiin-ji,” Jago said. “One believes it may be an interesting night ahead of us. The Atageini have requested Cajeiri send Antaro-nadi to Taiben, to bring reinforcement.”

Eyebrows lifted. That was all. But Banichi said soberly, “Measures will be taken all about the grounds, once the girl has cleared the perimeter. Likely we will see eastern defenses activated in very short order, if they are not now. But the Kadigidi will expect that, and go around, if they are not already in the province. House defenses are generally adequate on the first floor, Bren-ji, far less so on the upper floors. There exist some few very modern surprises. And we do not know if the house staff has told Cenedi all its secrets, either of deficiencies or of capabilities. Soft target, hard target. One earnestly begs you recall your precautions at all points, particularly if there is an alarm, Bren-ji.”

Wires. Nasty devices that could slice a foot off. Electronic barriers. He hadn’t had to live with such hazards since the worst days in the Bu-javid, and coping with them now meant setting a series of checkpoints and alarms in his head, not to cross narrow places without extreme precaution, not to leave his bodyguard for an instant and never to precede them through a door, insert a key in a lock, or expose his head in a window.

And soft-target/hard-target. Which meant the upstairs was certainly not where they wanted to be tonight. The upstairs was where an attack was meant to enter—and descend at disadvantage, into much more modern devices, and defenders ready and waiting, likely in the dark. Soft-target, hard-target was a fairly transparent mode of defense, but one still hard to deal with, even if the enemy had reliable spies to inform them, because the line at which the defense would go from soft to hard was not going to be apparent and might change quickly.

Antiquated equipment, but maybe the sort to lull an attacker into thinking it was all going to be easy. He didn’t utterly trust Tatiseigi to tell them everything.

But he didn’t look forward to tonight at all. He didn’t look forward to the rest of the day, which held a diminishing few hours of tedium and tension before twilight brought a rising likelihood of trouble. He had drunk tea enough to float, and his nerves were jangled—always were, after one of those breakneck logical downhills with Ilisidi, not to mention Tatiseigi in the mix.

Not to mention, either, a human urge to go down the hall and offer the poor kid some sort of reassurance or at least moral support, considering an order far too hard for children. Damn the situation. Damn the Kadigidi. He passionately hated gunfire. It always meant someone like him hadn’t done his job. And there was far too much evidence of that all around him.

His staff settled down near the fireplace for some quick close consultation of their own, and he found there was one thing constructive he could do in that regard. He unfolded his computer and produced a detailed map of the terrain. He had no way, in the upstairs of this traditional and kabiu household, to print it out for them, but they clustered around him, viewing the situation down to the hummocks and small streams. There was a discussion of the stables, where their riding gear was stowed, which Tano had checked and located—it was the pile of stable sweepings, curiously enough, which had told Tano the story of recent visitations: one lived and learned. They discussed the dowager’s rooms, which Jago had observed were similar in layout to their own, and they even considered the topiary hedges, where devices or automatic traps might be located, if such sensors had survived the mechieti’s foraging.

“There will be electronic sweeps,” Banichi said, and pointed to a stream that ran from the Kadigidi heights down toward Kadigidi territory. “That low spot, Bren-ji, is as good as a highway for intruders, except one can be reasonably certain the Atageini will have detection installed there and at other such places. And the Kadigidi will know it. So there should be devices set at other alternatives. We could not pry details out of this staff. Unfortunately, we are far less sure the Kadigidi have not done so.”

He had not considered such things in years. He studied the map, tried to recall how the pitch of the land had seemed as they had ridden in during the rain—a deceptive pitch. He remembered how cleverly the rolling hills concealed things one would never have expected—the whole length of the fence and the perimeter had vanished at certain times—which meant attackers might likewise be below electronic sweeps, moving as they pleased. His staff pointed out the probable course of a large, late incursion from the Kadigidi, and then the route the Kadigidi were likeliest to use because that first one was too probable.

A knock came at the door. The household staff came to beg his staff’s attendance at a general meeting. Jago opted to be the one to stay with him and stand watch.

They went on calling up maps, he and Jago, Jago taking mental notes, absorbing what might be useful to the team tonight. The meeting elsewhere went on a considerable time, more than an hour, until finally Banichi, Tano, and Algini came back, very sober of countenance.

