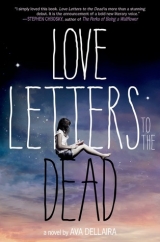

Текст книги "Love Letters to the Dead"

Автор книги: Ava Dellaira

Жанр:

Подростковая литература

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

I nod. I am a little sad that it won’t be just me and May, but the most important thing is that she let me in.

When we stop at the light before the movie theater, she tucks her hair behind her ears, and then ruffles it up, and then tucks it again. And then she puts on lipstick.

She turns to me. Her lips look grown-up, like the ones she cuts out of her magazines for collages, but her face is soft. She says, “Do I look okay?” I say she looks beautiful. I haven’t ever seen anyone look like that before. Not even her.

When we get there, only a couple of people are left in the ticket line, and there is Paul with another man standing off to the side. Paul has on the same plaid shirt he wore the only other time I’ve seen him, at Fallfest. He looks a little cleaner than the other guy, who has jeans with holes and a shirt that says BACK IN MY DAY, WE HAD NINE PLANETS. When May sees Paul, she waves a little wave. She walks up slowly, her hair swinging behind her. I follow. When we get close, they don’t touch, but from her look, I can tell they will.

I am playing with the frog snap on my shirt. I am snapping it on and off.

May talks in a grown-up voice and says, “Laurel, you remember Paul, and this is his friend Billy.”

Paul says, “Hey, kid,” which is what Carl and Mark, the neighbor boys, call me, and ruffles my hair. I don’t want him to.

May says, “Paul and I are going to go somewhere, okay? Billy will take you to the movie.”

I don’t want to go see Aladdin with Billy, whose hair is long and dirty. I want to go with May. But I say, “Okay.”

May says to Paul, “He’ll take good care of her?”

And Paul says, “Of course he will.”

May looks at Billy and says, “You will?”

“You bet.”

May sounds very in charge when she tells him, “You are going to take her to Aladdin. Don’t try to sneak her into something R-rated.” He says he won’t, but I start to feel like maybe he will. I am still snapping the frog on and off my shirt, on and off. The frog is my favorite. I am looking down at the shadows of the trees on the sidewalk.

May gives Billy Dad’s ten dollars. She tells Billy that we love Sour Patch Kids. She makes him promise to get me some. And then May kisses me on the head and says have fun, and she says, “I’ll be back right after the movie’s over.” And she walks off with Paul. I watch the car leave, taking May away, and I don’t want it to go.

Billy says, “So what do you want to do?” My throat gets dry. I squeeze the frog in my hands. I try to swallow. I mean to ask if we are going to the movie, but I don’t know if I say it out loud or not. I find the cherry Jolly Rancher in my pocket that I’d saved from the Village Inn where we had dinner that night. I start sucking on it, but somehow my mouth is still just as dry.

Billy says, “Do you talk?”

I shrug.

He says he forgot something in his car. He says come on. So I follow him over the long stretch of blacktop. The world is dizzy, like something happened to the earth under my feet. We get to a car at the edge of everything. He opens the door. He says get in. I don’t want to. I just stand there. My mouth is really dry still. He says it again: “Get in.” He sounds angry this time. It scares me, so I do what he says. He leans really close to me. I can feel his breath, which smells like something too sweet and wrong and hot and, now that I think of it, I guess maybe like booze.

The sky is dark already, and I wish that it wasn’t. Billy says that he can tell I’m too old for a kid’s movie. He asks if I want to go somewhere instead. “Ice cream?” he asks. I shake my head no. “Have it your way,” he says, but he drives off anyway, and then he parks in an empty lot nearby.

The next thing I remember is that his hand is in my rain forest shirt. Underneath, I mean. I swallow the Jolly Rancher whole, and it hurts stuck in my throat, so I think I can’t breathe. The frog is unsnapped, I remember, because I remember it in my hand, the plastic of it, and I remember thinking about the frog and wishing I could put it back on my shirt, because that is its home. Only now I never can. I would never be able to wear that shirt another time, and it wouldn’t be safe for the frog. He would always be lost.

I try not to think of Billy’s hand or where it is, so I just focus on trying to breathe. His hair is greasy, and his body is long. Too long. He tells me I am pretty.

I wonder if he means pretty like May is. I think of May with Paul and wonder if this is what is happening, if this is what’s supposed to happen. Deep down I know it’s not right, but I pretend, pretend I am like May with her pink cheeks and her lips that look like close-up pictures in a magazine.

