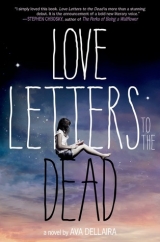

Текст книги "Love Letters to the Dead"

Автор книги: Ava Dellaira

Жанр:

Подростковая литература

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

“Oh yeah? How do you know?”

“By the way you talk. Like when you said that Kurt is so loud because he’s staring the monster in the face, and how you’ve got to fight back.”

Sky smiled a little bit, like he was happy that I’d really been listening.

I pointed ahead. “Oh! Turn left up here.” We’d almost missed my street.

When we parked outside of my house, we were quiet a moment, my breath clutched in my chest. I watched the sequins on my dress catch the glow from the street lamp. And then I looked up at Sky. He reached out and took my face in his hands. “You’re beautiful,” he whispered. I closed my eyes and let him pull me in. It was a perfect first kiss, like a gust of wind that swept through me, taking my breath away and letting me breathe again all at once. A kiss to come alive in.

When Sky finally got out of the car and opened my door, I was longing for more. He was so calm. In control. Unlike me, whose everything was shaking.

“So,” Sky asked with a little smile, “did it turn out the way it was supposed to?”

“Yeah, it did,” I whispered.

“Good,” he said, and kissed me softly on the forehead.

As his truck pulled off, I went inside as quietly as I could, carrying the secret of the night as I tiptoed over the creaking wood floors, past the door of Dad’s room that used to be Mom and Dad’s. Past May’s room. The house felt haunted, like only I understood the way all of our shadows, the ones we’d left, had seeped into the wood and stained it. How the floor and the walls were full of our bodies at certain moments. I went to my dresser and stood in front of the mirror. I unpinned my hair. I wiped away my lipstick onto the back of my hand. I looked at my face until it was only shapes. I kept looking, until something reformed. And I swear I saw May there. Looking back at me. Glowing from her first dance.

I got in bed and played “The Lady in Red” off of her CD. I thought of Sky’s hands pulling me closer. How he had said that I was beautiful. And I knew that he had seen her in me. I skipped back the song again and again until my hand was too tired to move. Before I slept, I felt like I was breathing for both of us. My sister and me.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Amelia,

I think I am going to be you for Halloween, which is coming up in a little less than two weeks. I’m excited about it, so I am getting my costume ready. I don’t want to be a ghost or a stupid sexy cat. I want to be something that I really want to be, and you are like bravery to me.

Halloween is one of my favorite holidays. Christmas and the others can end up making you sad, because you know you should be happy. But on Halloween you get to become anything that you want to be.

I remember the first year Mom and Dad let us go trick or treating alone. I was still seven, and May had just turned ten. She convinced them that double digits meant she was grown-up enough to shepherd me along our block. We ran up to each house, the fairy wings we carried on our backs flapping behind us, ahead of the kids who had their parents in tow. Every time a front door would open, May would put her arm around me, and it felt like she would always protect me. When we got home, our noses were ice-cold, and our paper bags, decorated with cotton ghosts and tissue paper witches, were full. We emptied our candy onto the living room floor to count it up, and Mom brought us hot cider. I remember the feeling of that night so much, because it was like you could be free and safe at once.

I think that this year we are going to a party that Hannah’s college boyfriend, Kasey, is having. I told Sky about it, and I hope he might go, too. It’s been one week since homecoming. I don’t think he wants to have a girlfriend, because of what Kristen said about how he just “has girls” sometimes. I try to remind myself of this so that I don’t scare him off. But to tell the truth, I’ve never liked someone so much. Since the dance, I’ve caught him watching me a few times at lunch. And I watch back. Then yesterday, when I was getting stuff from my locker, I closed the door, and there he was, out of nowhere. My body instantly remembered kissing him. The feeling almost knocked me over.

“What’s up?” he said, just smoothly, the way he does.

“Um…” I was thinking fast. I was not going to say nothing. “It’s almost Halloween.”

“Indeed.”

“What are you going to be?”

Sky laughed. “I usually just put on a white sheet and pass out candy to trick-or-treaters with my mom.”

“Well, we’re going to this one party, because Hannah’s seeing this guy or whatever. It’s a college party, and, I don’t know, you should come…”

“You’re going to a college party?” He sounded vaguely disapproving.

“Yeah.”

“Well, I guess maybe I better. I don’t want you getting into any trouble.” Sky said it like he was mostly teasing, but meant it a tiny bit.