“One has asked the staff quite bluntly, nandi, about the activity at the stables,” Tano said. “They maintain they shifted the lord’s herd in eight days ago for a seasonal hunt and out again, in favor of a small group used for ordinary purposes, and that this was all done by staff. One detected no lie, and this activity predated any action the Kadigidi may have taken against us. The lord generally keeps only seven mechieti here against personal need. That also agrees what what I saw.”

An autumn hunt. Plausible. Plausible, because one did not move part of an established mechieti herd out of its territory—or one had the remnant trying to join the others cross-country and tearing up fences and crops in the process. Even if it had been a small hunt, the lord would have brought an established herd in for the use of his guests, and then moved back a small herd, following the hunt. One did not believe Lord Tatiseigi himself still rode. But his staff would. Out of such events came the meat for table, the meat for market, meat for all the people of the province, the cull of game before the coming winter. Hunters from every Atageini village and town would have participated.

“They may or may not have been completely forthcoming about the deficiencies or the strength of the defenses,” Banichi said. “They had already activated the southeastern perimeter defenses last night, when we arrived.” That would be, precisely, the Kadigidi boundary. “They say there had been nuisance activity, spies, that sort of thing—likely because of the ship in the heavens. The Atageini raised defenses on the others today, repaired the one we blew, and have privately called on the various town-aijiin to take other precautions, asking them to avoid conflict with outsiders and to avoid the boundaries, the usual sort of thing. The Taibeni girl left some time ago, with two men in escort. She will likely have passed the gates by now.”

Things were moving.

Moving in the hall, too. Footsteps passed their door at a high rate of speed, drawing a look from his staff.

Jago got up and went to stand near the door, not opening it, but listening. She shot back an anxious look.

“There is some little disturbance,” she said, from that auditory vantage, and her hand was on her sidearm, unconsciously or not. She made the hand sign for man, and run.

The staff got up from their chairs. Bren shut his computer, rising, listening, his heart beating a little faster. The dowager’s rooms were in the direction toward which those steps had run. The boy’s were in the direction from which they had come. But the steps were heavy, a man’s.

Second set of hand-signals, Banichi to Jago, and she unlocked the door, opened it a crack, then looked out, and went outside.

Banichi followed, hand on his sidearm, not quite going so far as to draw a weapon in an allied house, but a heartbeat away from that move. The door stayed ajar. Bren stood still, not retreating as he ought to the neighboring room, but again, it was an allied house, in which they had basic confidence. Tano and Algini were on either side of him, Tano a little to the fore, protective position relative to the door. They signalled a move out of line with the window. Algini moved instantly to check that, and evidently saw nothing alarming.

More running steps, these audible. Jago, Bren thought, headed for the stairs. He stood still, then remembered his gun and went and retrieved it, still within Tano’s protective screen. He slipped it into his pocket, along with an extra clip.

Jago came back, running, and came inside. Banichi headed down the hall in the direction from which the first runner had come.

“Nandi,” she said. “Cajeiri is not in his apartment. The window is open, the alarm is disabled, and no one is in the apartment.”

“Damn.” The thought was instant and ominous.

Tano and Algini headed for the door, going out the way Banichi had gone, doubtless to have a firsthand look for how and why.

But it was foreseeable. They’d gone, they’d gotten out of the house. Banichi reported Antaro had left on her mission, and now the boy and Jegari had vanished? Enemy action?

No. They were all three of them going, fortunate three, sticking together, while the house staff had been in a meeting and nobody had been expecting it—a human could at least hope that was the case, and not that some Kadigidi assassin had gotten in.

“The outlying defenses are still down,” Bren recalled. Had not this boy grown up on human novels, human stories, human notions of heroes and desperate adventures? “I know exactly what they have done, Jago-ji. They have gone with Antaro. We should check the stables.”

Jago’s brows lifted. She exited to the hall, and was gone for a moment.

An interminable moment. He shed his formal coat, hung it on a chair and picked the warmer, bulkier short jacket out of his baggage. He transferred the handgun and the clip, took his pocket com, a knife, and his pill bottle, then stuffed them into a zipped pocket, lace shirt warring with bulky, resistant jacket. He half fastened it, from the waist.

