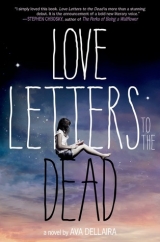

Текст книги "Love Letters to the Dead"

Автор книги: Ava Dellaira

Жанр:

Подростковая литература

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Then I just go around and around. And I still don’t know how to make sense of the world. But maybe it’s okay that it’s bigger than what we can hold on to. Because I think that by beauty, you don’t just mean something that’s pretty. You mean something that makes us human. The urn, you say, is a “friend to man.” It will live beyond its generation, and the next ones. And your poem is like that, too. You died almost two hundred years ago, when you were only twenty-five. But the words that you left are still alive.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Kurt,

I was reading about you tonight, because I wondered what your life was like when you were a kid. You were the center of attention in your family, but after your parents divorced when you were eight, you were orphaned in a way. You were angry. You wrote on your wall: I hate Mom, I hate Dad, Dad hates Mom, Mom hates Dad, it simply makes you want to be sad. You said the pain of their split stayed with you for years. They passed you from one of them to the other. Your dad remarried, and your mom had a boyfriend who was bad to her. By the time you were a teenager, your dad had custody of you, but he passed you off to live with the family of your friend. Then you moved back to live with your mom. When you didn’t graduate high school or get a job, she packed your stuff into boxes and kicked you out. You were homeless then. You stayed on other people’s couches, or sometimes you slept under a bridge, or in the waiting room of the Grays Harbor Community Hospital—a teenager just becoming a man, sleeping alone in the hospital where you were born eighteen years before.

For me, it’s not as bad as it was for you. But I understand how it is when a family falls apart. Tonight is Sunday, the house-switching night. It makes the gloominess of the end of the weekend even worse, putting my things in the little Tinker Bell suitcase that I’ve had since I was eleven. Mom and Dad bought it for me as a consolation prize when they split up.

It was the summer before May started high school. She would turn fifteen at the beginning of the school year. I was going into seventh grade, about to turn twelve that summer. May and I had just finished the waffles that Mom had made us, and then she and Dad said that we had to have a family meeting. We went to sit outside, and although it was morning, it was already hot. The elm trees were raining their twirling airplane seeds. It was Mom who said it. “Your father and I don’t think we can be together any longer. We are going to take some time apart.”

It was hard for me to understand at first what this meant. What I remember most is how hard May cried. She cried like someone had died. Dad kept trying to put his hand on her back, and Mom tried to hug her, but she didn’t want anyone to touch her. She walked away, into a corner of the yard, and curled up. I pulled out one of my eyelashes and hoped that it would count. I didn’t even wish for Mom and Dad to get back together. I wished for May to be okay.

Later that night she said to me, in a voice that was flatter than anything, “I failed.”

“What do you mean?”

“I wasn’t good enough to keep them together.”

I wished I knew what to say back, but I didn’t. “You’re good enough for me,” I said meekly.

May smiled at me, although it was a sad smile. “Thanks, Laurel.” And then she added, “At least we always have each other.”

I made a decision right then that I would love her even more than I already did—enough to make up for everything else.

After that day our lives turned different. Dad stayed in the house, and Mom moved into an apartment, which sort of made it seem obvious that the split was her idea, although they never explained that part of it. The next month May went to high school, and she started to act happy again, but it wasn’t the same. Now she had a new world to be in, and it didn’t include any of us. Something invisible took her. She was there, but gone.

We still did one thing together, all four of us, because Mom and Dad said it was important, which was to have family dinners at the Village Inn like we’d done every Friday since we were kids. It was always strained, Mom and Dad talking mostly to us and not to each other. I was quiet, but May told stories, pretending like everything was normal. The waiters would stare at her. Bucky, the Village Inn bear (i.e., the owner dressed in costume), would come over to our table, even though we weren’t little kids anymore. May played along and flirted with him. She didn’t give Mom and Dad anything to complain about. She was beautiful and smart and she had good grades and talked about lots of friends. But we never saw the girls she used to hang out with in middle school anymore. She was always going out, no one was ever coming over, to either of the houses.

When we were with Dad, he’d let us order stuffed-crust pizza or Chinese takeout, and then he’d retreat to his bedroom. I think he didn’t want us to see him being sad. He still tried to have rules, so May had to sneak out when she wanted to stay out late, but it didn’t seem difficult for her to get away with it.