I tried to keep myself from giggling. “I’ll send you the address, you know, in case.”

When I told Natalie and Hannah about this at lunch, they were eating Halloween candy early, and Hannah said, in the middle of a handful of candy corn, “That means he wants to do you.”

Natalie hit her shoulder and said, “Han-nah!”

“What? That doesn’t mean she’s gonna. Laurel’s a good girl, can’t you tell?”

My face got all hot.

Then Hannah said, “Sleepover at my house tomorrow, are you in?”

I was so happy, because the invitation meant that Hannah thinks I “get it,” like she said Natalie does. That now we were real enough friends for me to go to her house. In my head, I started calculating how I’d get permission. I’d still be with Aunt Amy, before I switched to Dad’s on Sunday.

Finally, as a last resort, I decided to call Mom and ask her to tell Aunt Amy that she should let me spend the night at my friend’s house.

“What friend?” she asked.

“Hannah,” I said. “I always hang out with her. My friend Natalie’s going, too. Dad already lets me spend the night with them.”

“What’s Hannah like?” Mom asked.

She could probably hear the shrug in my voice. “I don’t know. She’s just normal.”

“What does ‘normal’ mean?”

“She’s cool and nice. What is this, twenty questions?”

“I just wanted to know a little bit about your life now,” Mom said, sounding hurt. “Who your friends are.”

I felt bad, but I couldn’t help thinking that if she really wanted to know, she’d be here.

It was quiet for a moment, and then Mom laughed a little. “Do you remember when we used to play that game with your sister in the car on the way home from school?”

She meant twenty questions. “Yeah,” I said. I couldn’t help laughing a little, too. May was great at that game, like she was at everything. She always thought of something super specific. Instead of just a train whistle, it was the train whistle from the lullaby that Mom would sing us. And she added her own category, too—in addition to a person, place, or thing, you could also think of a feeling. Her feeling wouldn’t just be something like “excited.” It would be the exact feeling of waking up on your birthday.

“I’m thinking of a feeling right now,” I said to Mom.

“A feeling that’s more happy or more sad?” Mom asked.

“More sad,” I said.

Mom asked a few more questions, but in the end she didn’t guess, so I had to tell her that the feeling was missing her.

And of course, after all of that, she told Aunt Amy to let me go.

Hannah’s house is outside of town, in the red dirt hills. Natalie’s mom dropped me and Natalie off, and Hannah brought us upstairs to say hi to her grandpa. When she knocked on his bedroom door, he came out to the hallway. He smiled at us, but Hannah had to yell when she told him my name, because he doesn’t hear very well. Her grandma was sleeping, and after we met him, her grandpa went back into his room to watch TV.

Then we went wandering in the forest behind the house, and Natalie and Hannah smoked cigarettes. You can walk to the river through the cottonwood trees covered in brambles and webs. The leaves have all turned yellow now, so the light looks golden even when the sun just leaks through the clouds. But when we started to get close to the sound of the river, it made me start to breathe too fast. I saw May that night in a flash, before my brain shut off and wanted to blank out. So while Natalie and Hannah walked to the riverbank, I hung back, pretending to get lost in looking at a spiderweb or something.

When we got back from our walk, we went to visit Hannah’s horse named Buddy. Buddy was actually her grandma’s horse, but since her grandma isn’t doing well, Hannah takes care of him, and she says Buddy is more like hers now. She says that Buddy is her favorite one in the family. She also takes care of Earl, their donkey, since she doesn’t trust her brother to be nice to the animals. To tell the truth, Hannah’s brother, Jason, is scary. He’s trying to train himself for the Marines, so he goes on obstacle courses he made for himself near the river, with old tires and ropes and things. He used to be a football player, but then he tore his shoulder, and he hasn’t been able to play since. He should have gone to college this year, but he didn’t. I don’t know if it’s because he couldn’t get in now that he can’t play football or because their grandparents are old and can’t really watch after Hannah. I think her brother thinks he’s supposed to be like her parent, but he’s bad at it. For groceries he only buys Vienna sausages in a can and grocery store–brand sour cream and onion chips. Even though their family isn’t poor or anything, maybe part of why Hannah wants to have a job is so that she can pick her own things to eat, without having to ask Jason. She likes to eat spinach out of the bag and Doritos (the real brand) and Luna Bars.