I keep thinking she is about to come back. I can hear cars in the distance like ocean sounds. I am listening hard to engines rolling by like waves. Like the silence that isn’t silence when you put a shell to your ear. And then sometimes something gets louder, and I hear a car, and I think it is getting closer. And I think it is May. She is about to come back. And it will stop. As soon as May comes, it will stop. But all the getting closer cars turn away. They go back on the highway. Maybe they are going to California.

When he is done doing that stuff, Billy drops me off outside the movie theater. The sign shines with the movie times. It still feels like there is a sliver of the Jolly Rancher stuck in the back of my throat. I am sitting there on the sidewalk, trying to concentrate on something. I look at the pale scattered stars in the sky, and then at the concrete and the pieces of glass glinting in it, like brighter stars. And then I read the numbers on the movie sign, over and over, trying to figure out what time it is so I could know when my sister would come.

People must be coming out of the movie, because there are voices around. When May jumps out of the silver car and it pulls away, everything is real again. She looks worried. She says, “Laurel! Why are you alone? Where’s Billy?” I shrug. I tell her that he was late for something and had to go. “Were you waiting long?” she asks.

“No, not that much. He just left.”

She tilts a little on her kitten heel, and when she thinks I am okay, she giggles like something good happened, but almost too much, like too happily. She says that Paul likes HardCore Cider, which is even better than the cider that we used to have at the apple farms in the fall.

When we are back in the Camry, I smile at her. And even though I don’t feel well, I think maybe the world is back to normal again, because now we are in the car driving home, and May is my sister. I don’t say what happened or anything about Billy. I know that it’s not what was supposed to happen, and if May knew, she would always be sad. Too sad. She would go away from me. I didn’t want that. And if only I’d never said anything, maybe she’d still be here.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Kurt,

The day after the party was Sunday. I stayed in bed as long as I possibly could without Dad getting worried, and when I got up, I felt like I was walking through the thickest fog, like the kind that comes off of dry ice. I snuck into the bathroom and washed off the party makeup that was giving me black eyes.

Evan and Sky and May and the movies—it was all this frozen blur. I saw Jason’s face in my mind. I called Natalie and Hannah a bunch of times, but neither of them answered. So I asked Dad to drop me off at Natalie’s and said that I’d walk to Aunt Amy’s from there.

When Dad pulled up and parked in front of her house, he hugged me and held on for a long time, which I thought was strange.

He looked at me and said, “Are you okay today?”

I worried that somehow he could see through me. “Yeah,” I said. “Love you,” and I hurried out of the car before he could ask me anything else.

When nobody answered the door, I went around to the back and found Natalie lying on the trampoline, crying. Hannah was sitting on the edge of it, her knees curled in a ball against her chest.

I stood toward the edge of the yard, listening. Natalie asked, through sobs, “Do you even love me?”

“Of course,” Hannah said flatly. “But people won’t understand. They’ll take it apart and turn it into something else.”

Natalie looked crushed. “Love isn’t a secret. I can’t act like it doesn’t count. It counts, doesn’t it?” Her voice went up at the end.

“You don’t know my brother,” Hannah said. “He flipped out, and he’ll flip out even more if he finds out we’re, like, together.” I couldn’t help thinking of the look in Jason’s eyes. The kind of anger that could make anyone turn small.

“Are we even? You’re with Kasey and whatever other guys. Like I don’t even matter.”

“That’s not true,” Hannah said. “Of course you matter.” Then she said, more softly, “It’s just better if I’m not around so much,” and she got up. “I’ve got to get back. Jason thinks I’m at the library.”

As Hannah turned around to walk out, she saw me standing there. “Hey. What happened to you last night? You opened the door on us, and then you just disappeared after that?”

“I know. I, um … I’m sorry.” I knew that I should tell them what happened with Evan. I knew that I should. But this horrible panicky feeling was all over me, and my voice felt choked.

“Laurel? Hello? Where did you go last night?”

“Sky took me home.”

“Oh, great. So you open the door on us and then go off with Sky? Well, FYI, things are pretty much ruined now. Do you even care?”

“No, I mean, yeah, I…” May was falling off the bridge. I was falling with her. It was all my fault, all of it.

“Forget it,” Hannah said. “It’s done now.”

She hopped over the low wall. Natalie watched her go, but Hannah never turned around to look back. Natalie cried harder. I tried to go and sit by her, but she curled into a ball.

