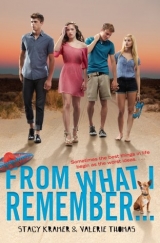

Текст книги "From What I Remember"

Автор книги: Valerie Thomas

Соавторы: Stacy Kramer

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

hat was wack, bro,” Charlie says. “Girl’s a freak!” I say to Charlie. But what I don’t tell Charlie is that Kylie is right. I can be an asshole. It’s a role I’m pretty comfortable with. Bottom line, I get away with a lot of shit around here ’cause people let me. The thing is, everyone’s always wanting something from me. If I worried about everyone’s feelings, I’d never get anything done. I’ve got to take care of myself. I can’t be dealing with everybody’s junk all day long. And Murphy’s assignment is definitely Kylie’s junk. I should put it out of my head. Normally I would. But I made a promise to myself when my dad went into the hospital for the second time, that I would stop being such a selfish prick, because maybe that isn’t the way to go through life. It didn’t work out so well for my dad.

hat was wack, bro,” Charlie says. “Girl’s a freak!” I say to Charlie. But what I don’t tell Charlie is that Kylie is right. I can be an asshole. It’s a role I’m pretty comfortable with. Bottom line, I get away with a lot of shit around here ’cause people let me. The thing is, everyone’s always wanting something from me. If I worried about everyone’s feelings, I’d never get anything done. I’ve got to take care of myself. I can’t be dealing with everybody’s junk all day long. And Murphy’s assignment is definitely Kylie’s junk. I should put it out of my head. Normally I would. But I made a promise to myself when my dad went into the hospital for the second time, that I would stop being such a selfish prick, because maybe that isn’t the way to go through life. It didn’t work out so well for my dad.

“She kicked me. Hard. Chick has issues,” Charlie insists.

“Totally,” I say. But I can’t help feeling sorry for Kylie. She takes everything so goddamned seriously. No one wants to hang with her, except for weird Will Bixby. I mean, who gets that worked up over an assignment? I can’t remember ever giving that much of a crap about any homework. Ever.

Charlie gets another point off of me. He’s in the lead. It’s eight to seven. Kylie totally messed with my head. I don’t need that kind of distraction, with tryouts for UCLA coming up next week. That’s a whole lot more important than some stupid paper for Murphy.

“Get your head in the game,” Charlie says.

“I’m trying,” I say. But it’s easier said than done. Charlie serves and I miss. Twice. It’s not even a good serve. It bounces off the back wall and stays high. I could have easily scooped in and slammed it. Instead, I’m wasting brain space on Kylie.

I jump up and down a few times. Shake my head. Okay. Moving on.

Charlie serves. I rush in, power driving the ball down the line. Charlie dives for it. Misses. My serve. I slam the ball. It hits the back, then the side wall, and dies on the floor. Ace. An impossible return. There’s nothing Charlie can do but appreciate my mad skills. I’m back. Kylie Flores is gone.

opefully, Kylie is getting on the 3:13 right now at the corner of Buchwald and Center. Otherwise, she’s going to be late, and Mom will be mad. The bus will stop fourteen times before she gets off. The ride is fifty-two minutes long. Unless the bus hits all the green lights; then the ride is forty-one minutes. But this only happens five times a year. Just like me, Kylie likes to sit by the window and look out as the bus cruises toward Logan Heights. There are 186 buildings downtown. More than twenty-nine of them stand taller than three hundred feet. The tallest building in the city is thirty-four stories. One America Plaza. It may not sound very tall if you’ve been to Chicago or New York. I haven’t. So One America Plaza seems really tall to me.

opefully, Kylie is getting on the 3:13 right now at the corner of Buchwald and Center. Otherwise, she’s going to be late, and Mom will be mad. The bus will stop fourteen times before she gets off. The ride is fifty-two minutes long. Unless the bus hits all the green lights; then the ride is forty-one minutes. But this only happens five times a year. Just like me, Kylie likes to sit by the window and look out as the bus cruises toward Logan Heights. There are 186 buildings downtown. More than twenty-nine of them stand taller than three hundred feet. The tallest building in the city is thirty-four stories. One America Plaza. It may not sound very tall if you’ve been to Chicago or New York. I haven’t. So One America Plaza seems really tall to me.