When Jason went for one of his workouts, which Hannah says take at least a couple hours, we decided to take Hannah’s grandma’s old van and practice driving. Natalie and Hannah both turned fifteen at the beginning of the year and have their learner’s permits. Natalie went first. She rolled the van down the dirt road, and Hannah stood up and stuck her head out of the sunroof and screamed, “Woohoo!” which I guess made Natalie want to go faster, so she did. The thing is, she went off the road when she swerved to miss a bird. Probably the bird would have flown away at the last minute, but I guess Natalie got nervous. So the car wheels stuck in the soft sand. Natalie revved the gas harder, but the wheels just spun farther into the ground.

Hannah kept saying, “We have to get it out. My brother can’t know.” She sounded terrified. She yelled for Natalie to push the gas harder, and Natalie was all shaky because Hannah was so upset, and then Hannah made Natalie and me get out, and she went behind the wheel and tried to make the car go herself. Natalie and I pushed from outside, but it wouldn’t move. It wouldn’t move at all. Hannah started crying, and she yelled at Natalie, “Why did you do that? Are you stupid?” Natalie’s cheeks and her chest turned red. I know it’s because she was trying not to cry, too. Eventually there was nothing to do but to walk back and tell Jason, who by now would be done with his workout.

Hannah told us to wait outside when she went into the kitchen. But we followed her and watched from the hallway. Jason wasn’t just angry. He was really, truly mad. His face was red, and he was screaming. He called Hannah a lot of bad names. I’ve never seen Hannah like that before. She laughs at everything and does whatever she wants, like she’s not afraid of anything. Like nothing can hurt her. But this was different. She was crying and she kept saying, “Please, Jason.”

I kept trying to think of a way to protect her, but I was scared frozen. Natalie must have felt the same. She kept whispering that she hated him, and that she wished she could punch him in the face, and those kinds of things. Finally Natalie went into the kitchen and stood next to Hannah. Hannah looked at her like she wished she would disappear. But Natalie said, in a very soft voice, “Please don’t get mad at her, it was my fault.”

Jason glared, but his voice got a little calmer as he said, “Like hell it was. That’s her dying grandmother’s car.” Then he threw his drink across the counter and he told Hannah, “Clean it up,” and he walked out. I guess he went to go get the car out with the tractor hitch.

We didn’t feel like staying in the house anymore after that, so what we did is we stayed in the barn that night. We got supplies while Jason was gone—flashlights and sleeping bags and Doritos and a bottle of this red wine that we took from her grandparents’ cabinet, because Hannah said that it had been there for years. It tasted old, like shoe leather and fall leaves and dusty apples. Hannah sang songs, Patsy Cline and Reba McEntire and Amy Winehouse. Natalie and I closed our eyes and listened. Sometimes Natalie sang along. When we were falling asleep in the loft, I heard Natalie whisper, “I’m sorry.” And she held Hannah, I think, all night. The hay in the barn smelled sweet, as if it were still growing in the rain.

I understood then, at least a little bit, why Hannah always has a boyfriend or sometimes more than one. I think she needs people to love her and give her attention. Her grandparents don’t seem like they can be there for her, and her brother is terrible to her. I want her to see that Natalie could love her for real. I think that deep down, Hannah must know that, but I’m not sure if she can imagine what it would be like. Maybe part of her would rather have Natalie as a best friend, because best friends don’t break up or anything like that. And even though it shouldn’t be this way, a relationship like theirs still makes you different in some people’s minds. Maybe Hannah isn’t ready yet to stand up for it. Because once you’re afraid of one thing, you can get scared of a lot of stuff. In school, the teachers tell Hannah, “Don’t waste your talent.” But she doesn’t turn in her papers or anything. She acts annoyed that they care about her, like she doesn’t trust it. Even if she can laugh at everything and have as many boyfriends as she wants, I think Hannah must be afraid like I get afraid, the way I did when I heard the river yesterday, the way I do when I don’t even know what the shadow is, but I feel it breathing.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear Amelia,

I have to tell you about Halloween. My costume was a big hit! Everyone at the party truly loved it. I explained to all of them that I wasn’t dead, only somewhere still circling in the air.

Natalie was Vincent van Gogh, which meant she taped a bandage over her ear to make it look like it was cut off and splattered paint all over her clothes. Hannah was Little Bo Peep, which meant she braided her hair in pigtails and wore a tight blue dress. Hannah’s boyfriend, Kasey, was a sheep, because she made the costume for him. He looked pretty funny with his little fuzzy cotton ears and his neck and shoulders that are so big they blend into each other. When we walked in tonight, to the house that he shares with four other guys, Hannah jumped on him, and he picked her up. He called Hannah “Jailbait” as a nickname, like “How’s my little Jailbait?” which made his friends laugh. Hannah laughed, too, although Natalie did not.