“I’m sorry,” I said before I got up.

On the walk to Aunt Amy’s, I put your voice on my headphones and listened to you singing “Lithium.” I shouted along with you, “I’m not gonna crack,” and it’s exactly—not just the words, but how your voice sounded singing them—how I felt.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Kurt,

When I got to Aunt Amy’s, she wasn’t home yet. She must have been out with the Jesus Man, I figured, who came into town last week. I lay on the couch and closed my eyes. I guess I fell asleep, because when Aunt Amy came in the door, she woke me up.

I asked her how her week was, trying to tell if she was happy now that the Jesus Man was back, but she just said, “It was good. How was yours?”

“Fine,” I lied, and then she put on 60 Minutes, which is pretty much the only show she likes other than Mister Ed. That little ticking stopwatch must be almost as old as he is. The episode was about free divers. They dive hundreds of feet underwater without any oxygen tanks, and if they’re not careful, they can black out. I got sort of sucked into it, imagining what it would be like, trying to swim up from so far down with no air.

When the show was over, Aunt Amy called me to come eat. She’d made pancakes and bacon. That was May’s favorite—breakfast-for-dinner night. I sat at the kitchen table and waited for the prayer. But instead, Aunt Amy just looked at me and asked, “Are you all right?”

“Yeah,” I said. I wondered if I really looked that bad.

Then she said, “I know you must be thinking of your sister today. Should we pray for her?”

It hit me in a flash. It was a year ago today that May died. How could I have forgotten? I felt awful.

“Um, yeah. Can you do it?” I asked.

She squeezed my hand and then bowed her head and said, “Dear Lord, we ask that you keep May, our beloved sister, daughter, and niece, with you in heaven’s care. We thank you for the blessing of the time we shared with her. We also pray for her sister, Laurel, who she’s left on this earth, that you cherish her heart and stay by her side in her time of grief. In Jesus’ name, Amen.”

When she finished, Aunt Amy looked up at me with teary eyes. I didn’t know what to say. I choked down a bite of my pancake and wanted to throw up.

After dinner, I tried to disappear into my room, except a couple of minutes later Aunt Amy came in to bring me the phone. It was Mom. Since we got in that fight last month, our few conversations had been about five seconds long.

“Hi, honey.”

“Hi.”

“How are you tonight?”

“Okay, I guess.” I sat down on my bed and pulled the rose quilt around me and stared at the empty, pale pink walls.

“I know it feels like I’m far away, but I want you to know, my heart is with you today.”

I couldn’t swallow it. “That’s nice, Mom, but it doesn’t really make anything easier.”

The other end of the line was quiet, until Mom said, “I’m sorry, Laurel. I just thought … I thought you’d be better off without my grief to deal with. I didn’t know how to be strong for you after May died. I thought it would be worse, your seeing me cry all the time.”

The words fell out of my mouth before I could think about it. “Nothing is worse than when someone who’s supposed to love you just leaves.”

The phone line filled with static that sounded like the ocean, both of us crying in our separate corners of the planet.

“Maybe you think it’s my fault. Maybe that’s why you left,” I finally said.

“Laurel, it’s not your fault. Of course it’s not your fault.”

“Well, maybe it is. I should have never told her…”

“Told her what?”

The room was spinning and spinning now, and I was breathing too fast. “I don’t know. I have to go.”

I let the phone fall to the floor. I couldn’t stop crying. Everything was flooding in, everything too fast. Hannah in her bra at Blake’s, her face-painted bruise, Natalie’s chipped tooth, don’t tell, the door open with them kissing and it’s my fault, I didn’t save them, I couldn’t save them, I couldn’t save her. The soap in the shower that will never get it clean enough and the frog in the back of my drawer, I just left him there, and your poster torn to shreds and the bunk beds taken apart, I just want to climb the ladder and lie by May so it can be okay. Sky walking away, driving away, everyone away, and May rolling away from the car, how it was going to hit her, how she yelled at me when I tried to stop her, the car going too fast down the road, too fast, and now Mark the neighbor boy will never love me, the river flooding my whole head, the guy’s hand reaching toward me, his hand on me, his hand under my shirt, sticky thighs on his seats, but just be like May, be pretty like her, be brave, this is what it’s supposed to be, this is the world now, wake up, his hand on me, how it felt, and the night hot and sticky and sticking to me and your voice I’m not gonna crack—

Dear Kurt,

After the first night at the movies, I would watch Aladdin at home on DVD. I watched it over and over. Whenever I’d remember things I didn’t want to remember, I would put it on so that I could replace Billy with the movie I was supposed to have seen that night, how Aladdin ran around the city, stealing things, saying, “One jump ahead of the slowpokes.” How he and the princess rode on the carpet, singing, “A whole new world…” I would practice being like them, just soaring over everything.