Jago came back.

“They have taken mechieti,” Jago reported, and by now Banichi and Tano and Algini had come in. “Nand’ Cajeiri and Jegari have taken mechieti, and the house has made a dangerous amount of inquiry on its antiquated com system. Bren-ji, what are you doing?”

“Going after them, nadiin-ji.”

“By no means!”

“To appeal to Taiben was my idea, nadiin. It was my suggestion in passing that provided the notion, and the dowager forced the boy to write the letter himself.” Personal distress overset coherent arguments, but in his mind, certain things had leapt up in crystal clarity, a boy’s sense of honor, a new-made obligation, a shiny new man’chi, and a detestable letter he had been forced to write. “This job I can possibly do, since negotiations with the Kadigidi are highly unlikely tonight. The boy knows me; the Taibeni know me, if we have to chase them that far.”

“They know us as well,” Banichi said, clearly about to propose the paidhi stay put and his staff take the trip in his stead.

“And if they take you for Atageini staff riding across that line after them, there is every likelihood of misunderstanding, and of utter disaster if they take you for Kadigidi. Me, there is no mistaking, and the boys will less likely run from me. Go say so to the house staff. Say it to Cenedi. Get us mechieti to overtake them.” A car might have a certain advantage getting to the gate if there was one available that could go above a walking pace, but not on the estate’s winding roads and certainly not overland, and least of all that ornate antique Lord Tatiseigi had used to meet them. The youngsters had had a long head start, and might well go overland. “Quickly, nadiin!”

He rarely ordered details of a security response. His staff habitually made all the operational decisions. But this was not a defensive situation, even Banichi knew it, and they took orders and left in haste, all but Jago, who stayed for his protection and made his staff’s preparations, lightweight for her Guild, but involving plenty of ammunition, long and short, two rifles, a handful of other ring-clipped small bags, not a light load for any two humans.

“The computer,” he recalled in alarm, and went and flung it open, dithered over the keys until he had it up, and input a personal code, then shut down and shoved it and Shawn’s unit into the back of the linen closet, breathless with haste. “I have put it under lock, Jago. I’ll tell you the code once we go outside. It will be safer left here, hidden. One fears it will be people that the Kadigidi will be looking for.”

“Yes,” she said brusquely, in working-mode, no nonsense and no courtesies. She held the door for him and they both exited into the hall.

So, it developed, had Ilisidi exited her rooms, between them and the stairs. Ilisidi was standing in the hall near the steps, appearing in no mood to trifle, and house staff was attempting explanations.

“Damned fools!” she shouted, or approximately that. “Nand’ paidhi?”

“Aiji-ma, one hears the window alarm was disconnected. One supposes the young gentleman has undertaken the mission himself. I shall find him. Atageini might be shot trying it.”

“So might he, the young idiot. We have emphasized that the western defenses must be let down for him no matter what happens here, which one trusts this household has the basic skills to accomplish. We have asked for an accounting of every person in this household, and we intend to have it! We only hope he has gone by his own will! Why are you standing there, nandi?”

“Aiji-ma.” He hurried for the stairs, Jago right with him, hastened down them, and met Cenedi on his way up. “Cenedi-ji, we are going after the boy ourselves, at all speed. Can the gatekeeper possibly be queried and advised to prevent them without betraying the nature of the problem?”

One rarely saw Cenedi so distressed—not since the boy had pulled his cursed tricks on the ship. A houseful of Guild on high alert—but occupied in general conference—and the boy, who had heard all the complaints about lax security, had gotten out of his quarters and followed Antaro. One hoped that was the whole story.

“The window was open, nadi-ji,” Jago said to Cenedi. “The window contact was pried loose inside and stuck against its receiver, this while the system was armed. We are headed for the stables. The young gentleman and his companion have taken mechieti.”

“Clever lad,” Cenedi said, tightlipped. “Nandi.” And with that parting courtesy and fire in his eye Cenedi went up to inform the dowager of whatever detail of the situation he had been going to report. Some of Ilisidi’s young men were with her in the upstairs—one could hear Cenedi deliver instructions, sending his own men to manage a discreet phone call to the gate, and to check windows up and down the hall. By the time they reached the downstairs Lord Tatiseigi himself was out of his study in a cluster of his own men, looking entirely discommoded.

