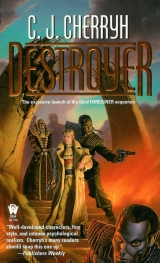

Текст книги "Destroyer "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Now it sounded as if the station, recently recovered, after centuries in mothballs, had gone back into full-scale mining operations, by robot, the way they should have done. The station must be needing the grosser supplies in their ship-building now—a project which would need far more supplies than they could lift from the planet’s surface. Electronics, rarer metals, some ceramics: those would still come up the long, expensive climb out of atmosphere, but apparently they’d reached the stage where they needed to haul in iron and nickel from the floating junk that was so abundant up here. That meant they’d gotten the refining process out of mothballs and gotten it working.

Well. Good. Counting a kyo visitation was not beyond probability, that progress toward a second starship was very good, and they’d happily contribute the mining bots they had stowed in Phoenix’s forward hold. It was a good thing to look as powerful and prosperous as they could. Ogun had put them ahead of schedule.

“Clear under caution,” the announcement went out, generally, and Kaplan listened to the unit in his ear for a second. “You’re clear to move now, sir, but get to seats fast and don’t get up.”

“We may sit,” Bren translated that, “and should move quickly to reach our seats and belt in.” The dowager and Cajeiri were nearest the seats in question, those along a section of freestanding wall—actually an acceleration buffer—at the rear of the bridge. The dowager moved with fair dispatch, taking Cajeiri with her, Cenedi and his man in close company with them and seeing them settled. “Go,” Bren said to Gin, after the dowager was in, and Gin and Jerry moved out.

He came last with Banichi and Jago, and slipped quickly into a seat. In front of them, row on row of consoles and operators tracked surrounding space, the condition of the ship, the location of various items like the stray mining bots—and, one presumed, established communication with the station.

Above it all, a wide screen showed a disk-shaped light, which was—God, was it really home? Was that beautiful star in center screen their own planet shining in the sun?

There, it must be. That dimmer light was the moon. And a bright oblong light that might not be a star. It might be the station itself. He wondered how great a magnification that was.

Bren found himself shivering. He suddenly wanted to be there faster, faster, as fast as at all possible, to see and do all he’d been waiting so long for. And to find out that things were all right, and that all the people he wanted to find were waiting for him.

Jase and Sabin, at the far side of the bridge, were close to another bulkhead and another shelter like the one they had left, but once they began moving about in some confidence, Bren stood up judiciously, hand on a recessed takehold on the curtain wall, and caught Jase’s eye.

Jase worked his way down the aisle in their direction.

“Sorry about that little surprise,” Jase said. “Is everyone all right?”

“We seem to be,” Bren said, finding himself a little shaky in this resumption of normalcy. “Was that just one of those things that sometimes happens?”

“I have no idea,” Jase said. “We’ve never been where traffic was an issue, not since this ship left old Earth, far as I know. Sabin doesn’t say a thing, but we’ve counted quite an amazing lot of these little craft. Sabin’s called the station, and if the chronometer’s right, it’s Ogun’s offshift. They’re going to have to get him out of bed.”

“I don’t think he’ll mind,” Bren said.

“Not likely he will.” Deep sigh. “Time lag is a pain.”

“Can you make out the shipyard? Have you been able to find it?”

“That’s the worrisome thing. There’s no activity out there. No lights, nothing. Black as deep space.”

A foreboding little chill crept down Bren’s back. A lot of robot miners. And no activity in the region that should be the focus of the effort. “That’s odd.” He saw a reply counter running on that image at the front of the bridge, down in the corner of the screen, now that he looked for it. It was -00: 04: 22 going on 23.

Four minutes without an answer. That gave a little clue about distance and magnification.

Then:

“Put it on general intercom, all crew areas, Cl.” That was Sabin.

“…. just got here,” came over the general address.

Ogun’s voice. Thank God.

“Can you respond?”

“Earth had one moon.” That wasn’t conversational on Sabin’s part.

“Mars had two,” from Ogun. Clearly an exchange of codewords. “You’re a welcome sight. How did it go?”

“Rescue was entirely successful. We have 4078 passengers.”

A little silence, a slight lagtime for the signal, but nothing significant. “What is your situation with the atevi on board?”

“Excellent,” Sabin said. “And they’re hearing you, at the moment.”

“Is the dowager in good health? Is the aiji’s heir safe?”

Right from human and ordinary, hello, good to see you, to how is the dowager? Odd swerve in topics. Bren’s pulse picked up, and he tried not to lose a word or nuance of what he might have to translate for the dowager.