The next time May took me to the movies after the first time, she walked into my room in Mom’s apartment and asked, “Do you want to go to the movies tonight?” with a wink. At Mom’s she could have just gone off by herself. When I used to ask her to take me wherever she was going, she’d say I was too young. But now she wanted me with her. I didn’t know what to say. I felt like if I let her leave without me, I would never get her back. I told myself what happened with Billy wasn’t that bad. I told myself that’s what people do. If I pretended it never happened, I thought maybe it never would have.

So Friday nights became movie nights. It started late that fall after she met Paul and lasted into the spring. We’d go after the Village Inn dinners, with Mom’s or Dad’s ten dollars. When we’d be in the car on the way, May’s lips would get dark as she put her lipstick on. She’d smile and pass it to me and say, “Do you want some?” I’d watch my lips turn dark, too, as I smoothed the crayon-tasting color over my mouth. It was like make-believe. I thought if I stayed close enough to May, the power of her would rub off. So I’d try to use the crimson as an eraser, to take away the feeling of being scared. For both of us. We’d listen to songs and sing loud. I would ignore the sick feeling in my stomach. I would try to be happy. I was with my sister. She liked me, and we were friends again.

And sometimes, May and I really did go to the movies. Sometimes there was no Paul or Billy to ruin everything, and we’d buy Sour Patch Kids and sit in the back of the theater and whisper.

But other nights, when we’d walk up and I’d see Billy standing outside with Paul, my heart would go sick with dread. May and Paul would go off in Paul’s car, and once they were gone, Billy and I would get into his car, parked on the field of blacktop, and he’d drive off somewhere. I got good at it after a while, riding on the carpet above the earth, or riding with the car engines to the ocean.

Billy would start to touch me and say, “I can’t help it. You cast a spell on me.” I wondered if I did cast a spell on him by accident. What if somehow I made him do it, by wishing to be like May, by wishing that she’d take me with her when she used to leave at night?

Sometimes Billy would hang around with me outside of the theater, waiting for May and Paul to come back, so that I wouldn’t look like I was always alone, I guess. When May would ask me if I liked the movie, I would rush past my answer, asking her for stories instead, imagining parties she’d been to with the music so loud that it got into your heartbeat. A lot of times, her breath would smell like alcohol, or her eyes would be glazed over. But she was always smiling, so I thought she was happy. I wanted her to be happy.

When I would come home and get undressed at night, I pretended like I was peeling off my skin. Taking away the dirty parts so I would be new again. Soon there weren’t many clothes left to wear anymore, and I kept asking Mom for new shirts. I felt bad about it because we weren’t supposed to get that many new shirts, on account of not having a lot of money, and she kept asking what about your old shirts, and I said that in middle school they didn’t wear rain forests or deserts or even tie-dye. And I didn’t tell her that they were all thrown away, balled up in the trash of the McDonald’s near the apartment.

But the frog I couldn’t throw out. I saved him, in the back of my secret drawer. He was the only one who knew what happened. And the frog was my favorite. The shirt he used to live on was gone now, but he still had the bottom half of a snap on his belly to remind him of the home he got broken off from.

The night May died was after a movie night. Things were different with Billy that time. “You’re getting to be a big girl,” he had said. “Let’s try what big girls do.” It used to be that he would just want to touch me places. And then he’d want me to watch while he did something. But this night, he wanted me to do it. He said I couldn’t stop until it was done. I kept waiting for it to be done, but it seemed like it never would be. I couldn’t go anywhere else in my mind. All I could see was that, waiting for it to be over.

After, I was waiting outside the theater. Paul’s car pulled up, and May got out. Her breath smelled like liquor, and she looked like she had been crying. But when we got in the Camry, she tried her best to smile and turned up the music. She said let’s not go home yet. She said let’s go to our spot. And when I reached out to touch her arm, she stopped singing and turned to me.

She said, “Laurel, don’t ever let anything bad happen to you, okay?” She looked back at the road and said, “Don’t be like me. I want you to be better, okay?”