Mom tried hard during our weeks with her, almost too hard. She got strawberry kiwi tea (May’s favorite and mine, too), and hung prisms in the windows over the dingy brown carpets in her new apartment, and set up her easels, and took us out to dinner at the 66 Diner, which we probably couldn’t afford. Mom would stare at May over milk shakes, her eyes welling with tears, and ask, “Are you mad at me?” May would push her hair back and say, “No,” the crack in her voice barely hidden. May couldn’t just scream I hate you at our parents, the way that some kids can, and know that everything would be okay later. With Mom, it’s like if May did that, she would have crumbled. Whenever May wanted to go out with friends, Mom looked sad, like she felt abandoned or something. But she let her go. She gave her a key and didn’t say when to be home. She wanted to be the cool parent, I guess, or to make up for things.

At first I’d asked to go with May, but May would say I was still too young. So I’d be left in the apartment. Mom would ask, “How do you think your sister is doing?” Or, “Who’s she going out with? There must be a boy, right? Do you think she likes him?” Mom was testing to see if I had the answers. And for a while, I just pretended. I answered the questions as if I knew, even though I didn’t.

But the worst was when I’d hear Mom cry herself to sleep. I’d lie awake and stare up at the blank white wall and remember how May used to cast fairy spells when we were little to make it better.

When Aunt Amy dropped me off at Dad’s tonight, I thought about how he’s the only one from our used-to-be-normal family who hasn’t left me. I wanted to do something nice for him, so I went into his bedroom and brought him some apples. I’d cut them up and spread cream cheese and cinnamon on them. This is something Mom would do, and I thought he’d like it. He was listening to baseball. The season is over, so he plays CDs with broadcasts of the greatest Cubs games that he orders online. This is what he does basically always now, when he’s not at work. Maybe it takes him back to the days when he used to play himself. He was really good at it in high school, and then he used to play on a team here just for fun. We loved to go and watch him when we were kids. I remember the smell of the first sweet summer grass, and the big lights that would come on when it started to turn to dusk. If Dad got a hit, we’d jump up in the stands and scream for him.

When I gave him the plate of apples, he smiled. I couldn’t tell if his eyes were teary or if it was just the light. Sometimes the light is like that. He turned the game to half volume and said, “You doing okay?”

He was wearing his nightshirt, the one that May and I made him for Father’s Day one year. It says We love you, Dad in puff paint, with a small and an even smaller handprint, side by side, on the front of it.

“Yeah, Dad.”

Then he said, “Who is it that you’re always talking to on the phone? Is it a boy?”

“Yeah. Don’t worry. He’s nice.”

“Is he your boyfriend?” Dad asked.

I shrugged. “Yeah,” I said. I would never have told Aunt Amy. But I figured there was no point in lying to Dad about it. Maybe he’d think it was a sign that I was well adjusted or something.

“What’s his name?” Dad asked.

“Sky.”

“What kind of a name is Sky? That’s like naming your kid Grass,” he teased.

“No it’s not. The sky is not at all like the grass!” I laughed.

Then Dad got more serious. “Well, the point is, you know what boys your age are after, don’t you? One thing. That’s all they think of, night and day.”

“Dad, it’s not like that.”

“It’s always like that,” he said, only half kidding.

I tried to tell him that he doesn’t know and that boys are different now, different from when he was a boy, but in my heart, I didn’t mind if Sky was thinking about having sex with me.

Finally Dad said, “Laurel, I understand why you haven’t brought your new friends over here. I know that it’s hard, and I know your old man isn’t much to brag about, either, these days. But if you are going to be hanging out with a boy, I’d like to meet him.”

I didn’t want to bring Sky to our house, but it made me sad to hear Dad say that he thought he wasn’t much to brag about, so I said, “All right.”

“And how about those girlfriends you’re always with? They’re not a bunch of rabble-rousers, are they?” He raised his eyebrows, trying to make a joke of it.

“No, Dad.” I tried to laugh. Then I took a deep breath and asked, “When do you think Mom is going to come back?”

He sighed and looked at me. “I don’t know, Laurel.”

“I wish she hadn’t left,” I blurted out.

“I know.” He frowned. “I know there are things you need a woman to talk about. But at least you have your aunt for now.”