Some other people at the party dressed up as characters from Candy Land—Queen Frostine, Princess Lolly, and Lord Licorice. I thought this was the coolest. Kasey and his friends knew how to throw a party right. Even though their house is pretty dirty, it wasn’t just the typical college guy party with a keg of beer. For Halloween, they’d made it special. There were bowls of M&M’s everywhere, and hot chocolate that was spiked. I kept looking around for Sky, wondering if he’d come, wondering if one of the people behind the masks across the room was him, but when I checked the way they walked, none of them were right. I decided I needed to distract myself from looking for him, so I went bobbing for apples. May and I used to fill up a washtub and put apples in it and practice, any time of year. I was always great at it, even when I still had my baby teeth.

I started bobbing, and the boy dressed as Lord Licorice bobbed down next to me. The top of his feathered hat kept bumping my aviator cap. And sometimes, when we’d look up at the same time, his dark eyes seemed like they were trying to make holes in me. I would let them burn until the holes got too deep, and then I’d put my head down again. When I finally got an apple and came up triumphantly, Lord Licorice was still bobbing, and I saw Sky standing there, right above me. I had the apple in my mouth when he said hi.

Normally I would have felt embarrassed or maybe guilty that I was bobbing for apples next to Lord Licorice, but I was feeling very brave dressed as you, and very cool. So I put down my pilot glasses as I took a bite out of the apple in my mouth.

I said, “Let’s go flying.” I guess at that point I might have been a little bit drunk, too.

Sky said, “The ceiling might get in our way.”

So I took his hand and pulled him out the front door. And then I started running. Sky stopped following near the edge of the yard, but I ran down the street with my arms out like wings, laughing. I didn’t care. I was happy. By the time I got to the end of the block and onto the next one, I was above the earth. I could see the treetops, I swear. I could see the streets crisscrossing. The houses were like toys, and pretty soon the whole earth had become a map.

When I finally landed, Sky was standing there, waiting for me at the edge of the yard, which just a moment ago was only a tiny square. I forgot to mention that Sky was dressed as a zombie rocker, which just meant he looked cool in his leather jacket, like he usually does, and had drawn some crisscrosses on his face with what looked like black marker.

“How was the flight?” he asked.

“You should have come,” I said, out of breath. “I almost made it around the world.”

“Who was that pirate boy in there?”

“He wasn’t a pirate, he was Lord Licorice. Didn’t you ever play Candy Land?”

“It looked like he thought you were the candy.” His voice sounded disapproving, in a way that I liked. It meant that he was protective of me, or maybe that he wanted me to himself.

I could feel myself blush, and I hoped he couldn’t see in the dark. I fidgeted with my aviator cap. “We were just bobbing for apples.” I put my aviator glasses on over my eyes. “Anyway, you’re the one who doesn’t want to be my boyfriend.”

“How do you know?”

I shrugged. “You’re not like that.”

“What if you’re wrong? What if I am?”

“You are?”

There was a moment of quiet. “Well, I am now.”

“So am I,” I said softly, and I fell into him so he’d catch me, a swoony kind of fall where you don’t hold your body up, and I laughed. He lifted the glasses back off my face, and we kissed, and I felt his cold hands slip under my shirt, onto my stomach. I felt his hands warmer on my back, and I felt his lips on my neck, and I felt like I’d landed in my body for the first time. Against his hands, it was something new to me. Sky made me feel clean, a first-snow kind of clean that covered everything. I remembered how it was being above the trees, which were making a good sound, a rustling sound, a leaves-turned-brown-and-ready-to-fall sound. “Listen,” I said.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear River Phoenix,

Maybe this is weird to say, but when I was younger, before I’d ever kissed, sometimes I’d imagine kissing you. Now that I kiss in real life, I’m happy to say that it’s a lot like I’d hoped it would be.