Kylie puts in her earbuds and listens to music so she doesn’t have to talk to anyone. I like to talk to people when I’m on the bus. Sometimes they get up and change seats. Mom says not to be upset, people just don’t like to talk to strangers. Lately, I’ve tried not to talk as much. But when Mom or Kylie aren’t in the mood to talk, it’s hard to know what to do with all the words. There’s always something interesting to talk about, like why certain cacti lean way over but don’t fall to the ground (I suspect this has to do with the moisture content in the cactus fiber), or how the labels on most soda bottles are exactly the same size as the labels on ketchup bottles, almost all of which are manufactured in Malaysia.

I wish I were on the bus right now with Kylie. She always likes listening to me. We could talk about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch that I read about in school today.

I hear a key in the lock. Kylie’s home.

ctober 1972,” I say to Jake as I enter the house and see him waiting for me on the maroon chair next to the couch, a bowl of carrots on his lap. I hang up my backpack and step over the enormous pile of laundry deposited at the bottom of the stairs, wondering if it’s clean or dirty. Jake smiles at me like it’s been ten years since we’ve seen each other. Still, it’s nice to be greeted every single day with such enthusiasm. Even if Jake’s brain is a little scrambled from Asperger’s, it feels good to be loved this much. There aren’t a lot of people who feel so positively inclined toward me. “Hurricane Dimitri,” he yells out triumphantly. “Seven people died in Galveston, Texas, and there was twelve inches of precipitation over two days.” Jake eyes shine with excitement.

ctober 1972,” I say to Jake as I enter the house and see him waiting for me on the maroon chair next to the couch, a bowl of carrots on his lap. I hang up my backpack and step over the enormous pile of laundry deposited at the bottom of the stairs, wondering if it’s clean or dirty. Jake smiles at me like it’s been ten years since we’ve seen each other. Still, it’s nice to be greeted every single day with such enthusiasm. Even if Jake’s brain is a little scrambled from Asperger’s, it feels good to be loved this much. There aren’t a lot of people who feel so positively inclined toward me. “Hurricane Dimitri,” he yells out triumphantly. “Seven people died in Galveston, Texas, and there was twelve inches of precipitation over two days.” Jake eyes shine with excitement.

“Okay…December 1956.”

“Hurricane Meredith. Jamaica lost power for six days. Winds up to 146 miles an hour.” Jake jumps up. His carrots spill across the floor. At thirteen, he’s my height, his jagged energy bouncing off him like electric currents. On the heels of my enormously bad day, I am feeling irritated by Jake, which I try to hide.

“Pick up the carrots, Jakie,” I say.

Jake scowls at me. “No. I won’t.”

I soften my tone. “Please pick up the carrots. And then we’ll keep playing.” I wrap my arms around his hulking frame and pull him close. “Did you have a good day?”

“Yeah. We learned about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” Jake responds, eager to tell me more.

I smile. No matter how bad my day is, Jake can always make me smile. His passion for minutiae is infectious. Until it gets annoying.

“Did you have a good day, Kylie?” Jake asks. He’s been learning about manners and empathy at school, things that don’t come naturally to him. It seems like it’s finally sinking in. Jake is usually so immersed in his own world, he forgets to ask me about mine. Not that I mind. It’s a relief to spend some time in someone else’s reality.

“My day was great,” I lie. I know the truth will only confuse and depress him, just as it does me. He has a limited capacity to understand complicated social interactions, and my life is chock-full of them.

“Me too.” Jake smiles, genuinely pleased. “I like when we both have good days.”

I point to the carrots on the floor. “How about those carrots?”

Jake reluctantly gets down on all fours and gathers up a few carrots. He flicks one under the couch, for fun. He watches to see what I’ll do. I pretend not to see. I’m too wiped to care.

Jake stands up and looks at me expectantly.

“Okay. November 1932,” I say.

“There was no hurricane that month. Just a tropical storm. That’s boring.” Jake peers at me, eager. Too eager. “Give me another one.”

Just once, I’d love to come home, disappear into my room, listen to some Arcade Fire, and spend some quality time writing.

“Okay, here’s a reverse one. Hurricane Dana,” I say.

“Oooh. I know that one.” Jake is so excited, he starts to vibrate.

Jake is smart. Scary smart. People assume he’s stupid because he’s got a disability, but they’re dead wrong. If anything, he’s disabled by his superbrain. The carrots are back on the floor.

Mom rushes down the stairs, her uniform hanging open, her overstuffed purse dangling from her arm. “Can you make dinner, Kyles?”