“Aunt Amy doesn’t know those things, I don’t think. I think you should tell Mom she should come home.” I looked at him, waiting.

I wondered if he was mad at her still, for moving into that stupid apartment when she did, and then for leaving us again. I saw him start to tip over with pain, and I regretted saying anything. He sighed the kind of sigh that makes you wonder how he ever got that much air into his lungs to let out, and I understood that he couldn’t help Mom being gone any more than I could.

Where Dad grew up, life made sense. His parents still live on their same farm in Iowa where he used to wake up at the crack of dawn to do the chores. He always said he loved the smell of alfalfa in the morning. When he was twenty-one, he rode away on his motorcycle, stopping in different towns and picking up odd jobs, mostly in construction, then moving on when he was ready. He said that he thought that the world might have more in store, and he’d gone out to find it. But mostly he had loved to tell how it all changed the day he met Mom. How he’d met her and understood, suddenly, why loving somebody and building a family could be enough.

I think I might have been starting to show tears without meaning to, because Dad leaned over and gave me a knuckle-rub on the head, which meant the conversation was over. It’s more talking than we ever do these days, anyway.

I remembered then how Dad would sing me and May a lullaby at night, after he’d cleaned himself up from work, and I could smell the spicy cologne still on his cheeks. He’d sing:

“This land is your land, this land is my land

From California, to the New York Island

From the redwood forest, to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me.”

When he’d sing that song, each place was like a mystery that I would one day discover. It made me feel the world was huge and sparkling and full of things to explore. And I belonged in it, with him and Mom and May. And now, Mom is actually all the way in California. And May is nowhere.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Jim Morrison,

At Fallfest, there is a band that plays your songs. Everyone crowds into a park near the foot of the mountains the weekend right after Thanksgiving. When May and I were kids, we would get excited for it every year. There are tents with crafts, and booths with Indian fry bread and roasted chiles, and booths with ladies selling dried red corn for decoration and pies. But once it gets dark and colder, all anyone wants is the music. Moms and dads and kids and teenagers, too, all head for the stage. Everyone puts on their jackets and dances.

Mom and Dad used to swing dance on the dirt dance floor. They were the best. Everyone would watch them, spinning and lifting. May and I would be on the side, with the Thanksgiving wreaths we made at the craft booth, licking the powdered sugar from the fry bread off our fingers. Mom laughed like a little girl as Dad threw her in the air. It was almost time for the winter to come, but we forgot about our cold toes and our frozen fingers, because we could see what it looked like when they looked like love. We could imagine the story of them, how it was when they met, how it had happened that they made our family. We were proud that they were our parents.

Last year May really wanted to go to Fallfest again, so just the two of us went together. It was the second fall after Mom and Dad had split up. We walked around and ate fry bread, and when the dancing time of night came, we went over to the stage. I stood on the side and watched as May danced with everything in her body, twirling alone in the middle of the floor. It reminded me of when we were kids and how if there was a fight, she’d dance around the living room, using all of the power she had in her to make things better.

But after the first song was over, she said, “Let’s get out of here.”

We were about to leave, and that’s when he walked up. He was wearing a heavy flannel shirt, and he had a cigarette in his mouth and dark hair that hung over his forehead. He looked old to me. May told me later that he was twenty-four.

“I’m Paul,” he said. “You looked amazing out there.” He held out his hand to May, and I saw the dirt under his nails.

May’s cheeks flushed, and the sadness that had been coming off of her was replaced by a smolder. “Thanks,” she said with a slow smile.

Paul flicked his cigarette out and asked her for the next dance. May let him take her hand, and I stood there, watching the two of them together. As he spun her across the dirt stage, May giggled.

When it was over, he asked for her number. She said, “You’ll have to give me yours. I don’t have a cell yet, and you can’t call me at either of my parents’.” So he gave it to her, and he kissed her hand and made her promise not to lose it.

After that night, May started coming into my room when she got home from sneaking out and telling me things about Paul, who she had started seeing in secret. I remember once she lay down on my bed and whispered excitedly, “You wouldn’t believe the stuff he says to me, Laurel.”

“What does he say?”

She grinned and said, “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

“Do you kiss him?” I asked.

“Yeah.”

“What’s it like?”

