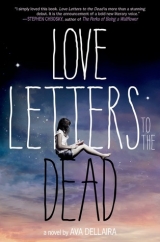

Текст книги "Love Letters to the Dead"

Автор книги: Ava Dellaira

Жанр:

Подростковая литература

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my mother, Mary Michael Carnes

I carry your heart

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Begin Reading

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Resources

Copyright

Dear Kurt Cobain,

Mrs. Buster gave us our first assignment in English today, to write a letter to a dead person. As if the letter could reach you in heaven, or at the post office for ghosts. She probably meant for us to write to someone like a former president or something, but I need someone to talk to. I couldn’t talk to a president. I can talk to you.

I wish you could tell me where you are now and why you left. You were my sister May’s favorite musician. Since she’s been gone, it’s hard to be myself, because I don’t know exactly who I am. But now that I’ve started high school, I need to figure it out really fast. Because I can tell that otherwise, I could drown here.

The only things I know about high school are from May. On my first day, I went into her closet and found the outfit that I remember her wearing on her first day—a pleated skirt with a pink cashmere sweater that she cut the neck off of and pinned a Nirvana patch to, the smiley face one with the x-shaped eyes. But the thing about May is that she was beautiful, in a way that stays in your mind. Her hair was perfectly smooth, and she walked like she belonged in a better world, so the outfit made sense on her. I put it on and stared at myself in front of her mirror, trying to feel like I belonged in any world, but on me it looked like I was wearing a costume. So I used my favorite outfit from middle school instead, which is jean overalls with a long-sleeve tee shirt and hoop earrings. When I stepped into the hall of West Mesa High, I knew right away this was wrong.

The next thing I realized is that you aren’t supposed to bring your lunch. You are supposed to buy pizza and Nutter Butters, or else you aren’t supposed to even eat lunch. My aunt Amy, who I live with every other week now, has started making me iceberg lettuce and mayonnaise sandwiches on kaiser rolls, because that’s what we liked to have, May and I, when we were little. I used to have a normal family. I mean, not a perfect one, but it was Mom and Dad and May and me. Now that seems like a long time ago. But Aunt Amy tries hard, and she likes making the sandwiches so much, I can’t explain that they aren’t right in high school. So I go into the girls’ bathroom, eat the kaiser roll as quickly as I can, and throw the paper bag in the trash for tampons.

It’s been a week, and I still don’t know anyone here. All the kids from my middle school went to Sandia High, which is where May went. I didn’t want everyone there feeling sorry for me and asking questions I couldn’t answer, so I came to West Mesa instead, the school in Aunt Amy’s district. This is supposed to be a fresh start, I guess.

Since I don’t really want to spend all forty-three minutes of lunch in the bathroom, once I finish my kaiser roll I go outside and sit by the fence. I turn myself invisible so I can just watch. The trees are starting to rain leaves, but the air is still hot enough to swim through. I especially like to watch this boy, whose name I figured out is Sky. He always wears a leather jacket, even though summer is barely over. He reminds me that the air isn’t just something that’s there. It’s something you breathe in. Even though he’s all the way across the school yard, I feel like I can see his chest rising up and down.

I don’t know why, but in this place full of strangers, it feels good that Sky is breathing the same air as I am. The same air that you did. The same air as May.

Sometimes your music sounds like there’s too much inside of you. Maybe even you couldn’t get it all out. Maybe that’s why you died. Like you exploded from the inside. I guess I am not doing this assignment the way I am supposed to. Maybe I’ll try again later.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Kurt Cobain,

When Mrs. Buster asked us to pass our letters up at the end of class today, I looked at my notebook where I wrote mine and folded it closed. As soon as the bell rang, I hurried to pack my stuff and left. There are some things that I can’t tell anyone, except the people who aren’t here anymore.

The first time May played your music for me, I was in eighth grade. She was in tenth. Ever since she’d gotten to high school, she seemed further and further away. I missed her, and the worlds we used to make up together. But that night in the car, it was just the two of us again. She put on “Heart-Shaped Box,” and it was like nothing I’d ever heard before.