“Both are here on the bridge, safe and sound. Why, Jules?”

Why in hell, Bren wondered simultaneously, are atevi the first issue?

“And Mr. Cameron? Is he with you?”

“Here and able to respond if you have a question for him. Is there a problem, Jules?”

“Just checking.”

“Checking, hell! What’s going on over there, Jules? Is there a problem on your side?

“Did you find anything out there?”

Bren found his palms sweating. Sabin shifted her stance, leaned close to the communications console, both hands on the counter. And became uncharacteristically patient.

“Peaceful contact with a species called the kyo, a complex situation. They’ve been willing to talk, thanks to the atevi’s good offices. Colonists are safe and rescued. We’ve got a lot to report. But I want answers. What is your situation, Jules? What’s this set of questions? Where’s a simple glad to see you?”

“We are immensely glad to see you .The tanks aren’t finished. The ship isn’t finished. Food is not in great supply here.”

Worse and worse.

“Jules, why not?”

“We have an ongoing problem. Shuttles aren’t flying. Haven’t, for eight months. We’re cut off from supply, trying to finish and fill the food production tanks on a priority basis.”

Banichi had gotten to his feet. So had Jago, Cenedi, the dowager, and, necessarily, Cajeiri, followed by Gin and Jerry.

Bren gave them a sign, wait, wait.

“Why not?” Sabin asked. “Come out with it, Jules. What’s happened there?”

“The government’s collapsed on the mainland. The aiji is no longer communicating with us or anybody. The dish at Mogari-nai is not transmitting. Shuttles are no longer launching from the spaceports. As best the Island can figure, the aishidi’tat is in complete turmoil and only regional governments are functioning with any efficiency at all.”

God.

“What is this?” Ilisidi demanded outright, and Bren turned quietly to translate.

“With great regret, one apprehends there has been upheaval in the aishidi’tat as of eight months ago, aiji-ma. Your grandson is not answering queries, Mogari-nai has shut down, and shuttles are not reaching the station with supplies, aiji-ma. The station is very short of food and rushing desperately to build independent food production facilities. Ogun-aiji is extremely glad to know you and the heir are safe.”

A moment of silence. Then, bang! went the cane on the deck.

“Where is Lord Geigi?”

Geigi, in charge of the atevi contingent on the station. There was a question. “I shall attempt to establish contact with him,” Bren said, and with a little bow went straight to Sabin, into, at the moment, dangerous territory.

“The dowager, Captain, wishes to speak to Lord Geigi as quickly as possible.”

“Jules. Is Lord Geigi available? The dowager wants to talk to him.”

A little delay.

“We can get him,” Ogun said.

“C2,” Sabin said sharply. That was the second communications post, as she was using Cl’s offices. “Get linked up to the station atevi and get the dowager a handheld. Get her through to whoever she wants.”

Finding the handheld was a reach under the counter, for C2. Finding Lord Geigi in the middle of his night was likely to take a moment, and Bren took the handheld back to Cenedi, who would manage the technicalities of the connection for Ilisidi.

“They are trying,” he informed the dowager, and met a worried, eye-level stare from Cajeiri, who asked no questions of his elders, but who clearly understood far too much.

“I’ll see what I can learn from my office,” Gin said, and crossed the deck to occupy another of the several communications stations, and to borrow another handheld. She would be looking for contact with the station’s Island-originated technical staff, in the Mospheiran sections of the station.

For a moment the paidhi stood in the vacuum-eye of a hurricane, in a low availability of information surrounded by total upheaval, and didn’t know what direction to turn first. But Jase was his information source and Jase had moved up next to Sabin, who was still asking Ogun questions. The two voices, considerably lagged, echoed over the crew-area address.

“Is the station peaceful?”

“Yes,” Ogun was able to say. “We’re holding our own up here. Everyone aboard is cooperating, in full knowledge of the seriousness of the crisis. We are in contact with the government on Mospheira, and they’re arguing about whether to pull out all stops building a shuttle or maybe supply rockets, but right now the question is stalled in their legislature, and no few are arguing for an anti-missile program… ”

Good, loving God. The world had lost its collective mind. Missile defense? Missiles, coming from the mainland against Mospheira?

When he’d taken office, they’d been quarreling about routes for roads and rail transport for a continent mostly rural. Television had been a newborn scandal, an attraction threatening the popularity of the traditional machimi. There had just been airplanes.

And suddenly there were missiles, as a direct, profane result of the space program he’d worked for a decade to institute? Damn it all!