“Like being above the earth.” She smiled like the secrets she had were enough to live off of. “He got me this.” She pulled a thin gold chain out from underneath her shirt. It had a charm that said May in cursive writing. A heart dangled beneath the Y. I thought that it was funny that Paul with his rugged boots and his calloused hands had picked out a necklace like that.

I wasn’t sure how I felt about her kissing Paul. I always imagined that May would have a boyfriend who looked like River Phoenix, but Paul didn’t look anything like that. It scared me a little bit to think of them together, but I’d been there when they met, and the secret of him tied May and me together. She was opening the door to her new world, just a crack, and I wanted to be in it with her. So when she started to take me with her soon after that, to the movie nights where she’d meet him, it didn’t matter if deep down there was something wrong. I would have followed her anywhere.

This year I went to Fallfest with Sky and my friends. I kept seeing May dancing alone in the middle of the floor, and then giggling with Paul, and for a while I couldn’t shake the anxious sinking feeling I had. But then, when the country swing music was over, the band that covers you came on, last in the night. When they started playing “Light My Fire,” it made me feel like the world wasn’t tired. Like it was just starting to spin, faster and faster. Like there was a new beginning. We all danced like we were trying to get our feet to float off the earth. Tristan bounced up and down and shouted with the lyrics, and Kristen shook her long hair. Natalie and Hannah held hands and spun until they fell down on top of each other laughing. When I turned to Sky and kissed him in the middle of the music, I felt like I was holding a match. And I could strike it. Strike it on the trees holding on to their shining brown leaves. Strike it on a star.

After Fallfest, Sky drove me home. As we were sitting in his truck outside, I remembered Dad telling me he wanted to meet Sky. I thought maybe I could get it out of the way, so I asked Sky if he wanted to come in. “Sure,” he said, and followed me up to the front door. My heart started beating fast. It would be the first time that he’d been in my house. It would be the first time that anyone had been in our house in a while, except for me and Dad and once in a while Aunt Amy.

I opened the front door, and we stood there, in the half-dark living room. I realized it was pretty late. Almost ten o’clock. Maybe Dad was already asleep. “Well, this is it,” I said, and flipped on a light. “My house.” Sky standing there made me notice everything again. The dried wildflowers in the ceramic vase. Mom’s painting of the sunset over the mesa that Dad had never taken down. The family picture on the out-of-tune piano. I wondered how it all looked through Sky’s eyes. I wondered if he noticed May in the photo. Even though we’ve been together for a month now, I still don’t know where he went to school before West Mesa, or what happened there, or how he knew my sister. I guess I’m scared to ask.

Just then, Dad came out of his room in his red bathrobe. “Hi, Daddy,” I said. “This is Sky.”

Sky shook his hand and said, “Hello, sir.”

Dad looked at Sky suspiciously and nodded. “How was Fallfest?” he asked.

“It was good,” I said. “We danced.”

Dad smiled a small smile. “That’s nice,” he said.

It seemed too much suddenly, standing there in the quiet house. So I said, “Dad, we’re going to go on a walk.”

Dad frowned, but he nodded. “Get your coat.” Then he kissed my head good night.

When we went out, I was happy to be with Sky in the night air. It was cold in the clean way, in the making-stars-clear way. It smelled like burning leaves. There were pumpkins that never got carved sitting quietly under people’s porch lights. Sky took my fingers and blew hot breath on them, and then wrapped them up in his hands. He said, “Your dad seems nice.”

“Yeah, but I think he’s really sad. He and my mom split up a couple years ago. And then after, you know, May … my mom left for a ranch in California.” I paused. “I guess I’m kind of mad at her, you know? It’s like, it’s not truly fair. Why should she be the only one to get to go away? As if taking care of horses could change anything. It’s supposed to be clearing her head. But I wish she would come home.”

I missed her a lot right then. For some reason, I thought of her in her teddy bear pajamas, making Eggos for May and me in the morning. How she put a drop of syrup in each square. It felt funny to say it out loud—I’m mad at Mom. But I am.

Sky nodded. “My dad left us, too, a few years ago. Just walked out. I was so mad at him, I didn’t know what to do. It’s like he left me alone to take care of my mom. And after he went, she got worse. Things were always a little bit hard for her. But now, sometimes it’s like she’s not living in the same reality as everyone else. It’s not her fault she’s like that … I just wish I could make it better. But I can’t.”