When May turned her eyes from the road and asked, “Do you like it?” it was as if she’d opened the door to her new world and was asking me in. I nodded yes. It was a world full of feelings that I didn’t have words for yet.

Lately, I’ve been listening to you again. I put on In Utero, close the door and close my eyes, and play the whole thing a lot of times. And when I am there with your voice, it’s hard to explain it, but I feel like I start to make sense.

After May died last April, it’s like my brain just shut off. I didn’t know how to answer any of the questions my parents asked, so I basically stopped talking for a little while. And finally we all stopped talking, at least about that. It’s a myth that grief makes you closer. We were all on our own islands—Dad in the house, Mom in the apartment she’d moved into a few years before, and me bouncing back and forth in silence, too out of it to go to the last months of middle school.

Eventually Dad turned up the volume on his baseball games and went back to work at Rhodes Construction, and Mom left to go away to a ranch in California two months later. Maybe she was mad that I couldn’t tell her what happened. But I can’t tell anyone.

In the long summer sitting around, I started looking online for articles, or pictures, or some story that could replace the one that kept playing in my head. There was the obituary that said May was a beautiful young woman and a great student and beloved by her family. And there was the one little article from the paper, “Local Teen Dies Tragically,” accompanied by a photo of flowers and things that some kids from her old school left by the bridge, along with her yearbook picture, where she’s smiling and her hair is shining and her eyes are looking right out at us.

Maybe you can help me figure out how to find a door to a new world again. I still haven’t made any friends yet. I’ve actually hardly said a single word the whole week and a half I’ve been here, except “present” during roll call. And to ask the secretary for directions to class. But there is this girl named Natalie in my English class. She draws pictures on her arms. Not just normal hearts, but meadows with creatures and girls and trees that look like they are alive. She wears her hair in two braids that go down to her waist, and everything about her dark skin is perfectly smooth. Her eyes are two different colors—one is almost black, and the other is foggy green. She passed me a note yesterday with just a little smiley face on it. I am thinking that maybe soon I could try to eat lunch with her.

When everyone stands in line at lunch to buy stuff, they all look like they are standing together. I couldn’t stop wishing that I was standing with them, too. I didn’t want to bother Dad about asking for money, because he looks stressed out whenever I do, and I can’t ask Aunt Amy, because she thinks I am happy with the kaiser rolls. But I started collecting change when I find it—a penny on the ground or a quarter in the broken soda machine, and yesterday I took fifty cents off of Aunt Amy’s dresser. I felt bad. Still, it made enough to buy a pack of Nutter Butters.

I liked everything about it. I liked waiting in line with everyone. I liked that the girl in front of me had red curls on the back of her head that you could tell she curled herself. And I liked the thin crinkle of the plastic when I opened the wrapper. I liked how every bite made a falling-apart kind of crunch.

Then what happened is this—I was nibbling a Nutter Butter and staring at Sky through the raining leaves. That’s when he saw me. He was turning to talk to someone. He went into slow motion. Our eyes met for a minute, before mine darted away. It felt like fireflies lighting under my skin. The thing is, when I looked back up, Sky was still looking. His eyes were like your voice—keys to a place in me that could burst open.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Judy Garland,

I thought of writing to you, because The Wizard of Oz is still my favorite movie. My mom would always put it on when I stayed home sick from school. She would give me ginger ale with pink plastic ice cubes and cinnamon toast, and you would be singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

I realize now that everyone knows your face. Everyone knows your voice. But not everyone knows where you were really from, when you weren’t from the movies.

I can imagine you as a little girl on a December day in the town where you grew up on the edge of the Mojave Desert, tap-tap-tap-dancing onstage in your daddy’s movie theater. Singing your jingle bells. You learned right away that applause sounds like love.

I can imagine you on summer nights, when everyone would come to the theater to get out of the heat. Under the refrigerated air, you would be up onstage, making the audience forget for the moment that there was anything to be afraid of. Your mom and dad would smile up at you. They looked the happiest when you were singing.