My boyfriend, Sky—my first boyfriend—he is perfect to me. It’s been two weeks since the Halloween party where we got together. And now, we’ve gotten to kissing everywhere. Kissing in the alleyway between classes, when no one is there, and the sun makes spots in the bright middle of my eyelids. Kissing in his truck that smells like thousand-year-old leather. Kissing when it’s dark and I crawl out of my window. (I’ve gotten good at it at both houses. At Aunt Amy’s my window pushes up, but at Dad’s I have to unhook my screen, the way that I used to see May do.) I love these middle-of-the-nights with Sky the best. Everything else is sleeping, and the whole world feels like our secret. It reminds me of the feeling I used to get when May and I would sneak into the yard to collect ingredients for fairy spells.

For the first time in forever, it feels like I have magical powers—the ones that May taught me about when we were little. With Sky, I can make the scary stuff disappear. We walk through the neighborhood after dark, and our shadows stand on top of each other, stretching across the whole street. We kiss, and I feel that if my shadow could stay inside of his, then he could eclipse everything that I don’t want to remember. I can get lost in the things about him that are beautiful.

Sky reminds me of you a bit, honestly. How he’s a boy, and strong, and the air makes way for him when he walks through it. But also how there is something fragile like moths inside of him, something fluttering. Something trying desperately to crowd toward a light. May was a real moon who everyone flocked to. But even if I am only Sky’s street lamp, I don’t mind. It’s enough to be what he moves toward. I love to feel the wings beat.

Last night we walked to the park, and we kissed with my back pressed up against the cold bars of the jungle gym. We stopped for breath, and his bottom lip fell a little crooked to the left, like it does. I whispered, “Can we go to your house?”

He sounded uncertain. “I don’t know if that’s a good idea.”

“We don’t have to go in. I just want to see it.” I didn’t tell him that I already had, the night that I drove by with Tristan and Kristen at two a.m. I wanted to be there with him.

“I don’t think you understand,” he said finally. “My mom isn’t really … like other moms.”

“How do you mean?”

On the outside, Sky got tougher. “She just has her own way of doing things.” Then he said, “Like, she sings lullabies to the flowers in the middle of the night.”

“Oh. Well, that’s okay.”

“They’re dead now,” Sky added. “Her marigolds are. She sings to them anyway.”

“Maybe we could plant some bulbs for her. Tulips, or something that will grow in the spring.”

Sky wasn’t so sure about it, but I promised him we could just stay in the front yard and we wouldn’t have to go inside, and he finally agreed. So tonight, I snuck out again to meet him, and we drove to his house to pull up the dried-out marigolds and put in tulip bulbs. Earlier today I’d gone into our shed, where Mom used to keep her gardening stuff, and found some stacked in a box with newspaper between them. It was a new moon night, and we worked in the dark, wearing our jackets. As we were patting down the last ones, our nails with dirt under them, we looked up at each other, and our eyes touched, closer than you can get even with skin.

That’s when the front door opened. It was his mother, standing there in her bathrobe, holding a watering can.

“Mom?” Sky asked wearily. “What are you doing?” I think he’d been hoping that she would stay asleep and he wouldn’t have to introduce us yet.

“I wanted to help,” she said innocently.

Then she turned to me and looked me in the face, as if she’d just noticed that I was there. Her expression was warm. “And who is this?” she asked Sky.

“This is Laurel,” Sky said.

“We, um, we planted tulip bulbs,” I said, “so they’ll grow in the spring.”

Sky’s mom smiled and nodded, as if planting flowers in the middle of the night were normal. “Thank you, dear.”

She started to walk up and down the rows, sprinkling the dirt. She sang softly as she went, something about horses in the sun.

“It’s important to sing to them,” she said when she was done. “So that they know you are there.” Then she took her watering can and set it near the front door and just walked back inside.

“So that was my mom,” Sky said.

“She … she seems really nice.”

“You mean crazy.”

“Well, no. But what’s, um, what—”

Sky’s voice turned hard. “That’s just the way she is.”

“Oh.”

I reached out and put my arms around his body. It was then that I could feel that the moths in him, with their wings so paper-thin, will never be near enough to the light. They will always want to be nearer—to be inside of it. It was then that I could feel the lost thing in him. I wanted to put my hand on his chest, against his heart, and touch all the way inside his beating. I wanted to find him. But he stepped back, and his bottom lip, crooked just a little to the left, straightened out.

I felt like there were a million questions and answers and questions all stuck in the back of my throat. But I couldn’t speak from everything being stuck there. I stopped.

“Sky?”

“What?”

I looked at him. And I meant everything. “Nothing,” I said, and then I paused. “Those flowers are going to be really pretty.” The cold night sent a shiver up my spine, and we kissed again.