She kneels down and picks up the carrots.

“Mom, please don’t do that. Jake can pick them up. Right, Jake?”

Jake says nothing.

Mom continues to gather the carrots into the bowl with one hand as she buttons her uniform with the other. “Oh, Kylie, it’s just carrots. Don’t be so hard on him.”

Jake looks at me, and we have a moment of understanding. He’s gotten away with it, as usual.

“Here, honey.” Mom hands me a piece of paper with an elaborate chart sketched on it. “He’s got to do three sets of fifteen each, okay, and that includes the arm stretches and the hopping thing the doctor showed us the other day. He needs it to improve his balance. And don’t forget the pills.” If Mom paid one tenth this much attention to me, maybe I wouldn’t have lost my mind on a squash court this afternoon.

“Okay,” I say.

“I want to play guitar tonight. I don’t want to do the stupid exercises.” Jake’s mood is shifting.

“You can play guitar, honey, after you and Kylie do the exercises, and after you eat dinner. Kylie, I left some salad in the fridge, but you can make some pasta or something. And Dad should be home in a half hour. He came back a day early.”

Mom works as a nurse at Piedmont Retirement Village four nights a week. I’m in charge of myself and Jake those nights. And Dad, whenever he’s around. God knows what will happen once I leave. Dad doesn’t spend a whole lot of time taking care of anyone but himself. He mows the lawn and takes out the garbage, such classic dad duties it would be funny if it weren’t slightly tragic.

“And can you do the laundry, Kyles?”

“Is that clean or dirty?” I ask, pointing to the mound of clothes on the floor.

Mom stares at the pile, confused. “Can’t remember. Can you poke around and figure it out?”

“Sure,” I respond. What else can I say?

Mom pecks Jake on the cheek and then rushes out the door with a wave. “Bye, guys. Love you.”

I look at my watch. Mom’s going to be twenty minutes late to work. Typical.

This has been my life for as long as I can remember. Mom is so distracted by Jake, everything else is an afterthought and I’m forced to pick up the slack. Normally, I don’t complain. It’s pointless. It’s just, today I’m so not into sifting through a heap of potentially smelly clothes and then whipping up dinner for three. I comfort myself with the thought that I’ll be gone soon.

But that comfort is fleeting. As much as I want to escape, I worry about how Mom will handle things on her own. On the one hand, it makes me want to enroll at UCSD and just live at home. On the other, New York City doesn’t seem far enough away. The moon doesn’t seem far enough away.

I’m interrupted from my roundelay of anxieties by Jake tugging at my sleeve.

“Can I tell you the answer? Can I tell you? Can I tell you?” Jake has been waiting patiently, and now he’s bursting to answer the question I’ve long forgotten. Still, he’s made impressive progress at his new school. I am reminded what Jake is capable of when he sets his mind to it. A year ago, he never would have had the self-control to wait. “September 1987. Grenada had bad flooding. Grenada had bad flooding!!”

“You’re amazing, Jake,” I say. And I mean it.

Jake could do this for the next ten hours. He will do this for the rest of his life, actually. This, and recite every iteration of the dozens of bus schedules that service the greater San Diego area.

I wade through the laundry and realize, to my relief, that it’s clean. One less thing to do. I grab the clothes and start to head up to my room. “Jake, I’m going upstairs for a little bit. You want to watch TV? Or read your book?”

“I want to tell you about the Garbage Patch,” Jake whines. “You have to hear about the Garbage Patch. You just have to.…”

I can feel myself shutting down. I just want to proof my valedictorian speech one last time, and get back to my screenplay. But then I see Jake’s hands trembling. He’s verging on a tantrum. I look at his sweet, open face, pleading with me for more time. I plop onto the couch with the laundry.

“Tell me, Jakie,” I say.

I fold the laundry as Jake settles onto the floor.

“Well, it’s twice the size of Texas and located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It’s made up of plastic and other forms of debris, like fishing nets. Garbage from all over the world gets sucked in by an oceanic gyre, which is a huge system of rotating currents.” He speaks with the zeal of a true believer. It’s not so much the words I’m hearing, it’s more the cadence.

“It takes about five years for a piece of garbage from the west coast of North America to be carried into the gyre. So if I lie down on a raft tomorrow, I could get to the gyre by 2017. Nobody knows how long it’s been there, but it’s growing larger every day. At some point it might just fill up the ocean so that we are the island and it is the land. I don’t understand why someone doesn’t just clean it up.”