Afterward, the movie would pass by in a blur of black and white, and you would get suddenly sleepy. Your daddy would carry you outside, and it was time to drive home in his big car, like a boat swimming over the dark asphalt surface of the earth.

You never wanted anyone to be sad, so you kept singing. You’d sing yourself to sleep when your parents were fighting. And when they weren’t fighting, you’d sing to make them laugh. You used your voice like glue to keep your family together. And then to keep yourself from coming undone.

My mom used to sing me and May to sleep with a lullaby. Her voice would croon, “all bound for morning town…” She would stroke my hair and stay until I slept. When I couldn’t sleep, she would tell me to imagine myself in a bubble over the sea. I would close my eyes and float there, listening to the waves. I would look down at the shimmering water. When the bubble broke, I would hear her voice, making a new bubble to catch me.

But now when I try to imagine myself over the sea, the bubble pops right away. I have to open my eyes with a start before I crash. Mom is too sad to take care of me. She and Dad split up right before May started high school, and after May died almost two years later, she went all the way to California.

With just Dad and me at our house, it’s full of echoes everywhere. I go back in my mind to when we were all together. I can smell the sizzle of the meat from Mom making dinner. It sparkles. I can almost look out the window and see May and me in the yard, collecting ingredients for our fairy spells.

Instead of staying with Mom every other week like May and I did after the divorce, now I stay with Aunt Amy. Her house is a different kind of empty. It’s not full of ghosts. It’s quiet, with shelves set up with rose china, and china dolls, and rose soaps meant to wash out sadness. But always saved for when they are really needed, I guess. We just use Ivory in the bathroom.

I am looking out the window now in her cold house, from under the rose quilt, to find the first star.

I wish you could tell me where you are now. I mean, I know you’re dead, but I think there must be something in a human being that can’t just disappear. It’s dark out. You’re out there. Somewhere, somewhere. I’d like to let you in.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Elizabeth Bishop,

I want to tell you about two things that happened in English today. We read your poem, and I talked in class for the first time. I’ve been in high school for two weeks now, and so far I had been spending most of the period looking out the window, watching the birds flying between phone wires and twinkling aspens. I was thinking about this boy, Sky, and wondering what he sees when he closes his eyes, when I heard my name. I looked up. The birds’ wings started beating in my chest.

Mrs. Buster was staring at me. “Laurel. Will you read?”

I didn’t even know what page we were on. I could feel my mind going blank. But then Natalie leaned over and flipped my Xerox to the right poem. It started like this:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

At first, I was so nervous. But while I was reading, I started listening, and I just understood it.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

I think my voice might have been shaking too much, like the poem earthquaked me. The room was dead quiet when I stopped.

Mrs. Buster did what she does, which is to stare at the class with her big bug eyes and say, “What do you think?”

Natalie glanced in my direction. I think she felt bad because everyone was looking not at Mrs. Buster, but at me. So she raised her hand and said, “Well, of course she’s lying. It’s not easy to lose things.” Then everyone stopped looking at me and looked at Natalie.

Mrs. Buster said, “Why are some things harder to lose than others?”

Natalie had a no-duh sound in her voice when she answered. “Because of love, of course. The more you love something, the harder it is to lose.”

I raised my hand before I could even think about it. “I think it’s like when you lose something so close to you, it’s like losing yourself. That’s why at the end, it’s hard for her to write even. She can hardly remember how. Because she barely knows what she is anymore.”

The eyes all turned back to me, but after that, thank god, the bell rang.

I gathered up my stuff as quickly as I could. I looked over at Natalie, and she looked like maybe she was waiting for me. I thought this might be the day that she would ask if I wanted to eat lunch with her and I could stop sitting at the fence.

But Mrs. Buster said, “Laurel, can I talk to you a moment?” I hated her then, because Natalie left. I shifted in front of her desk. She said, “How are you doing?”

My palms were still sweaty from talking in class. “Um, fine.”

“I noticed that you didn’t turn in your first assignment. The letter?”

I stared down at the fluorescent light reflected in the floor and mumbled, “Oh, yeah. Sorry. I didn’t finish it yet.”