Cenedi was talking to Lord Geigi’s head of security, meanwhile, and he picked up one side of that conversation, which Banichi and Jago could follow on their own equipment. He recalled belatedly that he carried his own small piece of ship’s equipment in his pocket, that he’d picked it up when he left the apartment this morning. He pulled it out, used a fingernail to dial the setting to 2, the channel they were using to get to Geigi, and shoved it hard into his ear.

Geigi was being given a phone. He imagined a very disturbed Geigi, a plump man caught abed by the ship’s return, but Geigi was never the sort to sit idly by while a situation was developing. Geigi would be at least partway dressed by now, his staff scrambling on all levels, knowing their lord would be wanting information on every front.

“To whom am I speaking?” Geigi’s deep voice, unheard for two years, was unmistakable and oh, so welcome.

“I am turning the phone over to the aiji-dowager, nandi, immediately.”

Cenedi did so, while, in Bren’s other ear, Sabin continued in hot and heavy converse with Ogun. He hoped Gin was following the exposition, too—a chronicle of disaster and shortage on the station, with remarkably good behavior from the inhabitants, who had pitched in to conserve and work overtime. Ogun had concentrated all their in-orbit ship-building resources into mining-bots, attempting to secure metals and ice, most of all to build those tanks for food production—a steep, steep production demand, with a very little seed of algaes and yeasts. The ship could have helped—if she weren’t carrying four thousand more mouths to feed.

“Geigi. Geigi-ji,” Ilisidi said. She never liked telephones, or fancy pocketcoms, and she tended to raise her voice when she absolutely had to use one. “One hears entirely unacceptable news.”

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi said. “One is extremely glad of your safe return, particularly in present circumstances. The aishidi’tat, one regrets to say, has fractured.”

The Western Association. Civil war.

“And my grandson?”

“Missing, vanished. One hesitates to say—but the rumor holds he was assassinated in a conspiracy of the Kadigidi—”

“The Kadigidi!” Outrage fired Ilisidi’s voice.

“And the Marid Tasigin. The assassination is unconfirmed, aiji-ma, and many believe the aiji is in hiding and forming plans to return. But your safe return and the heir’s is exceedingly welcome to all of us on the station. Man’chi is unbroken here, on my life, aiji-ma.”

Man’chi. That inexplicable emotional surety of connection and loyalty. The instinct that drove atevi society to associate together. Man’chi between Geigi and the dowager was holding fast. That down on the planet was not faring as well—if one could ever expect loyalty of the Marid Tasigin, which had always been a trouble spot in the association. The Kadigidi lord, on the other hand—if it was Murini—had been an ally.

“We are confident in your estimation,” Ilisidi said. Aijiin had died, accepting such assurances from persons who then turned out to be on the other side, but Bren agreed with her assessment. The Kadigidi and the Marid Tasigin might rebel, but never the Edi, under Lord Geigi, and up here. The western peninsula, Lord Geigi’s region, would hold for Tabini, even if they could not find him—a situation which, Bren insisted to himself, did not at all mean that Tabini was dead. Tabini was not an easy man to catch.

“Our situation on the station,” Geigi said further, “is at present precarious, aiji-ma, in scarcity of food, in the disheartenment which necessarily attends such a blow to the Association. We have waited for you. We have waited for you, expecting your return, while attempting to strengthen our situation, and we have broadcast messages of encouragement to supporters of the aishidi’tat, through the dish on Mospheira. We have asked the presidenta of Mospheira to recognize the aishidi’tat as continuing in authority aboard this station, which he has done by vote of his legislature.”

Good for Shawn Tyers. Good for him. The President was an old friend of his. The Mospheiran legislature took dynamite to move it, but move it must have, to take a firm and even risky decision.

“When did this attack happen, nandi?” Ilisidi asked.

“Eight months ago, aiji-ma.” Shortly after they had set out from Reunion homeward. “Eight months ago assassins struck in Shejidan, taking the Bu-javid while the aiji was on holiday at Taiben. The Kadigidi and the Taisigini declared themselves in control, and attempted to claim that they had assassinated the aiji, but Tabini-aiji broadcast a message that he was alive and by no means recognized their occupation of the capital. The Kadigidi attempted to engage the Assassins’ Guild on their side, but the Guild refused their petition and continued to regard the matter as unsettled. The aiji meanwhile went on to the coast, to Mogari-nai.”

That was the site of the big dish, the site of atevi communications with the station.