He makes a good point.

Two of Jake’s friends who also have Asperger’s, have the same lilting quality to their speech. When all three of them are together, it can sound like a spoken symphony. They say people with Asperger’s can’t understand basic human signals, the little things we all do that mean “I don’t understand” or “You are standing too close.” They are always bumping up against a world that confuses and thwarts them, and occasionally, this foreign planet and its people can be too much for them, and they can rage, as Jake does sometimes, when his brain erupts into flames. Pure pain and anguish shoot out of him in the form of a tantrum. Despite the fact that I’m the “normal” kid in the family, I understand Jake’s behavior only too well. I experience it myself, albeit in a muted form. Sometimes I wonder who the normal sibling is. I’m rarely ever as happy or comfortable with myself as Jake can be. I wish life were easier for both of us. It would be nice to slip through the world, smooth and slick as arrows whizzing through air, instead of always crashing into things.

As Jake buzzes on, my mind drifts back to the worry stream, and I find myself lost in the current again. How will Jake deal without me? What if he can’t find his blue sweatshirt, which happens at least twice a week? What if Jake spits on his teacher again, Mom can’t leave her shift, and Dad is traveling? That happened last year, and I skipped my math test to pick him up.

And, on the B side, what about me? Wouldn’t it be ironic if Jake was just fine when I left, and I turned out to be the basket case, all alone in New York City? Who will be excited to see me when I return to my dorm after a long day of clawing my way through the city? Who will comfort me? Who will I confide in, without Will and Jake around?

But if I stay, I’ll never leave. And then what?

This is the drain of being me. I can’t seem to find the joy, just the dilemmas. A Möbius strip of crazed thoughts loops through my brain on constant rotation. I’ve wanted to go to NYU forever. When I got in—with a full ride, no less—my parents weren’t the least bit pleased to hear the news. Especially in light of the fact that I’d gotten into Brown, Princeton, and the University of Pennsylvania the same week. Mom and Dad were dead set against NYU, which is pretty funny since they know nothing about it. Unlike all the other Freiburg parents, they weren’t really involved in my college applications. Still, they knew enough to be alarmed that I was turning down a scholarship to an Ivy League school. They begged me to go to Brown, where I got a substantial amount of money. They didn’t fight for Princeton or UPenn, because, frankly, we couldn’t have afforded it. New York City scares the shit out of them, despite the fact that neither has ever been there.

“Be premed. Or prelaw. Do something practical,” Mom pleaded.

She can’t understand why I want to write movies. Though she hasn’t come right out and said it, she doesn’t think I have a chance in hell of actually succeeding at it. As far as Mom and Dad are concerned, I might as well sell cotton candy at the circus. But I am like a dog with a bone. Sheer tenacity won out over their eventual fatigue.

The front door opens and Dad walks in. He’s carrying a huge box of medical supplies.

“Hey,” I say.

“Hey, guys. Kylie, want to help with this?”

I get up and help him with the box. Dad’s been trying to sell medical equipment lately. I say trying, because it’s not going very well. Even though people still get sick, nobody wants what he’s selling, which is some new sonogram machine that’s twice the price but ten times more exact.

“So, how’d it go?” I say.

“Not great. Better luck next week, hopefully.” Dad gives me a weak smile.

Dad used to sell electronics at Circuit City, until they went out of business. (Which is kind of weird, considering everyone at Freiburg seems to have a house full of the latest, greatest, shiniest electronics. Rumor has it Deborah Sneeden has a retractable flat screen television in every room in her house. I guess the Sneedens didn’t buy their electronics at Circuit City.)

“Dad, Dad, I learned to play ‘Sergeant Pepper’ on the guitar, wanna hear?” Jake has grabbed his guitar and is swinging it around manically.

“Whoa there, buddy, let’s put that down. Don’t want to break it.”

Jake ignores Dad and starts strumming the guitar. It’s not exactly music, but it’s something. I’m proud of the fact that Jake is trying hard. Who cares if he can hit the right chords?

“I’ll tell you what,” Dad says, preparing for his exit. “Let me relax for a bit, and then maybe we can have a concert. Okay?”

Jake keeps playing, but Dad is already en route to the garage to fiddle with one of his beloved motorcycles, none of which he even rides. He’s much more interested in his old bikes than his kids. He’ll come back into the house for an awkward dinner—made, served, and cleaned up by yours truly—and then settle onto the couch with a six-pack, and be lulled to sleep by the dull sounds of episodic television.