“All right. I’ll give you an extension this time. But I’d like you to get it to me by next week.”

I nodded.

Then she said, “Laurel, if you ever need anyone to talk to…”

I looked up at her blankly.

“I used to teach at Sandia,” she said carefully. “May was in my English class her freshman year.”

My breath caught in my chest. I started to feel dizzy. I had counted on no one here knowing, or at least no one talking about it. But now Mrs. Buster was staring at me like I could give her some kind of answer to an awful mystery. I couldn’t.

Finally Mrs. Buster said, “She was a special girl.”

I swallowed. “Yeah,” I said. And I walked out the door.

The noise in the hallway changed into the loudest river I’ve ever heard. I thought maybe I could close my eyes and all of the voices would carry me away.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear River Phoenix,

May’s room at my dad’s house is just like it always was. Exactly the same, only the door stays closed and not a sound comes out. Sometimes I’ll wake up from a dream and think I hear her footsteps, sneaking back home after a night out. My heart will beat with excitement and I’ll sit up in bed, until I remember.

If I can’t fall back asleep, I get up and tiptoe down the hall, turn the handle of the door so it doesn’t creak, and walk into May’s room. It’s as if she never left. I notice everything, just the same as it was when we went to the movies that night. The two bobby pins in a cross on the dresser. I pick them up and put them in my hair. Then I put them back in the same exact cross, pointing toward an almost empty bottle of Sunflowers perfume and the tube of bright lipstick that was never on when she left the house, but always when she came back. The top of her bookshelf is lined with collections of heart-shaped sunglasses, half-burned candles, seashells, geodes split in their centers to show their crystals. I lie on her bed and look up at her things and try to imagine her there. I stare at the bulletin board covered with dried flowers pinned with tacks, little ripped-out horoscopes, and photographs. One of us when we were little, in a wagon next to Mom in the summer. One taken before prom where she wore a long lingerie dress she found at Thrift Town, the same rose in her hair that is now dried and pinned there.

I open May’s closet and look at the sparkly shirts, the short skirts, the sweaters cut at the neck, the jeans ripped at the thighs. Her clothes are brave like she was.

On the wall above her bed hangs a Nirvana poster, and next to it, there’s a picture of you from Stand by Me. You have a cigarette half in your mouth, cheekbones carved from stone, and baby blond hair. My sister loved you. I remember the first time we saw the movie. It was right before Mom and Dad split up, and right before May started high school. We were up late together, just the two of us, with a pile of blankets and a tin of Jiffy Pop that May made for us, and it came on TV. It was the first time either of us had seen you. You were so beautiful. But even more than that, you were somebody we felt like we recognized. In the movie, you were the one to take care of Gordie, who’d lost his older brother. You were his protector. But you had your own hurt, too. The parents and the teachers and everyone thought badly of you because of your family’s reputation. When you said, “I just wish I could go someplace where no one knows me,” May turned to me and said, “I wish I could pull him out of the screen and into our living room. He belongs with us, don’t you think?” I nodded that I did.

By the end of the movie, May had declared that she was in love with you. She wanted to know what you were like now, so we went on Dad’s computer and May looked you up. There were all of these pictures of you, some from Stand by Me and some from when you got older. In all of them, you were vulnerable and tough at once. And then we saw that you’d died. Of a drug overdose. You were only twenty-three. It was like the world stopped. You’d been just right there, almost in the room with us. But you were no longer on this earth.

When I think back to it, that night seems like the beginning of when everything changed. Maybe we didn’t have the words for it then, but when we found out you’d died, it’s like the first time that we saw what could happen to innocence. Finally May shut off the computer and wiped the tears from her eyes. She said you’d always be alive for her.

Whenever we saw Stand by Me after that (we got the DVD and watched it over and over that summer), we always muted the part at the end where Gordie said that your character, Chris, got killed. We didn’t want that. The way you looked, with the light haloed around your head—you were a boy, a boy who would become a real man. We wanted to just see you there, perfect and eternal forever.