“… but the Kadigidi struck there, as well. For several months thereafter we have heard rumors of the aiji’s movements, and we do not despair of hearing from him soon, aiji-ma. He may well send word once he hears you are back.”

“Or he may not,” Ilisidi said, “if he is not yet prepared. He may let opposition concentrate on us.”

“True,” Geigi said. “But we have not heard news lately. The Kadigidi have never since dared claim he is dead. But they may advance such a claim in desperation, Sidi-ji, now that you have arrived.”

“Well,” Ilisidi said, as taken aback as Bren had ever seen her. She stood there staring at nothing in particular, and Cajeiri stood by, looking to her for answers. As they all did. “Well,” she said again.

Jase, meanwhile, had been carrying on a running translation for Sabin, who stood, likewise looking at Ilisidi.

“Where,” Ilisidi asked Geigi sharply, “where is Tatiseigi?”

Cajeiri’s great-uncle, lord of the Atageini, sharing a boundary with the Kadigidi.

“At his estate, aiji-ma. Apparently safe. The Lady Damiri is not there.”

Cajeiri’s mother, who owed direct allegiance to the Atageini lord, Tatiseigi. Damiri was, very possibly, traveling with Tabini, if he was alive. She could have sheltered with her uncle, but apparently she was missing right along with Tabini, still loyal, and a constraint on her great-uncle.

“How many provinces are now joining in this rebellion?”

“Four provinces in the south, two in the east, under Lord Darudi.”

“There is a head destined to fall,” Ilisidi said placidly. “And Tatiseigi? His man’chi?”

“His neighbors the Kadigidi are surely watching him very closely, as if he might harbor the aiji or the consort, but he will not commit to this side or the other and they dare not touch him because of the Northern Association.”

“The Northern Association holds?”

“It holds, aiji-ma.”

It was worth a deep, long sigh of relief. Atevi didn’t have borders. They had overlapping spheres of influence and allegiance. Within the aishidi’tat there were hundreds of associations of all sizes, from two or three provinces, likewise hazy in border, give or take, commonly, the loyalty of two or three families within the overlap. And if the Northern Association had held firm, rallying around Tatiseigi of the Atageini, the Midlands Association, to which the neighboring Kadigidi belonged, would be rash to make a move against Cajeiri’s mother’s relatives.

And Cajeiri arriving back in the picture gave Uncle Tatiseigi a powerful claimant to power from his household, which would bring all sorts of pressure within Tatiseigi’s association… God, it had been so long since he had traced the mazes of atevi clans and allegiances, or had to wonder where the Assassins’ Guild was going to come down on an issue.

Tabini missing. Assassinations. Havoc in the aishidi’tat.

One thing occurred to him, one primary question.

“Where are the shuttles, aiji-ma? Have they survived this disorder?”

“Excellent question,” Ilisidi said, and relayed it to Geigi. “Where are the shuttles?”

“We have one shuttle docked at the station,” was Geigi’s very welcome answer. “But we have no safe port to land it. The rebels hold the seacoast. We fear it may suffer attack, even if we attempt a landing on Mospheira.”

God. But they still had one functional shuttle.

One.

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi said, “I have maps. I have maps, and letters, which I can send to you for more detailed information, if the station and the ship will permit.”

Jase had translated that. They suddenly had Sabin’s full attention. “Jules,” Sabin said to her conversant, “Lord Geigi wants to transmit documents.”

“He should send them,” Bren said, “aiji-ma.”

“I shall get them together,” Lord Geigi said, when she ordered the transmission. “And I shall be there to meet you when you dock, aiji-ma.”

“A cold trek and pointless,” was Ilisidi’s response. “Order my staff and the paidhi’s to prepare our rooms and never mind coming to that abysmally uncomfortable dock. We shall meet you in decent comfort, Geigi-ji, as soon as possible. If you think of other matters, include them with your documents. I am handing this phone back now.”

“Yes,” Geigi said, accepting orders, and the contact went dead.

Bren stood still, numb, and glanced at Jase.

“I translated,” Jase said, with a shift of the eyes toward Sabin.

“We have a problem, it seems,” Sabin said. “We have a shuttle, a ship full of more mouths to feed—we do have our own ship’s tanks, which should suffice to feed us all and the station, not well, but adequately, so at least we won’t overburden their systems. And we have our additional miner-bots, slow as that process may be.”

“We have our own manufacturing module,” Gin said. “And we have some supplies. We can start assembly and programming on extant stock as soon as we dock. We can get them to work in fairly short order, and see if we can pick up the pace of their operation.”