Yours,

Laurel

Dear John Keats,

Today we got our report cards from first quarter. I had all As, except in two classes. In PE, I had a C-, not because I can’t run fast, but because Hannah and I pretended to forget our gym clothes so many times. And in English I had a B, even though I’ve gotten As on all of my essays. The reason for this is that I don’t talk in class, because I hate the way Mrs. Buster looks at me, so my participation grade was low. And also that I had a missing assignment—a letter to a dead person. It’s one little assignment, and I wish I had just made myself fake it, but I couldn’t. I mean, my letters are actual letters to the people I am writing to. Not to Mrs. Buster. But there is one way to make Dad happy, and also for Aunt Amy to feel sure that I am free of sin, and that’s to get all As. I tried to make sure that my grades were good so that no one would have any reason to worry or ask questions. I hope this is close enough.

Mrs. Buster called me over to her desk after class today and asked why I hadn’t done the letter assignment, even after she gave me two extensions. She said I should be an A student. And I tried to explain that I did do it, I just couldn’t show her. But she said the point of an assignment is to turn it in. I tried to explain that I thought that letters were actually very private.

She looked at me funny. Then she said, “Laurel, you are a very talented girl,” but she said it like it was not a good thing.

I shrugged.

Then she said, “I notice that you don’t speak up in class much.”

I haven’t really talked at all, actually, since the second week of class when I said something about Elizabeth Bishop. I just pass notes now with Natalie, or look out the window. I pay attention only when we are reading poems.

I shrugged again.

“Laurel, I just want to encourage you…” She paused, like she wasn’t quite sure what she wanted to encourage me to do.

Then she said, “May was special, too, like you.”

I almost smiled at her. She said that I was like May.

But her big bug eyes started bugging out at me, like what she saw when she saw us was a tragedy. “I just don’t want you to waste your talent.” She paused again. “I don’t want you to go down the same road that May did.”

And then I was so angry that everything in my body clenched together. I didn’t know what “road” she thought May went down, or if she was trying to say that’s why she died. She wouldn’t know. No one did. She wasn’t there. No one was, no one but me. I was so angry that if my throat hadn’t been clenched too tight, I might have screamed at her. If she felt so bad about it and all, why didn’t she just give me an A? Grownups can be such fakes, I thought. They are always acting like they are trying to help you, and like they want to take care of you, but really they just want something from you. I wondered what exactly Mrs. Buster wanted. Finally I just nodded and forced myself to mumble something about I’m fine, just that one assignment was really hard.

The thing is, I can’t hate Mrs. Buster entirely, because she gives us things like your poems to read. Yesterday we read “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The poem is about an ancient urn with pictures on it. It sounds like it would be boring, but really it’s not. I like this part, where you are talking about two lovers, trapped in the instant just before they kiss:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

The boy and the girl beneath the trees, they will forever be frozen into exactly what they are just then—they will never touch lips, but they will never lose each other, either. They will be full of possibility, immune to whatever sorrow might follow.

It’s like that, almost, when you look at any picture. Like this picture framed on my desk in my room, of May and me as kids in our yard in the summertime. We are swinging on the swing set. I’m just starting to pump, still near the ground, watching her. She’s high up, right in the moment before she jumps. But she’ll never fall off. It’s just after sunset, so the air is still warm. We will stay where the sky is deep electric blue, never turning to night—a place beyond time that can’t be touched. When I sit at my desk and see the November sky purring with snow, it doesn’t matter. I am seven years old in the summer dusk.

But what I love most is the end of your poem, when the urn talks to us. It says this: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” I keep trying to figure out exactly what you mean, but that sentence is like a circle. If beauty is truth, and if truth is beauty, they are defined by each other, so how do we know the meaning of either? I think that we make our own meanings, by putting ourselves into them. I put the moon over the street lamp into the idea of beauty, and I put the feeling of Sky’s heartbeat like moths wings, and I put Hannah’s singing voice, and I put the sound of my footsteps running after May along the trail by the river, chasing the sky. And then I start to circle back to the idea of truth. I put how May said her first memory was of holding me after I was born, and how she said she was proud when Mom trusted her to take me in her arms. I put the way Sky’s voice sounded when he said he wanted to be a writer, and that he’d never told anyone before. I put Natalie holding Hannah the night we slept in the barn. And I put when May whispered in my ear, “The universe is bigger than anything that can fit into your mind.”