I know May’s dead. I mean, I know it in my head, but it doesn’t seem real. I still feel like she’s here, with me somehow. Like one night she’ll crawl in through her window, back from sneaking out, and tell me about her adventure. Maybe if I can learn to be more like her, I will know how to be better at living without her.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Amelia Earhart,

I remember when I first learned about you in social studies in middle school, I was almost jealous. I know that’s the wrong way to feel about someone who died tragically, but it wasn’t so much the dying I was jealous of. It was the flying, and the disappearing. The way you saw the earth from the air. You weren’t scared of getting lost. You just took off.

I decided this morning that I really need even the tiniest bit of the courage that you had because I started high school almost three weeks ago, and I can’t keep sitting alone by the fence anymore. So after I looked through all of my old clothes, which are terrible no matter how much I try to pick the most inconspicuous ones, I went and opened May’s closet and looked at it, full of bright, brave things. I remembered her body filling them. She would leave in the morning with her backpack slung over her shoulder, and it seemed that everything outside of our door must have rushed forward to greet her. I took her first day outfit—a pink cashmere sweater with a Nirvana patch on it and a short pleated skirt. I put it on. I didn’t look in the mirror this time, because I knew it would scare me out of wearing it. I just paid attention to the swish of the skirt against my bare legs and thought of how May must have felt in it.

In the car with Dad on the way to school, I could feel his eyes on me. Finally, as he pulled up to the drop-off line, he said carefully, “You look nice today.”

I knew that he recognized the outfit was May’s. “Thanks, Dad,” I said, and nothing more. I gave him a little smile and jumped out of the car.

Then at lunch, I walked through the cafeteria to the outdoor tables and watched everyone swirling together, looking happy, like they should all be part of the same movie. I saw Natalie from my English class with this blazing redheaded girl. They sat down at a table together in the middle of the crowd. They both had Capri Suns and no food. They looked like the sunlight had landed on purpose right in their hair. Natalie had her pigtail braids and drawn-on tattoos and wore a Batman tee shirt that was tight across her chest. The redhead had on a black ballerina skirt and a bright red scarf, with lipstick to match. They weren’t dressed like the popular girls, who look clean and cut out of a magazine. But to me, they were beautiful, like their own constellation. Like one that maybe I could belong in. They looked like girls who would have been May’s friends. They shooed off the soccer boys who swarmed around the redhead.

I wanted to sit by them so badly I could feel it in my whole body. I started to walk toward them, thinking maybe Natalie would notice me. But I got nervous and walked back to sit down by the fence. I stood up and sat down again.

I remembered what you said—There’s more to life than being a passenger. I thought of you soaring through the sky. I thought of May rushing out in the morning. I ran my hands over her sweater I was wearing. And I walked over. When I got close to the table, I sort of just stood there, a few feet away. They were in the middle of leaning in and trading Capri Suns, so they each got a new flavor, when they felt a body and looked up. I think they thought it would be another soccer boy, and Natalie looked annoyed at first. But her face turned nice when she recognized me. I tried so hard to think of something to say, but I couldn’t. The voices rushed around me, and I started to blank out.

But then I heard Natalie. “Hey. You’re in my English class.”

“Yeah.” I took my chance and sat down at the end of the bench.

“I’m Natalie. This is Hannah.”

“I’m Laurel.”

Hannah looked up from her Capri Sun. “Laurel? That’s the coolest name ever.”

Natalie started talking about the “lame-os” in our class, and I was doing my best to follow along, but really, I was so happy to be there I couldn’t focus on what she was saying.

By the end of lunch, they’d liked my skirt and my whole outfit and asked me if I wanted to go to the state fair after school. I couldn’t believe it. I called Dad on my new cell phone that is supposed to be just for emergencies (although I can tell already that it won’t be). I said that some girls asked me to hang out after school, so not to worry if I wasn’t home yet when he got back from work, and that I’d take the bus afterward like usual. I talked fast so that he wouldn’t have time to object. I’m in algebra now, and I can’t wait for the bell to ring. The numbers on the board don’t mean a thing, because for the first time in forever, I have somewhere to go.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Amelia Earhart,

When we got to the fair, it was good like when I was a kid and sticky like it should be—full of stands selling cowboy hats and airbrushed tee shirts and the smell of state fair food. We were all starved, and the way Natalie and Hannah said it—“I’m starved”—it was easy to say it like them. To fit in.