“Good,” Sabin said shortly.

In one word, from high hopes and the expectation of luxury back to a situation of shortage and the necessity of mining in orbit, the condition of life of their ancestors. The condition of the great-grandfathers of the Reunioners, too, who had had to build their distant station in desolation and hazard, by their own bootstraps.

They had to break that news to four thousand-odd colonists, and still keep the lid on their patience. Four thousand desperate people who’d been promised the sun and the moon and fruit drops forever once they got to the home station—and they were back to a hard-scrabble existence, with a revolution in progress down in the gravity well.

The gravity well. That long, long drop. Bren felt a sensation he hadn’t felt in two years, the sensation of standing at the top of a dizzying deep pit, at the bottom of which lay business he couldn’t let go its own course.

Tabini. Atevi civilization. Toby and his own family, such as he had.

“Mani-ma.” Cajeiri, ever so quietly, addressing his great-grandmother. “Do you think my father and mother are still alive?”

Ilisidi gave a snort. “The Kadigidi would wish it known if not. Evidently they dare not claim it, even if they hope it to be the case, and one doubts they have so much as a good hope of being right. Likely your father and mother are alive and waiting for us to descend with force from the heavens.”

“Shall we, mani-ma?”

“As soon as possible,” Ilisidi said, and looked at Bren. “Shall we not?”

“How long until dock?” Bren asked the captains.

A flat stare from Sabin. “A fairly fast passage. When we get there, we’re going to be letting these passengers off in small packets. Very small packets. Their quarters have to be warmed and provisioned.”

They could warm a section at a time, and would, he was very sure; but they could also do it at their own speed, which was likely to be very slow. Sabin meant she was not going to have a general debarcation, no celebration, no letting their dangerous cargo loose wholesale.

And Gin Kroger had to get at her packaged robots and get the manufactory unpacked.

“I very well understand,” he said with a bow of his head that was automatic by now, to atevi and to humans. “I think it wise, for what it’s worth.”

“Our passengers are stationers,” Sabin said. “Spacers. They understand fragile systems. They won’t outright riot. But small conspiracies are dangerous—with people that understand fragile systems. I’m going to request Ogun to invoke martial law on the station until we completely settle these people in—simplifying our problems of control. I trust you can make this understood among atevi. I trust there’s not going to be some coup on that side of the station.”

There was very little human behavior that could not be passed off among atevi with a shrug. But emotions would be running high there, too, considering the dowager’s return.

“We don’t likely have any Kadigidi sympathizers on station,” Bren said quietly. “No. But there may be high feelings, all the same, with the return of the aiji’s son, and the only general translation of martial law doesn’t mean no celebration. No one can lay a hand on him or the dowager, no matter whose rules they violate.”

“Understood,” Sabin said. “That will be made very clear to our personnel. I trust the dowager to manage hers.” She drew a deep breath, set hands on hips and looked across the bridge. “We’re inertial for the station. Before we make connection with the core, we’ve got to decide whether to run the dowager aboard at high speed, or be prepared to sit it out and establish our set of rules first. I’m inclined to get your party aboard first, if you can guarantee quiet once you’re there.”

“Yes,” Bren said. Absolutes made him nervous as hell, but he had laid his life on Geigi’s integrity often enough before this. “We’ll take the fast route in, straight into the atevi section. Humans may be excited to know she’s here. That’s my chief worry. They’ll want to see her.”

“No question they’ll be excited,” Jase said.

Ilisidi was popular on the station, even among humans. Ilisidi always had been. And right now people were desperate for authority.

“I’d suggest we not discuss our boarding,” Bren said. “If we get Geigi’s men positioned near the lift, we can get into our own section fast and just not answer the outside. Stationers know better than to rush atevi security.”

“You go on station with them,” Sabin said to Jase. “I want you in direct liaison with Ogun.”

“We can trickle the Reunioners on, three to five at a time,” Jase said quietly, “Drag out the formalities, mandatory orientations—rules and records-keeping they understand. The technical problems of warming a section for occupation, they well understand.”

“Register them to sponsors,” Gin put in, “to our people, who know atevi.”

It wasn’t the first time Gin had put forward that idea, and they’d shot it down, not wanting to create a class difference between Mospheirans and Reunioners. But right now it made thorough sense to do it… a sense that might reverberate through human culture for centuries if they weren’t careful.