It was a big deal that Sky was talking to me about this. I wanted to think of something to help. “Have you … Has she seen a doctor or anything? Maybe there’s medicine that could help?” I suggested.

“I’ve tried. Every time I bring it up, she says that there’s nothing wrong with her.”

I could feel him getting tougher on the outside. I took his other hand so that he’d know I was there, which made it hard to walk. He seemed like he wasn’t sure if he wanted to take the hands away from me or not.

We walked in quiet for a while, until we got into a nearby neighborhood where the houses start to get bigger. We passed by the golf course, and Sky asked, “Do you ever jump the fence?”

I hadn’t yet, but it seemed like a good time to start. I smiled and looked at him over my shoulder and started climbing up. My tights got stuck on the wire at the top, the part above my thigh, and Sky had to pry them loose. He followed me over the fence onto the damp brown November grass. The fall geese that had settled there for the night just kept standing about, seeming not to mind us.

I had taken Sky’s hands again, and since I had them, I said, “Spin with me.” I think that’s the kind of thing that boys like to do but won’t do unless a girl asks them to. We spun and spun and spun until we fell down in a heap, laughing. But for some reason, on the perfect cold night grass next to the geese, my laugh just turned to crying.

“What’s wrong?” Sky asked. I didn’t know how to explain it. I didn’t know where to start. Sky held me against his chest, which made me push harder away from him into whatever the crying was for. But when I got quiet, I was glad to be with him. I didn’t say anything for a while. Neither did he, but it was like we both knew what it meant to be there.

When we got back to my house, Sky tiptoed into my room with me. We sat on my half of the disassembled bunk bed that got split apart when May started high school and moved into her own room. I’d never really put up posters or pictures on the wall the way May had done in her new room, so it looked pretty much the same as it had when we were kids. Pink walls, gauzy curtains, dried flower crowns draped over dusty stuffed animals that looked out from a hammock in the corner, wands made of ribbons peeking out from the top of a pencil holder. I felt self-conscious and flipped off the lights, and plastic glow-in-the-dark stars shone down on us.

Sky and I started kissing. We kept kissing, and kissing, and his hands were everywhere on me, and everything inside of me was hot, like pavement on a summer night. A burning you can’t stop. When Sky paused and asked, “Are you okay?” I noticed how fast I was breathing. I remembered, in a flash, what it was like those nights at the movies, and I thought for a moment that he could see it. That he knew, somehow, all of the things that I’d let happen. That he could tell. But then I saw him just staring at me, worried. “Laurel?”

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m good. It’s just … intense.”

He’d never have to know, I thought. I could be new. I would be May, the May who was brave and magical. I wouldn’t be me, the one who let everything go wrong. I focused so hard, until Sky was all that I could see. And then I got this feeling that I needed to be so much closer to his body. I wanted our skin to stop keeping us apart. So I kissed him harder, and he kissed me harder, and my clothes came partway off, and he touched me everywhere. It was then that all of the sad things inside of me turned into hungry things.

Finally, after we’d made out and gotten quiet and made out again, when the littlest bit of gray light started to leak in through the curtains, Sky tucked me under the blankets and started to sneak out of the house through the window, so Dad wouldn’t hear him.

“Sky?” I said as he was leaving. I was half-asleep, but I didn’t want him to go. As the night air rushed into the room, it seemed like it could swallow him up and take him from me.

He turned back. “Yeah?”

“You’ll still be here, right? Tomorrow?”

He smiled and kissed my forehead. “No,” he said, “I’ll be at home.”

“But, I mean, you won’t leave me, right?”

“Right.”

When I woke up today to the memory of Sky’s body, all of the sad things in me were still hungry. They started to take everything in—the rain streaking in the sky, the spill of light on the table, the tiniest drops of water clinging to a pine needle on a tree outside my window. Maybe that’s what being in love is. You just keep filling up, never getting fuller, only brighter.