I get that his life sucks (having doors slammed in your face every day must be soul-crushing). I get that selling medical equipment may not have been his lifelong dream (not that I have a clue what he’d rather be doing, since he never talks about his past). But I’d be a lot more sympathetic if he were more pleasant on the rare occasions when he was home. And if he took the time to talk to me or Jake about…anything. Maybe it’s a chemical thing and he just needs some pharmaceuticals (not likely that will ever happen). Or maybe this is just the way Dad is drawn. Anyway, I’ve kind of given up trying to get to know him. I’m outta here. But Jake’s not. So as long as I’m in this house, I’ll fight the good fight for Jakie; not that I actually expect it to yield results.

I follow Dad out the back door.

“You know, Jake notices that you’re always disappearing into the garage. You could spend a little time with him every now and then.”

“Kylie, I do not want to have this conversation. I’ve had a long day.”

“It’s like you avoid him. How do you think that makes him feel?”

Dad turns around and looks at me.

“I don’t ignore him. I’m just tired. Working on the bikes helps me relax. I’ll come back in soon.”

Same old story. I’ve been hearing it for years.

I think Dad blames Jake for his unhappiness. Maybe if he had the perfect son, with whom he could play football or ride bikes, he wouldn’t be hiding away in the garage. Or maybe that’s not it at all. Maybe Dad’s just a complete jerk. I’m not sure. Neither option is particularly appealing. I’m holding out hope for the former, but as the years march on, I have to say, the latter is gaining ground.

“Whatever,” I say, turning and making my way back into the house.

“Kylie…” Dad calls out, feeling a tinge of remorse, I’m guessing. Maybe he is human.

I turn around. “Yeah?”

“I’ll come in in a half hour. And I’ll listen to Jake play. Tell him that, would you?” Dad looks sincere, like he wants to be a better man. I think it’s just an attempt to assuage his guilt.

“’Kay. Sure,” I say. What I don’t say is, I’ll believe it when I see it. Which is never.

Dad has cut himself off from the world. It occurs to me that I cut myself off from the world, too. I may have an inherited tendency, but I’m hoping I’ll outgrow it. Or I’ll learn to fight against it. The one time I saw a different side to my Dad was when my grandmother, my Dad’s mother, was alive. She would come over every Sunday for dinner and Dad would dote on her. He was warm and sweet with Nana in a way he seems incapable of with me or Jake.

I return to the living room, where Jake is now watching TV. I sit back down on the couch to fold the rest of the laundry. My cell begins buzzing like a cicada.

“Hello?”

“Kylie?”

“Yeah.”

“Hey, it’s Max.”

Max? Seriously? How bizarre. I say nothing, though I’m rolling my eyes.

“Kylie?”

“What?”

“Listen, about today. You were right. I, uh, shouldn’t have blown you off.”

I’m a cynical, cold little bitch a lot of the time, but as soon as it’s clear Max is apologizing, I feel a swift rush of warmth spread through my body, and my initial temptation is to forgive him immediately. What a wimp.

“Kylie? Did you hear me?”

“Uh, yeah. And, uh, I’m sorry about walking into your squash game and kicking Charlie. I got a little carried away.” Breaking no records here for verbal dexterity and imaginative retorts, I’m folding like a house of cards.

“Yeah.” Max laughs. “You were pretty worked up. Anyway, if the paper means that much to you, I’ll do it. Or, at least I’ll give you what you need so you can do it for me.”

Max is sorry, but not enough to refuse my idiotic offer to write both papers. It’s my own fault. Several moments of awkward silence go by.

Finally, I manage a weak, “Okay. Whatever.” Jesus, that was lamer than lame.

“How about we meet at Roland’s Coffee Shop down by the pier tomorrow morning?”

“Um, I don’t really know where that is. Can’t we just meet at Starbucks on Randle, at seven thirty?”

“Sure, my treat.”

“I can pay for my own coffee,” I shoot back. I’m so sick of everyone reminding me that I’m the scholarship student. “I already agreed to meet you once, and you didn’t show up. How do I know it won’t happen again?”

“I’ll be there. If I’m not, you can come find me in Shuman’s Calculus and beat the shit out of me.”

“Okay. Whatever.” I’ve got to stop saying that stupid word.

“See you there,” Max says, and then he’s gone.