“All that’s Graham’s problem,” Sabin said shortly, meaning Jase had to make that decision among a thousand others, and she knew what he’d choose. “My whole concern is the security of this ship, its crew, and its supply. So are your atevi going to time out on us for an internal war, Mr. Cameron? Or can you explain to them we might see strangers popping into the system for a visit at any time from now on? I’d really rather have our affairs in better order when that happens.”

“I intend to make that point,” Bren said.

“Make it, hard. We need those shuttles. That would solve an entire array of problems. In the meantime, Ms. Kroger, I need your professional services, and will need them, urgently and constantly for the foreseeable future. Captain Ogun’s got his mining operation going all-out here, but if Cameron can’t get atevi resources up to us off the planet, or can’t get them tomorrow, we’ve got the immediate problem of feeding this lot—and I’m not ready to rip the shipyard apart worse than it already is to get supply. I want Captain Ogun’s tanks, Ms. Kroger. Shielded tanks and water sufficient to handle the station population indefinitely.”

“Understood,” Gin said.

“Then everybody get moving,” Sabin said.

Bren translated for the dowager. “The ship-aijiin recommend we go below and make final preparations to leave the ship, which will be a hurried transit, aiji-ma, into a disturbed population.”

“We are prepared,” Ilisidi said with a wave of her hand. The dowager had acquired a certain respect for Sabin-aiji, after a difficult start—a respect particularly active whenever Sabin’s opinion coincided with hers. “We are always prepared. Tell her see to her own people.”

“The dowager states she is prepared for any eventuality.” There were times he didn’t translate all of what one side said; and there were times he did. “The aiji-dowager expects you to control the human side of this. She is prepared to make inroads into the atevi situation.”

“Go below and observe takehold,” Sabin said. “The lot of you. We’re not wasting any time getting in there, no time for more ferment on their side or ours, thank you.”

“Aiji-ma,” Bren translated that. “The ship is about to move with greater than ordinary dispatch and Sabin-aiji politely urges us all to take appropriate shelter belowdecks for a violent transit. This will speed us in before there can be further disturbance on the station or among our human passengers.”

“Good,” Ilisidi said sharply and headed for the lift, marking her path with energetic taps of the cane. Her great-grandson and the rest of her company could only make haste behind her to reach the doors, while the ship sounded the imminent-motion warning.

It was certainly not the homecoming they’d planned. Damn, Bren thought bleakly, taking his place inside the lift car. They’d ridden from nervous anticipation to the depths of anxiety all in an hour; and amid everything else—

Amid everything else, he thought, looking across the car at Cajeiri, there’d been no special word for a boy who’d just heard bad news about his mother and father, and who remained appallingly quiet.

What did he say to an atevi child? Or what should his great-grandmother have said, or what dared he say now?

The lift moved. Meanwhile the intercom gave the order: “Maneuvers imminent. Takehold and brace for very strong movement.”

Four thousand colonists were getting that news, people unacculturated to the delicate and dangerous situation they were going to land in on the station, people whose holier-than-common-colonists attitudes were even more objectionable to the Mospheirans who were half the workforce on that station, and whose ancestors had suffered under Guild management… and who were going to have to sponsor the Reunioners if, as seemed likely now, Gin’s plan prevailed.

Four thousand people who’d been promised paradise ended up on tighter rations than they’d had where they’d come from. And the Mospheirans, who were going to have to live with them and who’d already endured hardship since the shuttles had stopped flying, weren’t going to be anywhere near as patient with their daily complaints as the ship had been.

Jerry and Gin were holding quiet, rapid-fire consultations next to him, Jerry agreeing to stay aboard the ship while Gin went to her on-station offices to take control. Banichi was holding quick converse with Cenedi.

The lift hit five-deck level and opened for them. Gin and Jerry went one way, they went another, past sentries, into the atevi section.

“Aiji-ma,” Bren said, prepared to take his leave and deal with his own staff. “Nandi.” For the youngster, who gravely bowed. He remained distressed for the boy, the heir, who might in some atevi minds on that station now be the new aiji of Shejidan; but none of them had time to discuss their situation or accommodate an eight-year-old boy’s natural distress—not in a ship about to undertake maneuvers. Beyond that, he reminded himself, Cajeiri’s whole being responded to man’chi, a set of emotions a human being was only minimally wired to understand. For all he knew, the boy was approaching the explosion point. Every association of the boy’s life was under assault, while atevi under him and around him in the hierarchy would rally round and carry on with all the resources the battered association could rake together. God knew what the boy was feeling, or whether he was just numb at the moment, or how he would react when the whole expectations of the station atevi centered on him.