I swallowed and nodded. I didn’t know what to say. When we got to the bridge and crawled out into the middle, I looked at her. “May?” I said. “I’m scared.” I wanted her back.

“What are you scared of?” she asked.

“I—I don’t know.”

“Here,” May said. “Do you want to make a spell? Go get one of those flowers.”

I crawled across the bridge, and pulled one of the little blue flowers out of its crack, and brought it back to her. May pulled its petals off, one by one, and held them in her hand. “Beem-am-boom-am-witches-be-gone!” her voice slurred as she flicked her fingers, scattering the petals to the wind. She laughed a little and looked at me like she was searching for something.

I tried to smile back. But then I blurted out, “Billy says that I am going to be pretty like you.”

“What do you mean? When does he say that?”

“Just, just when you leave sometimes. When he—he takes me in his car with him.”

I could see her face change. She was scared. It made me even more terrified. She started crying. She grabbed on to me and held me too tight. “What happened, Laurel?” she whispered. “What did he do?”

“No. Never mind,” I said, desperate to push it away. “It’s okay.” I was grasping for anything to make her stop crying. I just wanted her to be magical again and protect me from everything. “May, remember? Remember when you could fly?”

She looked at me with a little smile. “Yeah,” she said softly. And then she stood up. She started to walk across the track, her arms out like make-believe wings. I kept looking for my voice. I wanted to call her name, but I was somewhere else. Not there, not all the way. And then—it’s like the wind blew her away from me. When I screamed, “May!” it was too late. She didn’t hear me. She was gone. She was gone already. “May! May!” I screamed her name over and over, but my voice was drowned out by the river.

When she went somewhere I couldn’t follow, I sat frozen. Waiting for her to come back. To come and get me. I heard the river like the sound of distant traffic, like the sound of the far-off ocean, same as ever. But no cars came. The road was as empty as a night sky without starlight.

Dear Kurt,

Aunt Amy is snoring now in the next room. After I got off the phone with Mom, she came in, and I was crying and crying. When I finally calmed down, she made me tea and tried to talk to me. I told her that I was just sad tonight and asked if I could go to bed. But I couldn’t actually sleep, so I wrote you letters. And then I didn’t know what else to do. The spring air was coming in through the window. It smelled just like it did the night she died, blossoms in the dark, new weather trying to break through the cold. I couldn’t be alone.

I picked up my phone and saw that I’d missed a call from Sky. I kept almost pressing the button to call back and then taking my finger away. But finally, I let it ring. I told myself there was nothing left to ruin.

It was late, midnight, but he picked up. “Hey,” he answered.

“Hi.”

“I was worried about you.”

“I kind of have to … I’m at my aunt’s and I just … I can’t be here right now. Could you come and get me?”

He paused a moment. “All right.”

So I crawled out the window, shivering in my sweatshirt, and waited for his truck to pull up. When I got in, Sky didn’t really look at me. He was staring straight through the windshield.

“Where do you want to go?”

“The old highway.” Right then, I knew I had to.

“Are you sure?” Sky asked.

I nodded yes.

So we turned onto the road, which I hadn’t been on since, except in my mind. I was breathing way too fast.

When we got by the bridge, I said, “Stop here.” I forced the door handle open and stepped out. I walked toward the edge of the bridge. I kept walking forward. I put one foot on the ledge. I held my arms out. The night was still. No wind. Nothing to push me one way or the other.

I could feel my one foot on the slim line of metal. The balance beams of our childhood. And the other foot still back on the earth.

I saw May walking out, her slender arms reaching out through the air on either side. I saw her fairy wings come out. I saw them trying to flutter to keep her up. To take her back. But I’d broken them. I saw the wings like tissue paper break off and float into the sky as she fell. I saw them falling after her, slowly like leaves. But her body. Her body had density. It was gone before I could hear it splash. Her body that I used to sleep next to. Her body that would steal the covers and roll like a burrito so that I would shiver and then give up and scoot closer, just to get a little warmer. I remembered how she smelled like apples and mint and earth in the summer. I wanted to go with her.

And then I heard Sky. “What the fuck are you doing?”

I pulled my foot off of the ledge. I could feel him grab me.

“Don’t get that close,” he said. “You’re scaring me.”

I heard the sound of the river moving on, as if it hadn’t stolen my sister’s body. I turned to him. And I just talked. Because everything was already lost. “She left me. She’d leave me alone at the movies with this guy who used to do stuff to me. I know she didn’t mean to—but I was so—I’m so mad at her.” I’d said it. I’d said it out loud.