“Our precautions are adequate,” Tatiseigi shouted at the commotion above, “unless sabotaged!”

Bren wanted no part of that dispute. He headed out through the lily foyer, out the front doors of the house, with Jago, and found Tano headed up the broad steps.

“The boys told the grooms that the dowager had sent them with a further message,” Tano said. “They took the last two of lord Tatiseigi’s mechieti and rode out to overtake the girl.”

“The scoundrels,” Bren muttered, heading down the steps.

“Come, Tano-ji,” Jago said, “all of us are going.” Tano, whom Banichi might have sent back to watch the gear, changed course and immediately headed down the steps again, overtaking them on the cobbled drive and taking part of the load of ammunition and one of the rifles as they walked.

The path to the stables lay at the side of the house, beyond a well-trimmed, doubtless security-rife hedge, devices that would not likely have been activated, not with household staff coming and going to the stables on emergency missions.

Clever, damnable young scoundrels. Lying was not Cajeiri’s usual recourse, but it was within his arsenal. It was in those novels he had been reading and those entertainments he had been viewing on the ship.

At least—at least, Bren said to himself, the boys were only loyal and stupid, not kidnapped.

Breathlessly, down the well-trimmed path to the stables. Mechieti were complaining. Loudly. Banichi, Algini and the grooms were in the process of saddling up.

“You should not go, Bren-ji,” Banichi said, heaving on a girth. “Our numbers are more fortunate without you.”

Seven without and eight and ten with, counting the expected recovery of three fugitives and two Atageini escorts.

“But less fortunate numbers toward finding them in the first place,” Bren shot back. Two could do that kind of math, and his staff was by no means superstitious. “The defenses are confirmed down in the west, Banichi-ji.”

Jago muttered: “One doubts the boy will join the escort. He will follow them. And we know what tale he will tell the gatekeeper.”

“Someone is calling the gate to forestall that.” But not someone with knowledge of how the boys had gotten the mechieti. “Go advise them the boy is using the dowager’s name, ‘Gini-ji. Run.”

“Yes,” Algini said, and sprinted.

“They took the two remaining of the local herd.” Banichi said, “prize stock, and were gone at high speed.”

“One assumes you will take our own herd leader.”

“I intend to,” Banichi said. Another saddle had gone on, the last. “Up, Bren-ji.”

Bren accepted the boost up, took up the quirt, kept quiet, under the overhang of the stable roof. Banichi accepted a rifle and an ammunition kit from Jago, slung it over his shoulder and mounted up. The rest of them did.

“We offer apologies,” the head groom said, “profound apologies for this sorry affair, nandi.”

“You were lied to, nadiin,” Bren said, as good a grace as he could muster, and the stable revolved in his vision as Banichi took the leader out and the mechieti under him followed as if on an invisible lead.

The rest of them had mounted up, and moved out, Algini’s moving with them. Behind them, wood splintered. A barrier shattered.

“Damn,” Bren said, looking over his shoulder.

“We have mistaken one of our matriarchs,” Tano said. And no question, in unfamiliarity with the herd, they had not recognized the mechieti in question, ranking matriarch. The gate was broken and the mechieti that had broken it surged past the grooms with a rip of her dangerous head. The grooms scrambled back. Three more mechieti, exiting behind the other, took out a porch-post on their way to daylight, and with a thunder and a squeal of nails and wood, the porch sagged. The whole unsaddled herd broke out, following them along the path to the cobbled drive.

Algini met them on the drive, at the bottom, hard-breathing. “They passed the gate, nandi. But not the boys. Two loose mechieti showed up with the party before they reached the gate, saddled, and joined the others. The boys have taken off afoot, likely to scale the fence.”

Oh, two years of conning ship’s personnel, building little electric cars and playing hob with ship’s security had created a boy far, far too clever for his own good. It was not the Taibeni teenagers that had accomplished this entire escape. He had no such notion. It was an eight-year-old Ragi prince with far too much confidence in his own cleverness, a deft touch with electrical gadgets he had gained from building toy cars with Mospheiran engineers and Guild Assassins, and a way of assuming such conviction, such lordly force, that he often got past adults’ wiser instincts. Not to mention other things he had gained from Guild company: speed to get near the gate, and never rely on the same trick twice.