When we got in line for frilly fries, Hannah started flirting with this guy in front of us. He had a white tank top, slicked-back hair, and a stare that made me think he wanted to bite her. Hannah’s red hair is straight as a board, or so she told me, but she puts it into curlers every day. Her bouncy red curls fall around her face, and her big eyes look like she’s always seeing something incredible. Her lips look like she’s half smiling at something that no one else could get.

I was worried about not having any money and thinking I’d say I wasn’t so hungry after all, but when we got to the front of the line, Hannah let the guy pay for us. He was making me nervous, leaning into Hannah like he was. I kept thinking that he was going to do something, but when we got our fries, she just said thanks and walked off, leaving him staring after her. I think she was showing off a little, but Natalie didn’t act impressed. She just said, “Um, hair gel much?”

After we ate, we went over to the fence to smoke cigarettes. I’d never smoked, and I didn’t know how. I’d seen May do it before, so I tried to copy her. But I guess it was obvious. Natalie laughed so loud that she started coughing. She said, “No, like this,” and she showed me how to keep the smoke in and then suck it down my lungs. That is how you inhale. It made me really dizzy and sort of sick-feeling. By the time we were done, I was walking pretty much in zigzags.

So when Natalie and Hannah were ready for rides, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to go. There was this one, a special ride that costs extra, where they put you in a harness and pull you up, higher than any building in the city. And then they drop you, and you go flying over the whole fair. I finally told them that I’d forgotten to bring money, but Hannah said that she had some from her job and explained that she works a few nights a week as a hostess at a restaurant called Japanese Kitchen.

“She’s so pretty,” Natalie said, smiling at her, “that they hired her even though she’s only fifteen.”

“Shut up,” Hannah said. “It’s because they could tell I would be an excellent employee!”

When she counted out her money, it wasn’t quite enough, but she said that if we flirted with the guy who ran the ride, he’d let us go for less. When we got to the front of the line, my heart was pounding. Part of me hoped the guy would say no, because I was honestly terrified. But Hannah did her best smile, and he agreed to give us a discount. I thought of you and how brave you were in your plane. And how you made other people around you brave, too. And suddenly, all three of us were harnessed together, and he was hoisting us up. While we were waiting to be dropped, we could see all of the tiny people in the fairgrounds. I forgot to be scared. I was thinking about how each one of them, so small from high up, was like their own island, with secret forests and hidden thoughts.

And that’s when he dropped us! With no warning. We were flying. I couldn’t have felt more perfect. Sailing through the late afternoon sun and the smell of roasted corn and frilly fries and funnel cake, above all of the islands. So fast that when I opened my mouth, a whole world of air would come in. Next to the girls who could be my new friends.

I thought of you, watching the earth always changing from above. The tall grass swaying. The rivers like long fingers and the fog from the sea sucking up the shore. And how, when you disappeared down there, you must have become a part of it.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Kurt Cobain,

All weekend I had been worried that Natalie and Hannah might forget about me in school on Monday, but today in English, Natalie passed me a note that said lame-o! with an arrow pointing toward the guy sitting next to me, who was drawing naked boobs on his poem handout. I looked over at her desk and smiled to show that I got the joke. And at lunch, I saw Natalie and Hannah wave to me from their table. My heart leapt. I threw away my lunch bag with its kaiser roll in a quick toss and went to sit by them. Hannah was licking Doritos cheese off her fingers and passed me the bag.

I tried not to look, but after a while, my eyes found Sky. I saw him see me with my new friends. I wondered if the sun landed right on me like it did on them. I imagined growing brighter and let myself look back at him a moment too long.

Hannah caught me. “Who are you looking at?”

I mumbled, “Nobody,” but my cheeks got hot and probably red like an unfortunate truth meter.

Hannah insisted, “Who?! Tell me!”