“Laurel,” Sky said, and reached out to me again. “Of course you are. What guy? Who did that?”

“It doesn’t matter now. A friend of Paul’s. And I tried to tell her what happened, and then—she was so upset, and I’m afraid, I’m afraid it killed her.”

“Why would you think that? What happened?” Sky asked.

I told him the whole story. When I was finished, he looked at me and said, “Laurel, it wasn’t your fault.”

“But maybe if I never let it happen in the first place, or maybe if I never said anything, maybe she’d still be here.”

“Stop it,” he said. “You can’t blame yourself. Maybe she’d still be here if she hadn’t been drinking. Or if the wind were blowing a different direction that night. Or if she’d leaned another way. You’ll go crazy thinking like that. She made her own choices. You have to look out for yourself now. That’s the best thing you can do for her. That’s what she’d want for you.”

I looked at his eyes, and it started to sink in. I’d told Sky, and nothing bad was happening. Nothing worse. He was still right there. Just standing in front of me.

“You don’t hate me?”

“No.”

“You’re not scared of me?”

“No. I just want you to know that you don’t have to let that stuff happen to you anymore.”

He put his arms around me, and something burst open. I started to cry. “How could she just leave me here to live without her? I miss her so much. I love her. I want her to grow up and become who she was meant to be. I wanted her to grow up with me.”

Sky let me cry, and when I finished, he led me away from the bridge and opened the door to his truck. “Come on,” he said, “let’s get out of here.”

We got in together, driving the other way on the road. He drove fast but never too fast. Just right the whole time, the way he always had.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Amelia,

Sometimes it feels strange that the sun just goes on rising, as if nothing happened. When I woke up today, the birds were chirping their oblivious chirping, and cars were starting down the block. I’d hardly slept last night after I got home from the bridge, and my eyes would only open into little slits. As I tried to pull myself out of bed, I thought of you for some reason. I thought of you on the tiny island where you might have landed and lived as a castaway.

I imagine what it would have been like, waiting and waiting for someone to come and rescue you. Building fires, making smoke signals that disappeared into the clouds. How long could you have lived there, you with your navigator? Which one of you died first and had to mourn the other?

They’ve found artifacts on Gardner Island, which lies near Howland—the place you meant to land that morning, in the middle of the Pacific between Australia and Hawaii. They found pieces of Plexiglas that matched the kind on the windows of your plane, the heel of a shoe that could have belonged to you, bird bones and turtle bones, the remains of a fire, shards of Coke bottles that seemed as if someone had used them to boil water to drink. And then, most recently, they found four broken pieces of a jar, the shape and size of one used for a cream made to fade freckles in the era when you were alive. Everyone knew that you had freckles you wished you could erase. As I got dressed, I carried the thought of that little jar, left behind as evidence. It seems so vulnerable, compared to your brave face meeting the world.

At school this morning, everyone knew about Natalie and Hannah kissing at the party. I saw Hannah walking down the hall, and one of the soccer boys called out, “Yo, wanna have a threesome?” His friend said, “Four boobies are better than two.” I told them to shut up, and I tried to go over to Hannah, but she turned and rushed the other way.

In English, Natalie kept the hood of her hoodie on all through class, and when the bell rang, she hurried out before I could talk to her.

At lunch, our table was empty. I stood there for a minute, wondering where to go. Finally I went and sat by the fence, like I used to. I remembered watching the leaves fall from the trees at the beginning of the year and stared at the green buds starting to grow back now.

Then Sky walked up and handed me a pack of Nutter Butters. “Here,” he said. “I thought you might want this.”

“Thank you,” I said, and smiled at him. I took it, and he sat down next to me. I gave him half, and we just sat like that, crunching and not saying anything else.

After school, I called Aunt Amy and told her I had a study group and that I would get a ride home after. I stayed in the library alone for as long as I could, thinking about Natalie and Hannah, and thinking about May, and thinking about you on your island. I thought about how I tried so hard to be brave this year. But maybe I’ve been getting it wrong the whole time. Because there’s a difference between the kind of risk that could make you burn away and the kind you took. The kind that makes you show up in the world.

Finally, when it started to get dark out, I walked back to Aunt Amy’s. I took a deep breath and turned the knob to the front door. She was sitting on the couch, waiting for me. She had a kaiser roll sandwich cut in half on a TV tray.