I looked you up, and I found out where the name of your band came from—from this quote, written by a poet named Blake: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” I’ve been thinking about that. About what it means to see the endlessness of each moment, of each piece of it. I want to be cleansed—I want to burn away all of the bad memories and everything bad inside of me. And maybe that’s what being in love does. So that a life, a person, a moment you need to keep, stays with you into infinity. May smiling back at me. The two of us as little girls at Fallfest, with parents who danced. Your song playing into eternity. The night leaves on the cottonwood trees catching the white lights. And every little star that burns hotter than we could know.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Janis Joplin,

Kristen’s parents have money, but she drives a super old Volvo anyway, because she thinks it’s cool. She has a bumper sticker on the back of it that says I’M NOT TALKING TO MYSELF … I’M TALKING TO JANIS JOPLIN. When she and Natalie and I were driving to Garcia’s Drive-In during lunch on Friday (Kristen never ditches classes, only lunch, because she’s a good student and keeping her grades up for college applications), of course we were listening to you. Since Kristen loves you so much, she knows all of your songs, not just the most popular ones. You were singing “Half Moon,” and Kristen turned to Natalie and said, “Did you know that Janis had women lovers, too?” Natalie shook her head no. Kristen continued, saying, “She could have been singing about a woman when she sang this,” as you crooned, Your love brings life to me.

Natalie looked off and said, “That’s cool,” trying to sound like she didn’t care. But by the way her face spread with a little smile, I could tell she did think it was really cool. I think Kristen was trying to make Natalie feel like she knew about her and Hannah. Like it was okay.

Hannah got another boyfriend. She has two right now, counting Kasey and the new one, whose name is Neung. She met Neung at Japanese Kitchen, where he’s a busboy and she’s a hostess. Yesterday, we went to his house, Hannah and Natalie and me. It was Sunday, and after we opened the fourth day of Aunt Amy’s advent calendar, I’d asked her if I could go to Dad’s early in the day, so that really I could go and hang out with Natalie and Hannah.

Before we left Natalie’s, Hannah kept trying on new shirts and asking Natalie if she looked fat, and Natalie was getting mad and saying, “Of course you don’t.” Hannah put on a lot of makeup, so she had these crimson lips, darker than bloodred against her pale freckled skin. She looked like someone who was beautiful but trying to show how she hurt.

We walked to Neung’s from Natalie’s, and it was really far. It’s getting cold now even when it’s still sunny, but Hannah didn’t wear enough clothes, so the whole way there she was shivering. Natalie was putting her arms around her to keep her warm, and Hannah was talking about Neung and how his skin is so smooth that when she touches it, she feels like the world will never end. And how he used to be a gangster. Natalie said she didn’t want Hannah going over there alone, which is why we went along. I was glad, too, because I didn’t want her going alone, either. I didn’t know what might happen to her.

Neung lives in this tiny house with his whole family, his mother and his father and his uncle and his grandfather and his brother and his sister and his sister’s son. Before we got there, all the way down the block, we could smell the hot peppers cooking. His mom and sister were cooking them on the grill outside. They must have been the hottest peppers in the world. As we got closer and closer, our eyes started to burn so badly from the smoke that by the time we made it to Neung’s, our faces were covered in tears, and Hannah’s mascara had streamed down her cheeks.

We played outside with Neung’s little nephew, wiping away pepper tears the whole time. Neung was nice around us, and he picked up his little nephew and spun him like an airplane. He laughed at our chile tears and called us güeras, which means “white girls” in Spanish. He did this even though he’s Vietnamese and Natalie’s Mexican, so it didn’t make that much sense.

Then Neung drove us to the 7-Eleven to get Slurpees and cigarettes. Once we were away from his family, Neung started touching Hannah a lot, and calling her baby girl and putting his hand in the back pocket of her jeans when they were walking, which made Natalie roll her eyes at me. When we got back to Neung’s, we sat on the sidewalk and drank the Slurpees, and they all smoked the cigarettes. (I didn’t smoke any, because I don’t actually like them that much. I thought I’d get used to the taste, but I haven’t.) We all laughed about our chattering blue lips. Then it was getting to be nighttime, and Neung said he wanted to be alone with Hannah. So they went inside, and Natalie and I sat on the steps, waiting.

I kept looking up at the moon. It was so bright. Not yet a whole circle, but trying to be. Like it wished so much to be round and full and perfect. I thought about the nights when May would leave to go away with Paul, and I started to worry for Hannah. Natalie was quiet, building a little house out of twigs and smoking a lot of cigarettes. Everything I said seemed to come out of my mouth and fall to the ground in slow motion. When I ran out of things to say, I said, “You love her, huh?” And Natalie kind of nodded, and then she started crying. Really, really crying. I put my arms around her.