Algini mounted up, the whole herd in motion. They rode clear of the despised cobbles, the mechieti stepping on eggshells all the way. On the first edge of the roadway Banichi took out at a loping run, not a comfortable pace, not something they had done in a long while, and Bren took a moment to find his balance, already finding the saddle a renewed misery.

Too late already, too damned late to prevent a commotion. The defenses were down, the boys had had better than an hour to be across the fence, and, damn it all, the escort would be riding along beyond the estate fence with two extra mechieti they could by no means drive off—instinct would not allow it; and with two boys hellbent on overtaking them.

“Nadiin,” the young scoundrel would say to them when they met, his golden eyes clear and as pure as glass, “the dowager my great-grandmother has added a message, which we are to carry ourselves.”

And what could two Atageini say to the contrary?

“Maybe,” Bren said to his companions, foreknowing if there was any good hope someone would have seen to it, “maybe the gate can call ahead to the escort and have them bring the boys back.”

“Not optimum, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “These cursed units of theirs make every transmission a risk. And that is not information to spread abroad.”

Tatiseigi was known to be as tight-fisted about technology as he was liberal with artists, conservative, reputedly not replacing the house gas lights with electricity until, oh, about ten years ago. But—good God, to short his security…

If the Kadigidi had monitored the house transmissions, everyone listening might get the idea that young gentlemen were roaming about the neighborhood virtually unprotected.

And would not the Kadigidi already be bending every effort to get there, while, thanks to the breakout, they had every last mechieti in the stable following after the young rascal, so that Cenedi and the dowager had no recourse but stay and defend the house, or escape in Lord Tatiseigi’s antiquated motorcar.

The girl’s escort would not necessarily suspect the boys of lying to them. Prudence dictated they not load the airwaves with inquiries to confirm the story. The boys would simply get their mounts back, with only moderately suspicious looks from Tatiseigi’s men—“We got down to fix a girth and they ran from us, nadiin… we knew they would go to you. We ran to catch up.”

Such a common mishap: mechieti with two of their number having disappeared over the horizon were inclined to present a problem in control, once they got the scent on the trail, and only two very foolish boys would both get down out of the saddle at the same time.

Those boys were now, at all good odds, themselves on their way to Taiben with Antaro… and if that were all the trouble they were facing at this point, Bren said to himself, he would cease his pursuit and let the youngsters reach the Taibeni, and, granted the Taibeni’s better sense, believe they would stay there.

But given all the fuss on the com system had made it likely Kadigidi had wind of confusion on the northwestern side of Atageini land, he could not leave it at that. The Taibeni, on their side, would not have a clue to what was happening, and two Atageini guards, while reasonably cautious, might not have any apprehension what a commotion had arisen around their mission.

Not good, Bren said to himself. It was not at all good.

Chapter 12

Bren held on, clamped the leading leg against the saddle and kept a grip on the leather. Any random glance back showed the whole damned mechieti herd crowding the narrow roadway, shoving against the low hedges, outright trampling them down as they went, where slight gaps in the shrubbery made spreading out attractive. Banichi stayed in the lead, and Banichi delayed for no second thoughts—in the hope—Bren nursed it, too—that Antaro and her escort would ride at a saner pace, perhaps stopping to talk at the gate, perhaps stopping to talk or argue where they met the boys—not long, but every moment gave them a chance.

The gate and the tall outer fence appeared as they crested a particular hill. The gatekeeper left his little weather-shelter amongst the vines and, clearly forewarned, opened the gates for them, to let them straight on through.

Banichi reined in, however, and all the other mechieti halted, blowing and snorting, jammed up close.

“Nadi,” Banichi said. “If the girl’s escort comes back and we do not, send them back out to us. We may need help out there. We fear the Kadigidi may be on to the messenger.”

“Nadi,” the man said—not, perhaps, the same watcher they had antagonized the night before—“nadi, one had no prior advisement there was any possible difficulty—”

“Indeed,” Bren said. “We know. They took the extra mechieti with them?”

“Yes, nandi. They said the strays had overtaken them, and they were puzzled. I had no means to keep them, and one feared they would stray along inside the fence, if… ”